The authors' success can be a lesson to physician groups as well as residency clinics.

Fam Pract Manag. 1999;06(8):36-40

In the early 1990s, our family practice center, based in a university hospital, was underutilized, inefficient and losing money. We faced problems that are common in many family practice settings today: growing pressure by third-party payers to improve services and efficiency, personnel problems, and an increasingly complex operational and management environment. In addition, we struggled with issues that are all too familiar to residency training sites: competition between educational requirements and clinical demands; the challenges posed by differing levels of expertise among 24 residents; difficulties in scheduling part-time faculty and residents; and related difficulties in maintaining continuity of patient care.

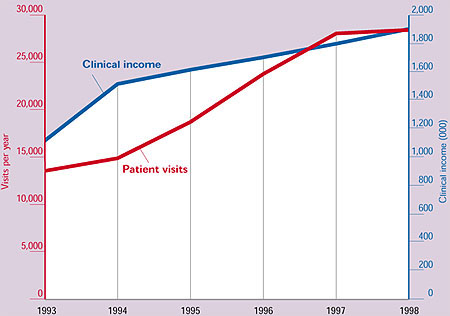

Today, after a five-year re-engineering effort, our number of patient visits has doubled, from 14,000 to 28,000, and our clinical income has increased steadily to the point where it helps support other departmental activities (see “Five years of progress”). Not only do we score consistently high on managed care reports, but, as a result of restructuring, we have reduced our staffing overhead and improved nursing services. Perhaps most important, the practice is no longer considered an unavoidable distraction from our residents' education. Rather, we serve as a model where residents learn to provide high-quality, patient-centered care in an efficient, focused organization.

Key Points:

In five years, the center doubled the number of patient visits, improved services, reduced overhead and improved the education it gave residents.

The authors credit developing a clear mission statement — and using it consistently and communicating it clearly — with sparking the successful reorganization.

Open communication and organizationwide input into the planning of change made the difference between success and failure.

The re-engineering would not have been possible without committed, proactive leadership at all levels.

Getting back to basics

In the early 1990s, leaders in our department recognized the need for improvement and reorganization. The department hired a management consultant, but the results were unimpressive. The department instituted regular team meetings between faculty, staff and residents, but the meetings were poorly planned and, as a result, unproductive. The same lack of planning plagued management meetings, which tended to become rambling discussions. The department set new goals for the practice — such as improving morale and increasing efficiency. They were not, however, defined in measurable terms. In short, our initial improvement efforts were characterized by a lot of talk, but little action.

That changed in 1994 when one of the authors (GEK) was appointed medical director. He sought to improve the ailing organization by focusing on fundamentals. First, he and other department leaders established a core mission for the practice: to provide both high-quality patient care and excellence in teaching residents.

Five years of progress

During the five years since the beginning of their re-engineering project, the authors have watched the number of visits per year and the annual clinical income both climb substantially.

Just as important as articulating a new mission, however, was the decision to make the mission statement the cornerstone of the practice improvement effort. Like many mission statements, ours appeared simple and self-evident. We viewed it, however, as an important summary of our values and priorities, with a number of practical applications. Thus, instead of filing it away to be quickly forgotten, we made a point of communicating our mission clearly and frequently to residents, faculty and staff, both verbally and in writing. As a result, it became a guide for day-to-day administrative and academic decision making, it provided a vision for future planning, and it helped create a sense of pride in our work, which, in turn, helped improve morale across the organization.

A second key step in the improvement process was examining the practice's infrastructure. To create a more functional, streamlined organization, we took a fresh look at the practice's inner workings in three core areas:

Staffing needs. In re-evaluating our staffing requirements, we turned to our newly articulated mission for guidance: What staff resources would best help us meet the needs of patients, faculty and residents? We soon found that, although our clinical staffing accommodated patient care, residents were not meeting the requirements for numbers of patient visits set by the residency review committee. As a result, we initiated a restructuring process. After a series of meetings to gain staff input, the management team decided to replace midlevel providers (who were reassigned within the larger institution) with traditional nursing support staff. As expected, we faced some resistance; but because we maintained close communication with staff before and after the decision was made and because we emphasized the role of this change in achieving our mission, the resistance was short-lived. In addition, staff quickly saw the positive results of the restructuring: additional patient visits for residents and improved phone triage and nursing services for patients.

Organizational structure. Closely linked to our reassessment of personnel needs was an evaluation of our staff structure. Having the right staffing mix would make a difference only if an efficient, effective structure were in place. For many years, the staff had been grouped by function, with nurses reporting to the lead nurse, medical assistants reporting to the lead medical assistant, etc. Employees tended to identify with their small group rather than the organization as a whole, often resulting in an “us against them” mentality.

After seeking staff input, we approached this issue in two ways. First, we replaced the structure of multiple small groups with a less divisive system. Staff — including five FTE receptionists, two FTE file clerks, six FTE medical assistants and up to two FTE lab personnel — now report to the clinical supervisor, while clinicians (physicians and 2.5 FTE nurses) report to the medical director. The clinical supervisor and the medical director work closely on personnel issues: Each handles day-to-day employee matters and, although the medical director has final authority on hiring and firing, such decisions are typically made jointly by the two managers.

The restructuring was intended to build a sense that everyone in the practice is part of the same team, so it was important that it be implemented in an open, inclusive manner. We used staff meetings to introduce the new model and address staff concerns. This allowed us to keep staff involved in the process and provided a forum for communication. As a result, although the transition was not without difficulties, our new structure was soon a well-accepted part of daily life at the practice.

Our second step in strengthening the organizational structure was to develop a policies and procedures manual. The manual, which guides clinical and management operations for staff, faculty and residents, reflects our “one standard for all” philosophy. For example, determinations about physician time off had been made inconsistently, based on an unwritten policy. We developed formal guidelines that not only outline specific steps for requesting time off but hold faculty and residents to the same high standards in arranging for coverage and ensuring that patient care is not disrupted. The policies and procedures manual thus serves as a source of information for employees and a tool to ensure that the staff is managed fairly and consistently.

Scheduling. One of our most crucial infrastructure changes was in clinical scheduling for residents and faculty. In the past, we produced separate monthly schedules for each clinical function: patient care, precepting, nursing home visits, inpatient service, etc. To gain a complete picture of a resident's or faculty member's clinical schedule, one had to consult several pieces of paper. And because the center had no mechanism for regularly updating the schedules between monthly publications, they quickly became outdated. Clearly, we needed a new scheduling process — one that was detailed, adaptable and reflective of our commitment to both patient care and teaching.

The medical director, working with the residency coordinator, developed a one-page weekly scheduling form that incorporates all patient care and precepting activities for the entire practice (see “One schedule for everything”). Weekly schedules are prepared approximately three months in advance, based on predetermined annual schedules for patient care, call and residency rotations. Information from the annual schedules is combined with written requests for time off and schedule changes by the residency coordinator; reviewed and approved by the medical director; distributed to clinicians, faculty and administrators; and posted at the practice. To ensure that schedules stay current once they've been published, the residency coordinator and the scheduler at the practice communicate closely, jointly updating and revising existing schedules every week. The result is a snapshot of clinical activities that is accurate, concise and easy to use.

One schedule for everything

The authors helped relieve scheduling chaos in the family practice center by developing a one-page weekly schedule form that could show the center's complete clinical schedule at a glance. A portion of one week's schedule is reproduced below.

| Mon 22 | Tues 23 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Care | AM | Abdallah | Conn |

| Crownover 8:30-11:45 | Dorr | ||

| Edwards 8:00-11:15 | Ford | ||

| Ford | Joy | ||

| Joy | Hamrich | ||

| Podl | Kale | ||

| Rowane 8:30-11:45 | Lacy | ||

| Wagstaff 8:00-11:15 | Marsh 8:30-11:45 | ||

| Moore 8:30-11:45 | |||

| Wagstaff 8:00-11:15 | |||

| Patient Care | PM | Abdallah | Crownover 1:00-4:15 |

| Ford (Sick) | Dorr | ||

| Hamrich | Edwards 1:00-4:15 | ||

| Kale | Frank 1:00-4:15 | ||

| Kikano 1:00-4:15 | Kale (Sick) | ||

| Lacy 1:30-3:45 | Mohammed | ||

| Marsh 1:00-4:15 | |||

| Podl | |||

| Resnick | |||

| Wagstaff | Cadesky Grn Rd | ||

| Patient Care | Evening | Conn | |

| Kikano | |||

| Podl | |||

| Podiatrist | |||

| Precepting | AM | Chao | Cadesky |

| Sobey | Sobey | ||

| Precepting | PM | Cadesky | Kikano |

| Rowane | Wagstaff | ||

| Nursing Home | AM | Marsh/Kale McG | |

| Nursing Home | PM | Christie AS | Christie McG |

| Family Practice Inpatient Service/Call | Stange | Stange | |

| Chao OB | Rowane OB | ||

| Mohammed SAR | Mohammed SAR | ||

| Hussny Intern | Hussny Intern | ||

| Zhang PI | Zhang PI/NF | ||

| Veregge NF | |||

| Other | |||

| Conferences | 8:00 Morning Report | 12:30 Pract Mgmt | |

| Unavailable | Acheson | Acheson | |

| Graham | Graham | ||

| Jandi | Jandi | ||

| Keller | Keller | ||

| Morikawa | Morikawa |

The schedule is both flexible and firm. It is flexible because we can adapt it to our actual needs. For example, scheduling an adequate number of faculty to precept per half day is a dynamic process. We need adequate coverage based on the number and level of learners per session while maintaining an adequate number of clinical providers to cover patient-care needs. Our scheduling format allows us to adjust the numbers of faculty and providers for a given week to meet our changing educational and clinical needs. The schedule is firm, however, in that commitments are not easily changed. Clinicians can cancel scheduled patient-care appointments only for urgent reasons, and they are encouraged to make up the time during the same week. Faculty can cancel precepting sessions only if they find coverage from another faculty member. This sends an important message to our faculty and residents: Patient care and teaching are our two priorities.

Continuing to learn

Our re-engineering effort has been an ongoing learning process. Three of our most important lessons have been about communication, leadership and the changing health care environment.

Talk is talk, but communication makes a difference. Our early attempts at change were characterized by a lot of talk but little meaningful communication. As we continued our efforts and undertook significant change, we realized that open, clear sharing of information was essential if our changes were to succeed.

In some cases, improved communication came about as a byproduct of other changes: Rewriting and disseminating policies and procedures, for example, gave all of us a clearer understanding of roles, expectations and decision- making channels within the practice. We also implemented efforts specifically designed to improve communication. To ensure practice-wide input into the change process, we involved faculty and staff in identifying the needs of the practice and making decisions about appropriate uses of resources. Once a change was in place, we asked those who were affected to provide feedback and, if necessary, to help make modifications.

By incorporating opportunities for communication into the change effort, we benefited on a number of levels: Faculty and staff, knowing that their input made a difference, gained a sense of ownership in the process; and those of us overseeing the change effort benefited from receiving broad-based, diverse input that helped ground our decisions in the realities of practice.

Leadership takes many forms. The reengineering process involved strong leadership on several levels:

The department chair set a tone of support for the effort. He gave the medical director full authority to make practice-change decisions and supported our efforts.

Faculty served as effective leaders and role models. Their leadership was especially important as we worked to “level the playing field” between junior faculty, senior faculty and residents. For example, faculty supported the implementation of policies that held them to the same standards as residents in requesting time off, completing medical records and returning patients' phone calls. This effort to improve our team environment meant eliminating double standards in practice management and administration. Now, faculty members teach and lead by example in an atmosphere of shared learning and responsibility.

The medical director has seen his role as championing the practice improvement effort, striving to reinforce the mission, goals and objectives despite resistance. His intent has been to keep the providers and staff focused on both short- and long-term improvement goals.

Be proactive, not reactive to the health care environment. Our efforts to strengthen the practice have focused on the external health care environment as well as our internal operations. This has helped us anticipate coming trends, new guidelines and shifting priorities. For example, by serving on institutional and managed care organization committees, we have gained first-hand knowledge about upcoming reviews and incentive plans. Also, whenever possible, we align the practice's goals with those of our institution. If the hospital undertakes a prevention initiative, for example, we make every effort to participate, allowing us to build on the institution's momentum. Being aware of and involved in the external environment has allowed us to plan for, rather than simply react to, changes in the health care system. We are also better equipped to prepare our residents for the world in which they will practice.

Helping change succeed

Given the clinical and organizational complexity of family practices, and especially family practice centers, changing them can be daunting. Two approaches helped us make change more manageable and successful. First, we focused on fundamental concepts: a clearly articulated mission and goals, solid infrastructure, and the flexibility to balance educational and service needs. Second, we viewed change — both within our organization and in the health care environment — not as a barrier, but as an opportunity to strengthen our workplace and serve our patients better.