Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(6):1057-1062

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

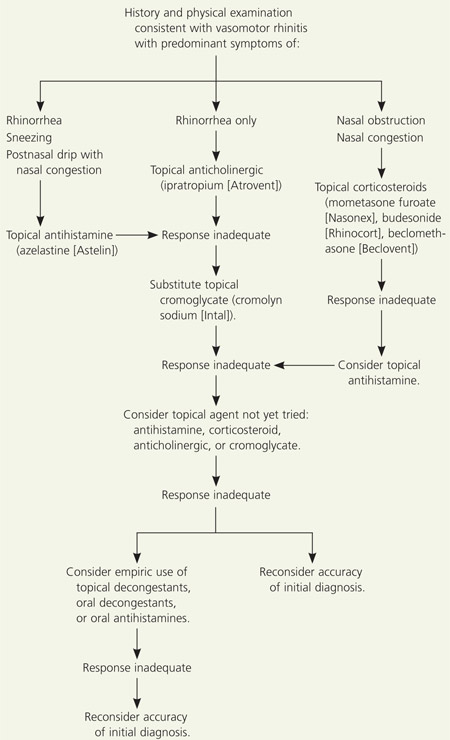

Vasomotor rhinitis affects millions of Americans and results in significant symptomatology. Characterized by a combination of symptoms that includes nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea, vasomotor rhinitis is a diagnosis of exclusion reached after taking a careful history, performing a physical examination, and, in select cases, testing the patient with known allergens. According to a 2002 evidence report published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), there is insufficient evidence to reliably differentiate between allergic and nonallergic rhinitis based on signs and symptoms alone. The minimum level of diagnostic testing needed to differentiate between the two types of rhinitis also has not been established. An algorithm is presented that is based on a targeted history and physical examination and a stepwise approach to management that reflects the AHRQ evidence report and U.S. Food and Drug Administration approvals. Specific approaches to the management of rhinitis in children, athletes, pregnant women, and older adults are discussed.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Topical anticholinergics should be used for rhinorrhea caused by vasomotor rhinitis. | A | 6,13 |

| Azelastine (Astelin) may be used for vasomotor rhinitis associated with rhinorrhea, sneezing, postnasal drip, and nasal congestion. | B | 6 |

| Topical corticosteroids may be used for vasomotor rhinitis associated with nasal obstruction and congestion. | B | 6,11 |

| Cromolyn sodium (Intal) may be used for vasomotor rhinitis associated with sneezing and congestion in patients older than two years. | B | 6 |

The classification of rhinitis has long been debated in the literature. Rhinitis is categorized as allergic or nonallergic, with vasomotor rhinitis in the nonallergic family.1 The symptoms of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis overlap significantly, but the causes appear to be entirely different.2 The major manifestations of allergic rhinitis are triggered by exposure to allergens and include nasal pruritus, clear rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, and nasal obstruction caused by inflammation of the nasal mucous membranes.3 Nonallergic rhinitis, a diagnosis of exclusion, can be sporadic or perennial.1 It includes a highly diverse group of rhinitis syndromes united by their pervasive symptoms of clear rhinorrhea or congestion with less prominent sneezing, nasal pruritus, and conjunctival irritation (Table 1).1

| Drug induced |

| Gustatory |

| Hormonal |

| Infectious |

| Nonallergic rhinitis with eosinophilia syndrome |

| Occupational |

| Vasomotor |

Vasomotor rhinitis is characterized by prominent symptoms of nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, and congestion. These symptoms are excessive at times and are exacerbated by certain odors (e.g., perfumes, cigarette smoke, paint fumes, inks); alcohol; spicy foods; emotions; and environmental factors such as temperature, barometric pressure changes, and bright lights.2 Patients with vasomotor rhinitis are further divided into two subgroups: “runners,” who demonstrate “wet” rhinorrhea; and “dry” patients, who exhibit nasal obstruction and airflow resistance with minimal rhinorrhea.1 Many studies have attempted to clarify the pathogenic mechanisms for these subgroups. Current theories include increased cholinergic glandular secretory activity (for runners), and nociceptive neurons with heightened sensitivity to usually innocent stimuli (for dry patients).1 These theories have not been adequately proven. The vasomotor nasal effects of emotion and sexual arousal also may be caused by autonomic stimulation. In one small study,4 researchers concluded that autonomic system dysfunction is significant in patients with vasomotor rhinitis (P < .005). Possible compounding factors included previous nasal trauma and extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease.4

Whatever their causal mechanisms, the various rhinitis syndromes result in significant morbidity in the United States. The National Rhinitis Classification Task Force concluded that 17 million Americans have nonallergic rhinitis.5 An evidence report6 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) estimated that 20 to 40 million Americans have allergic rhinitis, making it the sixth most prevalent chronic illness. Treatment costs are at least $1.8 billion annually for physician visits and medications, or nearly 4 percent of the $47 billion annual direct cost for treatment of respiratory illnesses in the United States.6 The total annual cost of allergic rhinitis in the mid-1990s, including lost productivity to employers and society, was $5.6 billion.6

The AHRQ found no prospective studies in the literature that explicitly differentiated allergic from nonallergic rhinitis. Making a specific diagnosis is most important if treatments vary between the conditions. Because of the crossover in treatments, differentiation is primarily significant when considering environmental control and institution of oral antihistamines and immunotherapy, which have proven benefit only in the treatment of allergic rhinitis.3 Because asthma and sinusitis are associated with allergic rhinitis, and a growing body of literature shows the increased effectiveness of intranasal steroids over oral antihistamines in the management of allergic rhinitis, it may be useful to establish a more specific diagnosis through diagnostic testing.3,6

Laboratory Testing

No specific test is available to diagnose vaso-motor rhinitis. In studies and in practice, allergic rhinitis is excluded or implicated as the cause of symptoms by using conventional skin testing or by evaluation for specific IgE antibodies to known allergens.7 According to the AHRQ,6 the results of “only one small recent study suggest that total serum IgE may be as useful as specific allergy skin prick tests, which, in turn, are more useful than radioallergosorbent testing in confirming a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis.”8 The lack of sensitivity and specificity of nasal cytology, total serum IgE, and peripheral blood eosinophil counts, which have been favored in the past for differentiating among rhinitis syndromes, makes their clinical use problematic.1 The minimum level of testing needed to confirm or exclude a diagnosis of vasomotor rhinitis has not been established in the literature.6

Management

| Medication class | Product | Effect | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topical antihistamines6,9,10 | Azelastine (Astelin) | Improvement in rhinorrhea, sneezing, postnasal drip, and nasal congestion9 | No serious or unexpected adverse events; bitter taste9 |

| Topical corticosteroids11 | Mometasone furoate (Nasonex) | Improvement in nasal obstruction and congestion scores11 | Epistaxis, nasal irritation11 |

| Topical corticosteroids6 | Budesonide (Rhinocort), beclomethasone (Beclovent), triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) | Improvement in nasal obstruction and congestion scores6,12 | Epistaxis, headache, nasal congestion |

| Topical cromoglycate6 | Cromolyn sodium (Intal) | Decrease in sneezing and congestion scores6 | Nasal irritation, headache, nasal congestion6 |

| Topical anticholinergics6,13 | Ipratropium (Atrovent) | Reduced rhinorrhea only6,13 | Minor adverse effects; nasal dryness and irritation13 |

| Other agents not recommended by AHRQ | |||

| Oral antihistamines | Sedating and nonsedating | AHRQ outcome not identified | Somnolence, dizziness, dry mouth, headache |

| Oral sympathomimetics | Only phenylpropanolamine (not available in the United States) was studied. | Withdrawn from the market; no other oral decongestant was identified or specifically studied. | |

| Leukotriene modifiers | Not identified in any trial on nonallergic rhinitis | ||

| Other agents not discussed by AHRQ: evidence for use lacking, empiric use possible | |||

| Topical decongestants | Oxymetazoline (Nezeril, Afrin, Dristan) | Improvement in congestion | |

| Oral decongestants | Pseudoephedrine | Improvement in congestion | |

Once a working diagnosis of vasomotor rhinitis has been made, the patient can be empowered to avoid known environmental triggers as much as possible. These may include odors (e.g., cigarette smoke, perfumes, bleach, formaldehyde, newspaper or other inks); auto emission fumes; light stimuli; temperature changes; and hot or spicy foods. A stepwise pharmacologic approach may then be employed, choosing the initial intervention based on the patient’s predominant symptoms. If the presenting symptom is solely rhinorrhea, a topical anticholinergic is the logical first step.6,14 With nasal congestion and obstruction only, topical corticosteroids would be a wise starting point for therapy.6 If the patient presents with the full range of symptoms including rhinorrhea with sneezing, postnasal drip, and congestion, a topical antihistamine may be initiated.6,9,10 After an adequate trial period, changes and additions may be made if the response is inadequate. Figure 1 describes a possible approach.

Exercise, beneficial for overall health, may be a useful treatment addition because it produces decreased airway resistance and assists natural nasal decongestion by I-adrenergic–mediated mechanisms.2 The effect of exercise on nasal decongestion is short-lived, but it has numerous other benefits and can be repeated.

Traditional oral antihistamines have no established beneficial effect in patients with vasomotor rhinitis and may be associated with sedation. Newer, less-sedating antihistamines also have no proven effectiveness for vasomotor rhinitis, and their administration delays proper treatment while incurring significant cost and burden to the health care system.3 According to the AHRQ report,6 there has been only one study regarding the use of oral antihistamines, and that study used an antihistamine-decongestant combination product, so the benefit of individual components could not be determined.15

The empiric use of the topical decongestant ephedrine on a chronic basis has resulted in tolerance and development of rhinitis medicamentosa. The inclusion of benzalkonium chloride as a preservative has been speculated to contribute to the development of these problems. In a small study16 of 35 patients, investigators examined the use of a newer agent, oxymetazoline, both with benzalkonium chloride preservative (Nezeril, Afrin No Drip 12 Hour, 4-Way 12-Hour, Dristan 12 Hour) and without. Results of this study16 demonstrated the short-term safety of the newer agent and the avoidance of rhinitis medicamentosa, with or without preservative, during use up to three times daily for 10 days.

Special Populations

CHILDREN

Preventive and nonpharmacologic approaches should be tried before beginning medication in children. Approved for use in patients six years and older, nasal anticholinergics such as ipratropium (Atrovent) often reduce rhinorrhea without the undesirable side effects of sedation and fatigue sometimes associated with oral antihistamine use.2,6 However, anticholinergics have no effect on the other symptoms of vasomotor rhinitis. Investigators conducted a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial13 in 204 children (six to 12 years of age) and adolescents (13 to 18 years of age) with allergic or nonallergic perennial rhinitis.

Patients with nonallergic perennial rhinitis who used ipratropium had a 41 percent mean decrease in severity and a 37 percent decrease in duration of rhinitis with excellent tolerability, compared with decreases of 15 and 17 percent in severity and duration, respectively, in the placebo group.13

Certain nasal corticosteroids, such as mometasone furoate (Nasonex), are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for children older than two years and improve the symptoms of congestion and nasal obstruction. Investigators conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 12-month study11 to monitor growth in children during treatment with mometasone furoate. A total of 82 patients, three to nine years of age, completed the study. There was no evidence of growth retardation or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression.11 Although short-term use studies purporting safety are quoted in the literature, budesonide (Rhinocort), beclomethasone (Beclovent), and triamcinolone acetonide (Kenalog) are not recommended for children younger than six years because of continued concern over possible long-term growth suppression by these older agents.12,17 Cromolyn sodium (Intal) can be used to manage symptoms of sneezing and congestion in children older than two years.6

As in adults, traditional oral antihistamines and newer less-sedating antihistamines have no established beneficial effects on vasomotor rhinitis in children. Prolonged use of topical nasal decongestants can cause irritation and rhinitis medicamentosa without proven benefit. If a therapeutic trial of one of these agents is attempted because of treatment failures with recommended agents, judicious and time-limited use should be considered.

ATHLETES

Topical antihistamines, topical corticosteroids, and topical anticholinergics are treatments permitted by the U.S. Olympic Committee and the International Olympic Committee. As of January 1, 2005, the World Anti-Doping Code no longer bans the use of pseudoephedrine, but systemic decongestants are included in the 2005 monitoring program.18 The code does not prohibit the use of topical decongestants. The stepwise approach to manage athletes should be the same as that used with other populations. A topical antihistamine (e.g., azelastine [Astelin]), topical corticosteroids (e.g., budesonide), and topical anti-cholinergics (e.g., ipratropium) may be tried. The 2005 World Anti-Doping Code requires an Abbreviated Therapeutic Use Exemption form to notify relevant agencies about the use of topical corticosteroids.19 Empiric short-term treatment with topical decongestants may be considered if these agents fail.

PREGNANT WOMEN

Symptoms of rhinitis can increase during pregnancy. This increase is thought to be caused by progesterone- and estrogen-induced glandular secretion, augmented by nasal vascular pooling from vasodilation and increased blood volume.20 Vasomotor rhinitis in pregnancy responds well to intranasal saline instillation.20 Potential risks versus benefits should be considered in the use of FDA-approved topical anticholinergics (pregnancy category B), topical antihistamines (pregnancy category C), and topical corticosteroids (pregnancy category C). Topical decongestants (pregnancy category C) can provide good short-term relief. Exercise appropriate for physical condition and gestational age also may reduce symptoms.1

OLDER ADULTS

Three types of nonallergic rhinitis commonly occur in older patients. The first, vasomotor rhinitis, is thought to be caused by increased cholinergic activity and is similar to that occurring in younger patients. The second type, gustatory rhinitis, is associated with profuse, watery rhinorrhea that may be exacerbated by eating. The third form is believed to arise from alpha-adrenergic hyperactivity, stimulated by the regular use of antihypertensives.2 All three types respond well to ipratropium nasal spray. Narrow-angle glaucoma is a relative contra-indication to the use of ipratropium.2

Prognosis and Additional Therapies

Although no single agent is uniformly effective in controlling the many and varied symptoms of vasomotor rhinitis, available evidence supports a stepwise application of several agents after a careful history and physical examination. Additional therapies, for which AHRQ felt there was no strong evidence base, may be tried if the approved approaches fail. These therapies include topical decongestants, oral decongestants, and local application of silver nitrate solutions by an otolaryngologist.21,22 Sphenopalatine blocks, also performed by otolaryngologists, are reserved for seriously affected patients who do not respond to other interventions and whose lives are altered significantly by their symptoms.23 The submucosal injection of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) has been studied in dog models24,25 and may yet prove to be of value.