Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(2):164-170

Patient information: See related handout on painful menstrual periods, written by authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

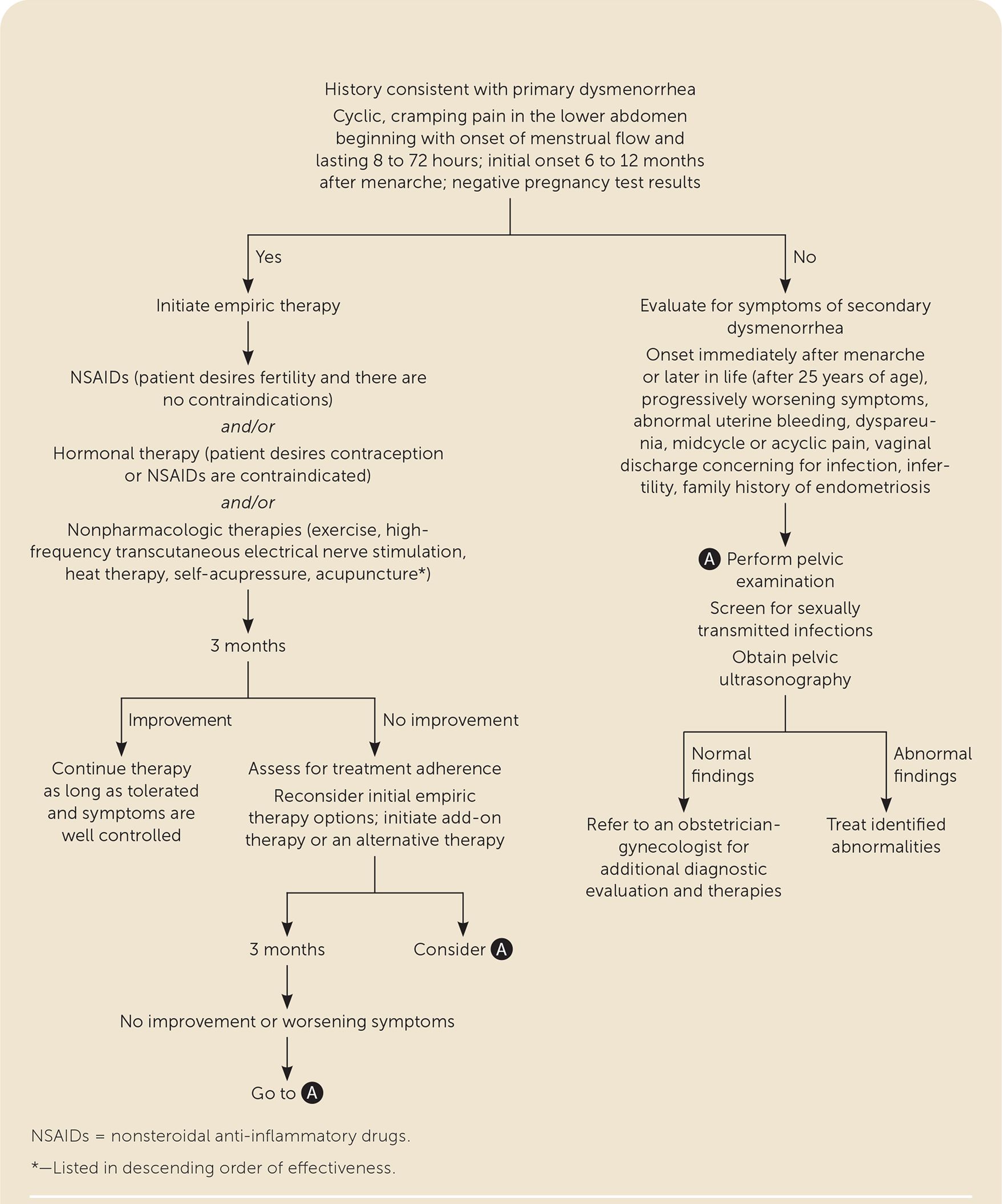

Dysmenorrhea is common and usually independent of, rather than secondary to, pelvic pathology. Dysmenorrhea occurs in 50% to 90% of adolescent girls and women of reproductive age and is a leading cause of absenteeism. Secondary dysmenorrhea as a result of endometriosis, pelvic anatomic abnormalities, or infection may present with progressive worsening of pain, abnormal uterine bleeding, vaginal discharge, or dyspareunia. Initial workup should include a menstrual history and pregnancy test for patients who are sexually active. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hormonal contraceptives are first-line medical options that may be used independently or in combination. Because most progestin or estrogen-progestin combinations are effective, secondary indications, such as contraception, should be considered. Good evidence supports the effectiveness of some nonpharmacologic options, including exercise, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, heat therapy, and self-acupressure. If secondary dysmenorrhea is suspected, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or hormonal therapies may be effective, but further workup should include pelvic examination and ultrasonography. Referral to an obstetrician-gynecologist may be warranted for further evaluation and treatment.

Dysmenorrhea, which is defined as painful menstruation, affects up to 50% to 90% of adolescent girls and women of reproductive age.1,2 Nearly one-half of patients (45%) with symptoms of dysmenorrhea will present first to their primary care physician.3 Dysmenorrhea leads to decreased quality of life, absenteeism, and increased risk of depression and anxiety.4,5 Up to one-half of patients with dysmenorrhea miss school or work at least once, and 10% to 15% have regular absences during menses.6–8 A prospective longitudinal study of 400 patients with dysmenorrhea revealed that most have persistent symptoms throughout their years of menstruation, although some improvement in severity may occur, for example, after childbirth.9

Secondary dysmenorrhea is due to pelvic pathology or a recognized medical condition and accounts for about 10% of cases of dysmenorrhea.1 The most common etiology is endometriosis. Other etiologies include congenital or acquired obstructive and nonobstructive anatomic abnormalities (e.g., müllerian malformations, uterine leiomyomas, adenomyosis), pelvic masses, and infection1 (Table 11,11).

| Diagnosis* | Characteristic signs and symptoms |

|---|---|

| Endometriosis | Infertility; pain with intercourse, urination, or bowel movements |

| Ovarian cysts | Sudden onset and resolution; if twisted, can cause ovarian torsion |

| Uterine polyps | Irregular vaginal bleeding |

| Uterine leiomyomas | Heavy, prolonged periods; constipation or difficulty emptying the bladder possible; more common in older people |

| Adenomyosis | Heavy bleeding, blood clots, pain with intercourse, abdominal tenderness; more common in older people |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | Abdominal pain, fever, vaginal discharge and odor, pain with intercourse, bleeding after intercourse |

| Congenital obstructive müllerian malformations | Amenorrhea, infertility, miscarriage |

| Pelvic adhesions | History of surgery, infertility, bowel obstruction, painful bowel movements, pain with change in position |

| Pelvic masses | Bloating, frequent urination, nausea |

| Cervical stenosis | Amenorrhea, infertility |

Risk Factors

Age younger than 30 years, body mass index less than 20 kg per m2, smoking, earlier menarche (younger than 12 years), longer menstrual cycles, heavy menstrual flow, and history of sexual abuse increase the risk of primary dysmenorrhea. Nulliparity, premenstrual syndrome, and a history of pelvic inflammatory disease are also associated with the disorder. Protective factors include increasing age, increasing parity, exercise, and oral contraceptive use.9,12

Clinical Presentation

Dysmenorrhea is typically described as cramping pain in the lower abdomen beginning at the onset of menstrual flow and lasting eight to 72 hours.15 It is often accompanied by nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, muscle cramps, low back pain, fatigue, and, in more severe cases, sleep disturbance.1,6 In a study of more than 400 patients with dysmenorrhea, 47% reported moderate pain, and 17% reported severe pain on a 0 to 10 visual analog scale.16

Primary dysmenorrhea begins an average of six to 12 months following menarche, corresponding with the initiation of ovulatory cycles, and tends to recur with every menstrual cycle.1

Diagnosis

Evaluation should begin with a complete medical, gynecologic, menstrual, family, and surgical history.1 The history should characterize whether pain coincides with menstruation and include which nonprescription therapies the patient has tried. A family history of similar symptoms may suggest endometriosis, and a history of pelvic surgery may suggest adhesions.1 Symptoms should be carefully elicited because many patients assume pain is a normal part of menstruation.8,17 In a study of more than 4,300 patients seeking care for symptoms of dysmenorrhea, nearly two-thirds were told nothing was wrong; this was even more likely when symptoms began during adolescence. 3 A substantial delay from symptom onset to diagnosis is common, ranging from 5.4 years in adolescents to 1.9 years in adults.3 In secondary dysmenorrhea, the time from onset of symptoms to surgically confirmed diagnosis may range from four to 11 years.18

A pelvic examination is not necessary in patients presenting with symptoms consistent with primary dysmenorrhea (Figure 1). Pregnancy should be ruled out in patients who are sexually active. If symptoms consistent with secondary dysmenorrhea are reported, a pelvic examination should be completed and ultrasonography performed to assess for anatomic abnormalities or other pathology 1 (Table 11,11).

Treatment

NSAIDS

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which have been shown to be superior to both placebo and acetaminophen, are a first-line therapy for primary dysmenorrhea. NSAIDs act by reducing prostaglandin production.20,21 NSAIDs should be initiated one to two days before the onset of menses and continued in regular dosing intervals through the first two to three days of bleeding, correlating with the highest levels of prostaglandins.21 There is no difference between individual NSAIDs, including cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, for pain relief or safety.19,22 Commonly prescribed NSAIDs include ibuprofen (800 mg initially, followed by 400 to 800 mg every eight hours) and naproxen (500 mg initially, followed by 250 to 500 mg every 12 hours)21; both medications can be purchased over the counter, often for less than $10 per month. NSAIDs can also have a secondary benefit of reducing heavy menstrual bleeding.20

Despite the known effectiveness of NSAIDs in the treatment of dysmenorrhea, nearly 20% of patients report minimal to no relief.10 This is likely multifactorial. Up to 25% to 50% of patients do not take the correct dosage to provide adequate relief.10 Variance in menstrual cycles may prevent appropriate timing of treatment. NSAIDS are also associated with adverse effects, including indigestion, headaches, and drowsiness, which may limit use.22 Taking NSAIDs with food reduces gastrointestinal adverse effects.

HORMONAL THERAPY

Hormonal therapy is also considered a first-line treatment for dysmenorrhea and can be added or used as an alternative to NSAID therapy in patients who are not planning to become pregnant.1,10 Hormonal therapies improve symptoms of dysmenorrhea by thinning the endometrial lining and reducing cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin production.10 Hormonal therapies may also have secondary benefits, including improvement of heavy menstrual bleeding,23 premenstrual mood,24 acne or hirsutism, and bone mineral density, and decreased risk of endometrial, ovarian, and colorectal cancers.25

Combined estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives are effective in adolescents and adults with primary dysmenorrhea, leading to significant improvement in pain and decreased frequency and dose of analgesics.26,27 There is no difference in effectiveness between low- and medium-dose estrogen preparations.27 Commonly reported adverse effects of combined oral contraceptives include nausea, headaches, and weight gain.27 Continuous combined oral contraceptive regimens with more than 28 days of active hormone may lead to improved and more rapid pain relief but are associated with more weight gain than cyclic regimens.28–30 Progestin-only oral contraceptives are an alternative for those who are not candidates for estrogen therapy. Continuous norethindrone (5 mg daily) is as effective as cyclic combined oral contraceptives for the treatment of dysmenorrhea,2 although this dosing is not currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a contraceptive.1

Other hormonal contraceptives are also acceptable for the management of dysmenorrhea, including transdermal patches, vaginal rings, progestin implants, intramuscular or subcutaneous medroxyprogesterone depot injection (Depo-Provera), and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena).1,25 A systematic review found that the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system is as effective as, if not superior to, oral contraceptives in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea and secondary dysmenorrhea caused by endometriosis.31 Physicians and patients must weigh secondary benefits with contraindications, U.S. Food and Drug Administration boxed warnings, and adverse effects when considering hormonal treatment options.

NONPHARMACOLOGIC THERAPIES

Nonpharmacologic therapies and integrative modalities can complement first-line medical therapy or be used as alternatives when first-line interventions are contraindicated or declined.

Physical activity reduces intensity and duration of pain in primary dysmenorrhea.32 Based on a Cochrane review, exercise—regardless of intensity but with the goal of achieving 45 to 60 minute intervals at least three times per week—may significantly reduce menstrual pain that is associated with moderate to severe dysmenorrhea.33 Exercise may not reduce overall menstrual flow or pain intensity as effectively as NSAIDs, but given its many benefits beyond managing dysmenorrhea, it should be reviewed with patients as a treatment option.33

High-frequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation is effective for pain reduction in primary dysmenorrhea, with improvement in reported pain level, duration of pain relief, and decreased use of analgesics compared with sham transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation.34,35 A small randomized controlled study found heat therapy to be effective in improving menstrual pain.36

Self-acupressure, a safe and low-risk intervention, can significantly reduce average menstrual pain intensity, number of days with pain, and use of analgesics over a three-month period37 but is not superior to NSAIDs.38 Manual acupuncture and electroacupuncture are effective at reducing menstrual pain compared with no treatment,39 although they may be no better than sham acupuncture.38,40 No evidence supports the use of spinal manipulation to treat dysmenorrhea.41

Behavioral interventions and pain management training, such as progressive muscle relaxation, imagery, and biofeedback, that focus on coping strategies may help with spasmodic-type pain.42 However, studies were small and of poor methodological quality.

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of the dietary supplements fenugreek, fish oil, ginger, valerian, vitamin B1, Zataria multiflora, and zinc sulfate for dysmenorrhea43 or the use of antioxidants for endometriosis-related pelvic pain.44 A small systematic review found that the herbal therapy fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) may be as effective as NSAID therapy in reducing menstrual pain in primary dysmenorrhea, although the quality of evidence was considered low.45 Small studies have found improvement in dysmenorrhea pain with the use of Chinese herbal medicines, but these studies should be interpreted with caution given poor methodological quality and inconsistencies in formulations.46,47

Treatment Resistance

If symptoms persist despite three to six months of empiric treatment or if at any time the symptom pattern suggests a secondary etiology, a more extensive workup should be performed for secondary causes of dysmenorrhea (Figure 1). A comprehensive history and physical examination should evaluate for causes of chronic pelvic pain, including gastroenterologic, urologic, musculoskeletal, or psychosocial etiologies.1 Workup for secondary dysmenorrhea should also include a pelvic examination and ultrasonography.1,19 Normal findings do not rule out endometriosis, which is a surgical and pathologic diagnosis. Referral to an obstetrician-gynecologist may be indicated for diagnostic evaluation, including advanced imaging or laparoscopy.1,19

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues, such as elagolix (Orilissa) or leuprolide (Lupron), used for at least six months with add-back replacement estrogen therapy have been used for treatment of surgically confirmed endometriosis; studies demonstrate up to a 75% reduction of dysmenorrhea symptoms.1,10,48 Adverse effects may include hot flashes, headaches, and hyperlipidemia, which improve with discontinuation of treatment.48 Aromatase inhibitors also require add-back estrogen therapy, and further research is needed to support their effectiveness.10 Alternative treatments, including beta-2 adrenoceptor agonists,49 calcium channel blockers, and vasodilators,10 have the potential to reduce menstrual pain in patients unresponsive to first-line therapies but are often limited by intolerable adverse effects.

Surgical options are available for patients whose symptoms do not improve with medical therapies. Laparoscopy is used diagnostically and therapeutically for endometriosis.1 Laparoscopic presacral neurectomy has been found to be more effective than laparoscopic uterosacral nerve ablation for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.50 However, a systematic review and a large randomized controlled trial found insufficient evidence to routinely recommend either procedure.50,51 If hysterectomy is performed, pain reduction is similar between total and supracervical laparoscopic hysterectomy.52

Data Sources: We searched Essential Evidence Plus, PubMed, POEMs, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines. Key words were dysmenorrhea combined with systematic reviews, clinical decision rules, prevention, natural history, prognosis, diagnosis, and therapy. Search dates: January 2020, May to June 2020, October 2020, and February 2021.

Editor's Note: Dr. Fogleman is an assistant medical editor for AFP.