A recent survey of active AAFP members found some surprising results.

Fam Pract Manag. 2005;12(7):16-20

Family physician income will always be a high-interest subject, at least among family physicians. Surveys from the AAFP and other groups show how the average family physician's income has changed over time (see “Average income”), but they don't tell the whole story.

While conducting a focus group with family physicians about three years ago, I started exploring family physician incomes in more depth. Several full-time practicing family physicians in the group said they were making $80,000 or less. Yet I knew of others who made more than $250,000. Why the difference?

AVERAGE INCOME

Data from the AAFP's annual Practice Profile Survey show the ups and downs in active members' mean income from practice before taxes. The survey includes family physicians in part-time practices.

| Year | Income |

|---|---|

| 1993 | $146,000 |

| 1994 | $150,000 |

| 1995 | $161,000 |

| 1996 | $160,000 |

| 1997 | $154,000 |

| 1998 | $151,000 |

| 1999 | $148,000 |

| 2000 | $146,000 |

| 2001 | $141,000 |

| 2002 | $146,000 |

| 2003 | $141,000 |

Drilling into the numbers

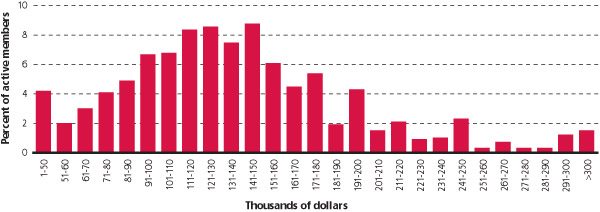

To begin this investigation, I analyzed the compensation reported in AAFP demographic surveys of members defined as “active.” This includes people just entering practice, those gearing down for retirement and those working part-time. I found a wide distribution of family physician incomes (see “Distribution of incomes”).

A regression analysis and predictive segmentation modeling effort in early 2004 by Greg Tolleson, the AAFP's manager of data analysis and collection, showed that the best predictors of high member income are a high number of office visits per week, being male and providing emergency and obstetric services.

We thought there were more factors at work. In the middle of 2004, Kathy Reid, the AAFP's manager of organizational marketing research, and I worked with other staff to develop a survey that would identify factors that distinguish high-earning family physicians. After testing with the members of the AAFP's Commission on Health Care Services, we sent the survey to 1,748 active AAFP members who had been out of residency five years or longer and worked at least 40 hours per week. From one mailing, 730 surveys were returned for a response rate of 41.8 percent. We then grouped the respondents into “high-earners” (those with 2003 pre-tax individual incomes of $160,000 after expenses from their medical practice) and “low-earners” (those with 2003 pre-tax individual incomes of $100,000 or less after practice expenses).

DISTRIBUTION OF INCOMES

What made the difference?

Some of the results surprised us. (See “What makes a high-earner?”)

The strongest influence on physician income – number of patient visits – makes sense in today's environment, in which physicians are paid on a piecework basis. The high-earners saw a mean number of 122 patients per week compared to 84 for the low-earners. But practicing the full scope of family medicine in the hospital setting, the second most influential factor among high-earners, was a surprise. The AAFP has long encouraged the full scope of family medicine but had never before tied it to income. And the third-ranked factor – being in a larger practice – is a departure from conventional wisdom, which used to predict that family physicians in smaller practices would make more money.

The factors that did not make a significant difference in family physician income were similarly surprising. (See “Low-impact factors on income.”) These include many of the strategies that are traditionally taught in practice management: frequent staff meetings, staff training, capitation, collecting co-pays and attention to account aging.

Throughout our study of family physician incomes, we have seen a lot of internal consistency. Both our internal retrospective study and the more recent survey of active members indicated that the biggest influence on income was the number of patient visits. Moreover, survey respondents' open-ended comments regarding what made the difference in income echoed what we found in the quantitative data.

But there are some disturbing findings among the studies. Most notably, gender differences in income remain. Studies in other journals such as the Journal of the American Medical Women's Association show that female family physicians tend to make less than men, even when corrected for workload, age and type of practice.1–2 In addition, sharp regional differences in income continue, with family physicians in the West South Central Census Division (Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Texas) making the most and those in the Northeast making the least.

WHAT MAKES A HIGH-EARNER?

A 2004 survey of active AAFP members who were out of residency five years or longer and worked 40 hours per week or more indicated that the following factors, listed in order of importance, are associated with high-earning family physicians (e.g., those earning $160,000 or more, compared to those earning $100,000 or less).

Providing more patient visits (high-earners saw a mean number of 122 patients per week; low-earners saw 84);

Practicing the full scope of family medicine in the hospital setting;

Being in larger practices (which may be related to the next four factors);

Providing clinical lab, physical therapy, occupational therapy and imaging services in-house;

Viewing negotiations with payers and evaluating contracts as very important;

Participating in quality improvement, marketing, strategic planning and benchmarking;

Having in-house billing and collections;

Seeing more Medicare patients (nationally, may vary by state);

Working more hours;

Being paid based on productivity;

Planning to purchase an EHR.

LOW-IMPACT FACTORS ON INCOME

A 2004 survey of active AAFP members found that the following factors did not make a significant difference in family physician income:

Current use of an EHR;

Number of staff meetings;

Practice management courses for physicians or staff;

Educational level of in-house billing staff;

Fee-for-service versus capitated revenue;

Percentage of co-payments collected at the time of service;

Aging of accounts receivable.

What you can do now

There are a number of things you can you do if you want to make more money:

See more patients. The difference between high-earners and low-earners averaged eight patients per day.

Work for changing the health care system to ensure that primary care, prevention and high quality are explicitly recognized and financially rewarded.

Read the report of the Future of Family Medicine Task Force Six, published online at http://www.annfammed.org/cgi/content/full/2/suppl_3/s1. The report offers an economic model that, even under the current reimbursement system, is projected to increase family physician income.

Include hospital care in your scope of practice.

Consider expanding your practice's size to take advantage of economies of scale and other factors (e.g., in-house billing and collections).

Evaluate contracts carefully before signing. Do not sign a bad contract.

Look for ways to increase the number of patients you see who are insured by the best-paying health plans.

In the meantime, AAFP's staff will continue these investigations to find more information that can help family physicians earn more.