FUNDED CONTENT BY WILEY

This educational activity is supported by an independent medical educational grant from Exact Sciences.

This grant-funded resource is made available by the AAFP to provide convenient access to information that may be of interest. It should not be considered an AAFP endorsement or recommendation of the grantor’s products, services, policies, or procedures. Journal editors were not involved in the development of this content.

CME Bulletin - August 2025

Colorectal Cancer: Screening and Diagnosis

Jason Domagalski, MD, FAAFP; Medical Director, Physician Assistant Residency, Primary Care Clinic, Clement J. Zablocki VA Hospital, Milwaukee, WI

Erratum: In the original publication of this article, several references were inadvertently omitted from the reference list. As a result, the numbering of references from number 6 onwards was altered, potentially causing confusion. Additionally, copyediting errors were identified and corrected. We apologize for these errors. The corrected reference list has been updated accordingly.

CME Quiz available at https://health.learning.wiley.com/courses/cme-bulletin-crc/

1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ and AAFP Prescribing Credit. For information on applicability and acceptance of continuing medical education credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board.

Medical writing support was provided by Dr R.G.; Reviewed by Dr C Kruszynski and Dr S Kundu, John Wiley and Sons.

Learning Objectives:

• Understand the epidemiology and risk factors of colorectal cancer (CRC)

• List the recommended screening methods for CRC and their advantages and limitations

• Describe the clinical guidelines for CRC screening in the United States

• Develop patient-centered communication skills to effectively encourage patients to participate in CRC screening programs

• Implement strategies to bridge the care gap between preventative care and CRC screening within the healthcare practice

Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most diagnosed cancer in the United States, and the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths1. Globally, there were 1.9 million new CRC cases diagnosed in 2020, with 930,000 estimated deaths, whereas in the U.S., an estimated 150,000 new cases were diagnosed in 2023, with approximately 50,000 deaths1. Additionally, the number of CRC cases is increasing at the rate of 1-2% per year in individuals under 55 years old, with the Native American/Alaskan population and Black population experiencing the greatest rates of mortality1. CRC subtypes can be defined based on the location of the cancer in the large intestine (proximal colon, distal, or rectal) or based on the mechanism of occurrence (sporadic, hereditary, or colitis-associated). A number of environmental, lifestyle, and genetic factors may play a role in the carcinogenesis of CRC. For instance, physical inactivity is associated with elevated risk of CRC, whereas high levels of physical activity are associated with increased survival rate in CRC patients. Alcohol consumption, obesity, cigarette smoking, and consumption of red meat are associated with an increased risk of developing CRC. On the other hand, consumption of high fiber vegetables is associated with lower risk of developing CRC2.

CRC screening for individuals at average risk of CRC are discussed here. Whereas recommendations for individuals with a family history of CRC, polyposis syndromes, or underlying inflammatory bowel disease are not discussed here. Most colorectal cancers develop from slow-growing benign colorectal polyps. This pathway from polyp to early cancer to late cancer provides an opportunity to intervene in disease development at the polyp or early cancer stage using screening tests.

CRC Screening: Challenges and Opportunities

Surveys of healthcare providers (HCP), clinicians, and primary care workers3 have revealed that HCPs face two significant challenges with respect to CRC in the clinical setting. Firstly, a low screening rate is a significant barrier to improving mortality and survival in CRC3. It is important to note that the 5-year survival for CRC is ~90% when diagnosed at an early stage, and therefore, increasing screening rates is critical to improving mortality and survival rates1. Therefore, it is necessary to educate HCPs and primary care workers on the importance of screening, so that they may provide accurate and relevant information to patients. Secondly, a care gap exists between preventative care and CRC screening. This is often due to a lack of information amongst patients regarding the importance of screening, as well as the different types of tests available4. In this situation, this care gap can be addressed by providing communication strategies and medical education to care providers.

Unlike many other developed countries, the US does not have a national screening program where individuals are systematically invited/reminded to be screened at certain time points in their lives. Instead screening is opportunistic and ad hoc. Unlike other countries with national screening programs, individuals at average risk of CRC in the US are offered a choice of different screening tests, with different degrees of accuracy/efficacy (discussed below). Clinician biases/education, patient understanding, expenses, and insurance coverage can all influence such choices.

Analysis of CRC incidence globally reveals that it appears to be higher in countries with a high human development index, and increases as a country adopts a more Western lifestyle. Thus, CRC remains an economic and social burden primarily in developed countries1. Nevertheless, unlike other types of cancers, CRC remains a highly preventable disease, if screening strategies can be implemented effectively. In the US, screening is primarily implemented on an ad hoc and opportunistic basis, whereas in European countries, a more systemic and organized approach has been implemented4.

CRC Screening Guidelines for Average Risk Individuals

Globally, in countries where CRC screening is systematically conducted on a national basis, screening is recommended to be initiated at the age of 505. However, in 2021, the United States Preventive Services Taskforce (USPSTF) recommended lowering the age of starting CRC screening to 45 for individuals at average risk of CRC6,7. Additionally, for African Americans, who are at higher risk of developing CRC, screening is now recommended to start at the age of 40 by the American College of Physicians8. These guidelines are broadly similar to the guidelines proposed by the American Cancer Society (ACS), which recommend starting screening at age 45 for individuals at average risk of developing CRC8,9. On the other hand the CRC screening guidelines proposed by the American College of Gastroenterologists (ACG) and published by the American Association of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommend regular CRC screening for average-risk individuals aged 50-75 years, and only urge physicians to consider screening for individuals aged 456.

Screening Tests Used in the Clinic

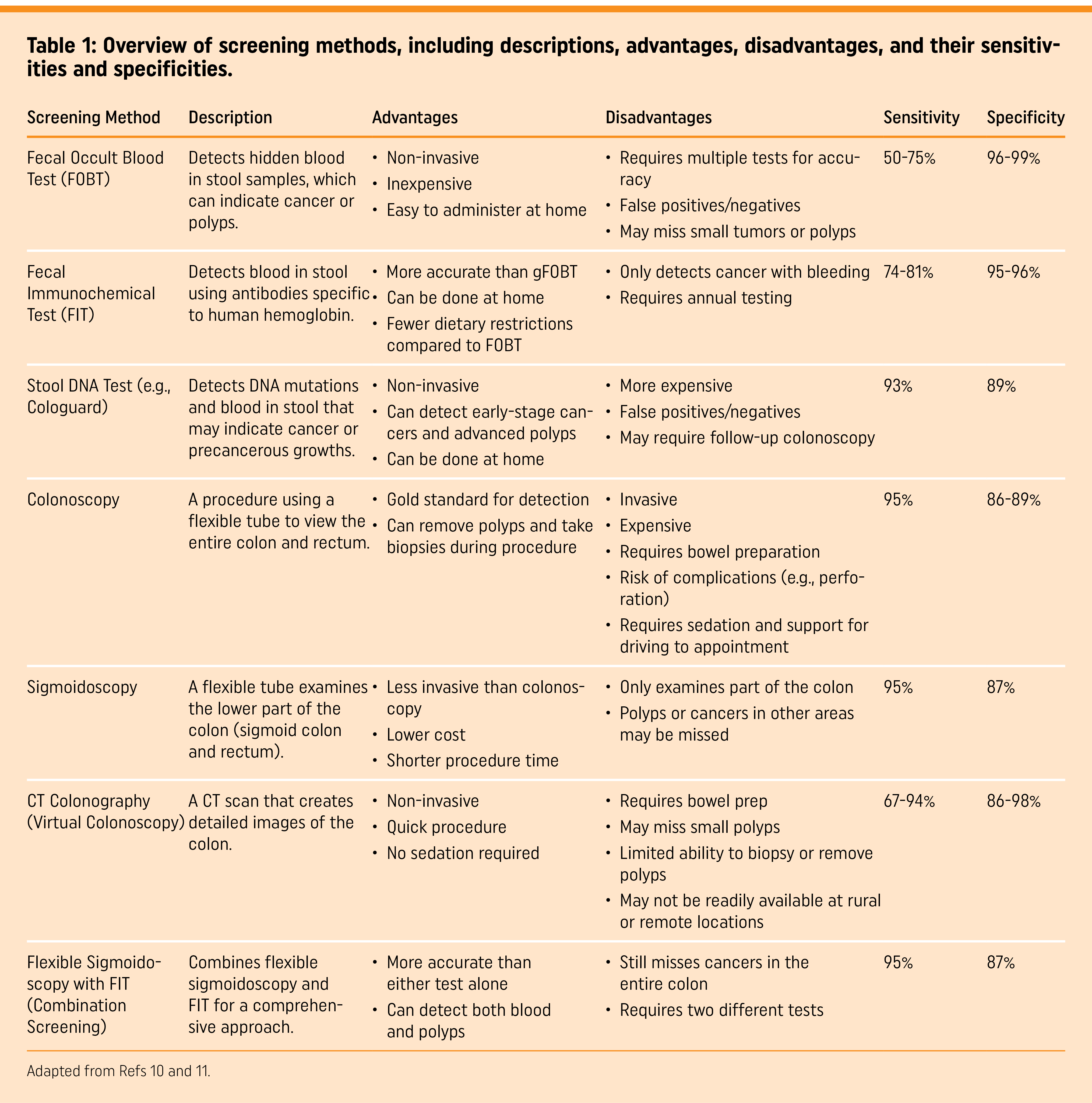

Several different types of screening tests are currently available for CRC (Table 1). These include stool-based tests, tests that involve direct visualization (colonoscopy), as well as emerging screening strategies that make use of molecular markers.

Stool-based tests

Stool-based tests rely on the detection of the presence of occult blood in the stool sample of the individual. The main principle behind stool-based tests is that CRC causes occult bleeding, which may be detected in the stool10. There are three main types of stool-based tests9: Guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests (gFOBT), fecal immu-nochemical tests (FIT), and fecal immunochemical test-DNA or multi-target stool DNA that includes FIT (FIT-DNA (mt-sDNA)).

gFOBT detects pseudo peroxidase activity in the stool and is an indirect measure of hemoglobin in the stool10. Several controlled trials have demonstrated that screening with gFOBTs every 2 years results in a reduction of CRC mortality by 9-22%9. Specifically, several studies have also compared the efficacy of annual vs biennial gFOBT testing, and demonstrated a modest benefit for annual rather than biennial testing. gFOBT remains the most cost efficient of all CRC screening strategies as of 202511.

The FIT is an antibody-test that directly measures the level of hemoglobin in the stool. Unlike the gFOBT, the FIT has greater sensitivity, is not affected by diet, and requires only one stool sample, thus resulting in greater adherence among patients for screening10. Consequently, annual FIT has almost replaced the gFOBT as the stool test of choice when it comes to CRC screening10. Observational studies have demonstrated a 10% reduction in CRC incidence and a 62% reduction in CRC-associated mortality attribut-able to FIT12.

Compared to gFOBT and FIT, which rely on the detection of hemoglobin in stool samples, the FIT-DNA or mt-sDNA test relies on the detection of abnormally methylated DNA regions within CRC cells that are shed in the stool10. The challenge in this test is in identifying the CRC DNA from the bacterial DNA, which are most abundant in blood. Similar to the FIT, there are no dietary modi-fications required; the mt-sDNA test has a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 85%12. This test is recommended to be performed every 1-3 years rather than the annual or biennial screening recommended for FIT or gFOBT. The mt-sDNA has a number of advantages such as higher sensitivity and less frequent screening, but also suffers from the disadvantages of higher cost and higher false-positive rate compared to FIT10,12.

Overall stool-based tests have a number of advantages compared to invasive tests that require direct visualization, such as non-invasiveness, the ability to perform tests at home, and low cost10.

Positive results on stool tests will need to be followed up with visualization investigations (below).

Direct visualization

There are four primary types of tests that involve direct visualization of the colon. These include: flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, computed tomography colonography (CTC), and capsule colonoscopy.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy enables direct visualization of the distal portion of the colon and the opportunity to biopsy as well as remove polyps. Prior preparation to successful testing involves the administration of enemas with or without oral magnesium citrate, and no sedation is required. Analysis of a number of long-term randomized controlled trials that compared the effects of flexible sigmoidoscopy compared to no screening demonstrated a significant decrease in CRC incidence as well as CRC-associated mortality10. Flexible sigmoidoscopy is recommended every 5 years by the USPSTF7,9.

Colonoscopy is perhaps the most effective single application method for CRC screening and is indicated after one or more non-in-vasive tests are positive10. Colonoscopy involves the use of a long flexible tube called a colonoscope that is fitted with a light and a camera, which enables the visualization of the entire colon as well as excision of any polyps that may be found. Colonoscopy requires individuals to undergo sedation, dietary modification, and purgative preparation, as well as the assistance of someone to transport them after the procedure11. Lastly, colonoscopy is associated with a small risk of colonic perforation or bleeding.

CTC allows scan visualization of the entire colorectum. CTC is typically performed after administration of a bowel preparation and is an agent to radiographically tag stool for digital subtraction11. Compared to colonoscopy, CTC has a per-person sensitivity for adenomas that ranged from 66.7-93.7% with specificity values ranging from 96-97.9%11. CTC may be administered in a variety of settings ranging from urban hospital centers to tertiary community centers. Barriers to greater uptake of CTC may include lack of insurance reimbursement and the need for bowel cleansing, which is a major factor affecting patient adherence13,14.

Lastly, capsule colonoscopy involves the ingestion of a pill-sized camera that records images as it travels through the upper GI tract to reach the colon. This test is minimally invasive and requires no sedation but does require effective bowel preparation. Capsule colonoscopy is not currently recommended by the FDA or the USPSTF as a first-line screening test. Capsule colonoscopy is only recommended for patients whose colonoscopy results were indeterminate. Capsule colonoscopy results do need to be confirmed by a standard colonoscopy11.

Emerging screening strategies

With the advent of genomic sequencing technology and the enhanced cost-effectiveness of sequencing in recent years, non-invasive screening strategies such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)-based tests and blood based tests are currently being developed. ctDNA-based tests or liquid-biopsy-based tests rely on the detection of DNA sequences from apoptotic tumor cells that are found in blood circulation11. Sequencing of these DNA fragments can reveal mutations present in tumor cell DNA and reveal tumor-specific markers and also elucidate the tumor burden11. Similar to the detection of ctDNA in the circulation, CRC cells can also be detected in the circulation, which can be isolated from blood samples by using physicochemical or cell sorting techniques based on cell surface molecules11. ctDNA analysis can be used for prognosis or surveillance for recurrence in patients already diagnosed with CRC.

Several blood-based screening methodologies are currently being tested in clinical trials for CRC screening. In August 2024, the FDA granted approval to SHIELD, the first blood-based screening method approved for the primary screening of CRC15. One of the challenges of implementing a non-invasive blood-based screening methodology is that it must meet the stringent Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) guidelines to be covered by Medicare/Medicaid16,17. These include a sensitivity greater than or equal to 74% and a specificity of 90% or greater for CRC16. A recent report presented at the ESMO 2024 conference on a new blood-based screening method provided promising preliminary results, with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 90.1% for CRC15. These results, therefore, highlight the great potential of this new screening methodology in both meeting the CMS guidelines and as a potential alternative to the current stool-based and colonoscopy-based screening guidelines.

Lastly, apart from ctDNA markers, epigenetic markers involving an alteration in the methylation status of certain genes can be used for screening to predict disease progression or to predict response to treatment. Methylome analyses have revealed that the CRC cell can accumulate several hundred abnormal methylation marks, which may alter the expression of tumorigenic genes11. Recently, an assay to detect methylation at the septin9 gene was approved by the FDA for CRC screening. This assay can reliably identify CRC patients with a 70% sensitivity and a 10-20% false-positivity rate; therefore, this assay may have limited utility18.

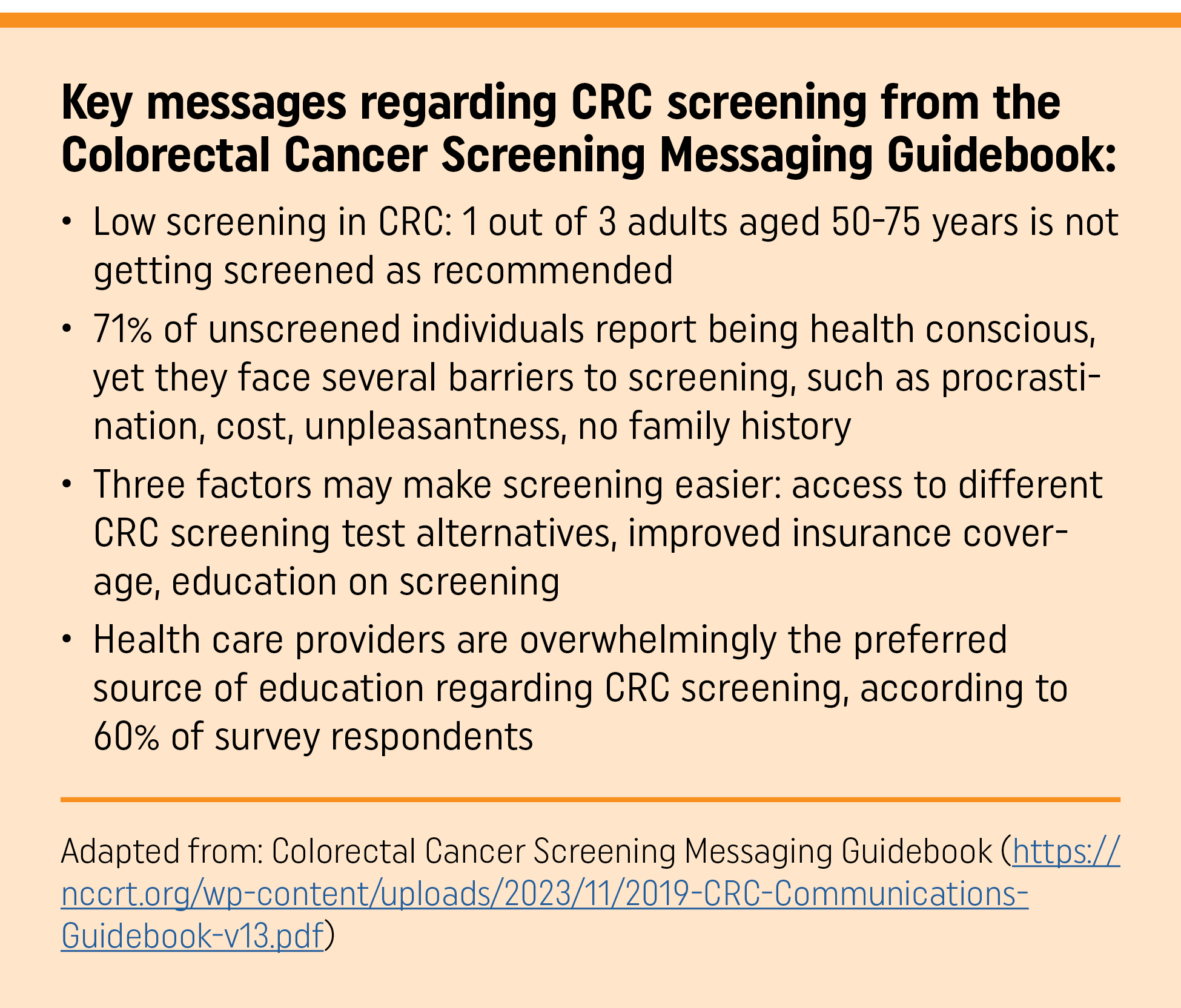

Overcoming Patient Barriers Regarding CRC Screening

Several studies have focused on the identification of barriers to CRC screening amongst different populations. These barriers exist at both the level of the HCPs as well as at the level of patients. For instance, a 2017 study identified a lack of provider recommendation, lack of time to discuss screening, and questions about the efficacy of screening as the primary provider barriers to screening. On the other hand, on the patient side, the study identified barriers such as screening cost, a lack of awareness, lack of health literacy, fear of discomfort, and pain as important barriers. Systemic barriers to the uptake of CRC screening such as a lack of a reminder system, lack of support staff for follow-up, and a shortage of facilities to perform screening are also important3.

Furthermore, on the patient side, belonging to a minority race and ethnicity, and socioeconomic challenges such as a lack of insurance and lower income are factors associated with lower rates of screening and consequently later detection and worse outcomes13. These results have been borne out in a 2019 qualitative study that surveyed patients at primary care sites and a questionnaire that asked the patients to self-report barriers to CRC screening. This study also identified similar barriers as had been identified in national surveys, such as a lack of recommendation from their HCP, fear or worry about the procedure or outcome, financial implications, and logistical challenges, such as transportation and time. Other barriers included a lower health prioritization for CRC screening and concerns about possible discomfort associated with the screening procedure17.

However, it is important to realize that none of these barriers are unsurmountable and can be effectively addressed with patient education and continuing medical education for HCPs on the importance of CRC screening. These include patient literature, such as the 2019 Colorectal Cancer Screening Messaging Guidebook developed by the National Colorectal Cancer Roundtable4. Such literature provides effective communication strategies and facts about the importance of CRC screening to patients that can be easily understood by a layperson4. Moreover, patient education can also be effectively achieved through the development of educational videos, tutorials, and FAQs10. Additionally, providers may make use of reminder prompts in the electronic health records system or use the Colorectal Cancer Risk Assessment Tool provided by the National Cancer Institute (https://ccrisktool.cancer.gov).

Conclusion

CRC is a highly preventable cancer, and the incidence and mortality associated with it can be reduced by implementation of effective screening of patients. Several different screening methods are routinely used in clinical practice to detect CRC. Clinical practice guidelines on CRC screening have been issued by several professional associations in the United States. HCP education regarding these is critical to improving screening amongst target populations, with the ultimate goal of reducing CRC occurrence. Lastly, patient education regarding the importance of CRC screening may be the most effective tool to reducing the incidence of CRC and ensuring adherence to clinical practice guidelines regarding CRC screening.

References

- Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-254.

- Sawicki T, Ruszkowska M, Danielewicz A, Niedźwiedzka E, Arłukowicz T, Przybyłowicz KE. A review of colorectal cancer in terms of epidemiology, risk factors, development, symptoms, and diagnosis. Cancers (Basel). 2021; 13(9): 2025.

- Wang H, Gregg A, Qiu F, Kim J, Young L, Luo J. Provider perceived colorectal cancer screening barriers: results from a survey in accountable care organi-zations. Juniper J Public Health. 2017;1(2):555557.

- NCCRT. 2019 Colorectal Cancer Screening Messaging Guidebook. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://nccrt.org/resource/2019messagingguidebook

- Morgan E, Arnold M, Gini A, et al. Global burden of colorectal cancer in 2020 and 2040: incidence and mortality estimates from GLOBOCAN. Gut. 2023; 72(2): 338-344.

- Chung SS, Ali SI, Cash BD. The present and future of colorectal cancer screen-ing. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2022;18(11):646.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson KW, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation state-ment. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977.

- Ajufo A, Adigun AO, Mohammad M, et al. Factors affecting the rate of colo-noscopy among African Americans aged over 45 years. Cureus. 2023;15(10). https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html

- Kanth P, Inadomi JM. Screening and prevention of colorectal cancer. BMJ. 2021; 374:n1855.

- Chiu HM, Chen SLS, Yen AMF, et al. Effectiveness of fecal immunochemical testing in reducing colorectal cancer mortality from the One Million Taiwanese Screening Program. Cancer. 2015;121(18):3221-3229.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening for Colorectal Cancer—Blood-Based Biomarker Tests. Accessed October 8, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncacal-decision-memo.aspx? proposed= Y&NCAId= 299

- Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, et al. Multitarget stool DNA testing for colorectal-cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(14):1287-1297.

- Pooler BD, Baumel MJ, Cash BD, et al. Screening CT colonography: multicenter survey of patient experience, preference, and potential impact on adherence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(6):1361-1366.

- Ho W, Broughton DE, Donelan K, Gazelle GS, Hur C. Analysis of barriers to and patients’ preferences for CT colonography for colorectal cancer screening in a nonadherent urban population. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(2):393-397.

- Ladabaum U, Dominitz JA, Kahi C, Schoen RE. Strategies for colorectal cancer screening. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):418-432. Accessed October 8, 2025. https://investors.guardanthealth.com/press-releases/press-releases/2024/Guardant-Healths-FDA-approved-Shield-Blood-Test-Now-Commercially-Available-in-U.S.-as-a-Primary-Screening-Option-for-Colorectal-Cancer/default.aspx

- Klabunde CN, Schenck AP, Davis WW. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among Medicare consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(4):313-319.

- James AS, Hall S, Greiner KA, Buckles D, Born WK, Ahluwalia JS. The impact of socioeconomic status on perceived barriers to colorectal cancer testing. Am J Health Promot. 2008;23(2):97-100.

- 18. Sun Q, Long L. Diagnostic performances of methylated septin9 gene, CEA, CA19-9 and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2024; 24:906.

CME Quiz available at https://health.learning.wiley.com/courses/cme-bulletin-crc/ 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ and AAFP Prescribing Credit

For information on applicability and acceptance of continuing medical education credit for this activity, please consult your professional licensing board.

John Wiley and Sons, Inc. is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to provide continuing medical education for physicians. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. designates this enduring material for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™ and AAFP Prescribing Credit. Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

The CME Bulletin is published by the American Academy of Family Physicians, 11400 Tomahawk Creek Parkway, Leawood, Kansas 66211-2680 • www.aafp.org

© 2025 John Wiley and Sons Inc. and all rights for reproduction. Reuse of this material is prohibited without the express written consent of the John Wiley and Sons Inc. in print and online: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774