Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(3):264

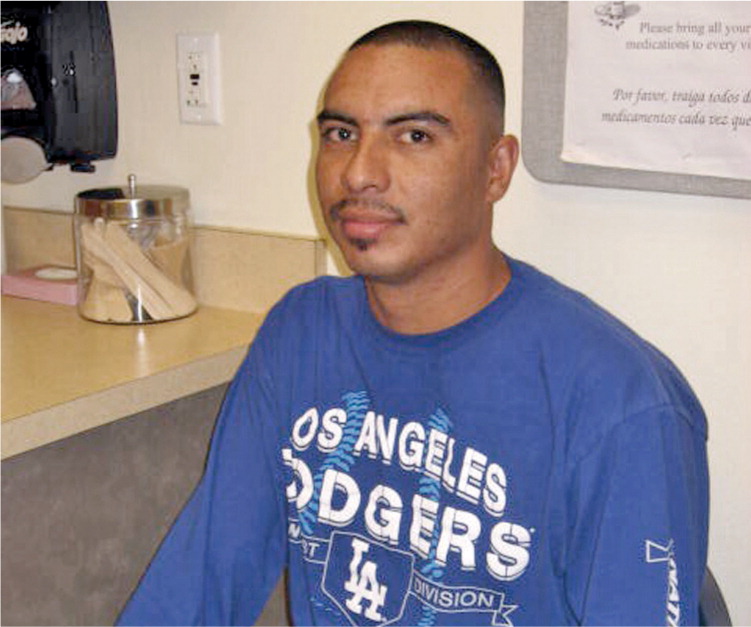

I felt so much anxiety. I couldn't sleep or eat. There was pressure in my chest, and I felt like there were ants crawling all over my body. I was shaking, and I couldn't sit still. I was worried about everything, especially my finances. My car had recently broken down, and I have a wife and three kids to support. When I finally went to see my doctor, I walked away while I was waiting because I was too nervous. I returned the next week, and I'm glad I stayed that time.

My doctor asked me if I was depressed, and I told her I wasn't. She asked if I wanted to sit down, but I told her I couldn't. She asked if I had thoughts of hurting myself or anyone else, and then I started to cry. I cried because I was so scared. I told her that I was afraid of taking a knife to my wife's and kids' throats. I didn't want to hurt them. I love my family. I play soccer with my kids and love spending time with them. My wife is so supportive of me. I don't know why I felt this way.

The doctor asked if I would be willing to get help in the hospital. I was so relieved. I knew I needed help, and I didn't want to feel this way anymore. When the police officer came to get me I was afraid, but he turned out to be a nice guy and made me feel comfortable. I spent the night in the hospital, and felt a little better afterward. They let me go home after 24 hours, and gave me medicine to take every day. It's been several weeks since I left the hospital, and I have been seeing a psychiatrist. I am doing so much better now. Those awful thoughts are gone, and I feel like myself again. Even though I was really scared when my doctor called the police to take me to the hospital, it was the best thing she could have done for me, and I really appreciate it.—m.h.

COMMENTARY

We are all very busy family physicians, with pressure to see as many patients as we can in a day. M.H. came to me during the middle of the busiest morning I had ever experienced as a physician; I was examining 19 patients in only half a day in the public health clinic. My focus was on getting through the day, but something about this patient made me stop and ask about depression. Even when he denied being depressed, I felt the urge to dig a little deeper. If I hadn't taken the extra time to try to make him feel a little more comfortable, he may not have divulged his suicidal and homicidal ideations. Men are often more reluctant to admit they feel depressed, and may present atypically. I often think about what would have happened if this patient had gone home instead of to the hospital. If I hadn't paused, I might never have found out that my patient, too, was in a race against time.