Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(6):362-370

Related letter: Tips for Facilitating Lifestyle Changes in Low-Income Communities

Patient information: Handouts on this topic are available at https://familydoctor.org/diabetes-and-nutrition/ and https://familydoctor.org/diabetes-and-exercise/.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Healthy eating and increased physical activity can prevent or delay the onset of diabetes mellitus and facilitate diabetes management. Current guidelines recommend long-term weight loss of 5% to 7% of body weight and 150 minutes of at least moderate-intensity physical activity per week for most patients with prediabetes and diabetes. Techniques to assess and facilitate adherence to these lifestyle changes can be practical in primary care. During office visits, physicians should assess and gradually encourage patients' readiness to work toward change. Addressing patients' conviction and confidence can be effective in moving them toward action. Long-term goals are best separated into highly specific short-term outcome goals and achievable behavior targets. Lifestyle goals and targets should be tailored to patients' preferences and progress while building confidence in small steps. Screening for diabetes-related attitudes, expectations, and quality of life, and addressing psychosocial factors, both favorable and unfavorable, can facilitate the likelihood of success. Follow-up contact with patients helps maintain and expand progress by reviewing self-monitored goals, targets, and achievements; finding opportunities to encourage and empower; reviewing slips, triggers, and obstacles; and negotiating further customization of the plan.

Approximately 9% to 10% of the U.S. population has type 2 diabetes mellitus, including estimated undiagnosed cases.1 From 1980 to 2014, the prevalence of diagnosed type 2 diabetes in the United States quadrupled. However, the incidence of new cases of diagnosed diabetes peaked in 2008 and has since declined, suggesting that the overall prevalence may gradually level off.2 Older age, obesity, and physical inactivity are risk factors directly related to the development of diabetes.3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with prediabetes should be referred to a structured intensive lifestyle intervention program (e.g., the National Diabetes Prevention Program). | A | 3, 8–10 |

| Patients with prediabetes who are overweight or obese should be encouraged to lose at least 7% of body weight as a long-term goal. | A | 3, 8–10 |

| Patients with prediabetes should be encouraged to engage in 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity (e.g., brisk walking). | A | 3, 8–10 |

| Receptive patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus should be provided a structured intensive lifestyle intervention program (e.g., using the Look AHEAD [Action for Health in Diabetes] intervention materials). | B | 3, 11, 12 |

| Patients with type 2 diabetes who are overweight or obese should be encouraged to lose at least 5% of their body weight as a long-term goal. | C | 3, 11, 12 |

| Patients with type 2 diabetes should be encouraged to engage in 150 minutes per week of moderate-to vigorous-intensity aerobic exercise over three or more days, with no more than two days between exercise bouts, as well as moderate to vigorous resistance training two or three days per week. | C | 3 |

Prediabetes, a state of increased risk of developing diabetes, affects an estimated one in three U.S. adults, which equates to 86 million persons. Nine out of 10 of these persons do not know they have it.4 Prediabetes is diagnosed with one of the following criteria: a fasting plasma glucose level of 100 to 125 mg per dL (5.6 to 6.9 mmol per L), a two-hour plasma glucose level of 140 to 199 mg per dL (7.8 to 11.0 mmol per L) during a 75-g glucose tolerance test, or an A1C level of 5.7% to 6.4%.5 Without intervention, 15% to 30% of those with prediabetes develop diabetes within five years. Once these patients are identified, lifestyle change that focuses on weight loss, increased physical activity, and behavior skill development can be encouraged.2,4,6

Patients with prediabetes should be referred to a structured intensive lifestyle intervention program (e.g., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Diabetes Prevention Program).3,7 Weight loss of 7% of body weight and a long-term goal of 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity physical activity are recommended for patients with prediabetes. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)—a large, multicenter, randomized clinical trial on the effect of weight loss through lifestyle changes on the development of diabetes—demonstrated that intensive lifestyle intervention can delay the onset of type 2 diabetes by about four years and reduce overall diabetes incidence by 34% over 10 years.8 Diabetes prevention studies in China and Finland found similar results.9,10

For patients with type 2 diabetes who are overweight or obese, the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study, a multicenter, randomized controlled trial, found that intensive lifestyle intervention could yield weight loss of at least 5% of initial body weight, with improved glycemic control and reduced need for glucose-lowering medications.3,11,12 Aerobic exercise and resistance training also improve blood glucose control.13

In the DPP and Look AHEAD studies, the interventions provided intensive coaching on healthier eating, increased physical activity, and behavior techniques. The Look AHEAD study updated the DPP curriculum, adapting it for diabetes (rather than prediabetes) and greater use of group interventions. The program curricula are summarized in Table 1.14,15 Resources for program details are listed in eTable A and include Prevent T2, which is a community-based program available to patients in some locations nationwide.

| Curriculum component | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Model | Personalized coaching to tailor motivational enhancement and skill development to suit the participant, using a mix of group and individual sessions | |

| Goal setting | Long-term goals broken into small daily and weekly behavior goals with planned implementation tracking, and homework | |

| Diabetes Prevention Program goal: 7% weight loss and 150 minutes of weekly physical activity | ||

| Look AHEAD goal: 10% weight loss and 175 minutes of weekly physical activity | ||

| Knowledge | USDA food pyramid (note that USDA updated its consumer guidance to MyPlate in 2011), reading food labels, principles of aerobic fitness (frequency, intensity, time, type), and exercise safety | |

| Skill development | ||

| Self-monitor | Weigh/measure/estimate food quantity; track carefully | |

| Measure heart rate and perceived level of exertion; track carefully | ||

| Decrease favorite unhealthy foods | Eat less often, in smaller portions, and/or substitute healthier foods and cooking methods | |

| Look AHEAD additionally encouraged the use of commercial replacement meals for breakfast and lunch during the first six months | ||

| Manage eating out | Plan ahead, be assertive, develop stimulus control, and make healthy food choices | |

| Prioritize/schedule physical activity | Engage in bouts of exercise, such as brisk walking | |

| Incorporate lifestyle activities, such as taking stairs instead of elevators | ||

| Develop stimulus control | Change environment to minimize triggers for unhealthy behavior and maximize triggers for healthy behavior | |

| Limit times and places of eating | ||

| Manage social cues | Confront social pressure to overeat | |

| Develop social cues/relationships that promote healthy behaviors | ||

| Develop specific strategies for coping with parties, vacations, and holidays | ||

| Develop problem-solving techniques | Check for cues (e.g., surroundings, social situations, thoughts, feelings) | |

| Follow steps: describe the problem-related chain of events, brainstorm options for resolving the problem, pick one, make a plan, try it | ||

| Manage negative thoughts | Identify common patterns of self-defeating thoughts and counter with positive statements | |

| Manage slips | Track triggers and reactions; plan for them | |

| Manage stress | Identify stress early and practice breathing or self-soothing techniques; exercise | |

| Keep motivated | Add variety, set new goals, join in friendly competition, seek social support, review/share person; reasons for participating, track personal successes to date | |

| Condition | Resource | Description and website |

|---|---|---|

| Prediabetes | Prevent T2 | Detailed teaching materials for a one-year program; updated from the original Diabetes Prevention Program intensive lifestyle intervention |

| The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognizes such programs, and to date, this program is offered by 1,118 community agencies across the United States | ||

| http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/prevention/index.html | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Look AHEAD | An outline of the treatment sessions in the Look AHEAD study |

| https://www.lookaheadtrial.org/publicresources/interventionmaterial.cfm |

Impact of Timing

The American Diabetes Association recommends intensive lifestyle intervention for patients with type 2 diabetes who are overweight or obese and who are ready to achieve weight loss.3 The American Academy of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends structured counseling and meal replacement for patients with an increasing burden of obesity or related comorbidities.16 In patients who are overweight or obese with at least one additional risk for cardiovascular disease, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends offering or referring for intensive behavior counseling interventions to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for the prevention of cardiovascular disease.17

According to the Look AHEAD study, the highest probabilities of one-year diabetes remission occurred among participants in the intervention group who had less than a two-year history of diabetes (21.2% remitted), had low initial A1C values (17.1% remitted), and were not receiving antihypertensive medications (15.2% remitted).12 Regardless of whether lowered blood glucose and A1C levels represent true remission, this suggests that patients early in the course of diabetes may experience the most benefit from intensive lifestyle interventions.

Adapting these approaches to office practice poses a challenge not necessarily addressed in research trials, which carefully select their study populations and have access to resources that are not readily available in the office and community. The following sections offer a practical approach for working with patients who have diabetes to assess their readiness for lifestyle change, build confidence, develop individualized plans with clear goals, address obstacles, and help maintain goals.

Assessing Patients' Readiness for Change

Patients vary in their adherence to different self-management tasks. A patient may be diligent about blood glucose monitoring but nonadherent to healthier eating plans. When working on behavior change, it is best to carefully assess each behavior separately and work on only one or two major behaviors per visit.

| Stage | Behavior | Physician's goal for visit to move patient forward | Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precontemplation | Not considering change | Move toward thinking about change | Encourage patients to talk:

|

Emphasize patients' autonomy:

| |||

| Assess conviction and confidence | |||

| Contemplation | Considering change | Move toward preparing for change | Continue the conversation:

|

| Assess conviction and confidence | |||

| Preparation | Preparing for change (e.g., reading about diets, asking a friend about a gym) | Move toward taking action | Praise preparation; discuss options; assist in setting initial goals and behavior targets; set a start date |

| Action | Establishing the change | Maintain change | Praise all efforts; encourage one or two small, realistic steps; begin to anticipate obstacles |

| Maintenance | Struggling to maintain the gains | Maintain change | Praise all efforts; encourage one or two small, realistic steps; help patient manage obstacles and slips |

| Ask about benefits noticed (e.g., clothes looser, chores easier, better endurance) | |||

| Identification | Incorporating the change into routine and view of self (e.g., pattern is now automatic; there is little temptation to relapse) | Maintain change | Praise all efforts |

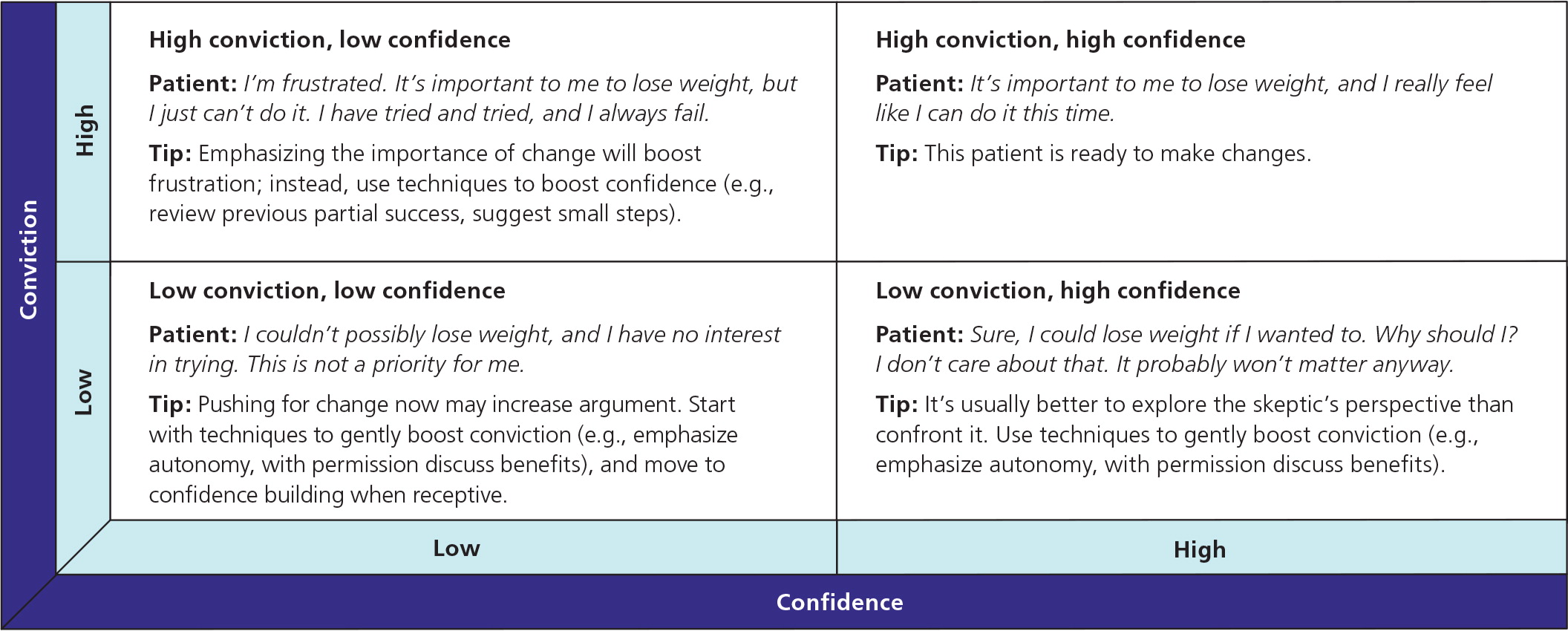

If patients do not seem ready to change (see the pre-contemplation or contemplation stages in Table 218,19), the physician should assess their conviction (i.e., how important it is for them to change) and confidence (i.e., how certain they are that they can change).20 Patients present differently when they have low confidence, low conviction, or both (Figure 1).20 Identifying the pattern helps determine the most likely techniques to move them to readiness (Table 318,20 ). For any given office visit, the physician should pick one or two techniques for enhancing conviction or confidence.18,20

| Sample situation | Suggested conversation starters |

|---|---|

| Enhancing conviction | |

| If conviction is very low, emphasize patient autonomy | “Of course, this decision is clearly up to you, as it should be. My job is not to talk you into something, but it is my job to make sure you understand the implications to your health. Can we talk about some of these implications?” |

| If conviction is very low, ask permission to provide new information; vary the message each visit | “I'd like to talk to you about some new information on the benefits of modest increases in exercise. Are you interested?” |

| Identify ambivalence to better understand the patient's perspective; avoid hard confrontation, which may make the patient defensive | “So, you have considered working on this before, but you do not like people telling you what to do.” |

| Identify barriers to change | “What are some challenges to increasing your activity level?” |

| Brainstorm solutions to barriers | “In the past, you have stopped exercising after a few weeks because of time conflicts. Could you make this a part of your weekly routine if you start with briefer workouts just twice a week? How would that work?” |

| Address stated worries directly | “Because you are uncomfortable exercising in public, let's think of some other ways to increase your physical activity.” |

| Discuss pros and cons; have the patient list the benefits and costs of no change vs. change; to engage the patient, begin with benefits of no change; summarize and let the patient draw conclusions | “We have talked several times about making some changes to your eating patterns. Clearly there are things you like about your current diet that make it hard to change. Tell me about that.” |

| Take a hypothetical look into the future | “So you're not too sure about changing your diet. Let's imagine for a moment that you did make this change. How do you think you would feel a year from now?” |

| Enhancing confidence | |

| Facilitate the shift from viewing previous attempts as failures to partial successes from which the patient can learn | “Most people attempt to lose weight several times with partial success before they succeed for good. Succeeding for good means learning from previous attempts what works and what does not work for you. Let's discuss what you have learned about what works and does not work for you.” |

| Review previous change attempts and praise positive steps | “Have you tried this before? How long did you continue that effort? What helped you succeed for that long? What benefits did you notice? What do you think will work for you now? Tell me about some of the other things you have successfully changed in the past.” |

| Anticipate difficulties; ask about what triggered previous slips and relapses, and what might make it difficult now; brainstorm ways to break a pattern of slips by anticipating triggers and planning solutions | “What made you stop previous efforts? What might help with those obstacles now?” |

| Coach the patient to select small, easy steps based on previous experiences and preferences; if the patient sets a challenging initial goal that seems unrealistic, do not criticize it, but check confidence | “How confident are you that you could get up every day this week at 5:00 a.m. to exercise for 90 minutes?” |

| If confidence is weak: “How might you adjust that goal so you are highly confident you can do it this week?” | |

For patients who are ready to change, the following approach is recommended.

SET CLEAR OUTCOME GOALS AND BEHAVIOR TARGETS

For patients with type 2 diabetes who are overweight or obese, a long-term weight loss goal of 5% percent of body weight is recommended.3,11,12 For all patients with type 2 diabetes, moderate to vigorous aerobic exercise for least 150 minutes per week (spread over three days or more with no more than two consecutive days between bouts), moderate to vigorous resistance training at least two or three days per week, and reduction of sedentary time are recommended.3,13

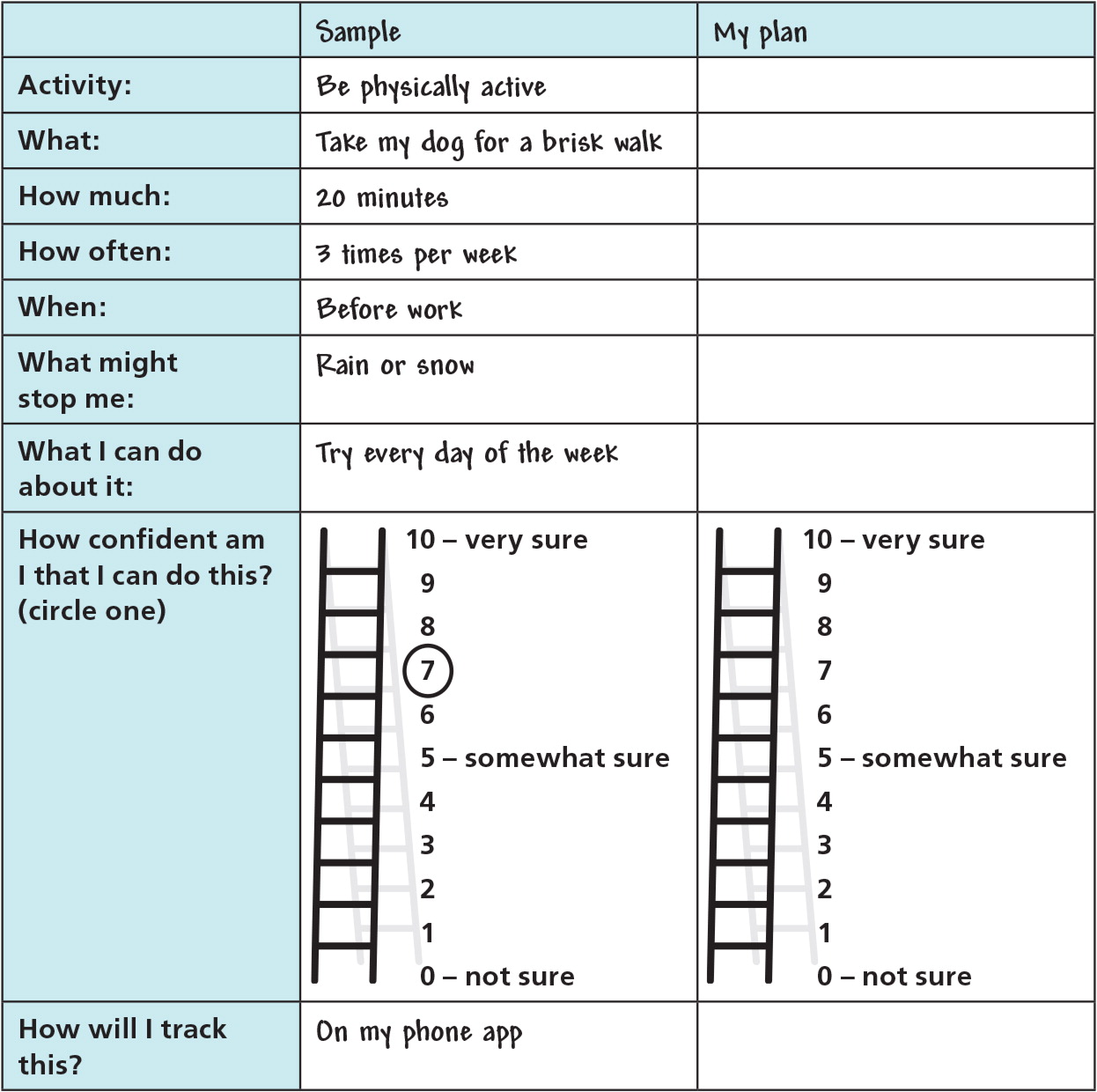

Behavior change is maximized by focusing on small steps in the short term.15,21 It is best to separate outcome goals (e.g., decreasing A1C level, 5% weight loss) into specific behavior targets the patient can accomplish (e.g., control food portions, walk regularly, track changes, attend a class, be assertive with persons who undermine change). The SMART approach to goal setting includes developing specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound behavior targets.22 A lifestyle action plan is used to develop such behavior targets with patients (Figure 2).

Patients should start small and gradually increase daily or weekly behavior targets regarding healthier eating, increased physical activity, and development of related behavior skills. For example, the physical activity target can be increased gradually from 10-minute periods of any enjoyable, moderate physical activity to more intense activity for longer periods. The patient can build confidence in small steps, with each step having a higher likelihood of lasting success. Small steps also yield many opportunities for praise.

INDIVIDUALIZE THE PLAN

Weight Loss

Lifestyle programs of healthier eating, increased physical activity, or both can create an energy deficit of 500 to 750 kcal per day, which may result in weight loss. Because different diets with similar caloric restriction provide similar weight loss, the choice of diet should be based on patient preferences, risks, and comorbidities.3,23 Physicians should work with patients to select a plan they can adhere to for the long term. The DPP and Look AHEAD studies began with each participant's usual diet and then taught skills to modify the diet toward healthier options and portions. The Look AHEAD study also offered several commercially available packaged replacement meals for breakfast and lunch to initially facilitate portion control. There is support for both approaches11: (1) start with the patient's existing diet and coach to gradually modify it, or (2) educate the patient about options for structured diets or meal replacement, and have the individual choose the one he or she is most likely to follow over time.

Physical Activity

Although the recommended exercise goals may seem ambitious for many persons with diabetes, lifestyle programs in the DPP and Look AHEAD studies increased participant activity by implementing small steps gradually. Begin with brief bouts of moderate physical activity selected with the patient (e.g., brisk walking or similar physical effort at bicycling, dancing, yard work, or other activity of interest).14,15,21

ADDRESS PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS

Physicians should ask patients about friends and family who are supportive or have similar goals, and recommend that patients nurture relationships with those who promote healthy behaviors. Asking about persons who undermine progress or confidence (e.g., a family member who pressures them to eat or mocks their efforts) is also important. The DPP program included training in assertiveness and problem-solving skills to address such challenges. The American Diabetes Association recommends periodic screening for diabetes-related attitudes, expectations, and quality of life; availability of practical resources (e.g., financial, social, emotional); and psychiatric symptoms and history.3 Patients who are having difficulties with basic needs (e.g., housing, finances, job, safe environment) have little motivation to address complex long-term lifestyle issues. These patients are better served through case management, which addresses immediate needs and ultimately improves the likelihood of treatment adherence.

Maintaining Lifestyle Changes

Achieving permanent changes in diet and physical activity patterns is a multiyear project. The longer the period of intervention, the more likely that improvements in weight loss and physical activity will be maintained.3,11,24 Lifestyle interventions should begin with frequent contacts and then a slow taper. Because nonphysician members of the health care team are increasingly involved with between-visit contacts, a portion of these contacts may be done by telephone or secure messaging,25,26 although there is currently little evidence to direct the best practice approach.

REVISE THE ACTION PLAN

Physicians should review the lifestyle action plan with patients at each visit (Figure 2). Short-term targets should be adjusted based on patient progress. It is best to develop only one to two additional behavior tasks per visit, starting with the simplest step that is most likely to result in change.15

ENCOURAGE AND EMPOWER

Whether the physician is leading the change effort or is part of a team approach, taking the time to ask about any behavior accomplishments and offering praise can be powerful motivators to continue the effort. Encouragement should be offered at each visit. Physicians should ask patients about behavior targets previously discussed, confirm how the targets are tracked, and review basic information about diabetes. Asking about benefits noticed (e.g., looser-fitting clothes, better endurance, less sweating) is also important. For patients quick to see failure, the focus should be on partial successes compared with their previous level.

PLAN SELF-MONITORING

Because long-term change is more likely when patients systematically track their own behavior, physicians should provide or recommend a simple tracking system, strongly encourage its use, and follow up during office visits. In the DPP and Look AHEAD studies, patients were taught to track all food consumption and physical activity, and were gradually coached to learn what works for them.15,21

Popular consumer fitness trackers and phone apps are sufficiently reliable to track physical activity, such as walking and running, for the purposes of motivating behavior change.27–29 Similarly, dietary tracking through phone apps has improved significantly. A variety of applications offer extensive lists of foods found in grocery stores and restaurants, track daily nutrition totals (e.g., calories and carbohydrates), and automatically generate favorites to facilitate data entry. Such tracking software may additionally include goal setting, support through social networking, reminders, reinforcement for achieving goals, and the ability to review achievements over time.30

Although there is little evidence clarifying the optimal features for this emerging lifestyle technology, it seems clear that the best tracking system for patients is the one they are likely to use regularly.

HELP WITH THE STRUGGLE

The maintenance phase is often a period of struggle (Table 2).18,19 It is common for circumstances to trigger occasional slips. Slips and relapses both begin with a mistake. If the patient quickly returns to the change effort, the mistake is considered a slip; however, if the patient reverts to a previous stage, it is considered the beginning of a relapse. Persons who view a slip primarily as their personal failure tend to feel guilt and shame, and have increased risk of relapse. Persons who view a slip as the result of difficulty coping effectively with a specific high-risk situation are more likely to want to learn from the mistakes and develop effective ways to handle similar situations in the future.31 Patients develop the latter perspective when the physician empathically recognizes the struggle and asks about slips and obstacles. A helpful approach involves focusing on specific examples and prompting the patient to brainstorm about possible triggers and how to overcome them next time. Commonly cited precipitants include negative emotions, interpersonal conflicts, social pressure, time pressure, and celebrations. A person who can execute effective coping skills is less likely to relapse (Table 4).7,15,21 A trial-and-error approach should be in the forefront—a slip is not considered a failure but rather an opportunity to learn what works and what does not work in overcoming a particular obstacle.

| Skill | Behavior target | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Controlling cues | Learn to recognize and change environmental and social cues for eating and physical activity | Shop from a list; eat in one place in the house; add exercise cues to rooms in the house; add physical activity to social life |

| For example, scan the house and replace visible high-calorie snacks with bowls of fruit; eliminate piles of clutter at the bottom of the stairs by walking up each time you have something to bring up; put exercise equipment (e.g., sneakers, mats, bikes, tracking sheets) in busy areas; schedule physical activity reminders in your calendar | ||

| Problem solving | Use a problem-solving approach to overcoming obstacles | Describe, brainstorm, choose, plan, try and see For example:

|

Choose an option.

| ||

| Cognitive change | Respond to common negative thoughts | Recognize “all or nothing” thinking, excuses, competition with others, and self-defeating thoughts; use thought stopping and reality testing to break patterns For example, when thinking “I just blew my diet. I knew I couldn't do this. I give up.” Catch the negative thoughts, mentally think “Stop!” and evaluate realistically: “I am doing much better overall this week than a month ago. What triggered this slip? What can I learn from that?” |

| Relapse prevention | Anticipate slips and get back on track | Identify previous triggers of slips; plan ahead for likely triggers; challenge the idea that a slip means failure; problem solve about how to deal with triggers |

| Avoiding boredom | Vary physical activity to keep motivated | Change some aspect of physical workout each month; take cooking classes |

| Coping | Learn stress management techniques | Prevent stress by saying no, asking for help, setting realistic goals, problem solving, organizing, planning, and prioritizing |

| Cope with unavoidable stress by identifying the source, taking breaks, practicing self-soothing strategies, relaxing, meditating, practicing mindfulness, engaging in physical activity, and using social support | ||

| Social support | Enhance support for lifestyle change | Involve significant others in new activities; develop new social supports compatible with lifestyle changes; address family or friends who undermine confidence and progress |

| Urge response | Recognize escalating urge and take action | Leave a challenging situation; avoid situations that limit the ability to leave or be assertive; urge response is important early in maintenance as skills and confidence are developing |

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Koenigsberg, et al.32

Data Sources: Literature searches were performed using the OVID Med-line Database with key terms prediabetes, prediabetic state, and diabetes mellitus, crossed with lifestyle, diet, exercise, physical activity, weight reduction programs, patient compliance, and adherence. The search was limited to randomized controlled trials, review articles, or meta-analyses, with studies limited to those in English with human participants. Later searches were done for specific areas such as follow-up publications on major studies (Diabetes Prevention Program, Look AHEAD, Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study, Malmo Study, Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study) or meta-analyses for relevant areas (e.g., diet, exercise). Also searched were AFP archives, Guideline.gov, Cochrane database, AHRQ.gov, CDC.gov, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: November 2015, January to March 2016, October to December 2016, and April 2017.