Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(6):624-625

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Clinical Question

In the primary care setting, what is the best approach for the initial evaluation of patients with suspected dementia?

Evidence Summary

When there is concern for cognitive impairment, based on history or expressed by family members, quick and effective tools for the initial evaluation of dementia are essential for diagnosis. Many tools are available, including the General Practitioner assessment of Cognition (GPCOG) and the Mini-Cog instrument. If the initial evaluation is positive, an in-depth cognitive evaluation should be performed.

The GPCOG, available at https://gpcog.com.au, takes less than four minutes to complete. It is a six-item verbal evaluation that incorporates tests of memory, orientation, and clock drawing followed by a brief questionnaire for a family member or close friend to answer. It has been evaluated in a single large, well-designed primary care study in Australia and had similar accuracy to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).1 Compared with the reference standard of a comprehensive interview, it was 79% sensitive and 92% specific (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] = 9.9; negative likelihood ratio [LR–] = 0.23).

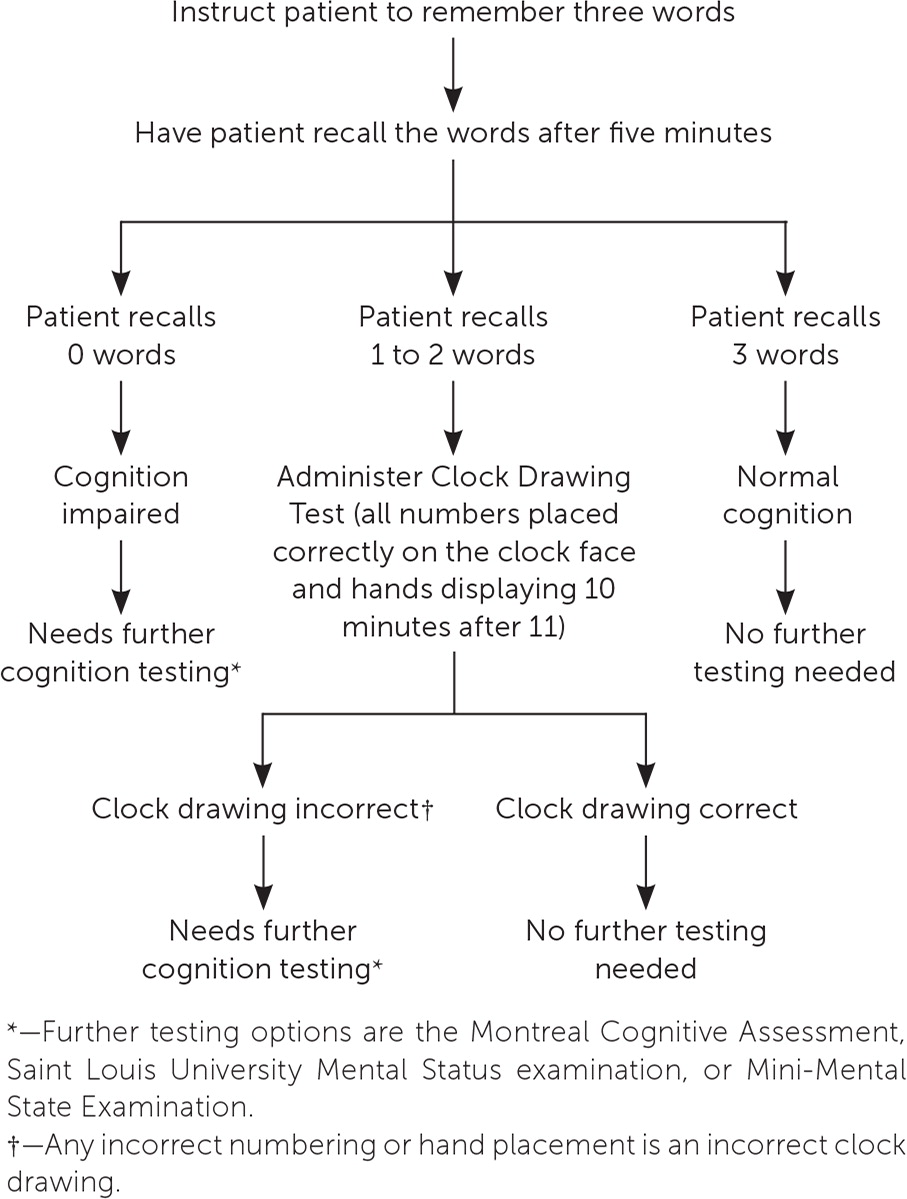

The Mini-Cog is a three-minute test performed in the office setting (Figure 12,3). A Cochrane review identified four studies that reported the accuracy of the Mini-Cog in primary care, with a sensitivity of 76% to 100% and specificity of 27% to 85%.4 The study with the least risk of bias showed a sensitivity of 76% and specificity of 73% (LR+ = 2.8; LR− = 0.33).4

If the patient has a positive result on the Mini-Cog or a similar initial screening test, the patient should return for further dementia evaluation. The most widely used cognitive examinations are the MMSE, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) examination. These screenings can be used for initial testing if time allows. The tests use a 30-point scale; however, the SLUMS examination and MoCA also test for verbal fluency and abstraction.5 The cutoff points indicating dementia vary between tests, and there is variability of agreed cutoffs for each screening. Although the MMSE is a widely accepted research tool and commonly recommended, it is copyright protected and should not be used without paying royalties.6–8

The MoCA takes approximately 10 minutes to complete and includes eight cognitive domain tests.9 Information about how to administer and interpret the MoCA is available at https://mocacognition.com. A Cochrane review concluded that a score below 26 indicated cognitive impairment, with a sensitivity of at least 94% and a specificity of 60% or lower (LR+ = 2.35; LR− = 0.1).9

The SLUMS examination takes seven minutes for 11 items. Information about how to administer and interpret the SLUMS examination can be found at https://www.slu.edu/medicine/internal-medicine/geriatric-medicine/aging-successfully/pdfs/slums_form.pdf. In a systematic review, the SLUMS examination, with a cutoff score of 19 or below, had a sensitivity of 93% and a specificity of 96% (LR+ = 23; LR− = 0.07) for detecting dementia; for mild cognitive impairment, the cutoff score was 26 or below and had a sensitivity of 64% and specificity of 65% (LR+ = 1.8; LR− = 0.55).10

Applying the Evidence

A 75-year-old woman comes to your clinic with her husband. Her husband is concerned that her memory seems to be worsening. You perform the Mini-Cog, and she has a score of 1 on the word recall test and correct number placement on the clock face but incorrect hand placement. This indicates a positive screen, and the patient is asked to return for further evaluation. When the patient returns, she is evaluated using the SLUMS examination and has a score of 19, indicating dementia.