Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(5):507-513

Patient information: See related handout on seizures in adults, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Seizures are transient signs and symptoms of abnormal, excessive, or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Up to 10% of adults have a seizure during their lifetime, with increasing incidence in people older than 55 years. One-third of people have a recurrent seizure within one year of an initial unprovoked seizure. Acute symptomatic (provoked) seizures recur less often, especially when provoking factors are addressed. After confirming a probable seizure, evaluation focuses on identifying provoking factors such as tumor, metabolic derangement, infectious disease, stroke, traumatic brain injury, medications, or substance misuse. Magnetic resonance imaging with an epilepsy protocol and electroencephalography should be performed as soon as practical. Lumbar puncture is useful if intracranial infection is suspected. Immediate initiation of anti-seizure medication reduces seizure recurrence by 35% within the first two years. Recurrence rates between three and five years are similar between patients who start anti-seizure medication immediately after the first seizure and those who do not. Restoration of driving privileges varies by state. After a seizure, safety concerns should be addressed, such as the need for a safety companion when bathing or swimming and the risks of ladders and other hazards.

The International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) defines seizures as a transient occurrence of signs or symptoms due to abnormal, excessive, or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain.1 The ILAE categorizes seizures by the location of onset in the brain: focal, generalized, or unknown; they are subcategorized by the presence or absence of motor symptoms and loss of awareness.1

In generalized onset seizures, abnormal electrical activity initiates throughout the brain. These types of seizures always include loss of awareness.1 Focal onset seizures begin in one area of the brain, although they may generalize to involve the entire brain and may or may not include loss of awareness.1 Motor symptoms can include the classic tonic-clonic movements as well as myoclonus or atonic seizures.1 Nonmotor symptoms of seizures may include emotional, sensory, and cognitive changes, or a lack of movement due to absence seizures.1

Most people with a first seizure do not have epilepsy. Epilepsy usually requires two unprovoked seizures occurring at least 24 hours apart, but the diagnosis can be made based on a single unprovoked seizure with at least a 60% risk of a second seizure in the next 10 years, or in the setting of an epilepsy syndrome.2 Determining the risk of a second seizure is an important part of the evaluation of the first seizure, although no formula exists to calculate risk and factors should be considered individually.

Epidemiology

The rate of first seizures is higher in low-income countries than in the United States.5 Low- and middle-income countries account for approximately 80% of epilepsy worldwide. This may be because of higher rates of risk factors for epilepsy, such as congenital conditions, intracranial infections, and traumatic brain injury.5 In high-income countries, first seizures are more common in people affected by social and economic deprivation.6 Worldwide, seizures are increased where there is inadequate access to health care.7

Types of Seizures

ACUTE SYMPTOMATIC (PROVOKED) SEIZURES

Acute symptomatic seizures, also known as provoked or situation-related seizures, are manifestations of an acute insult to the central nervous system. Stroke and central nervous system infection are the most identified provoking factors.8 Other provoking factors include metabolic derangements, such as electrolyte abnormalities, or toxic effects of medications, alcohol, or drugs, including overdoses.9 Provoking factors may be infectious, inflammatory, metabolic, structural, or toxic in nature10 (Table 111–15).

| Infectious Encephalitis Meningitis Neurocysticercosis Prion disease Toxoplasmosis Tuberculosis Inflammatory Celiac disease Hashimoto encephalitis Other autoimmune conditions Sarcoidosis Systemic lupus erythematosus Metabolic Hepatic failure Hypocalcemia (serum calcium < 8.5 mg per dL [2.13 mmol per L]) Hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 36 mg per dL [2 mmol per L]) or hyperglycemia (blood glucose > 450 mg per dL [24.98 mmol per L]) Hypomagnesemia (serum magnesium < 1.2 mg per dL [0.49 mmol per L]) Hyponatremia (serum sodium < 110 mEq per L [110 mmol per L]) Hypoxia Porphyria Renal failure Structural Arteriovenous malformations Cerebrovascular accident Intracranial lymphoma Neurosurgery Primary or secondary brain tumor Traumatic brain injury Toxic Alcohol withdrawal Prescribed medications (Table 2) Substance misuse (e.g., cocaine, phencyclidine [PCP]) Other Sleep deprivation |

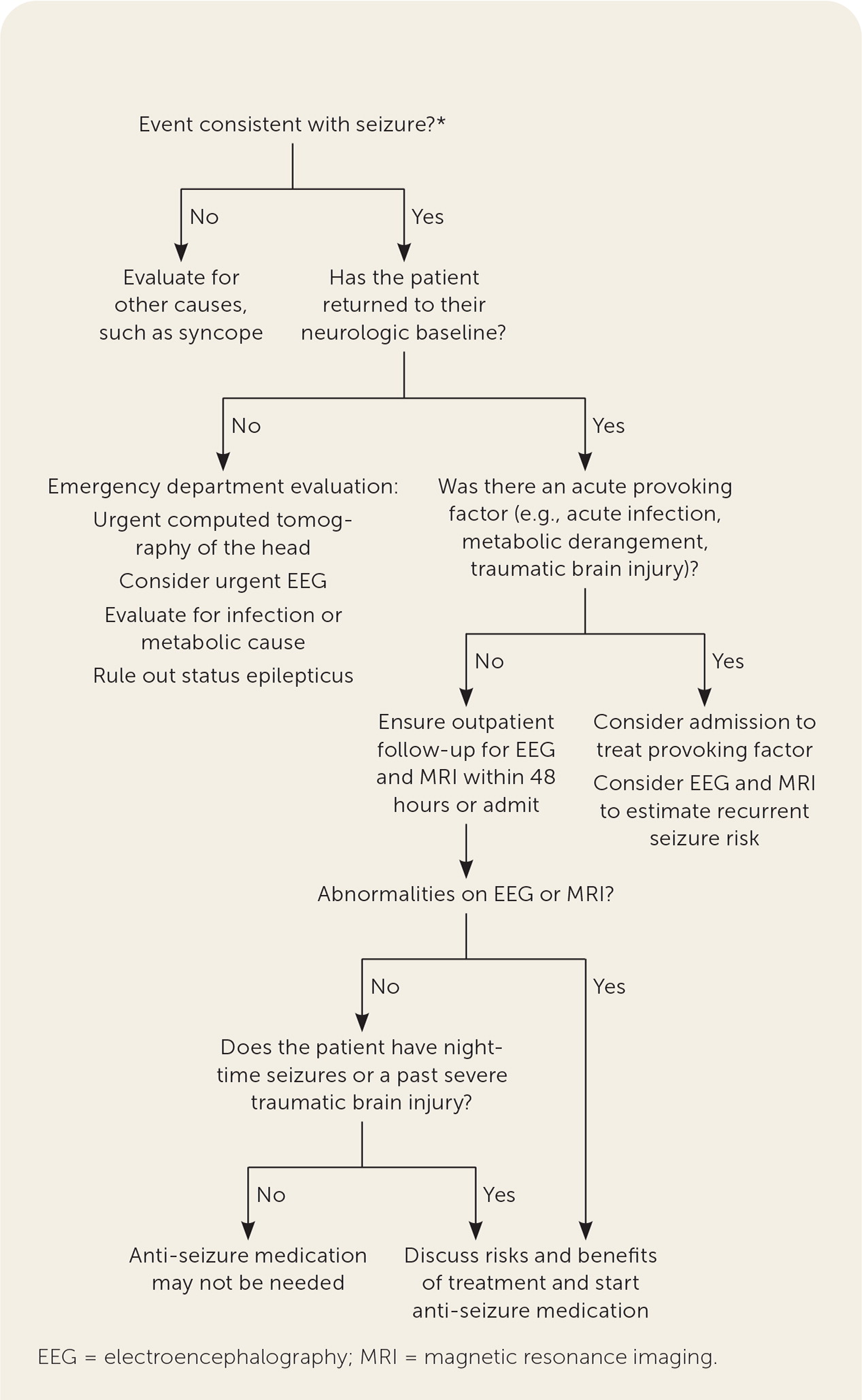

Approximately 40% of first seizures are associated with provoking factors. The evaluation after a first seizure should focus on identifying these factors10 (Figure 13,7,16–20). This allows for the treatment of an underlying condition, or an assessment of an increased risk of seizure recurrence, to reduce the risk of subsequent seizures.7

UNPROVOKED SEIZURES

Unprovoked seizures are divided into two categories: those with no known etiology, and those related to progressive, preexisting, or remote central nervous system injury. Unprovoked seizures with known etiologies include prior traumatic brain injury, congenital cerebral palsy, and remote central nervous system infection.21 Unlike in acute symptomatic seizures, the central nervous system insult does not occur within the same time frame as the seizure. Recurrence is more common in unprovoked seizures with known etiologies.22

PSYCHOGENIC NONEPILEPTIC SEIZURES

Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures (PNES) are seizure-like symptoms without abnormal electrical activity in the brain. They have psychological origins and have also been called pseudoseizures. The diagnostic standard for PNES is video-electroencephalography (EEG) monitoring during typical seizure-like activity.23

PNES does not rule out neurologic seizures, because PNES can coexist with neurologic seizures and epilepsy. In one study of more than 2,000 people with refractory epilepsy, 32% had PNES on video-EEG monitoring.24 In the same study, 5% of people diagnosed with PNES had epilepsy, and 2% were diagnosed with both.24

People with PNES commonly report negative health care experiences and are more likely than patients with epilepsy to have a mental health diagnosis, but both groups are similar in sex distribution and age at diagnosis.25,26 PNES treatment requires interdisciplinary care that includes effective mental health care and continuity of care. Cognitive behavior therapy may be more effective than usual care at reducing seizure-like activity in the short term.27 Patients may experience fear of not being taken seriously if they are perceived to have a psychiatric condition instead of a neurologic one, which can interfere with treatment effectiveness.26

Evaluation

The clinical evaluation is focused on determining whether the patient had a seizure or experienced a seizure mimic, which includes syncope, migraine, or stroke without seizure.9 If a seizure is suspected, the evaluation focuses on identifying provoking factors. The evaluation does not vary based on seizure classification.

HISTORY

In addition to the patient's recollection of events, witness statements are essential. Seizure is more likely if tongue biting, head turning or twisting, limb jerking, or urinary incontinence occurred. Prodromal symptoms, such as déjà vu, mood changes, hallucinations, confusion, or post-event amnesia, also increase the likelihood of seizure. Factors that suggest diagnoses other than seizure include chest pain, nausea, dyspnea, palpitations, and presyncopal symptoms such as lightheadedness, tunnel vision, and dizziness.7,16

MEDICATION AND SUBSTANCE USE

Many medications can contribute to having a seizure; therefore, evaluation should include a comprehensive history of medication and substance use, including those recently started or stopped.28 Common medications associated with an increased risk of seizure include bupropion (Wellbutrin), diphenhydramine (Benadryl), and tramadol.29 Table 2 lists other medications associated with an increased risk of seizure.17,18,28,30–33 Seizures can be caused by use of or withdrawal from substances including alcohol, opioids, stimulants, and cocaine.17

| Analgesics Fentanyl Meperidine (Demerol) Morphine (epidural or intrathecally) Tramadol Antihistamines First-generation more likely than second-generation Anti-infectives Carbapenems Cephalosporins Isoniazid Decongestants Pseudoephedrine Immunosuppressants Cyclosporine (Sandimmune) Methotrexate (intravenously or intrathecally) Tacrolimus (Prograf [orally or intravenously]) Psychiatric Antidepressants Bupropion (Wellbutrin) Trazodone Tricyclic antidepressants Venlafaxine Antipsychotics Chlorpromazine Clomipramine (Anafranil) Clozapine (Clozaril) Stimulants Atomoxetine (Strattera) Miscellaneous Baclofen (Lioresal) Lindane Theophylline Zolpidem (Ambien) |

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

A complete neurologic examination should be conducted after the postictal period when the patient is alert and no longer disoriented to identify a neurologic provoking factor, such as lateralizing cortical deficits (i.e., unilateral weakness or aphasia).34 Other provoking factors include signs of infection, cerebrovascular disease, or metabolic derangement.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Although the value of laboratory analyses is uncertain, some can identify provoking factors. A complete blood count can suggest central nervous system infection. A comprehensive metabolic panel may indicate hyperglycemia, electrolyte disturbances, particularly hyponatremia, or renal or hepatic disease. Although a toxicology screen could indicate the presence of provoking drugs, evidence is insufficient to suggest screening all patients with a first seizure.18

No laboratory study can accurately diagnose a recent seizure, but a normal serum prolactin level may help rule out seizure in a patient with suspected PNES.35 However, one study of patients undergoing continuous EEG monitoring questioned its usefulness, because 25% of patients with nonepileptic seizures had an elevated prolactin level and 15% of patients with neurologic seizures did not.36 Although serum prolactin level may be elevated after a seizure, other events cause similar elevations. In one study, prolactin was elevated in 60% of patients after vasovagal syncope and 78% of patients after seizure.37

NEUROIMAGING

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using an epilepsy-specific protocol is indicated for patients with a first nonfebrile seizure who do not have any evidence of provoking factors on initial workup, and it should be considered for all patients.9,18 An epilepsy-specific MRI protocol includes thin slices to improve sensitivity for lesions associated with epilepsy. Even if initial regular MRI imaging was performed, an epilepsy-specific MRI is recommended.3,9,19 If MRI is not available, computed tomography may be considered.

LUMBAR PUNCTURE

With fever, stiff neck, immunocompromise, or altered mental status, a lumbar puncture after normal initial imaging can demonstrate intracranial infection. In patients who are awake and alert and without signs, symptoms, or risk factors for infection, there is insufficient evidence for lumbar puncture.18

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY

EEG should be performed as soon as possible, ideally within 24 hours after an unprovoked seizure when the test is most likely to capture epileptiform activity.3,7,9,18 When initial EEG results are normal, a follow-up study, such as sleep-deprived EEG or prolonged ambulatory EEG, can capture epileptiform activity. It is recommended that these follow-up studies be completed as soon as possible, ideally within seven days.39 The presence of EEG abnormalities nearly doubles seizure recurrence risk, which impacts the decision to treat.18,21

EEG should be done only in patients whose clinical presentation is consistent with a possible seizure, such as witnessed tonic-clonic movements, a postictal period, and evidence of tongue biting or other indicative physical examination finding. In approximately one-half of patients with a first seizure, an EEG abnormality is identified. EEG abnormalities are also found in 4% of patients without seizure.7 EEG cannot rule out seizure in a patient who had unwitnessed loss of consciousness. Normal EEG results do not eliminate epilepsy because up to 10% of patients with epilepsy initially have a normal EEG.7

Outpatient Evaluation

Patients who are clinically stable and lack a clear provoking factor can be safely discharged from the emergency department.20 Admission for EEG and neuroimaging is warranted if outpatient studies cannot be completed in a timely manner.

Prevention of Recurrent Seizures

About one-third of adults experience a second seizure within one year of an unprovoked seizure, and nearly one-half experience a second seizure within two years.21 The risk factors of nighttime seizure, EEG abnormalities, abnormal brain imaging, and history of brain insult more than double the risk of recurrent seizure.21

The decision to start anti-seizure medication is based on assessment of the patient's risk of recurrent seizure. The patient's estimated risk of recurrence based on factors or findings on workup can be provided with the medication risks and benefits for shared decision-making. Declining medication is reasonable, especially without risk factors.

Medications reduce the absolute risk of seizure recurrence by 35% within the first two years of treatment with immediate initiation of anti-seizure medications after the first seizure.21 The benefit of anti-seizure medication wanes over time. Patients who do not start treatment with anti-seizure medication have equivalent seizure rates between three and five years as patients who started anti-seizure medication after the first seizure.21,40 Despite early seizure reduction, quality of life is not improved with medication.21 Anti-seizure medications do not affect mortality after a first or subsequent seizure.40,41 Up to 31% of patients report adverse effects from anti-seizure medications. 21 Most adverse effects are mild and reversible but include cognitive changes, coordination difficulty, somnolence, and personality changes.21,42

Patients may choose medication to shorten driving restrictions, because driving privileges often require a seizure-free period. Patients taking anti-seizure medication are more likely to be driving after two years.43 Anti-seizure medication selection is discussed in a previous article on epilepsy treatment (https://www.aafp.org/afp/2017/0715/p87.html).

Safety Counseling

Each state has its own laws regarding driving restrictions and physician reporting. Some states restrict driving for 12 months after being seizure free, whereas others allow driving to be resumed at the discretion of the treating clinician. The Epilepsy Foundation summarizes requirements for each state at https://www.epilepsy.com/driving-laws.

Patients with a first seizure should be counseled on avoiding hazardous situations in case of a subsequent seizure. Physical hazards such as ladders and sharp objects should be avoided, and a safety companion is recommended when swimming or bathing.7

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Adams and Knowles44 and Wilden and Cohen-Gadol.45

Data Sources: We searched PubMed for clinical trials and reviews using keywords “seizure” “first seizure” and “seizure NOT febrile NOT epilepsy.” We searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Essential Evidence Plus including InfoPOEMs, and UpToDate. Also searched were the American Academy of Neurology, American College of Emergency Physicians, and the International League Against Epilepsy sites for clinical practice guidelines, as well as the Epilepsy Foundation site. Search dates: February 9, 2021; April 12, 2021; April 14, 2021; January 12, 2022.

The authors thank Angelica Lee, MD, FAAN, for her suggestions and assistance with the algorithm.