Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(11):663-671

Related Curbside Consultation: Making Recommendations to Reduce Noise Exposure

Patient information: See related handout on tinnitus, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

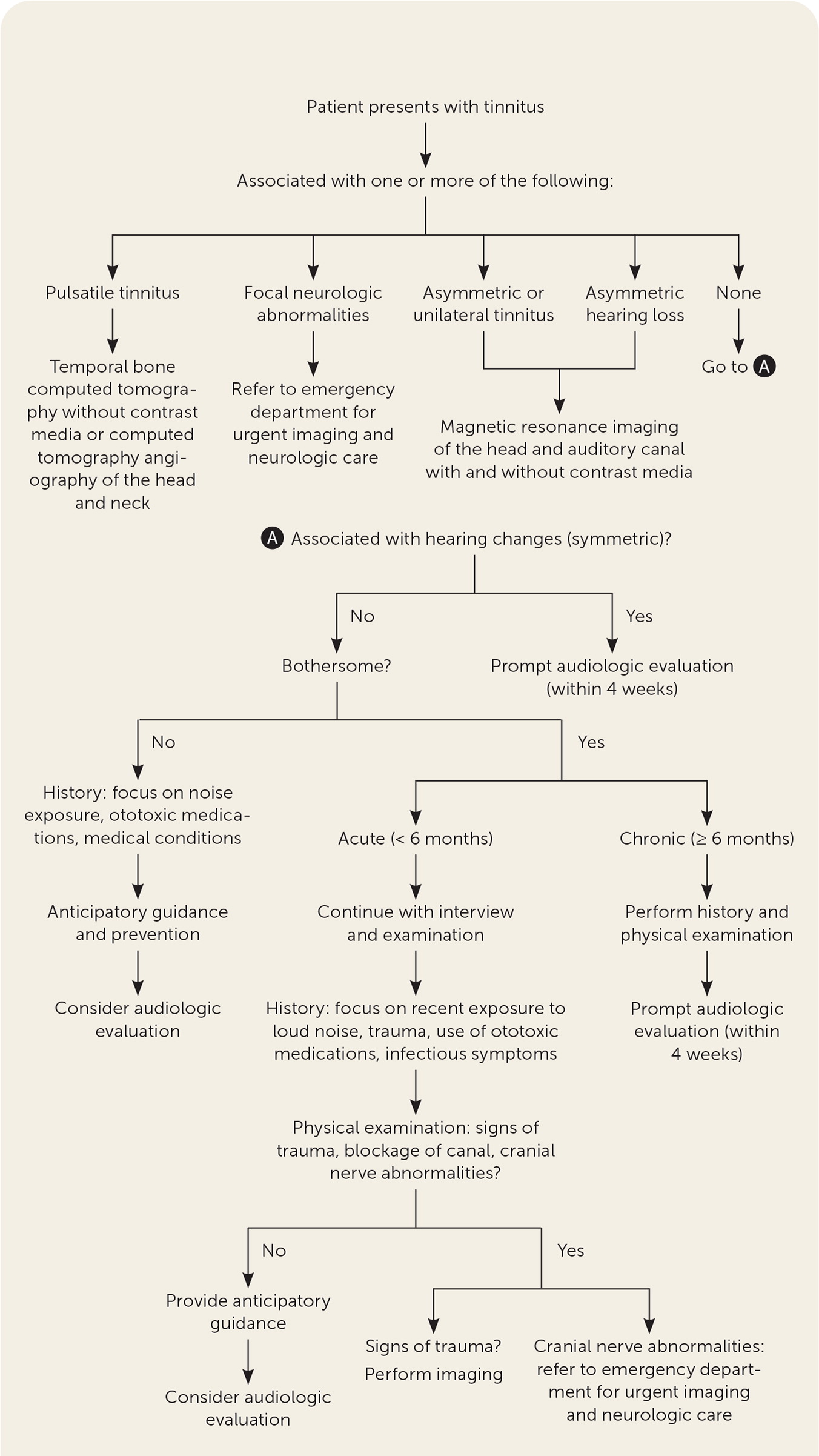

Tinnitus is the sensation of hearing a sound in the absence of an internal or external source and is a common problem encountered in primary care. Most cases of tinnitus are benign and idiopathic and are strongly associated with sensorineural hearing loss. A standard workup begins with a targeted history and physical examination to identify treatable causes and associated symptoms that may improve with treatment. Less common but potentially dangerous causes such as vascular tumors and vestibular schwannoma should be ruled out. A comprehensive audiologic evaluation should be performed for patients who experience unilateral tinnitus, tinnitus that has been present for six months or longer, or that is accompanied by hearing problems. Neuroimaging is not part of the standard workup unless the tinnitus is asymmetric or unilateral, pulsatile, associated with focal neurologic abnormalities, or associated with asymmetric hearing loss. Cognitive behavior therapy is the only treatment that has been shown to improve quality of life in patients with tinnitus. Sound therapy and tinnitus retraining therapy are treatment options, but evidence is inconclusive. Melatonin, antidepressants, and cognitive training may help with sleep disturbance, mood disorders, and cognitive impairments, respectively. Avoidance of noise exposure may help prevent the development or progression of tinnitus. Providing information about the natural progression of tinnitus and being familiar with the causes that warrant additional evaluation, imaging, and specialist involvement are essential to comprehensive care.

Tinnitus is the perception of sound in the absence of an objective internal or external source. Tinnitus is a symptom, not a disease, and although it is typically not associated with a dangerous condition, it can significantly affect quality of life. Tinnitus is a common problem among adults in the United States, with an estimated prevalence of 10% to 15% and peak incidence between 60 and 69 years of age.1–3 At least 20% of people diagnosed with tinnitus will seek clinical intervention.4 The etiology of primary tinnitus is often unclear, but most cases are associated with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). Secondary tinnitus results from sound generated by a source near the ear or referred to the ear, and is rare, accounting for less than 1% of tinnitus cases.5,6 Vascular and neuromuscular etiologies are the more common causes of secondary tinnitus.5,7 Guidelines recommend a standard approach to history and physical examination that can begin the process of determining the etiology of the tinnitus, followed by audiometric testing and imaging, laboratory studies, and other testing as appropriate.8,9

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not order imaging studies in patients with nonpulsatile bilateral tinnitus, symmetric hearing loss, and an otherwise normal history and physical examination. | American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation |

Etiology

For this review, tinnitus is categorized as primary and secondary. Primary tinnitus is the more common of the two categories. It is idiopathic, and most cases are associated with SNHL, including presbycusis and noise-related hearing loss. The exact pathophysiology of primary tinnitus is often unclear and is likely multifactorial. It is thought to be a phantom sensation from abnormal neural activity in the ear, the auditory nerve, or central nervous system.10 Patients with primary tinnitus that is not bothersome do not require further intervention.8 Secondary tinnitus has an identifiable cause.8 Table 1 lists the causes of secondary tinnitus.6,11–16 Many medications are associated with ototoxicity, resulting in tinnitus or hearing loss; the most commonly used are listed in Table 2.17–19 Tinnitus is also a common accompanying symptom of Meniere disease and vestibular schwannoma, previously known as acoustic neuroma. Tinnitus is strongly associated with depression; the presence of tinnitus can worsen depressive symptoms and contribute to suicidal ideation.8,20

| System | Causes |

|---|---|

| Infectious | Bacterial (Lyme disease, syphilis), fungal, viral |

| Metabolic | Diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Neurologic | Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, idiopathic stapedial or tensor tympani muscle spasm, multiple sclerosis, palatal myoclonus, spontaneous intracranial hypotension, type I Chiari malformation, vestibular migraine |

| Otologic | Cerumen impaction, cholesteatoma, foreign body, Meniere disease, middle ear effusion, otitis, otosclerosis, patulous eustachian tube, tympanic membrane perforation, vestibular schwannoma |

| Somatic | Head or neck injury, temporomandibular joint dysfunction |

| Toxicologic | Medication or substance use |

| Traumatic | Cerumen removal |

| Vascular | Arterial bruit; arteriovenous malformation; carotid atherosclerosis, dissection, or tortuosity; Paget disease; vascular tumors; venous hum |

| Anesthetics Bupivacaine (Marcaine), lidocaine Antiepileptics Carbamazepine (Tegretol), pregabalin (Lyrica) Anti-inflammatory agents Aspirin,* nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) Antimalarial agents Chloroquine (Aralen), quinine Antimicrobial agents Aminoglycosides† Amikacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, neomycin, tobramycin (Tobrex) Macrolides Azithromycin (Zithromax), erythromycin‡ Tetracyclines Doxycycline, minocycline (Minocin) Vancomycin§ Antineoplastic agents Platinum compounds Carboplatin (Paraplatin), cisplatin Protein kinase inhibitors Axitinib (Inlyta), dasatinib (Sprycel), imatinib (Gleevec), lapatinib (Tykerb), osimertinib (Tagrisso), ruxolitinib (Jakafi) Pyrimidine analogues Capecitabine (Xeloda) Taxanes Paclitaxel (Taxol) Antivirals for treatment of hepatitis C virus infections Ribavirin (Rebetol), sofosbuvir (Sovaldi), telaprevir (Incivek) Immunosuppressants Calcineurin inhibitors Cyclosporine (Sandimmune) Interferons Monoclonal antibodies Ipilimumab (Yervoy), nivolumab (Opdivo), trastuzumab (Herceptin) Loop diuretics Furosemide (Lasix), torsemide (Demadex)|| Paralytics (for anesthesia) Quaternary ammonium compounds Vecuronium Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors Sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis) Vaccinations HPV Bivalent (HPV-16, HPV-18); quadrivalent (HPV-6, HPV-11, HPV-16, HPV-18) Pneumococcal polysaccharide (Pneumovax) Miscellaneous Atorvastatin (Lipitor), bupropion (Wellbutrin), risedronate (Actonel), varenicline (Chantix) Antiarrhythmics, dopamine agonists, hormone agents, proton pump inhibitors |

Diagnosis

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A focused, detailed history and physical examination are the primary tools for diagnosing tinnitus, distinguishing benign from dangerous causes, and determining potential treatment options.8,9 Initial triage involves identifying characteristics of the patient's tinnitus that warrant urgent evaluation: pulsatile, associated with neurologic abnormalities, asymmetric or unilateral symptoms, and asymmetric hearing loss. Although it is much less common, pulsatile tinnitus should raise suspicion for underlying cardiovascular disease and intracranial vascular abnormality (e.g., vascular tumor), increased intracranial pressure, or neoplasm.11

The four history elements that provide the most helpful guidance for evaluation and management of tinnitus are chronicity, location (unilateral or bilateral), any associated hearing changes, and the impact (bothersome or not bothersome). The patient should be asked about associated symptoms, such as disturbance of sleep and mood and cognitive difficulties, because these negatively affect quality of life and may improve with treatment. Specific components, findings, and implications of the history for tinnitus are listed in Table 3.7,13–16,19,21,22,27–29 The tools used most often in studies to assess the impact of tinnitus on daily living are the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory and the Tinnitus Questionnaire.30,31 A newer validated tool, the Hearing and Tinnitus Survey, is a brief questionnaire that can discern between the burden of tinnitus and hearing loss, which may be useful to the clinician.32

| Historical element | Finding | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Impact (measure using a validated questionnaire, [e.g., Tinnitus Handicap Inventory, Tinnitus Questionnaire]) | Bothersome (causes distress, affects quality of life or functional health status) Not bothersome (no significant effect on quality of life) | Treatment should be directed toward those with bothersome tinnitus only; per AAO-HNS guidelines, patients with tinnitus that is not bothersome do not require intervention beyond education |

| Severity (of impact) | Mild Moderate Severe | Most treatments were studied in the setting of moderate to severe tinnitus symptoms |

| Location | Unilateral | Concern for focal auditory lesions (e.g., vestibular schwannoma,* vascular tumor); perform MRI of the head and auditory canal with and without contrast media |

| Bilateral | More likely to predict a normal MRI result; do not routinely perform imaging unless other concerning features are present | |

| Duration | Acute (< 6 months) | Consider recent noise exposure, trauma, otitis media, or use of ototoxic medications |

| Chronic (≥ 6 months) | Tinnitus that persists longer than 6 months is less likely to resolve spontaneously | |

| Character | Ringing, buzzing, hissing | Characteristic of primary tinnitus; recommend cognitive behavior therapy, consider sound therapy, and adjunctive treatments for secondary symptoms if present (i.e., melatonin for sleep disturbance, antidepressants for mood disturbance) |

| Roaring or loss of low-frequency hearing | Consider Meniere disease†; referral to otolaryngology is indicated | |

| Rhythmic clicking | Consider myoclonus/stapedial or tensor tympani muscle spasm; refer to neurology | |

| Pulsatile | Concern for vascular lesion, intracranial hypertension, or systemic cardiovascular comorbidity; order temporal bone CT without contrast media or CT angiography of the head and neck | |

| Associated findings | Ear drainage, ear pain | Consider infectious, inflammatory, or allergic cause; treat accordingly, and refer to otolaryngology if no resolution after appropriate treatment |

| Vertigo, imbalance | Consider cochlear, retrocochlear, or other central nervous system disorders (e.g., Meniere disease,† vestibular schwannoma,* migraine); order MRI of the head and auditory canal with and without contrast media | |

| Unilateral or asymmetric hearing loss | Unilateral or asymmetric hearing loss can be a presenting symptom for vestibular schwannoma†; order MRI of the head and auditory canal with and without contrast media | |

| Symmetric hearing loss | Refer for comprehensive audiologic examination within 4 weeks | |

| Headache | Consider migraine and treat accordingly | |

| Aggravating factors | Position changes or physical activity | Consider vascular or neurologic cause (spontaneous intracranial hypotension); order temporal bone CT without contrast media or CT angiography of the head and neck |

The physical examination should include the head; eyes; ears; neck; neurologic system, focusing on the cranial nerves and cerebellar function; and the cardiovascular system. Table 4 lists specific examination findings that can assist in determining etiology or directing evaluative steps.11–13,22,23,28,33–35

| Component | Finding | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Ear | Cerumen impaction, cholesteatoma, foreign body, middle ear effusion, otitis externa or media, trauma | Treatment may relieve tinnitus |

| Eye | Papilledema, nystagmus, visual field changes | Sign of increased intracranial pressure, such as idiopathic intracranial hypertension or tumor; consider prompt imaging* and neurologic evaluation |

| Musculoskeletal | Temporomandibular joint tenderness, pain, or crepitus | May indicate temporomandibular joint as the cause of tinnitus; consider dental or otolaryngologic referral |

| Neurologic | Abnormal cerebellar testing (ataxia, dysmetria, or dysdiadochokinesia) Abnormal cranial nerve testing | May indicate stroke, increased likelihood of vestibular schwannoma, or intracranial hyper- or hypotension; consider prompt imaging* and neurologic evaluation |

| Vascular | Detectable bruits over the ear canal or periauricular area, orbits, carotids (neck), or chest | May suggest vascular etiology; consider imaging* and referral based on location of bruit |

| Pulsatile tinnitus that changes with light pressure to ipsilateral jugular vein | May indicate venous source of pulsatile tinnitus; imaging* is indicated in pulsatile tinnitus |

AUDIOLOGY

Referral for a comprehensive audiologic examination is appropriate for any patient with tinnitus, regardless of duration or characteristics.8 For patients with chronic tinnitus (i.e., lasting six months or longer), unilateral tinnitus, or any reported hearing changes, the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) guideline recommends referral for comprehensive audiologic examination within four weeks.8,27 Audiometry can identify the presence, degree, nature (i.e., conductive, sensorineural, or mixed), and any asymmetry of hearing loss.8,27

Patients presenting with tinnitus associated with sudden SNHL should have urgent audiometry as recommended by the AAO-HNS guidelines because this requires urgent treatment with intratympanic corticosteroids. If audiometry is not available immediately, it should be performed within two weeks.8

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

The AAO-HNS and European guidelines recommend imaging studies for patients with tinnitus that is unilateral, pulsatile, associated with asymmetric hearing loss, or associated with focal neurologic abnormalities.8,9 This recommendation is based on observational studies that reviewed the high cost, risk of harm, and low yield of these studies outside of the findings mentioned previously on history and physical examination.8

The recommended imaging test to evaluate asymmetric or unilateral, nonpulsatile tinnitus is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and auditory canal with and without contrast media.24 This is the preferred test to evaluate for vestibular schwannoma, the most common cerebellopontine angle lesion, and masses of the auditory pathway. If access to MRI is limited or MRI with contrast media is contraindicated, other options include noncontrast MRI, the auditory brainstem response test, and computed tomography (CT). Noncontrast MRI of the brain is comparably sensitive for evaluating for vestibular schwannoma but may be less appropriate for identifying other causes of tinnitus. The auditory brainstem response test also can be used to screen for vestibular schwannoma and has a high sensitivity for lesions larger than 1 cm, but not for smaller lesions.36 CT may evaluate vascular or osseous lesions but may miss small masses that could contribute to symptoms.24

A temporal-bone CT without contrast media or CT angiography of the head and neck is the recommended study for pulsatile tinnitus. A temporal-bone CT without contrast media specifically evaluates for paragangliomas or adenomatous middle ear tumors.24 CT angiography of the head and neck evaluates for an underlying vascular process, such as carotid stenosis, dural arteriovenous fistulas, or signs of spontaneous or idiopathic intracranial hypertension, among other causes of pulsatile tinnitus.24,37 Noncontrast MRI and magnetic resonance angiography can also be used to evaluate vascular processes if iodinated, or gadolinium contrast media cannot be used. Ultrasonography can be used to evaluate extracranial carotid stenosis, but positive findings are typically followed by CT angiography or magnetic resonance angiography.24

Laboratory test results are unlikely to show a cause for tinnitus, and testing should be guided by clinical suspicion for specific contributing conditions. Previously described links between tinnitus and thyroid disease, vitamin B12 deficiency, and diabetes mellitus were based on very low-quality evidence; therefore, routine testing for such disease entities is not warranted.3,38–41 If the clinician is concerned about syphilis or Lyme disease, low-quality evidence suggests that appropriate serologies may be helpful; however, the incidence is low.42

Prevention

Tinnitus is strongly associated with SNHL; therefore, measures to prevent occupational and recreational noise exposure may be beneficial. Earplugs and earmuffs have been shown to reduce noise-related hearing loss.43 Caution with potentially ototoxic medications and monitoring during use may help prevent tinnitus or its progression.17–19

Treatment

Treatment of tinnitus should focus on an underlying cause when identified, as in the case of secondary tinnitus. The following treatment options are for chronic, bothersome, primary tinnitus, and focus on alleviating or reducing the severity of patient distress and conditions associated with tinnitus (Table 58,9,20,25,27,44–64). Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) is the only treatment with moderate- to high-quality evidence to suggest benefit on the primary tinnitus outcome,8,9,25,44,45 often referred to as tinnitus distress, per measurement by a patient self-reporting survey such as the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory or Tinnitus Questionnaire. Conditions associated with tinnitus typically include mood and cognitive disorders, sleep problems, and general disability.

| Treatments to consider for tinnitus Cognitive behavior therapy (moderate- to high-quality evidence) Sound therapy (low-quality evidence) Acoustic stimulation Hearing aids Sound/noise generation Tinnitus retraining therapy (very low-quality evidence) Treatments to consider for tinnitus-associated conditions Antidepressants Nortriptyline (Pamelor; depression) Sertraline (Zoloft; anxiety) Trazodone (sleep disturbance) Tricyclic antidepressants (disability) Cognitive training (attention, concentration, memory) Melatonin (sleep disturbance) Treatments to avoid Benzodiazepines Clonazepam (Klonopin) Anticonvulsants Acamprosate (Campral) Carbamazepine (Tegretol) Gabapentin (Neurontin) Lamotrigine (Lamictal) Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation Electrical stimulation Transcranial direct current stimulation Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation Bimodal stimulation Microvascular decompression (surgical procedure) Ginkgo biloba Nitrous oxide Hyperbaric oxygen Acupuncture |

TREATMENTS TO CONSIDER

CBT is the only effective treatment for tinnitus with a well-established, moderate- to high-quality evidence base. CBT mitigates the effects of tinnitus by helping patients develop alternative coping strategies. The major effect of CBT on tinnitus is the improvement of quality of life. Methods include in-person, group or individual, and internet-based CBT; however, in-person CBT may have a larger positive effect on tinnitus symptoms.8,9,25,44,45

Sound therapy is recommended by the AAO-HNS for the treatment of tinnitus by masking the sound through acoustic stimulation, hearing aids, or sound generators, thereby allowing the auditory system to adapt. The evidence for sound therapy as an effective solo treatment is inconclusive, but there have been no associated adverse effects.25,46,47 Health professionals can consider sound therapy, by itself or with other treatments, for patients with chronic tinnitus. Tinnitus retraining therapy, a combination of sound therapy and directed counseling, is recommended by otolaryngologists but lacks supportive evidence.45,48–50

There are effective treatments for several conditions associated with tinnitus, including depression, anxiety, sleep disturbance, cognition, and general disability. Nortriptyline (Pamelor) and sertraline (Zoloft) were found to improve comorbid depression and anxiety, respectively. Tri-cyclic antidepressants may improve tinnitus-related disability.51 Trazodone and melatonin were found to improve sleep disturbance associated with tinnitus.52 Cognitive training therapy may help improve the common cognitive impairments related to the condition, specifically attention and concentration.53

TREATMENTS TO AVOID

Benzodiazepines are not recommended for the treatment of tinnitus.2 As a class, benzodiazepines show inconsistent effects, and their use is associated with high rates of adverse effects and potential for abuse.54 Anticonvulsants, including gabapentin (Neurontin), carbamazepine (Tegretol), lamotrigine (Lamictal), and acamprosate (Campral), have been studied on a small scale and found to be ineffective in the treatment of tinnitus with a high rate of adverse effects (18%).20,55 There is no evidence that Ginkgo biloba effectively treats patients with primary tinnitus.56 Nitrous oxide was also found to be an ineffective treatment.57

The use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of tinnitus has been debated. The most recent data showed repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to be ineffective, and it is not recommended for treatment of tinnitus.58 Electrical stimulation, primarily transcranial direct current stimulation, is also ineffective and therefore not recommended.59

The following treatments have been studied, and there is insufficient evidence for or against their use for the treatment of tinnitus: acupuncture60; electrical stimulation in the form of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation61; bimodal stimulation, a combination of auditory and somatosensory (electrical) stimulation62; hyperbaric oxygen63; and a surgical procedure called microvascular decompression of the cranial nerve VIII (vestibulocochlear).64

Anticipatory Guidance for Primary Tinnitus

Resolution or significant reduction in tinnitus can occasionally occur, although this is more likely in younger patients and those with tinnitus of shorter duration, whereas others may develop worse symptoms.26,27 Providing this information may help patients understand the natural course of tinnitus. Counseling patients to avoid loud noise exposure and initiating CBT early in the course may minimize the effect of tinnitus on quality of life and help patients develop coping skills that may reduce the impact of the condition.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Yew65 and Crummer and Hassan.66

Data Sources: A search of Essential Evidence Plus was completed using the key word tinnitus. The search included InfoPOEMs, Cochrane reviews, and practice guidelines. Also searched were DynaMed, PubMed, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration website for specific information about diagnosis, treatment, and other management, including medications associated with tinnitus. Search dates: January 3 to July 31, 2020, and November 24, 2020.