Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(1):22-24

Related editorials: Getting Medicine Right: Overcoming the Problem of Overscreening, Overdiagnosis, and Overtreatment; Improving Quality by Doing Less: Overdiagnosis; and Improving Quality by Doing Less: Overtreatment

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

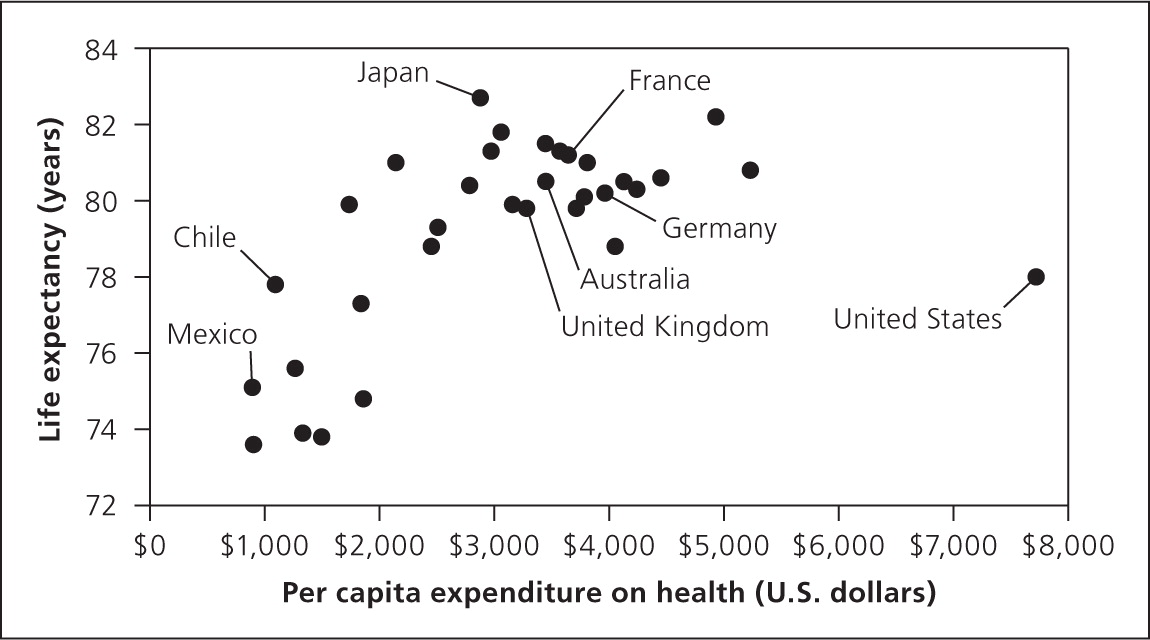

As countries spend more on health care, they usually have some increase in life expectancy. However, as seen in Figure 1, the United States is an outlier.1 The cost for health care per person in the United States is twice that of the typical industrialized country, yet we are not experiencing a commensurate gain in life expectancy. A recent report by the National Research Council documents that the United States ranks at or near the bottom on many indicators of health and life expectancy compared with 17 other high-income countries.2 We are clearly paying for a great deal of health care that is not improving how well or how long we live. This editorial is the first in a series of three that addresses the related issues of over-screening, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment.

The American Academy of Family Physicians and dozens of other medical specialty organizations have been working with the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation as part of the Choosing Wisely campaign (http://www.choosingwisely.org) to address overuse of tests and treatments in medical care. The goal is informed decision making that leads to intelligent and effective patient care choices. Choosing Wisely has released lists of recommendations physicians and patients should question. Examples for family physicians related to screening include Papanicolaou (Pap) smears for women younger than 21 years or without a uterus, screening for osteoporosis in women younger than 65 years who have no risk factors, and early imaging for low back pain in the absence of alarm symptoms. To search Choosing Wisely recommendations relevant to primary care, go to https://www.aafp.org/afp/recommendations/search.htm.

Screening is the attempt to diagnose disease in a preclinical, asymptomatic stage, when treatment may improve patient-oriented outcomes more than it would after the disease causes clinical symptoms. However, not all screening tests are beneficial.3 Overscreening refers to the use of a screening test at ages younger or older than the range recommended by national guidelines, or at a greater frequency (shorter intervals) than recommended. Overscreening also occurs when tests are performed in asymptomatic persons when there is no evidence that the screening will improve patient outcomes. Recent studies have documented extensive over-screening for a number of diseases, including colorectal cancer,4 cervical cancer,5,6 breast cancer,7 and coronary artery disease.8

For example, one study identified more than 24,000 Medicare enrollees who had undergone screening colonoscopy between 2001 and 2003. The study found that approximately one in four underwent a second screening colonoscopy within seven years of their first examination, without any clear indication. This was more likely to happen in patients with more comorbidities (who presumably had more contact with the medical system), those who saw a high-volume colonoscopist, and those who had the procedure in an office setting.4 There was even evidence of overscreening in patients older than 75 years. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening colonoscopy no less than 10 years after normal results on the initial examination; more frequent screening provides little benefit and significantly increases the risk of harm, especially as patients age, leading to a decreased net benefit.9

Guidelines for cervical cancer screening have evolved over the past 20 years, and screening is now recommended every three to five years for average-risk women between 21 and 65 years of age. In 1996, the USPSTF recommended that women who have undergone a hysterectomy for benign disease no longer have a Pap smear.10 However, a study found that 69% of such women had a Pap smear within the previous three years, a percentage that did not change between 1992 and 2002.5 These unnecessary tests lead to at least one intervention in 4% of women during the eight months following the test, including colposcopy and other surgical procedures.6 Over a 30-year period, women of all ages in the United States had four times as many Pap smears as women in the Netherlands, yet there was no difference between the two countries in cervical cancer mortality rates.11

Patients with dementia generally have a shortened life expectancy and are less likely to benefit from mammography. Nevertheless, one study found that 18% of women 70 years and older with severe cognitive impairment had a screening mammography; this was even more common among married, non-Hispanic white women with cognitive impairment and high net worth, one-half of whom underwent screening mammography.7 With a mean life expectancy of just over three years, the test is more likely to increase harms and cause confusion and worry, and is very unlikely to improve outcomes in these vulnerable older persons.

The USPSTF makes a “D” recommendation when a clinical preventive service is not routinely recommended. Table 1 summarizes USPSTF “D” recommendations for screening tests.12 Family physicians should familiarize themselves with this list, understand the rationale for each recommendation,12 and discourage the use of these services among the specified patient groups in their practice. By doing so, physicians can create time and space for discussions about clinical preventive services that are recommended, but often not implemented (such as screening for depression, alcohol misuse, or hepatitis C), while helping patients avoid unnecessary harms and costs. The result will be higher quality, more efficient care, and improved patient outcomes.

| Clinical condition | Population | |

|---|---|---|

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm | Nonsmoking women | |

| Cancer | ||

| Breast (BRCA testing) | Average-risk women | |

| Breast (teaching self-examination of the breast) | All women | |

| Cervical | Women older than 65 years who have had adequate recent screening, and women who have had a hysterectomy for benign disease | |

| Colorectal | Persons older than 85 years, and more often than every 10 years | |

| Ovarian | All women | |

| Prostate | All men | |

| Testicular | All men | |

| Hemochromatosis | All persons | |

| Scoliosis | All children and adolescents | |

editor's note: Dr. Ebell is deputy editor for evidence-based medicine for American Family Physician. Drs. Ebell and Herzstein are members of the USPSTF. This article is their own work and does not necessarily represent the views or policies of the USPSTF.