Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(4):425-428

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Key Points for Practice

• In newborns who do not require resuscitation, delaying cord clamping for more than 30 seconds reduces anemia, especially in preterm infants.

• No type of routine suctioning is helpful, even for nonvigorous newborns delivered through meconium-stained amniotic fluid.

• If resuscitation is required, heart rate should be monitored by electrocardiography as early as possible.

• Positive-pressure ventilation should be started in newborns who are gasping, apneic, or with a heart rate below 100 beats per minute by 60 seconds of life.

From the AFP Editors

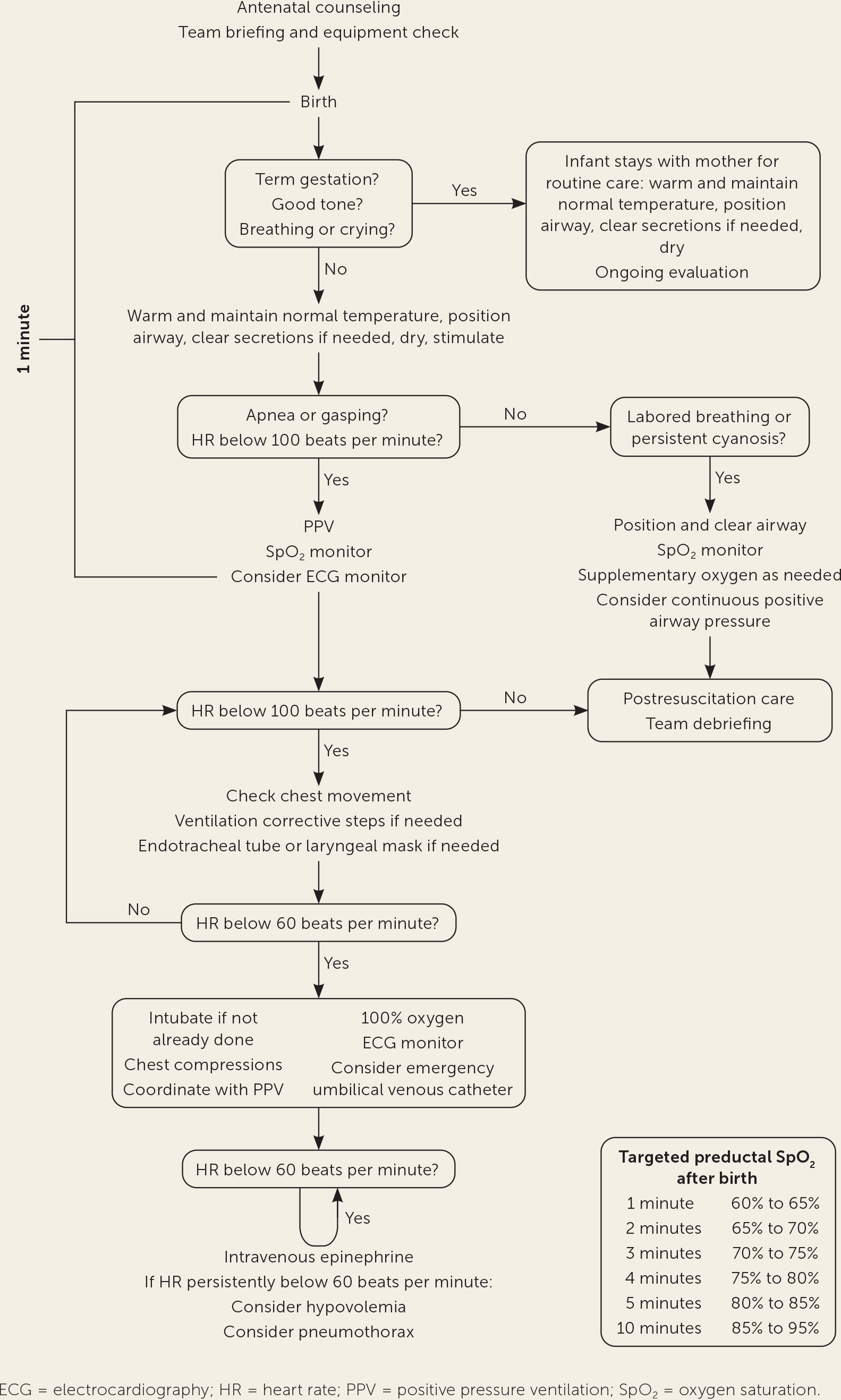

Approximately 10% of infants require help to begin breathing at birth, and 1% need intensive resuscitation. The American Heart Association released minor updates to neonatal resuscitation recommendations with only minor changes to the previous algorithm (Figure 1).

Anticipation of Resuscitation

Every birth should be attended by one person who is assigned, trained, and equipped to initiate resuscitation and deliver positive pressure ventilation. Additional personnel are necessary if risk factors for complicated resuscitation are present. Equipment checklists, role assignments, and team briefings improve resuscitation performance and outcomes.

Care of the Well Newborn

Early skin-to-skin contact benefits healthy newborns who do not require resuscitation by promoting breastfeeding and temperature stability. Term newborns with good muscle tone who are breathing or crying should be brought to their mother's chest routinely. Routine suctioning, whether oral, nasal, oropharyngeal, or endotracheal, is not recommended because of a lack of benefit and risk of bradycardia.

Delaying cord clamping for more than 30 seconds is reasonable for term and preterm infants who do not require resuscitation. In term infants, delaying clamping increases hematocrit and iron levels without increasing rates of phototherapy for hyperbilirubinemia, neonatal intensive care, or mortality. In preterm infants, delaying clamping reduces the need for vasopressors or transfusions. Cord milking in preterm infants should be avoided because of increased risk of intraventricular hemorrhage.

Initial Resuscitative Actions

Preterm and term newborns without good muscle tone or without breathing and crying should be brought to the radiant warmer for resuscitation. Newborn temperature should be maintained between 97.7°F and 99.5°F (36.5°C and 37.5°C), because mortality and morbidity increase with hypothermia, especially in preterm and low birth weight infants.

According to the recommendations, suctioning is only necessary if the airway appears obstructed by fluid. For nonvigorous newborns with meconium-stained fluid, endotracheal suctioning is indicated only if obstruction limits positive pressure ventilation, because suctioning does not improve outcomes.

Tactile stimulation is reasonable in newborns with ineffective respiratory effort, but should be limited to drying the infant and rubbing the back and the soles of the feet.

Heart rate assessment is best performed by auscultation. If resuscitation is required, electrocardiography should be used, especially with chest compressions. Electrocardiography detects the heart rate faster and more accurately than a pulse oximeter.

Ventilation and Oxygen Support

Positive pressure ventilation should be delivered without delay to infants who are apneic, gasping, or have a heart rate below 100 beats per minute within the first 60 seconds of life despite initial resuscitation. For every 30 seconds that ventilation is delayed, the risk of prolonged admission or death increases by 16%. Positive pressure ventilation should be provided at 40 to 60 inflations per minute with peak inflation pressures up to 30 cm of water in term newborns and 20 to 25 cm of water in preterm infants. Positive end-expiratory pressure of up to 5 cm of water may be used to maintain lung volumes based on low-quality evidence of reduced mortality in preterm infants.

For newborns who are breathing, continuous positive airway pressure can help with labored breathing or persistent cyanosis. In preterm infants younger than 30 weeks' gestation, continuous positive airway pressure instead of intubation reduces bronchopulmonary dysplasia or death with a number needed to treat of 25.

In newborns born at 35 weeks' gestation or later, resuscitation starting with 21% oxygen reduces short-term mortality. In newborns born before 35 weeks' gestation, oxygen concentrations above 50% are no more effective than lower concentrations. To start, 21% to 30% oxygen should be used in these newborns, titrating up based on oxygen saturation.

Chest Compressions

If the heart rate remains below 60 beats per minute despite 30 seconds of adequate positive pressure ventilation, chest compressions should be initiated with a two-thumb encircling technique at a 3:1 compression-to-ventilation ratio. Ventilation should be optimized before starting chest compressions, possibly including endotracheal intubation. High oxygen concentrations are recommended during chest compressions based on expert opinion.

Intravascular Access and Interventions

Umbilical venous catheterization is the recommended vascular access, although it has not been studied. Intraosseous needles are reasonable, but local complications have been reported.

Epinephrine is indicated if the heart rate remains below 60 beats per minute despite 60 seconds of chest compressions and adequate ventilation. Intravenous epinephrine is preferred because plasma epinephrine levels increase much faster than with endotracheal administration. Epinephrine should be administered intravenously at 0.01 to 0.03 mg per kg or by endotracheal tube at 0.05 to 0.1 mg per kg. Epinephrine dosing may be repeated every three to five minutes if the heart rate remains less than 60 beats per minute. When epinephrine is required, multiple doses are commonly needed.

Without a response to resuscitation and known or suspected blood loss, volume expansion with normal saline or blood at 10 mL per kg over five to 10 minutes may be needed. This may be repeated if there is an inadequate response. Uncross-matched type O Rh-negative blood is preferred when blood loss is substantial.

Postresuscitation Care

After prolonged resuscitation, monitoring in a neonatal intensive care unit or triage area is recommended. Hypoglycemia is common and associated with poor outcomes if glucose levels are not corrected. After prolonged resuscitation, newborns at 36 weeks' gestation or more should be evaluated for evidence of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. In term and late preterm infants with moderate to severe encephalopathy and intrapartum asphyxia, therapeutic hypothermia reduces major neurodevelopmental disability and mortality.

Discontinuing Resuscitation

The decision to discontinue neonatal resuscitation should be individualized based on gestational age, fetal conditions, resources, and the parents' wishes. The gestational age where viability starts is usually defined as between 22 and 24 weeks of age. If the fetal heart rate is not detectable at 20 minutes after birth despite resuscitation, the goals of care may need to be readdressed.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Editor's Note: This most recent update of the neonatal resuscitation guidelines involves minor changes to the overall algorithm (Figure 1). Much of the 2011 AFP article (https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/0415/p911.html) still applies. Yet, this update has some interesting elements. One is the reminder that nine out of 10 newborns will not require intervention and should be monitored on their mother's chest. In addition to pharyngeal and endotracheal suction, bulb suction of the nose and mouth should also be avoided because it causes more harm than good. When resuscitation is required, early positive pressure ventilation is most important and should be started within 60 seconds of birth. If following the algorithm to medications, it is important to note that multiple doses of epinephrine are commonly required in successful resuscitations, and the effectiveness of endotracheal epinephrine is limited by a five-minute delay.

Umbilical cord milking in preterm infants is still being debated because of the desire to expedite resuscitation. The guideline cautions against milking the cord in preterm infants before clamping to avoid intraventricular hemorrhage. A newer systematic review reports reduced intraventricular hemorrhage risk with umbilical cord milking or delayed cord clamping, but not both.1

One issue not addressed in the guidelines is a list of risk factors for complicated resuscitation that require increased birth attendance. The results are summarized in the accompanying table.2—Michael J. Arnold, MD, Contributing Editor

| Risk factor | Odds ratio for complicated resuscitation |

|---|---|

| Antepartum | |

| Fetal growth restriction | 20 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 16 |

| < 37 weeks' gestation | 2 |

| Intrapartum | |

| Fetal bradycardia | 25 |

| Chorioamnionitis | 18 |

| Forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery | 17 |

| Meconium-stained amniotic fluid | 17 |

| Placental abruption | 12 |

| General anesthesia | 11 |

| Emergency cesarean delivery | 2 |

References

1. Jasani B, Torgalkar R, Ye XY, et al. Association of umbilical cord management strategies with outcomes of preterm infants: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(4):e210102.

2. Berazategui JP, Aguilar A, Escobedo M, et al.; ANR study group. Risk factors for advanced resuscitation in term and near-term infants: a case-control study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102(1):F44–F50.

Guideline source: American Heart Association

Evidence rating system used? Yes

Systematic literature search described? Yes

Guideline developed by participants without relevant financial ties to industry? Yes

Recommendations based on patient-oriented outcomes? Yes

Published source: Pediatrics. January 2021;147(suppl 1):e2020038505E