Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(4):594-600

Patient information: See related handout on endometriosis.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Signs and symptoms of endometriosis are nonspecific, and an acceptably accurate noninvasive diagnostic test has yet to be reported. Serum markers do not provide adequate diagnostic accuracy. The preferred method for diagnosis of endometriosis is surgical visual inspection of pelvic organs with histologic confirmation. Such diagnosis requires an experienced surgeon because the varied appearance of the disease allows less-obvious lesions to be overlooked. Empiric use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen is a reasonable symptomatic treatment, but the effectiveness of these agents has not been well-studied. Oral contraceptive pills, medroxyprogesterone acetate, and intrauterine levonorgestrel are relatively effective for pain relief. Danazol and various gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues also are effective but may have significant side effects. There is limited evidence that surgical ablation of endometriotic deposits may decrease pain and increase fertility rates in women with endometriosis. Presacral neurectomy is particularly beneficial in women with midline pelvic pain. Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy definitively treat pain from endometriosis at 10 years in 90 percent of patients.

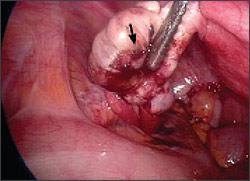

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence of endometrial tissue outside the endometrial cavity. These ectopic deposits of endometrium may be found in the ovaries, peritoneum, uterosacral ligaments, and pouch of Douglas (Figure 1). Rarely, extrapelvic deposits of endometrial tissue are found.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| The preferred method for diagnosing endometriosis is direct visualization of lesions with histologic confirmation. | C | 15 |

| Danazol (Danocrine) may be used for pain relief in patients with endometriosis. | A | 22 |

| OCPs, progesterone-only OCPs, and medroxyprogesterone acetate (Provera) should be used as first-line therapies for treating pain associated with endometriosis. | A | 24–26 |

| Because gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues provide equivalent pain relief as OCPs and progestogens with more side effects, they should be used only as second- or third-line agents. | A | 27 |

| Surgical ablation of endometrial deposits with or without laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation can be performed for pain relief. | B | 30,31 |

| Laparoscopic surgery can be performed in women with subfertility and endometriosis. | B | 32 |

| Presacral neurectomy can be performed in women with midline abdominal pain from endometriosis. | B | 31 |

| Laparoscopic cystectomy is preferred over drainage for pain relief in women with endometriosis. | B | 33 |

Morbidity rates associated with endometriosis are considerable. Between 1990 and 1998, endometriosis was the third most common gynecologic diagnosis listed in hospital discharge summaries of women 15 to 44 years of age.1 The prevalence of endometriosis in the general population is estimated to be 10 percent.2 A much higher prevalence of up to 82 percent occurs in women with pelvic pain, and in women undergoing investigation for infertility the prevalence is 21 percent.2–4 The prevalence in women undergoing sterilization is 3.7 to 6 percent.3,5

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Several theories have been suggested to explain the pathogenesis of endometriosis. The most widely held theory involves the retrograde reflux of menstrual tissue from the fallopian tubes during menstruation. Two other possibilities are the celomic metaplasia and embryonic rests theories. Celomic metaplasia hypothesizes that the mesothelium covering the ovaries invaginates into the ovaries, then undergoes metaplasia into endometrial tissue. The embryonic rests theory hypothesizes that Müllerian remnants in the rectovaginal region differentiate into endometrial tissue. A woman’s risk for endometriosis increases with increased exposure to endometrial material; thus, shorter menstrual cycles, longer bleeding, and early menarche are risk factors (Table 1).2,6–10 Being overweight and smoking have been associated with a lower risk of endometriosis.11

| Risk factor/comparison | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|

| Mother or sister has endometriosis/mother and sister do not have endometriosis | 7.2 | 2.1 to 24.36 |

| Menstrual flow six days or more/flow less than six days | 2.5 | 1.1 to 5.97 |

| Menstrual cycle less than 28 days/cycle of 28 to 34 days | 2.1 | 1.5 to 2.98 |

| Consuming one or more alcoholic drinks per week/no alcohol consumption | 1.8 | 1.0 to 3.29 |

| Never used OCPs/ever used OCPs | 1.6 | 1.2 to 2.210 |

| Use of pads and tampons/use of either pads or tampons | 1.4 | 0.9 to 2.02 |

Diagnosis

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Endometriosis usually becomes apparent in the reproductive years when the lesions are stimulated by ovarian hormones. Symptoms tend to be strongest premenstrually, subsiding after cessation of menses. Pelvic pain is the most common presenting symptom; other symptoms include back pain, dyspareunia, loin pain, dyschezia (i.e., pain on defecation), and pain with micturition. A patient survey of women in the United Kingdom and United States who were referred to university-based endometriosis centers found that 70 to 71 percent presented with pelvic pain, 71 to 76 percent with dysmenorrhea, 44 percent with dyspareunia, and 15 to 20 percent with infertility.12 In a British study of women with pelvic pain, many patients who eventually were diagnosed with endometriosis had been diagnosed previously with irritable bowel syndrome.13 Endometriosis is associated with infertility because of adhesions that distort the pelvic anatomy and cause impaired ovum release and pickup. However, tubal distortion is not the only cause of infertility, because patients with endometriosis seem to have poor ovarian reserve with low oocyte and embryo quality. A meta-analysis of 22 studies evaluating in vitro fertilization outcomes found that patients with endometriosis had a pregnancy rate of nearly one half that of patients without endometriosis, with decreases in fertilization, implantation, and oocyte production rates.14

SURGICAL PRESENTATION

The preferred method for the diagnosis of endometriosis is direct visualization of ectopic endometrial lesions (usually via laparoscopy) accompanied by histologic confirmation of the presence of at least two of the following features: hemosiderin-laden macrophages or endometrial epithelium, glands, or stroma.15 Diagnosis based solely on visual inspection requires a surgeon with experience in identifying the many possible appearances of endometrial lesions; nonetheless, there is relatively poor correlation between visual diagnosis and confirmed histology. For example, microscopic endometrial lesions may be found in normal-appearing peritoneal samples.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

| Dysmenorrhea | |

| Primary | |

| Secondary (e.g., adenomyosis, myomas, infection, cervical stenosis) | |

| Dyspareunia | |

| Diminished lubrication or vaginal expansion because of insufficient arousal | |

| Gastrointestinal causes (e.g., constipation, irritable bowel syndrome) | |

| Infection | |

| Musculoskeletal causes (e.g., pelvic relaxation, levator spasm) | |

| Pelvic vascular congestion | |

| Urinary causes (e.g., urethral syndrome, interstitial cystitis) | |

| Generalized pelvic pain | |

| Endometritis | |

| Neoplasms, benign or malignant | |

| Nongynecologic causes | |

| Ovarian torsion | |

| Pelvic adhesions | |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | |

| Sexual or physical abuse | |

| Infertility | |

| Anovulation | |

| Cervical factors (e.g., mucus, sperm, antibodies, stenosis) | |

| Luteal phase deficiency | |

| Male factor infertility | |

| Tubal disease or infection |

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

There are few well-studied clinical maneuvers for use in the diagnosis of endometriosis. Signs may be absent or may include tender nodules in the posterior vaginal fornix, uterine motion tenderness, a fixed and retroverted uterus, or tender adnexal masses resulting from endometriomas. One study determined the usefulness of clinical signs and symptoms in the diagnosis of endometriosis in women who present with infertility.17 Although no test provides strong evidence for the presence of endometriosis, the symptom of uterosacral pain has the highest positive likelihood ratio.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Two tests, serum cancer antigen 125 (CA 125) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), have been closely studied for endometriosis, but neither have shown impressive diagnostic accuracy. The use of MRI for diagnosis of an endometrial cyst is much more accurate than for endometriosis. Although there is a wealth of interest in the use of serum markers to diagnose endometriosis, none are accurate enough to be used in routine clinical practice. Elevation in levels of CA 125 (i.e., greater than 35 IU per mL), more commonly known for its use in the diagnosis or monitoring of ovarian cancer, is of limited diagnostic value; however, given its high specificity, CA 125 may be useful as a marker for disease monitoring and treatment follow-up. In addition, a well-designed meta-analysis found that measurement of serum CA 125 levels may be useful in identifying patients with infertility who may have severe endometriosis and could benefit from early surgical treatment.18

One report on the use of serum cancer antigen 19–9 (CA 19–9) in the diagnosis of endometriosis found that CA 19–9 has inferior sensitivity to CA 125 but may be of some use in determining disease severity.19 There is emerging interest in a variety of other markers. One relatively small study found that the cytokine interleukin-6 (at a cutoff value of 2 pg per mL) may be more sensitive and specific than CA 125.20 Measurement of tumor necrosis factor G in the peritoneal fluid also has shown diagnostic promise, with sensitivity and specificity of 1 and 0.89, respectively. However, this test requires an invasive procedure to obtain the fluid. It may prove useful as an adjunct to less-obvious surgical diagnosis.

Transvaginal ultrasonography has been proven useful in the diagnosis of retroperitoneal and uterosacral lesions, but it does not accurately identify peritoneal lesions or small endometriomas.21 Computed tomography (CT) has not been studied rigorously or promoted as a diagnostic imaging modality.

DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGY

There are no sufficiently sensitive and specific signs and symptoms or diagnostic tests for the clinical diagnosis of endometriosis, and no diagnostic strategy is supported by evidence of effectiveness. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends a pretreatment diagnostic strategy to exclude other causes of pelvic pain such as chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, fibroid tumors, and ovarian cysts.15 Nongynecologic causes of pain also should be excluded. Pelvic and rectal examinations should be performed, although the yield of the physical examination is low. Findings of a retroverted uterus, decreased uterine mobility, cervical motion tenderness, and tender uterosacral nodularity are suggestive of endometriosis when present, but these findings often are absent. Laboratory tests and radiologic examinations usually are not warranted. Measurement of CA 125 levels may be useful for monitoring disease progress, and MRI has a high sensitivity in detecting endometrial cysts but poor diagnostic accuracy for endometriosis in general. Empiric diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis is reasonable, based on clinical suspicion and presentation. Patients with persistent symptoms after empiric treatment should be referred for laparoscopy, the preferred method for diagnosis of endometriosis.

Treatment

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Standard medical therapies for patients with endometriosis include analgesics (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs] or acetaminophen), oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), androgenic agents (e.g., danazol [Danocrine]),22 progestogens (e.g., medroxyprogesterone acetate [Provera]), gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRHas; e.g., leuprolide [Lupron], goserelin [Zoladex], triptorelin [Trelstar Depot], nafarelin [Synarel]), and antiprogestogens (e.g., gestrinone). Table 323 lists the indications and standard dosages for medications used in the treatment of endometriosis. Figure 2 presents a decision tree for treatment of endometriosis in select patients.

| Medication | Indications | Dosing | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depot MDPA (Depo-Provera) | Pain relief | 150 mg intramuscularly every three months | Common usage in primary care |

| MDPA (Provera) | Pain relief | 30 to 100 mg daily, given orally | Common usage in primary care |

| Combined OCPs | Pain relief | 0.02 to 0.03 mg ethinyl estradiol and 0.15 mg desogestrel daily (cyclically) for six months* | Common usage in primary care |

| Levonorgestrel intrauterine system (Mirena) | Pain relief after surgery | Intrauterine system | Can be placed easily in primary care setting |

| Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (e.g., goserelin [Zoladex], leuprolide [Lupron], triptorelin [Trelstar Depot]) | Pain relief | 3.75 mg of leuprolide injected every four weeks or 3.6 mg of goserelin implanted subcutaneously for six months | Expensive; significant side effects (hypoestrogenic symptoms) |

| Nafarelin (Synarel) | Pain relief | 200 mcg intranasally twice daily for six months | Expensive; significant side effects |

| Danazol (Danocrine) | Pain relief | 200 mg given orally three times daily; 400 mg given orally twice daily for six months | Significant androgenic side effects |

| Gestrinone | Pain relief | 2.5 mg given orally twice weekly for six months | Hot flashes |

Many sources support the empiric use of GnRHas for treatment of the pain associated with endometriosis;27 however, a systematic review found them to be no more effective than OCPs or progestogens24 (Online Table A). Furthermore, GnRHas can have hypoestrogenic side effects.28 These side effects may be alleviated somewhat with add-back therapy (i.e., replacement of hormones blocked by the action of GnRHas) without diminishing the effect of the GnRHa; however, the optimal method of add-back therapy has not been established.27 One small study found the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) to be effective in postoperative treatment for dysmenorrhea.29

| Study | Population/setting | Outcomes | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined OCPs compared with goserelin (Zoladex)A1 | Women of reproductive age, surgically diagnosed/ primary and secondary health care settings | Pain relief, side effects | No significant difference in pain six months posttreatment; significantly more side effects with goserelin |

| Progestogens and anti-progestogensA2,A3 | Premenopausal women, laparoscopically diagnosed/ primary and secondary health care settings | Pain relief, resolution of endometriotic implants, side effects, compliance | Equivalent to other medical therapies for pain (e.g., danazol [Danocrine]), therefore likely effective; scant good data |

| GnRHas compared with placeboA4 | Premenopausal women, laparoscopically diagnosed, between 18 and 50 years of age/gynecologic outpatient clinics | Pain relief and side effects | More effective than placebo; high dropout rates in placebo group |

| GnRHas compared with other medical treatmentsA4,A5 | Premenopausal women, laparoscopically diagnosed, between 18 and 50 years of age/gynecologic outpatient clinics | Pain relief and side effects | Similar effectiveness as other medical treatments (OCPs, gestrinone, danazol); gestrinone possibly more effective; OCPs less effective for dysmenorrhea |

| GnRHas compared with GnRHas plus add-back therapyA4 | Premenopausal women, laparoscopically diagnosed, between 18 and 50 years of age/gynecologic outpatient clinics | Pain relief and side effects | Similar effectiveness; fewer side effects with add-back hormone therapy |

| DanazolA6 | Women of reproductive age, surgically confirmed diagnosis/settings not specified (systematic review) | Subjective symptom relief, objective disease improvement, side effects, compliance, disease recurrence | Significantly more effective than placebo after six months' therapy but with significant side effects (e.g., weight gain, acne) |

| Preoperative hormonal suppression for endometriosis surgery compared with surgery aloneA7 | Various populations/settings not specified (systematic review of11 studies) | Pain relief, disease recurrence, pregnancy rates, adverse effects | Significant reduction in objective disease extent scores, but insufficient evidence to support use; no evidence of decreased disease recurrence or improved pregnancy rates |

| Hormonal suppression after endometriosis surgery compared with surgery aloneA7 | Various populations/settings not specified (systematic review of11 studies) | Pain relief, disease recurrence, pregnancy rates | No benefit; insufficient evidence. No evidence of decreased recurrence or improved pregnancy rates |

| Ovulation suppression for endometriosis-associated subfertility compared with placebo, no treatment, or danazolA8 | Women with visually diagnosed disease who did not conceive after at least 12 months of unprotected intercourse/settings not specified (systematic review) | Pregnancy, adverse outcomes | Not beneficial for improvement of subfertility; multiple side effects |

| Levonorgestrel-releasingintrauterine system (Mirena) for dysmenorrhea after surgeryA9 | Parous women with moderate to severe dysmenorrhea who were undergoing surgery/tertiary care referral center | Pain relief one year after surgery | 10 percent recurrence of moderate to severe dysmenorrhea in treatment group compared with 45 percent in control group |

SURGICAL TREATMENT

No randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have evaluated ablation of endometrial deposits alone. Ablation of endometrial deposits with or without laparoscopic uterine nerve ablation decreases pain (Online Table B).30,31 Presacral neurectomy, a procedure in which the sympathetic nerves from the uterus are divided, may decrease midline abdominal pain.31 Laparoscopic surgery with ablation of endometrial deposits also may increase fertility in women with endometriosis.32 No systematic reviews or meta-analyses have compared laparoscopic drainage and laparoscopic cystectomy for the treatment of ovarian endometriomas. One RCT found cystectomy to be superior to drainage in pain relief at two years.33

| Study | Population | Outcomes | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic review of LUNAB1 | Women with endometriosis and dysmenorrhea | Outcomes Comment Systematic review of LUNAB1 Women with endometriosis and dysmenorrhea Pain relief | LUNA with ablation was not superior to ablation alone. |

| Systematic review that included one study of laparoscopic surgery and LUNA compared with no treatmentB2 | Women with endometriosis and pelvic pain | Increased pain relief at six months | LUNA was used with ablation, so benefit cannot be determined. |

| Systematic review of presacral neurectomy with ablation compared with ablation aloneB1 | Women with endometriosis and dysmenorrhea | No overall difference in pain relief | Women with midline abdominal pain had a significant decrease in pain. |

| Systematic review of two RCTs that evaluated fertility rates after laparoscopic ablation of endometrial depositsB3 | Infertile women 39 years of age with minimal or mild endometriosis | Increase in ongoing pregnancy and live birth rates | Both studies had methodologic flaws. |

Hysterectomy and bilateral salpingooophorectomy are definitive treatments for endometriosis, although there are no RCTs to support this. In a retrospective analysis of women 10 years after hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy, there was a 10 percent incidence of recurrent symptoms; women who had only hysterectomy had a 62 percent incidence of recurrent symptoms.34

CRITERIA FOR APPROPRIATE REFERRAL

Referral is required for definitive diagnosis of endometriosis by laparoscopy or laparotomy and biopsy, or for surgical ablation. Medical treatment with GnRHas or danazol (if the use of OCPs or progestogens proves ineffective) may be expensive with many possible side effects, and these therapies may be outside the range of usual primary care pharmacotherapy. Physicians experienced in the use of GnRHas and danazol may be comfortable prescribing such medications; otherwise, referral is appropriate.

Prognosis

The natural history of endometriosis suggests that the disease may stabilize or resolve on its own. In a small study that randomized patients with endometriosis to progestin or placebo, follow-up laparoscopy after one year showed that regardless of the treatment arm, 47 percent of patients had progression of their endometriosis, 25 percent had disease resolution, and 25 percent were unchanged.35 Endometriosis may recur after surgery whether or not the patients are treated with estrogen replacement. Likewise, postmenopausal women may develop endometriosis if they use hormone therapy.