Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(3):292-296

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Case Scenario

An eight-year-old boy presents to your office for his annual well-child examination. His grandmother is his legal guardian and is concerned because he has difficulty finishing his homework and gets distracted easily by noises at home. His second-grade teacher informed the grandmother that the patient performs significantly below grade-level expectations. His medical history is notable for prematurity (28 weeks of gestation) and grade 2 intraventricular hemorrhages. His grandmother asks you to prescribe a chewable long-acting stimulant such as the one his cousin takes to improve his school performance. You provide Vanderbilt assessment forms (https://www.nichq.org/sites/default/files/resource-file/NICHQ-Vanderbilt-Assessment-Scales.pdf) for the patient’s grandmother and teachers to complete.

Clinical Commentary

EPIDEMIOLOGY

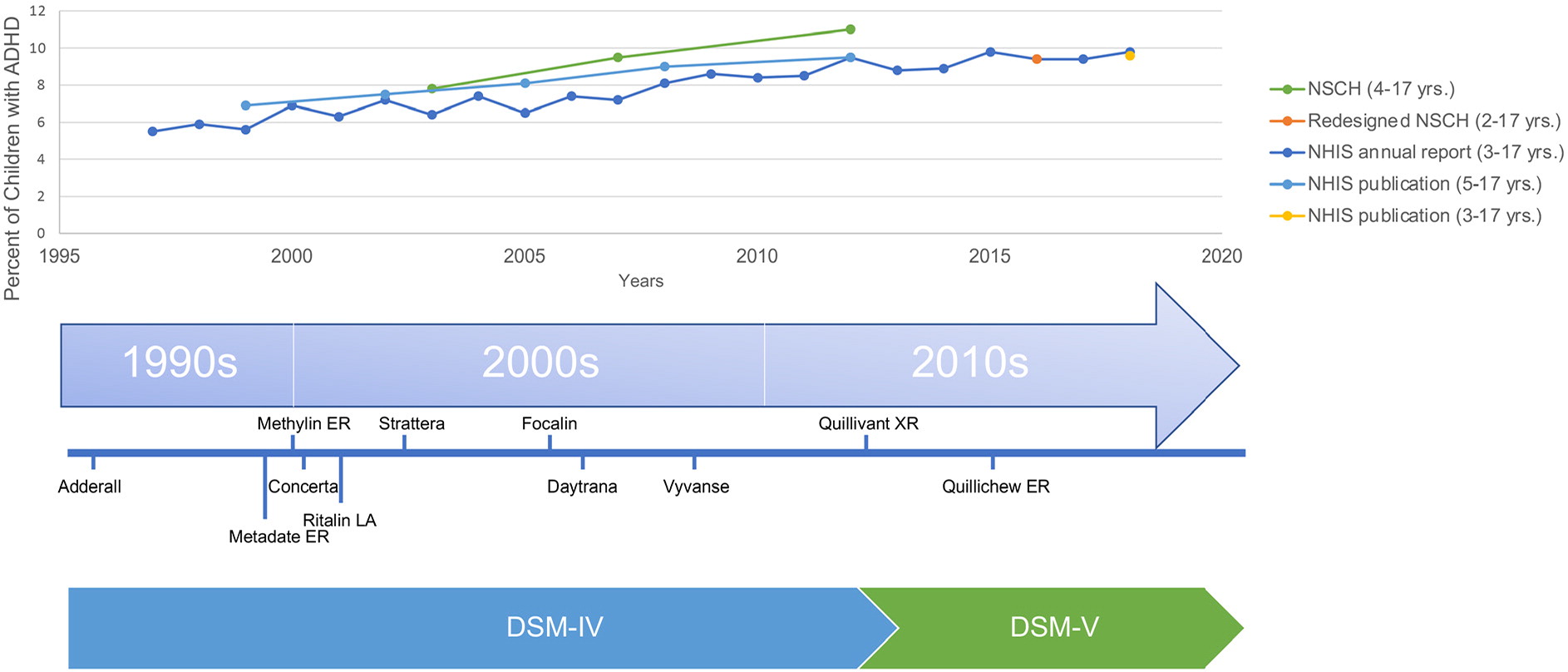

Rates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) have increased over the past several decades (Figure 1).1 A nationwide, population-based, cross-sectional survey found that ADHD rates increased by 67%, from 6.1% in 1997 to 1998 (when the survey first included questions on ADHD) to 10.2% in 2015 to 2016.2 Similar increases have been observed in other Westernized countries.3,4 During this period, there was a concordant increase in the use of stimulants.1,5 In contrast to the increase in ADHD diagnoses, the frequency and severity of ADHD symptoms have stayed relatively constant.3,6 It is unknown if the increase in ADHD diagnoses and the use of stimulants represent changing neurobiology, improved detection, expanding definitions of disease, the impact of pharmaceutical marketing,7 or other factors.

DEFINITIONS OF DISEASE

There is evidence that ADHD is “dimensional,” meaning that hyperactivity, inattentiveness, and impulsiveness exist on a continuum with normal behavior.8 The cutoffs that define abnormal are subject to interpretation and change. Each subsequent version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) has expanded the definition of ADHD.9 In 2013, the DSM-5 lowered the percentage of criteria needed for diagnosing ADHD in older adolescents and increased the age by which behaviors must have first appeared (from seven to 12 years).10 Proponents of the new criteria contend that these changes were made out of concern for the previous underdiagnosis of ADHD; however, critics point to the high proportion (78%) of the DSM-5 ADHD Working Group members with financial conflicts of interest that may have influenced the expansion.11

The significant variation in stimulant prescriptions across states suggests that factors beyond underlying neurobiology may dictate diagnosis and treatment. In Hawaii, 1 in 100 children is prescribed stimulants, whereas the rate is nearly 1 in 7 in Alabama.12 Geographic variations may be due to differences in clinician characteristics, such as knowledge, training, or attitudes, or differences in parental expectations or interpretations of child behavior. Clinician subjectivity may also play a role. In a case vignette study, clinicians were twice as likely to diagnose ADHD in a child described as male compared with a child described as female with the same behavior.13

CHILDREN YOUNG FOR THEIR GRADE

There are significantly higher rates of ADHD in children who are young for their school grade.14,15 One study found that ADHD is more than twice as likely to be diagnosed in the youngest month compared with the oldest month of age eligibility.14 These findings suggest that comparisons across children in the same grade play a role in the diagnosis of ADHD and that relative immaturity can be misdiagnosed as ADHD.

RACIAL DISPARITIES

Although older studies found that ADHD is more common in self-identified White children,16,17 more recent studies have shown that Black children are equally if not more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD.18,19 It is unclear what is leading to these temporal trends. Biases and variable interpretations of behavior may play a role because questionnaires used to diagnose ADHD rely on parental and teacher reports of a child’s behavior.20–22

COMORBIDITIES AND MISDIAGNOSES

Approximately one-third of children with ADHD have a comorbid learning disorder.23 Rates of psychiatric comorbidities are substantial. One study found that 27% of children with ADHD have a conduct disorder, 18% have anxiety, and 14% have depression.24 Children with ADHD have higher rates of adverse childhood experiences compared with children without ADHD.25 In addition to psychiatric conditions, children with obstructive sleep apnea are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD.26 Many symptoms of ADHD overlap with other psychiatric and nonpsychiatric conditions; therefore, it can be challenging to distinguish between them.27

BENEFITS OF DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Having a diagnosis of ADHD may allow the child to feel empowered or more confident in school settings, invoke more understanding from caregivers and teachers, allow the child to externalize some of their behaviors, and prevent them from thinking of themselves as “bad.”28,29 A diagnosis of ADHD allows the student to qualify for an individualized education plan that can help provide specialized instruction.

There are clear benefits of stimulant use in specific populations. In children with moderate to severe ADHD, stimulants have been shown to reduce core ADHD symptoms and improve quality of life.30 Stimulants can improve math and reading performance.31–33 There are also benefits to social behavior outside of school, including crime reduction.34 Fewer studies have examined the benefit and harm profiles of stimulants in children with mild symptoms, and studies that have been conducted did not find that benefits outweigh harms.35,36

HARMS OF DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Although stimulant medications are generally considered safe, there can be significant adverse effects, including insomnia, appetite suppression, headaches, and tics.39,40 Insomnia can be particularly troublesome because insufficient sleep can worsen the patient’s behavior.41 There are statistically significant increases in heart rate and blood pressure with stimulant use, although these increases may not be clinically significant.42 It is unclear whether long-term stimulant use is associated with decreased height.43,44 At the societal level, stimulant medications can be diverted to individuals without a prescription, can be used in attempted overdoses, and can increase calls to poison control centers.45,46

When children with underlying anxiety or depression are misdiagnosed with ADHD, they may not receive other important treatments such as counseling or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. When children with adverse childhood experiences are mislabeled as having ADHD, they may miss opportunities to alter their toxic environment or access resiliency resources. Children with learning disorders unrelated to ADHD may lack important educational support.

| The prevalence and pharmacologic treatment of ADHD have increased over the past several decades. |

| It is unknown if the trends in ADHD diagnosis and treatment represent changing neurobiology at a population level, improved detection, expanding definitions of the disease, the impact of pharmaceutical marketing, or other factors. |

| ADHD is more likely to be diagnosed in children who are in the first month of school-age eligibility compared with the 12th month of eligibility, suggesting that some ADHD diagnoses may represent relative immaturity and overdiagnosis in children who are young for their grade. |

| The balance of benefits and harms of stimulant use in children with mild symptoms is unclear. |

Patient Perspective

Many parents and guardians struggle with young children who exhibit challenging behavior and psychosocial limitations. These caregivers sometimes find comfort when a specific condition such as ADHD is diagnosed. One of us has firsthand knowledge of a young child with episodes of anxiety and unexplained bouts of “depression.” Her parents avoided seeking diagnoses beyond dyslexia, which led to tutoring and improved learning, reducing her anxiety and improving her mood. Other parents in this situation may have sought the comfort of an ADHD diagnosis. This patient’s story leads us to ask if there are nonmedical ways to help children with symptoms that may lead to a diagnosis of ADHD.

Humans have an extended childhood for a reason: so we can learn to be adults. Children have many quirks, most of which they outgrow or learn to control in socially acceptable ways. As parents and grandparents—and yes, even once as children—it has been our observation that many of the ills of childhood can be alleviated by exercise in the form of unstructured play and organized sports. The benefits of exercise are also supported by research.49 Outdoor play and games have physiologic benefits and provide important lessons in productively working with others. Other changes that can have a positive effect are emotion-regulating video games or adding a pet to the family.50,51 Medicating children to change their behavior may help them sit quietly at school, but viewing medication as a first-line solution may mask problems with the school or home environment and inhibit the development of important life skills.

ADHD medications can have both positive and negative effects on behavior. Common adverse effects such as appetite loss and insomnia can be unhealthy for growing children. We also wonder how many parents would view less common adverse effects such as possible growth restriction as reasonable risks if they were routinely advised of them.52,53 We understand that the family’s living circumstances may preclude the application of some nonmedical remedies, but this is an opportunity for the physician and the family to engage in shared decision-making to help a child with ADHD-like symptoms.

Resolution of Case

The patient and his grandmother return one month later with the completed Vanderbilt forms. The forms suggest that he may have predominantly inattentive ADHD, although he also screens high in the anxiety and depression areas. You ask the grandmother what he might be anxious or depressed about, and she mentions the death of his mother two years ago. You suggest grief counseling and provide a list of mental health clinicians that accept his insurance. His prematurity and consistently low academic evaluations make you suspect an unrelated underlying learning disorder, and you recommend that the school evaluate him for an individualized education plan. You discuss the potential adverse effects of stimulants, including insomnia and appetite suppression, and the uncertain benefit of these medications given his other underlying diagnoses. The grandmother decides to defer pharmacologic treatment for now. You refer the patient for behavior therapy, review the tenets of good sleep hygiene, and suggest they follow up with you in six months.

The authors thank Andi Jaffe for her help with the literature review and creation of the figure.