Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(5):341-346

Patient information: A handout on this topic is available at https://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/dysmenorrhea/treatment.html.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Dysmenorrhea is one of the most common causes of pelvic pain. It negatively affects patients' quality of life and sometimes results in activity restriction. A history and physical examination, including a pelvic examination in patients who have had vaginal intercourse, may reveal the cause. Primary dysmenorrhea is menstrual pain in the absence of pelvic pathology. Abnormal uterine bleeding, dyspareunia, noncyclic pain, changes in intensity and duration of pain, and abnormal pelvic examination findings suggest underlying pathology (secondary dysmenorrhea) and require further investigation. Transvaginal ultrasonography should be performed if secondary dysmenorrhea is suspected. Endometriosis is the most common cause of secondary dysmenorrhea. Symptoms and signs of adenomyosis include dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and a uniformly enlarged uterus. Management options for primary dysmenorrhea include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hormonal contraceptives. Hormonal contraceptives are the first-line treatment for dysmenorrhea caused by endometriosis. Topical heat, exercise, and nutritional supplementation may be beneficial in patients who have dysmenorrhea; however, there is not enough evidence to support the use of yoga, acupuncture, or massage.

Dysmenorrhea, defined as painful cramps that occur with menstruation, is the most common gynecologic problem in women of all ages and races,1 and one of the most common causes of pelvic pain.2 Estimates of the prevalence of dysmenorrhea vary widely (16.8% to 81%3), and rates as high as 90% have been recorded.4 Symptoms typically begin in adolescence and may lead to school and work absenteeism, as well as limitations on social, academic, and sports activities.5

Dysmenorrhea is considered primary in the absence of underlying pathology. Onset is typically six to 12 months after menarche, with peak prevalence occurring in the late teens or early twenties. Secondary dysmenorrhea results from specific pelvic pathology. It should be suspected in older women with no history of dysmenorrhea until proven otherwise.6 Symptoms include menorrhagia, intermenstrual bleeding, dyspareunia, postcoital bleeding, and infertility.

Endometriosis is the most common cause of secondary dysmenorrhea.7 The incidence is highest among women 25 to 29 years of age and lowest among women older than 44 years. Black women have a 40% lower incidence of endometriosis compared with white women.8 Table 1 lists risk factors for the development of dysmenorrhea; protective factors include regular exercise, oral contraceptive use, and early childbirth.6

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| A pelvic examination should be performed in all sexually active patients with dysmenorrhea and in those in whom endometriosis is suspected. | C | 11, 20 |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be used as first-line treatment for primary dysmenorrhea. | A | 22 |

| Oral contraceptives may be effective for relieving symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea, but evidence is limited. | B | 27 |

| Combined hormonal contraceptives and intramuscular, intrauterine, and subcutaneous progestin-only contraceptives are effective treatments for dysmenorrhea caused by endometriosis. | B | 11, 25, 28 |

| Risk factor | Odds ratio |

|---|---|

| Heavy menstrual loss | 4.7 |

| Premenstrual symptoms | 2.4 |

| Irregular menstrual cycles | 2.0 |

| Age younger than 30 years | 1.9 |

| Clinically suspected pelvic inflammatory disease | 1.6 |

| Sexual abuse | 1.6 |

| Menarche before 12 years of age | 1.5 |

| Low body mass index | 1.4 |

| Sterilization | 1.4 |

Diagnosis

WHICH SYMPTOMS SUGGEST PRIMARY DYSMENORRHEA?

Characteristic symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea include lower abdominal or pelvic pain with or without radiation to the back or legs, with initial onset six to 12 months after menarche (Table 2).1,9–18 Pain typically lasts eight to 72 hours and usually occurs at the onset of menstrual flow. Other associated symptoms may include low back pain, headache, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, or vomiting.1 A family history may be helpful in differentiating primary from secondary dysmenorrhea; patients with a family history of endometriosis in first-degree relatives are more likely to have secondary dysmenorrhea.1

| Suspected condition | Clinical presentation | Diagnostic evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary dysmenorrhea | Recurrent, crampy, suprapubic pain occurring just before or during menses and lasting two to three days; pain may radiate into the lower back and thighs, and may be associated with nausea, fatigue, bloating, and general malaise; normal pelvic examination findings1 | Diagnosis is clinical; urine tests should be ordered to rule out pregnancy or infection9 |

| Endometriosis | Cyclic (can be noncyclic) pelvic pain with menstruation; may be associated with deep dyspareunia, dysuria, dyschezia, and subfertility; rectovaginal examination findings include fixed or retroverted uterus or reduced uterine mobility, adnexal masses, and uterosacral nodularity10,11 | Transvaginal and pelvic ultrasonography are highly accurate for detecting ovarian and bowel endometriomas; magnetic resonance imaging may be indicated for deeply infiltrating endometriosis11,12; laparoscopy with biopsy and histology is the preferred diagnostic test11,13–16 |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | History of lower abdominal pain in sexually active patients; abnormal pelvic examination findings consisting of cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, and/or adnexal tenderness; other associated clinical features include oral temperature > 101°F (38.3°C) and abnormal cervical or vaginal mucopurulent discharge17 | Saline microscopy of vaginal fluid may show organism; elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level suggests infection; laboratory documentation of cervical infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis is confirmatory; transvaginal ultrasonography is not usually indicated but may show thickened tubes with fluid collection, free pelvic fluid, or tubo-ovarian complex17 |

| Adenomyosis | Usually associated with menorrhagia; may include intermenstrual bleeding; physical examination findings include enlarged, tender, boggy uterus | Transvaginal ultrasonography and, if necessary, magnetic resonance imaging will usually detect endometrial tissue within the myometrium18 |

| Leiomyomata | Cyclic pelvic pain with menorrhagia and occasionally dyspareunia, particularly with anterior and fundal fibroids | Transvaginal ultrasonography can identify fibroids |

| Ectopic pregnancy | History of amenorrhea, abnormal uterine bleeding, severe sharp lower abdominal pain, and/or cramping on the affected side of the pelvis; may present with complications (e.g., hypotension, shock) | Positive urinary human chorionic gonadotropin pregnancy test; pelvic or transvaginal ultrasonography demonstrating extrauterine gestational sac |

| Interstitial cystitis | History of suprapubic pain (usually noncyclic) associated with urinary symptoms (e.g., frequency, nocturia); pain may radiate into the groin and rectum and is usually relieved by voiding; negative pelvic examination findings | Urinalysis; cystoscopy with hydrodistension and biopsy, which may show irritation of the bladder wall mucosa10 |

| Chronic pelvic pain | History of noncyclic pelvic pain for at least six months; pain may radiate anteriorly toward the vagina or posteriorly toward the rectum and is worsened by anxiety; may be associated with dyspareunia and difficulty with defecation; pelvic examination findings may be normal, but burning pain exacerbated by unilateral rectal palpation suggests pudendal nerve entrapment of the affected side10 | Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging along the pudendal nerve to assess the nerve and surrounding structures; if findings on workup are negative, the diagnosis is based on clinical history10 |

About 10% of young adults and adolescents with dysmenorrhea have secondary dysmenorrhea; the most common cause is endometriosis.19 Changes in timing and intensity of the pain or dyspareunia may suggest endometriosis, and menstrual flow abnormalities may be associated with adenomyosis or leiomyomata. A history of sexually transmitted infection or vaginal discharge associated with dyspareunia raises suspicion for pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Asking about a history of sexual trauma is also recommended.10

ARE PELVIC EXAMINATIONS NECESSARY IN ALL WOMEN WITH DYSMENORRHEA?

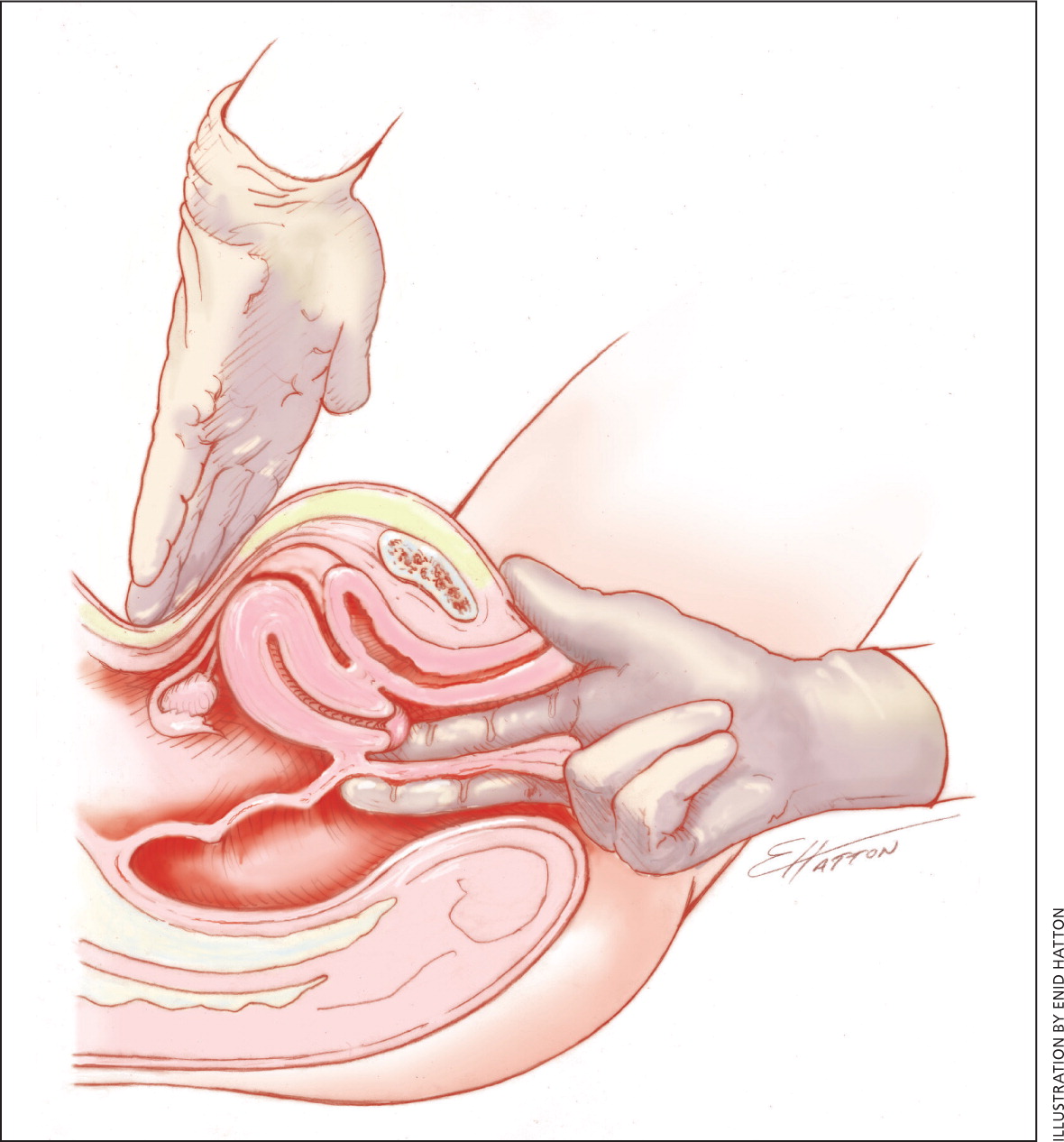

A pelvic examination should be performed in adolescents who have had vaginal intercourse because of the high risk of PID in this population. A pelvic examination is not essential for adolescents with symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea who have never had vaginal intercourse.20 However, if endometriosis is suspected, pelvic and rectovaginal examinations (Figure 1) should be performed.11 Pelvic examination has a 76% sensitivity, 74% specificity, 67% positive predictive value, and 81% negative predictive value for endometriosis.13 Findings are usually normal in patients with primary dysmenorrhea. Findings in those with secondary dysmenorrhea include a fixed uterus or reduced uterine mobility, adnexal masses, and uterosacral nodularity in patients with endometriosis; mucopurulent cervical discharge in those with PID; and uterine enlargement or asymmetry in patients with adenomyosis.10

WHEN SHOULD ADENOMYOSIS BE SUSPECTED?

Adenomyosis is the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the myometrium. Symptoms and signs include dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, and a uniformly enlarged uterus. Diagnosis is usually confirmed through transvaginal ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging.18

WHICH CLINICAL FEATURES DISTINGUISH PID FROM DYSMENORRHEA?

One or more findings of uterine tenderness, adnexal tenderness, or cervical motion tenderness should raise the suspicion for PID.17 Additional criteria include oral temperature greater than 101°F (38.3°C), abnormal cervical or vaginal mucopurulent discharge, abundant white blood cells on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated C-reactive protein level, and laboratory documentation of cervical infection with Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis.

WHICH TESTS ARE INDICATED IN THE EVALUATION OF DYSMENORRHEA?

Transvaginal ultrasonography should be performed if secondary dysmenorrhea is suspected10,15 (Figure 2). It has a 91% sensitivity and 98% specificity, a positive likelihood ratio of 30, and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.09 for detection of bowel endometriosis.16 It also has a high degree of accuracy for detection of ovarian endometriomas.13 Other useful tests include a urinary human chorionic gonadotropin pregnancy test; vaginal and endocervical swabs, a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and urinalysis. Cervical cytology should also be performed to rule out malignancy. Magnetic resonance imaging may be considered as a second-line diagnostic option if adnexal torsion, deep pelvic endometriosis, or adenomyosis is still suspected after inconclusive or negative findings on transvaginal ultrasonography.11,12,18,21

Treatment

WHICH MEDICATIONS ARE FIRST-LINE THERAPY FOR PRIMARY DYSMENORRHEA?

A Cochrane review of 73 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated strong evidence to support nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as the first-line treatment for primary dysmenorrhea22 (Table 323 ). The choice of NSAID should be based on effectiveness and tolerability for the individual patient, because no NSAID has been proven more effective than others. Medications should be taken one to two days before the anticipated onset of menses, and continued on a fixed schedule for two to three days.19,22

| Drug | Dosage | Cost* |

|---|---|---|

| Celecoxib (Celebrex)† | 400 mg initially, then 200 mg every 12 hours | $65 for 10 200-mg capsules |

| Ibuprofen | 200 to 600 mg every six hours | $3 for 24 200-mg tablets |

| Mefenamic acid | 500 mg initially, then 250 mg every six hours | $137 for 12 250-mg capsules |

| Naproxen | 440 to 550 mg initially, then 220 to 275 mg every 12 hours | $4 for 24 220-mg capsules |

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF HORMONAL CONTRACEPTIVES?

Primary Dysmenorrhea. Oral, intravaginal, and intrauterine hormonal contraceptives have been recommended for management of primary dysmenorrhea24–26 (Table 411,24–27 ); however, the evidence supporting their effectiveness is limited. There is a lack of high-quality RCTs demonstrating pain improvement with the use of oral contraceptives27; however, smaller RCTs report response rates as high as 80%.25 Both 28-day and extended-cycle oral contraceptives are reasonable options in women with primary dysmenorrhea who also desire contraception.24,26

| Contraceptive | Cost* |

|---|---|

| Combined oral contraceptives (monophasic or multiphasic) | |

| Norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol 0.25 mg/0.035 mg (Ortho-Cyclen)† | $15 per 28-day pack ($37 brand) |

| Norethindrone/ethinyl estradiol 1 mg/0.035 mg (Ortho-Novum 1/35)† | $17 per 28-day pack ($61 brand) |

| Extended-cycle oral contraceptives | |

| Levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol 0.15 mg/0.03 mg (Seasonique)† | $99 per 91-day pack ($279 brand) |

| Levonorgestrel/ethinyl estradiol 90 mcg/20 mcg (Amethyst)† | $46 per 28-day pack |

| Other hormonal contraceptives | |

| Etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon)† | $791 |

| Etonogestrel/ethinyl estradiol 0.12 mg/0.015 mg vaginal ring (Nuvaring) | $97 per ring |

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena)‡ | $750 plus insertion |

| Medroxyprogesterone 150 mg per mL injection (Depo-Provera)† | $27 per 1-mL syringe ($118 brand) |

Dysmenorrhea Caused by Endometriosis. Combined oral contraceptives are the first-line treatment for dysmenorrhea caused by endometriosis.11,25 A double-blind RCT demonstrated the effectiveness of combined oral estrogen-progestin for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis.28 Several trials have confirmed the effectiveness of oral and depot medroxyprogesterone (Provera), the etonogestrel implant (Nexplanon), and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena).11,25

WHAT IS THE ROLE OF COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES?

There is limited and inconsistent evidence on the effectiveness of nonpharmacologic therapies for primary dysmenorrhea.29 Expert consensus19,24,26 and a small study30 suggest that topical heat may be as effective as NSAIDs, but there is insufficient evidence for acupuncture, yoga, and massage. Exercise22,24,31 and nutritional interventions (supplementation or increased intake of omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin B)19,24,26 may provide some benefit, but the evidence is limited to small RCTs.26

Data Sources: PubMed was searched using the key term dysmenorrhea combined with the terms prevalence, incidence, diagnosis, management, differential diagnosis, pharmacologic therapies, complementary therapies, alternative therapies, nonsteroidal, oral contraceptives, hormonal, exercise, secondary dysmenorrhea, menstrual pain, pelvic pain, endometriosis, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, exercise, behavioral interventions, pelvic ultrasound, laparoscopy, adenomyosis, and sexually transmitted disease. Also searched were the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality clinical guidelines and evidence reports, National Guideline Clearinghouse, Clinical Evidence, Essential Evidence Plus, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Search dates: January and February 2012, and November 2013.