Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(7):1381-1383

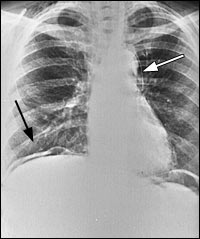

Four days after a routine colonoscopy for follow-up of Crohn's disease, a 40-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with severe abdominal pain, nausea, and a “noisy” neck. Right after the procedure she had developed abdominal pain and nausea that persisted after arriving home. She repeatedly vomited, and her symptoms progressed to include fever and chills, and gradual swelling of the neck and face. Her physical examination on arrival in the emergency department was remarkable for diffuse abdominal tenderness and a crunching sound audible in the neck region that coincided with her pulse. Her chest and abdominal radiographs are shown in Figures 1 through 3.

Question

Discussion

The answer is E: The presence of intestinal pathology, such as diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, colonic stricture, or previous abdominal surgery predisposes the colon to perforation during endoscopy. The incidence of perforation has been reported to range from 0.1 percent for flexible sigmoidoscopy, to 0.16 percent for diagnostic colonoscopies, and 0.44 percent for colonoscopy with lesion biopsy or resection.1 Most perforations occur in the rectosigmoid junction or the sigmoid colon.

Pneumomediastinum (Figure 1) may occur because of forceful vomiting with subsequent esophageal rupture (Boerhaave's syndrome), but it also may be caused by perforation of the colon with spread of intraperitoneal air through the peridiaphragmatic defect into the thorax. Colonic perforation can lead to air accumulation in a variety of places including subcutaneous emphysema, pneumatosis coli, pneumoscrotum, pneumopericardium, and pneumothorax.1

In patients with colon perforation, the clinical presentation is quite variable. The degree of complications depends on the size, site, and mechanism of perforation, as well as the underlying colonic pathology, degree of peritoneal contamination, and the condition of the patient.2 The most common symptom of perforation is abdominal pain. The onset of pain usually occurs during or soon after completion of the procedure, but it may be delayed or even nonexistent in some instances. In the most severe cases of perforation, spillage of bowel contents leads to peritonitis, sepsis, and circulatory collapse. Physicians should be alert for seemingly unrelated presenting complaints, such as shortness of breath or chest pain that may suggest pneumomediastinum. Subcutaneous emphysema can be diagnosed by the presence of crunching sounds coinciding with the heart rate, crepitus when palpating the overlying skin, or swelling of the face and neck.

Colon perforation with intraperitoneal air is usually easily detected on an upright chest film. In this case, a sickle-shaped collection of air is seen on the right side between the diaphragm and the dome of the liver (Figure 1, black arrow). It is best if the patient can stay in the upright position for five to 10 minutes before obtaining the radiograph. In this position, it is possible to detect as little as 1 to 2 mL of free air. For those patients who cannot maintain an erect position, a left lateral decubitus view of the abdomen may show the free air collecting between the lateral margin of the liver and the abdominal wall.

Figure 2 demonstrates a retroperitoneal perforation with air outlining the liver edge, right kidney(open arrow and short, black arrow), and the psoas muscle edge (long arrow). Pneumomediastinum can be diagnosed by demonstration of a thin, vertically oriented line of radiolucency, usually best seen along the left cardiac border and aortic knob (Figure 1, white arrow). A lateral chest radiograph may be particularly useful in detecting pneumopericardium, demonstrating the presence of retrosternal air (Figure 3).

Occasionally, plain radiographs may be normal in patients with colonic perforation and pneumoperitoneum. In such patients, air may be readily visualized by computed tomography (CT). A CT scan is extremely sensitive and is superior to upright chest radiography for detection of pneumoperitoneum.2

The management of colon perforation after colonoscopy is controversial. There are no randomized prospective studies available comparing expectant management to early surgical intervention. Typically, stable patients are managed conservatively with close clinical monitoring.3,4 The presence of subcutaneous emphysema, pneumoretroperitoneum, or pneumomediastinum after colonic perforation is not an absolute indication for surgery.4,5 Bowel rest, intravenous fluids, and intravenous antibiotics to cover enteric gram-negative and anaerobic organisms, with close observation for evidence of clinical deterioration are typical measures for conservative management.

A critical factor in the decision for expectant or surgical treatment is the quality of the bowel preparation at the time of the perforation. In general, a well-prepped bowel before endoscopy has a low risk of peritoneal contamination after perforation. Surgery is indicated in the presence of a large perforation with generalized peritonitis or evidence of developing sepsis. The patient was managed expectantly because she was in stable clinical condition, and she improved with conservative management.