Findings from the Future of Family Medicine project suggest the New Model could boost your income or enable you to work fewer hours.

Fam Pract Manag. 2005;12(5):68-72

The Future of Family Medicine project was initiated in 2002 with the goal of transforming and renewing the specialty of family medicine to meet the needs of people and society in a changing environment. The initial project report, based on the work of five different task forces, was published in March 2004 and included 10 specific recommendations “intended to provide a framework to guide a period of active experimentation and innovation within the discipline.”1 The first of these recommendations is that “family medicine will redesign the work and workplaces of family physicians,” fostering a New Model of family medicine. (The article on page 59 describes the New Model.)

The initial report also recommended the creation of an additional task force with two specific goals: 1) to develop a financial model that assesses the impact of the New Model on practice finances, and 2) to recommend health care financial policies that, if implemented, would promote the New Model and the primary medical care function in the United States over the next few decades.

This group, Task Force Six, engaged the Lewin Group as consultants to assist with developing the microeconomic (practice-level) and macroeconomic (societal level) financial models necessary to achieve its goals. The consultants conducted two types of analyses. First, they simulated the impact of the New Model on a family medicine practice within the current fee-for-service reimbursement environment. Second, they analyzed alternative reimbursement mechanisms for the New Model to estimate their impact on family physicians' practices. Task Force Six published its full report in November 2004.2 This article describes the key findings.

KEY POINTS

The New Model of family medicine, suggested by the Future of Family Medicine project, is estimated to increase family physician compensation by 26 percent.

Under enhanced reimbursement systems, physicians' compensation could rise 61 percent to an estimated $277,800.

To receive better reimbursement for their services, family physicians must demonstrate that they add value to the current health care system.

The financial model

The microanalysis examined the impact that implementing New Model features would have on practice expenses and revenues. The task force identified 10 features of the New Model that could have a direct effect on practices and that are most amenable to modeling:

Open-access scheduling;

Online appointment scheduling;

Electronic health records;

Group visits;

E-visits (i.e., brief patient visits facilitated by e-mail);

Chronic disease management;

Web-based information;

Team approach, where clinical staff are more involved in providing care;

Use of clinical guidelines software;

Outcomes analysis.

For each feature of the New Model, the task force considered its impact on a practice in the following areas:

Up-front training requirements;

Number of services performed;

Service intensity (i.e., revenue or relative value units per procedure);

Physician time per service;

Clinical staff time per service;

Office expenses (e.g., information technology, facility and equipment costs);

Administrative staff costs;

Malpractice premiums.

The financial model was developed using information available from the medical literature, numerous practice management databases, AAFP physician surveys and interviews with certain physicians who have already implemented features of the New Model in their practices.

The model is based on pretax income benchmarks of $142,338 (or $167,457 including benefits) under the current reimbursement system for those in a five-physician practice. This figure approximates the average annual income of $140,500 reported by family physicians responding to the 2004 AAFP Practice Profile Survey. It also assumes an average work week of 51 hours, with 40 of those spent in direct patient care.

The model estimates a slightly higher average income for physicians in larger practices. For example, for a three- and a seven-physician practice, the model estimates average physician incomes of $138,199 and $144,112, respectively.

The impact under today's reimbursement system

The table shows the impact the New Model would have on a five-physician practice under the current reimbursement system. It predicts significant potential increases in income as a result of implementing designated features of the New Model. A full-time physician could increase total income by 26 percent if all features of the model were implemented and the physician continued to work the same number of hours. Alternatively, a full-time physician could reduce work hours by 12 percent and maintain his or her current level of income, or reduce work hours by 18 percent and earn 12 percent less income.

The cost of transitioning from the existing model of care to the New Model was also considered. These costs will vary by practice and include the following:

Initial purchase price of necessary equipment and supplies (i.e., capital costs);

Recruiting new personnel as needed;

Training existing personnel;

Lost productivity.

These are up-front, one-time costs (both direct and indirect) required to move from the current practice to the New Model. They do not include other costs associated with the New Model (e.g., maintenance of the EHR, performance of outcomes analysis), which are already accounted for in the microeconomic analysis above.

Transition costs were estimated to range from $23,442 to $90,650 per physician for a five-physician family practice. Actual costs depend on the loss in physician productivity during the first year of implementation of the New Model (estimated to range between 5 percent and 20 percent). While transition costs may absorb some of the initial financial gains associated with the new model, they are temporary and will not affect future gains.

ESTIMATED IMPACT OF THE NEW MODEL ON PHYSICIAN COMPENSATION

| Change in compensation per physician | ||

|---|---|---|

| Feature of New Model | With 18-percent reduction in hours worked | With current work hours |

| Open-access scheduling | $9,133 | $9,133 |

| Online appointment scheduling | $5,752 | $5,752 |

| Electronic health records | $3,398 | $15,573 |

| Group visits | ($8,769) | $15,411 |

| E-visits | ($7,649) | ($3,786) |

| Chronic disease management | ($8,591) | ($10,435) |

| Web-based information | ($2,000) | ($2,000) |

| Leveraging clinical staff | ($6,121) | $9,699 |

| Clinical practice guidelines software | ($3,877) | $5,664 |

| Outcomes analysis | ($2,180) | ($2,180) |

| Change in compensation with New Model | ($20,904) | $42,831 |

| Average total compensation per physician under current reimbursement system | $167,457 | $167,457 |

| Total compensation per physician under New Model | $146,553 | $210,288 |

| Percent change | −12% | 26% |

The impact under enhanced reimbursement systems

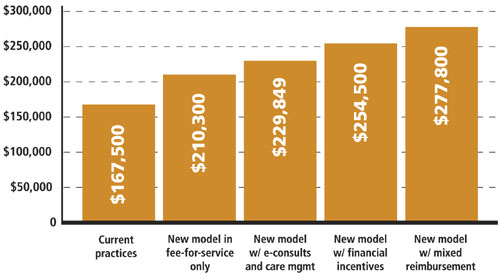

Macrolevel analyses were conducted to determine how reimbursement innovations that reward performance would affect practices that implemented the New Model of Family Medicine. The graph shows estimates of average family physician compensation under the varying reimbursement systems described below.

For example, the macroanalysis assumes that e-visits would be reimbursed at $25 per visit, not to exceed 25 visits per patient per year, and that chronic disease management would be reimbursed at $15 per patient per month, with 10 percent of the average physician panel of 2,030 patients receiving this type of care. The resulting additional compensation for family physicians maintaining the current number of work hours assumed in the model would be $4,715 for e-visits and $14,834 for chronic disease management. The additional compensation for family physicians reducing work hours by 18 percent would be $4,631 for e-visits and $12,213 for chronic disease management.

Another reimbursement innovation would be to offer physicians financial incentives, such as those that health plans who participate in the Bridges to Excellence program (http://www.bridgestoexcellence.org/bte) offer:

1. Physician Office Link enables physicians to earn up to $50 per patient, up to a cap of $20,000 annually, based on implementation of specific processes for improving quality including the following:

A $25 payment per patient for investing in an EHR system, with the payment phased out over three years as the EHR becomes established;

A $5 payment per patient for establishing patient education programs;

A $10 payment per patient per year for case management.

2. Diabetes Care Link enables physicians with high performance in diabetes care to earn $80 per eligible patient per year;

3. Cardiac Care Link enables physicians with high performance in cardiac care to receive up to $160 per eligible patient per year.

Physicians who qualify for these bonuses could add up to $44,200 of total compensation per year. This estimate assumes that the costs of achieving these high-quality services are embedded in the cost of adopting the New Model, as discussed above. It assumes that the physician earns the maximum bonus under the Physician Office Link program (i.e., $20,000) and that 7 percent of the physician's patient panel has diabetes and about 3 percent have qualifying cardiac conditions.

Another approach to funding the New Model is to rely upon a mix of reimbursement methods. Under this approach, fee-for-service reimbursement would remain the primary form of reimbursement. However, physicians would also receive from insurers a fixed annual payment for each patient in their panel to fund the cost of adopting the New Model. The per patient fee (estimated at $10 per patient per year in this scenario) is designed to recover the costs associated with providing the higher level of care and service under the New Model and would amount to $20,300 for an average physician with a patient panel of 2,030. This amount nearly covers the reduction in net compensation for physicians who choose not to increase their patient volume. Bonuses such as those featured in the Bridges to Excellence program would also be included, as well as other bonuses based on patient satisfaction surveys, HEDIS measures, use of generic prescriptions and other measures negotiated with participating physicians. It is assumed that the maximum bonus would be $20,000 per physician per year. Some health plans already have bonus systems with comparable maximum bonus potential.

Within this mixed reimbursement system, physician compensation could increase substantially, particularly for those who use the efficiencies of the New Model to provide care to more patients. Compensation would increase between $66,100 and $110,300 depending on the bonuses earned under the system. If all of the described changes in reimbursement were implemented, total average compensation would rise 61 percent to an estimated $277,800. (Again, see the graph.)

While the New Model would increase reimbursement for family medicine, it would likely result in savings for employers and health plans. True integration of care, improvements in patient safety and monitoring of chronic care have the potential to reduce spending for hospital care and other specialty care. Moreover, it is widely documented that patient care costs are reduced when people obtain their primary care through primary care physicians rather than other specialists.3

PHYSICIAN COMPENSATION UNDER ALTERNATIVE REIMBURSEMENT MODELS

A family physician in a five-physician group earns an estimated $167,500 in total compensation per year under current reimbursement models. Roughly 15 percent of compensation goes toward benefits, with the remainder as income.

Implementing the New Model can increase a family physician's total compensation to $210,300. Improved reimbursement models would result in further increases, as shown here.

Source: Lewin Group estimates.

Implications for the specialty

The findings of the Future of Family Medicine Task Force Six have important implications for the specialty of family medicine. The financial modeling exercises suggest that the New Model of family medicine should be financially viable under the current fee-for-service reimbursement system and would be even more viable and profitable under a new, mixed model of reimbursement. These results need to be tested in vivo, in the real world of practice.

Family physicians will need assistance implementing the New Model features in their practices. It is currently not possible to purchase off the shelf all of the technology and know-how necessary to implement the New Model in a turnkey fashion. Following the recommendations of Task Force Six, the AAFP Board of Directors has voted to establish a subsidiary company to serve as a New Model Practice Resource Center and support the implementation of the New Model in family practices across the country. The first phase of work for this new center will be to conduct a national demonstration project to test the concept of the New Model in 20 diverse practices with wide geographic distribution.

To receive better reimbursement for their services, family physicians must demonstrate that they can add value to the current health care system. To do so, they must be willing to take risks, change and reinvent themselves through the implementation of the New Model. They must carefully measure the processes and outcomes of their care to document its quality. The specialty will need to develop creative methods of financing the necessary capital investments to help family physicians afford the transition costs. And family physicians may need to join their practices together, however loosely, for the purpose of gathering data to be used in negotiating more favorable reimbursement rates from health care insurers.

Achieving widespread implementation of the New Model of family medicine will not be easy. And yet the long-term viability of the specialty, and the well-being of our health care system and population, is at stake.