Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(4):541-543

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

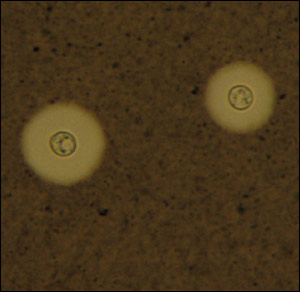

A 48-year-old man with no reported medical history presented to the emergency department with a gradually worsening headache over the past several days. His pain was confined to the occipital area and was accompanied by nausea, vomiting, fever, and chills. Examination revealed neck stiffness, but no other neurologic deficits were identified. Lumbar puncture was performed. Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed a red blood cell count of 20 per μL and a white blood cell count of 922 per μL with 52 percent neutrophils, 32 percent lymphocytes, and 16 percent monocytes. The CSF protein was 119 mg per dL (1.19 g per L; normal range: 15 to 45 mg per dL [0.15 to 0.45 g per L]), and glucose was 28 mg per dL (1.55 mmol per L; normal range: 43 to 70 mg per dL [2.40 to 3.90 mmol per L]). Results of CSF staining are shown in the accompanying figure.

Question

Discussion

The answer is A: C. neoformans meningitis. Cryptococcosis is an invasive fungal infection caused by C. neoformans. Infection through the respiratory tract occurs following inhalation of C. neoformans. The organism disseminates hematogenously and has a propensity to localize to the central nervous system.1 Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis is an important opportunistic infection in immunosuppressed patients, particularly those with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It rarely occurs in patients with CD4 counts greater than 100 per mm3 (0.10 × 109 per L). Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis is the AIDS-defining illness for 60 percent of the patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in whom it is diagnosed.2–4

Examination of the CSF with India ink capsule staining shows the typical encapsulated yeast forms in approximately 75 percent of patients. When results of the India ink examination are negative but a diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis is still suspected, assaying for cryptococcal polysaccharide antigen in the CSF is an option.3,5

Treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in HIV-infected patients involves three phases: induction, consolidation, and maintenance. During induction, patients receive amphotericin B (Fungizone; 0.7 mg per kg per day) and flucytosine (Ancobon; 100 mg per kg per day in four divided doses) for 14 days. In the consolidation phase, patients take fluconazole (Diflucan) in a dosage of 400 to 800 mg daily for eight weeks. During the lifelong maintenance phase, patients take fluconazole in a dosage of 200 mg daily.6,7 Fluconazole maintenance therapy can be stopped in selected patients who are asymptomatic and have a sustained increase in their CD4 counts of greater than 100 cells per mm3 for more than one year.

Treatment of cryptococcal meningitis in patients without HIV infection uses the same induction regimen as in patients with HIV. Consolidation treatment with fluconazole varies from three to six months depending on the clinical presentation and underlying risk factors, and the maintenance phase does not play a significant role because of patients' normal CD4 counts and immunity.

The initial presentation of meningococcal meningitis is the sudden onset of fever, nausea, vomiting, headache, and myalgias and a decreased ability to concentrate in an otherwise healthy patient. A petechial rash often appears as discrete lesions measuring 1 to 2 mm in diameter, most often on the trunk and lower portions of the body. Extreme complications include disseminated intravascular coagulation, shock, myocarditis, and purpura fulminans.8

H. influenzae meningitis used to be a disease occurring mainly in children. However, because childhood vaccination is now routine, H. influenzae meningitis has become relatively more common in adults.8 CSF Gram stain reveals gram-negative bacilli.

L. monocytogenes is an important bacterial pathogen in immunosuppressed patients, neonates, older patients, and pregnant women. The clinical presentation ranges from a mild illness with fever and mental status changes to a fulminant course with coma. Clinical diagnosis can be difficult because of the pleomorphic nature of the bacteria. Thus, CSF Gram stain may be negative or show gram-positive rods and coccobacilli.

S. pneumoniae meningitis is the most common cause of bacterial meningitis. Again, the findings are acute. Neurologic sequelae such as seizures, focal neurologic deficits (including cranial nerve palsies), and papilledema often are associated with pneumococcal meningitis.8 CSF stain findings for selected causes of meningitis are described in the accompanying table.

| Cause of meningitis | CSF stain findings |

|---|---|

| Cryptococcus neoformans | India ink stain shows typical encapsulated yeast forms |

| Haemophilus influenzae | Gram stain reveals gram-negative bacilli |

| Listeria monocytogenes | Difficult to diagnose; Gram stain may show gram-positive rods and/or coccobacilli |

| Neisseria meningitidis | Gram stain reveals gram-negative diplococcus |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | Gram stain reveals gram-positive cocci inpairs |