Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(2):97-106

Related letter: Strangulation as a Cause of Dysphagia

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Dysphagia is common but may be underreported. Specific symptoms, rather than their perceived location, should guide the initial evaluation and imaging. Obstructive symptoms that seem to originate in the throat or neck may actually be caused by distal esophageal lesions. Oropharyngeal dysphagia manifests as difficulty initiating swallowing, coughing, choking, or aspiration, and it is most commonly caused by chronic neurologic conditions such as stroke, Parkinson disease, or dementia. Symptoms should be thoroughly evaluated because of the risk of aspiration. Patients with esophageal dysphagia may report a sensation of food getting stuck after swallowing. This condition is most commonly caused by gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional esophageal disorders. Eosinophilic esophagitis is triggered by food allergens and is increasingly prevalent; esophageal biopsies should be performed to make the diagnosis. Esophageal motility disorders such as achalasia are relatively rare and may be overdiagnosed. Opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction is becoming more common. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy is recommended for the initial evaluation of esophageal dysphagia, with barium esophagography as an adjunct. Esophageal cancer and other serious conditions have a low prevalence, and testing in low-risk patients may be deferred while a four-week trial of acid-suppressing therapy is undertaken. Many frail older adults with progressive neurologic disease have significant but unrecognized dysphagia, which significantly increases their risk of aspiration pneumonia and malnourishment. In these patients, the diagnosis of dysphagia should prompt a discussion about goals of care before potentially harmful interventions are considered. Speech-language pathologists and other specialists, in collaboration with family physicians, can provide structured assessments and make appropriate recommendations for safe swallowing, palliative care, or rehabilitation.

Many people occasionally experience difficult or impaired swallowing, but they often adapt their eating patterns to their symptoms and do not seek medical attention.1 Among those who do seek care, the most common causes are generally benign and self-limited, and serious or life-threatening conditions are rare. However, many older adults with progressive neurologic disease have significant but unrecognized dysphagia, which increases their risk of aspiration pneumonia and malnourishment. In these patients, the diagnosis of dysphagia should prompt a discussion about goals of care. Understanding the basic pathophysiology of swallowing and the etiologies and clinical presentations of dysphagia allows family physicians to distinguish between oropharyngeal and esophageal pathology, make informed management decisions, and collaborate appropriately with specialists.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not order “formal” swallow evaluation in stroke patients unless they fail their initial swallow screen. | American Academy of Nursing |

| Do not recommend percutaneous feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia; instead, offer careful hand feeding. | American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine |

| American Geriatrics Society | |

| AMDA – The Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine |

Pathophysiology

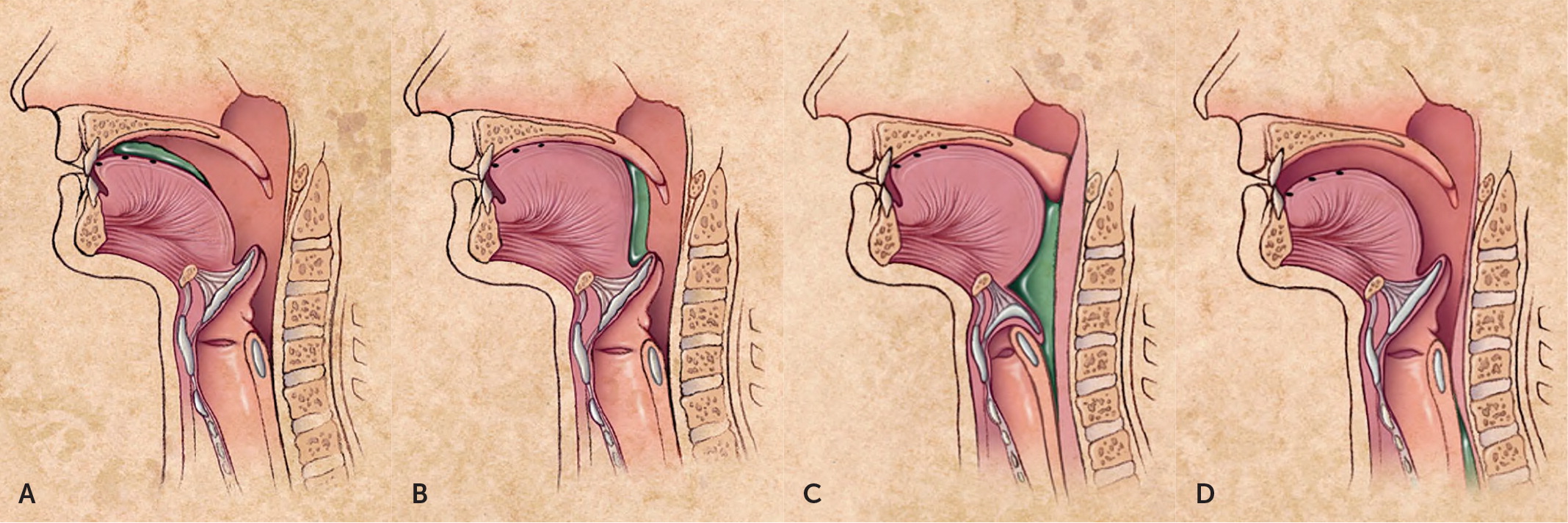

Swallowing (deglutition) is a complex process involving voluntary and involuntary neuromuscular contractions coordinated to permit breathing and swallowing through the same anatomic pathway (Figure 1).2 Deglutition is commonly divided into oropharyngeal and esophageal stages. In the oropharyngeal stage, food is chewed and mixed with saliva to form a bolus of appropriate consistency in the mouth. With the initiation of the swallow, the bolus is propelled into the oropharynx by the tongue. Other structures simultaneously seal the nasopharynx and larynx to prevent regurgitation or aspiration, and the lower esophageal sphincter begins to relax. In the esophageal stage, the food bolus passes the upper esophageal sphincter and enters the esophageal body, where it is propelled by peristalsis through the midthoracic and distal esophagus and into the stomach through the now fully relaxed lower esophageal sphincter.3,4

Oropharyngeal Pathology

Some chronic conditions, such as poor dentition, dentures, dry mouth (xerostomia), or medication adverse effects, may be poorly tolerated in patients who also have progressive oropharyngeal dysfunction. Tardive dyskinesia with choreiform tongue movements related to long-term antipsychotic use may cause decompensation in older adults; it also may cause dysphagia in younger patients.8 Chronic cough related to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor use may interfere with swallowing or be mistaken for aspiration.

| Progressive chronic disease (geriatric syndrome) Stroke Parkinson disease Alzheimer and other dementias Sarcopenia Neuromuscular disease Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis Myasthenia gravis Multiple sclerosis Dermatomyositis/polymyositis (myopathies) Antipsychotic medications* | Structural causes Head and neck cancers Recent surgery or radiation for head and neck cancers (altered anatomy) Chemoradiation-induced mucositis and edema (short term) Zenker diverticulum Cervical osteophytes Lymphadenopathy Goiter Cricopharyngeal bar | Oral causes Poor dentition or dentures Dry mouth (i.e., xerostomia) Medications causing dry mouth (e.g., alpha and beta blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, anticholinergics, anti-histamines, anxiolytics, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, muscle relaxants, tricyclic antidepressants) Antipsychotic medications* |

Esophageal Pathology

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease and esophagitis (30% to 40%) |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis* |

| Functional dysphagia |

| Functional esophageal disorders (20% to 30%)† |

| Functional heartburn |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (nonerosive) |

| Globus pharyngeus‡ |

| Reflux hypersensitivity |

| Medications (5%) |

| Pill esophagitis (direct irritation associated with ascorbic acid, bisphosphonates, ferrous sulfate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, potassium chloride, quinidine, and tetracyclines) |

| Reflux caused by decreased tone of lower esophageal sphincter (associated with alcohol, anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, caffeine, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, and tricyclic antidepressants) |

| Structural or mechanical conditions (5%) |

| Esophageal or peptic stricture (caused by erosive esophagitis) |

| Foreign body or food impaction (acute-onset dysphagia) |

| Malignancy (esophageal or gastric cancer, mediastinal mass with extrinsic compression) |

| Schatzki ring |

| Esophageal motility disorders (< 5%)§ |

| Absent contractility |

| Achalasia |

| Distal esophageal spasm |

| Esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction |

| Hypercontractile (jackhammer) esophagus |

| Hypercontractile motility disorders |

| Opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction¶ |

| Infections (< 5%) |

| Candida esophagitis |

| Cytomegalovirus esophagitis |

| Herpes simplex virus esophagitis |

| Rheumatologic conditions (< 5%) |

| Systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) |

GASTROESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

GERD and recurrent acid exposure result in changes ranging from submucosal inflammation and dysmotility to erosive esophagitis and stricture. Patients with GERD may experience dysphagia even in the absence of apparent mucosal damage.16

EOSINOPHILIC ESOPHAGITIS

FUNCTIONAL ESOPHAGEAL DISORDERS

Like irritable bowel syndrome or functional dyspepsia, functional esophageal disorders are thought to be caused by abnormalities of gut–brain interaction and central nervous system processing. People with these conditions may be hypervigilant about minor symptoms or hypersensitive to even physiologic amounts of acid.18 Patients may report dysphagia, although chest pain and heartburn are more common.19 These disorders may account for many patients who report intermittent difficulties with swallowing but never seek care,1 as well as those in whom no explanation is found even after extensive investigations.15

MEDICATIONS

Medications may cause dysphagia as a result of direct mucosal injury (pill esophagitis), impaired esophageal motility, or lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and reflux.

OBSTRUCTIVE LESIONS

ESOPHAGEAL MOTILITY DISORDERS

Esophageal motility disorders such as achalasia, distal esophageal spasm, and systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) are rare. Similar to opioid-induced bowel dysfunction and constipation, opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction, although not as common, is being increasingly recognized.20 Because this condition is often indistinguishable from other esophageal motility disorders, its prevalence is unclear.21

Initial Evaluation

The first step in the evaluation of a patient with dysphagia is to distinguish between oropharyngeal and esophageal pathology, based on characteristic symptoms. Clinical features and their temporal profile (Table 313,14,22), in addition to physical examination findings (Table 413,14), may suggest specific diagnoses and guide further testing and management.

| “What about swallowing?” Effective initial question for screening; as effective as longer screening instruments for prompting further questioning.22 “What happens when you swallow? Does swallowing make you cough?” Feeling that food is stuck suggests esophageal origin, regardless of the perceived location. Trouble initiating a swallow, choking, coughing, or nasopharyngeal regurgitation suggests oropharyngeal dysphagia. “How long has this been occurring? Is it getting worse? Do you hesitate to go out to eat because of it?” Acute symptoms may be caused by pill esophagitis, infection, or foreign body impaction. Intermittent symptoms suggest intermittent use of medications or opioids, esophageal motility disorders, or inconsistent denture use. Progressive or worsening symptoms suggest malignancy. Dysphagia may lead to social isolation. “Do you have trouble chewing your food?” Bruxism and jaw pain suggest temporomandibular joint arthritis or pain disorders. Trouble chewing food suggests poorly fitting dentures, dental disease, or xerostomia. Weakness with chewing suggests myasthenia gravis, giant cell arteritis, or myopathy (dermatomyositis). “What gets stuck? Solids only? Solids and liquids?” Trouble with liquids and solids suggests an esophageal motility disorder (e.g., achalasia). Trouble with liquids only suggests oropharyngeal pathology. Trouble with solids only suggests a mechanical obstruction of the esophagus, either intrinsic (stricture, web, or tumor) or extrinsic (mediastinal mass or thyromegaly). “Do you have any other symptoms?” Dyspepsia suggests a complication of reflux (e.g., stricture). Halitosis with regurgitation may be due to an esophageal diverticulum or achalasia. Weight loss from dysphagia suggests neoplasia or advanced disease. “What medications do you take, including over-the-counter medications? Do you smoke? How much alcohol do you drink? Do you use opioids?” Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, potassium chloride, anticholinergics (including over-the-counter antihistamines or medications for overactive bladder), tricyclic antidepressants, tobacco, and alcohol can cause xerostomia and difficulty swallowing. Opioids can reduce esophageal motility. Use of proton pump inhibitors or histamine H2 blockers suggests complications from gastroesophageal reflux disease. “Do you have asthma or any food or environmental allergies?” Positive response should prompt consideration of eosinophilic esophagitis; random biopsies should be obtained during esophagogastroduodenoscopy to evaluate for this diagnosis. |

| Examination component | Physical findings | Potential diagnosis or consideration |

|---|---|---|

| General | ||

| Mental status | Obtunded or intoxicated | Transient and self-limited dysco-ordination of swallow; address underlying causes |

| Nutritional state | Cachexia | Neoplasia |

| Overall fitness | Sarcopenia | Chronic disease |

| Strength | Weakness/fatigability | Myasthenia gravis |

| Integumentary | ||

| Skin inspection | Needle tracks or sores; cold, clammy skin | Substance use or opioid-induced esophageal dysfunction |

| Sausage digits or Raynaud phenomenon | Connective tissue disease (e.g., scleroderma) | |

| Head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat | ||

| Eyes | Ptosis (fatigable), diplopia | ALS |

| Mouth | Cervical or supraclavicular lymphadenopathy | Infectious esophagitis or malignancy |

| Dry mouth (xerostomia) | Connective tissue disease, medication adverse effect, or tobacco use | |

| Poor dentition, poorly fitting dentures | Inability to comfortably or effectively form a food bolus precludes safe deglutition | |

| Thyromegaly or goiter | Extrinsic esophageal compression | |

| Tongue deviates, tongue fasciculations | ALS or cranial nerve defects | |

| Observe a swallow | Coughing, choking, or drooling | Drooling and nasopharyngeal regurgitation suggest oropharyngeal localization; coughing confirms an aspiration risk |

| Speech | Weak or breathy voice, dysarthria | Vocal cord pathology or ALS |

| “Wet” voice | Laryngeal aspiration (likely chronic) | |

| Abdominal | ||

| Inspection | Signs of portal hypertension (e.g., varicosities, jaundice, distension) | Esophageal varices causing dysphagia by mass effect and peristalsis disruption |

| Palpation and percussion | Organomegaly | Malignancy |

| Neurologic | ||

| Cranial nerves | Absent gag reflex | Cranial nerves IX and X affected |

| Asymmetric facial motor findings | Cranial nerves V, VII, and XII share sensory and motor control over the muscles of expression and the tongue | |

| Gait | Abnormal gait | Weakness generalizes to swallowing |

Most patients with dysphagia have esophageal dysfunction caused by benign and self-limited conditions, including functional esophageal disorders.1 Oropharyngeal symptoms, particularly in patients without known comorbidities, are more worrisome; they may be the initial presentation of malignancy or neurodegenerative illness.9

GLOBUS PHARYNGEUS

Globus pharyngeus, an intermittent nonpainful sensation of a lump, foreign body, or phlegm in the neck or throat, should be distinguished from dysphagia. Globus pharyngeus has a benign natural course, typically improves with swallowing, and generally does not require further evaluation beyond a careful history and examination. It is commonly associated with GERD or anxiety.23

SYMPTOMS AND HISTORY

Patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia often report choking, coughing, drooling, nasal regurgitation, difficulty initiating a swallow, or needing repeated swallows to clear food from the mouth. They may have hoarseness or other voice changes, including a “wet” voice. Patients will usually accurately localize their symptoms to the throat or neck.

Patients with esophageal dysfunction typically do not have difficulty initiating a swallow, but report a sensation of food getting stuck after swallowing. Patients with obstructive lesions report progressive symptoms occurring mainly with solids, whereas those with motility disorders often have intermittent dysphagia with solids and liquids.

Regurgitation of undigested food, particularly at night, is characteristic of achalasia or Zenker diverticulum. Painful swallowing (odynophagia) suggests an infectious process such as esophageal candidiasis or viral esophagitis. Distal esophageal spasm may also cause pain with swallowing, but this condition is much less prevalent.24

RISK ASSESSMENT

Patients with dysphagia who also report weight loss, fever, gastrointestinal bleeding, or odynophagia, or who have unusually severe or rapidly progressive symptoms, especially older adults and those with a history of cancer or surgery, should have a more comprehensive expedited evaluation. In addition to esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and barium esophagography, the evaluation may include laryngoscopy to check for pharyngeal lesions and computed tomography to detect extrinsic masses.9,25

Isolated dysphagia does not necessarily require immediate testing. Patients younger than 50 years are considered low risk, particularly if they have had intermittent symptoms of GERD or dyspepsia for more than six months. Testing may be safely deferred in these patients pending a treatment trial, such as a four-week course of a proton pump inhibitor.9,26,27

Patients with oropharyngeal symptoms, hoarseness, or coughing provoked by swallowing sips of water must be evaluated for malignancy and other obstructive lesions, as well as aspiration risk. They should be referred to an otorhinolaryngologist or an appropriately trained speech-language pathologist for further imaging or formal swallowing studies.9 The specific screening instruments and tests used, as well as the health professionals administering them, vary based on local practice, expertise, and resources.

Patients with persistent symptoms and a negative oropharyngeal evaluation should be referred for EGD to rule out esophageal pathology.28 Because of overlapping sensory innervation, the actual level of obstruction may be lower than perceived by the patient; in up to one-third of cases, symptoms in the throat or neck are caused by lesions in the distal esophagus.28

Esophageal Dysphagia

TESTING

EGD is the recommended initial test for patients with suspected esophageal dysphagia, followed by barium esophagography if EGD findings are negative.9,29,30 EGD directly visualizes the esophageal lumen and mucosa; can detect obstructive lesions, infections, inflammatory conditions, and reflux esophagitis; allows for stricture dilatation and biopsy; and is generally more cost-effective than barium esophagography. However, barium esophagography is preferred over EGD for detecting subtle narrowing or esophageal webs that may be amenable to dilatation, as well as extrinsic compression of the esophagus. Patients on anticoagulant therapy should undergo barium esophagography first to determine whether a dilatation procedure is needed, which requires stopping anticoagulant therapy. However, routine biopsies can generally be done in these patients without discontinuing therapy.31

For accurate diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis, biopsies from the midthoracic and distal esophagus, even if the mucosa appears to be normal, should be requested for all patients with unexplained dysphagia.15,17 Although the endoscopist or radiologist may suspect achalasia or a hypercontractile motility disorder based on EGD or barium esophagography findings,32 high-resolution esophageal manometry is required to definitively diagnose these conditions.33,34

AVOIDING OVERDIAGNOSIS

Recent research has suggested that although high-resolution esophageal manometry is important for the diagnosis of achalasia, it may result in overdiagnosis of esophageal motility disorders and lead to overtreatment with invasive endoscopic therapies.35 Many patients who are thought to have hypercontractile motility disorders may actually have functional esophageal symptoms unrelated to manometric findings.36 Testing for these uncommon motility disorders can be safely deferred for at least a few months to allow for a trial of optimal medical management of more common conditions. Delayed diagnosis of achalasia does not increase the risk of esophageal cancer.37

INITIAL TREATMENT

Patients with GERD symptoms, esophagitis, or peptic stricture should undergo acid suppression therapy with standard doses of proton pump inhibitors for eight to 12 weeks.38,39 Patients with eosinophilic esophagitis may also respond to this regimen, but most require elimination diets, topical steroids, or both.40,41

For patients with functional dysphagia, functional chest pain, heartburn, or globus pharyngeus, reassurance about the benign and self-limited nature of these conditions, mindful eating, avoidance of trigger foods or situations, and a trial of acid suppression may be helpful. Tricyclic anti-depressants, which modulate esophageal visceral hypersensitivity and hypervigilance, are somewhat effective in reducing symptoms.19 The dosages used in dyspepsia trials were 25 mg of amitriptyline or 50 mg of imipramine per day.42 Cognitive behavior therapy is helpful in patients with functional dyspepsia27 and may be considered if medical therapy is ineffective.19

Oropharyngeal Dysphagia

Up to one-half of debilitated and frail older adults have some degree of dysphagia and silent aspiration, although they often are not aware of the problem. Patients who have had a stroke and those with Parkinson disease, dementia, or sarcopenia are at particular risk.11,12 Dysphagia may be considered a geriatric syndrome. It is multifactorial and may be triggered by acute insults or gradual decline; it leads to poor outcomes such as malnutrition, social isolation, dehydration, weight loss, and aspiration pneumonia; and treatment requires multidisciplinary interventions.43

SCREENING

Although hospitalized patients are routinely assessed for dysphagia, particularly after a stroke, impairments in community-dwelling older adults may not be recognized. All patients with chronic illness or recent pneumonia should be periodically screened for dysphagia.43 The single question “What about swallowing?” may be as effective as more detailed screening tools.22 Patients who are sufficiently alert and able to follow directions may also be observed swallowing a few sips of water.

AVOIDING OVERTREATMENT

In older patients with progressive chronic illness, a diagnosis of oropharyngeal dysphagia should prompt a discussion about goals of care. The family physician is well-suited to provide anticipatory guidance about the potential consequences of dysphagia, as well as a realistic assessment of the patient's overall condition and long-term prospects. A formal swallowing evaluation may be needed to guide this discussion (Table 5).22,44–49

| Video fluoroscopic swallowing study (modified barium swallow) Preferred diagnostic test; more accurate than bedside swallow assessment for detection of aspiration and allows for more precise treatment recommendations44,45 Performed by radiologist and speech-language pathologist in video fluoroscopy suite46 Fiber-optic endoscopic evaluation Supplementary tool to video fluoroscopic swallowing study; good correlation in detection of aspiration and bolus residue in the pharynx and pharyngeal-laryngeal area Trial of compensatory maneuvers using different viscosities (thin liquid, thick liquid, puree, solid food) to potentially improve swallowing effectiveness Performed by speech-language pathologist in outpatient/bedside setting with physician review; easy to perform and well tolerated46 Bedside swallow assessment Structured observation of eating and drinking by speech-language pathologist or other trained observer Trial swallows using different viscosities (thin liquid, thick liquid, puree, solid food): check for coughing, choking, “wet” voice, or piecemeal swallowing (i.e., multiple swallows per bolus) Water-swallowing test (5 to 30 mL) or repetitive saliva-swallowing test: check for coughing, choking, or “wet” voice Pulse oximetry combined with trial swallows or water-swallowing test: check for oxygen desaturation > 2% to 3% Patient self-evaluation: selected questionnaires to assess health status, dysphagia severity, and quality of life Eating Assessment Tool47 Single question (“What about swallowing?”) may be as effective as more detailed screening tools22 Swallowing Quality of Life questionnaire48 Sydney Swallow Questionnaire49 |

Interventions for oropharyngeal dysphagia have limited benefit because of the inevitable decline in most patients. Nasogastric tube feeding does not result in any survival benefit or reduce rates of aspiration pneumonia,50,51 and it is associated with significant harms.52,53 Hand feeding is as effective and is generally recommended; caregivers and care settings must promote choice and respect the preferences of patients and their surrogates.54

MULTIDISCIPLINARY EVALUATION AND REHABILITATION

Speech-language pathologists use various tests ranging from bedside assessment to instrumented swallowing studies to determine specific deficits, the patient's potential for improvement, and the most appropriate dietary modifications and swallow therapies. Thickened liquids and foods with specific textures are often helpful in reducing aspiration risk. Patients with the ability to remember and follow instructions may be taught compensatory maneuvers of the head, neck, and chin, as well as rehabilitative exercises to promote safer swallowing (Table 6).22,55–57

| Diet modifications Mindful eating Avoiding foods likely to cause dysphagia Chewing carefully Cutting food into smaller pieces Drinking liquids to dilute food bolus Eating slowly Lubricating with sauces Taking smaller bites Mechanical soft diet to compensate for impaired chewing due to weakness or poor dentition Modified consistency diet to compensate for impaired swallowing (thickened food and liquids with increased viscosity and cohesiveness slow transport speed) Pureed diet to compensate for impaired chewing due to weakness, poor dentition, or dry mouth with impaired bolus formation Tasting diet55 Patient-centered approaches to feeding and environments conducive to eating should be part of usual care for all older adults with chronic debilitating illness22 Swallowing rehabilitation* Muscular reconditioning exercises to strengthen jaw, lips, and tongue In clinically stable patients who have potential for improvement (e.g., after a stroke), the goal is long-term change in control of swallowing via neuroplasticity In patients with progressive conditions (e.g., Parkinson disease), the goal is maintaining current swallowing status as long as possible Compensatory safe-swallow techniques (positioning to compensate for weakness and dysfunction) Eating upright Chin-tuck maneuver for patients with stroke or degenerative disease changes pharyngeal dimensions to direct the food bolus toward the pharynx and esophagus, compensates for delay of glottic closure, and reduces aspiration risk during swallowing56 Head-turn maneuver for patients with unilateral weakness (turning head toward weaker side) uses gravity to push the bolus toward the stronger side57 Enteral feeding† Nasogastric tube feeding: typically placed during the first week after stroke to allow for administration of nutrition and medication Percutaneous endoscopic gastronomy: used longer term if dysphagia persists after the first week; best for patients with some degree of rehabilitation potential; does not improve mortality or reduce aspiration risk |

Palliative care specialists can help facilitate patient-centered feeding. One hospice, in collaboration with professional chefs, maintains a website featuring recipes that have been adapted to emphasize pleasurable textures and tastes.55 Social connections and rituals involving food remain important even when swallowing is no longer possible.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Spieker,13 and by Palmer, et al.2

Data Sources: We searched PubMed and Google Scholar using the following search terms alone and in various combinations: dysphagia, esophageal spasm, gastroesophageal reflux disease, eosinophilic esophagitis, functional esophageal disorders, achalasia, esophageal motility disorder, and aspiration. We examined clinical trials, meta-analyses, review articles, and clinical guidelines, as well as the bibliographies of selected articles. The Cochrane database and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: August 2019 to July 2020.

The authors thank Darlene E. Graner, SLPD, CCC-SLP, and Emily A. Hosfield, MS, CCC-SLP, for their review of the manuscript.