Sometimes the best way to solve our patients' medical problems is to make sure they're taking their medicine.

Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(2):25-30

Author disclosure: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

One of the most effective medical interventions to significantly improve the health of your patients doesn't require the latest technology or expensive medication but simply involves helping them take their existing medication as prescribed.

“Increasing the effectiveness of adherence interventions may have a far greater impact on the health of the population than any improvement in specific medical treatments,” according to the World Health Organization.1

Consider, for example, an efficient office practice with a team dedicated to performing medication reconciliation at each visit. First, the patient is asked to list his or her medicines. The medical assistant or nurse then reviews the medications, asks which ones need refills, inquires about any side effects, ensures inclusion of any new medication prescribed by other doctors as well as complementary and alternative drugs, checks to see if the patient can afford his or her medications, and offers to answer any questions about the medicines. Very thorough, right?

Yet, during this extensive evaluation, the patient was never asked if he or she was actually taking the medicines.

Mrs. Sullivan, a new patient to my [Dr. Brown's] practice, told me on her first visit that she was taking three drugs for Type 2 diabetes. She was an obese 40-year-old with a recent A1C of 10. While in the waiting room, she listed her medications: insulin, metformin, and a sulfonylurea. In the exam room, the medical assistant reviewed the patient's medications, including frequency and dosing. Because the patient's drug regimen was apparently not working, I faced adding a fourth drug or increasing her insulin, which would most likely also increase her weight.

I had just read an article on medication nonadherence, so instead of escalating therapy I paused and asked if she actually took her medications.

“Yes,” she replied.

“Do you take them every day?” I asked.

She said yes again and denied that there were days when she would skip.

I wondered what I was missing.

“When was the last time you took your medicine?” I asked.

She replied, “Three months ago.” Aha!

When I asked her why, she said her insurance had changed and she didn't have a doctor. So, in her mind, she took her medicine every day – when she had it.

Patients don't take their medicine 50 percent of the time.2 Approximately a quarter of all prescriptions are never even filled.3,4 Approximately half of all medication-related admissions are due to nonadherence.2 All of this nonadherence adds up to an estimated $100 billion in preventable health care costs.

Nonadherence isn't a new problem. Hippocrates wrote, “Keep a watch ... on the faults of the patients, which often make them lie about the taking of things prescribed. For through not taking disagreeable drinks, purgative or other, they sometimes die.”

In our current “pay for performance” environment, physicians have added reason for frustration as patients' nonadherence, with its resultant uncontrolled blood pressures and elevated A1Cs, reflects poorly on the provider and affects the practice's finances. Worse, the nonadherent patient can become an adversary rather than a partner in his or her own care.

Medication-taking behavior is complicated. Our experience and our reading of the literature lead us to suggest the following five steps to help patients improve their medication adherence:

1. Ask the question … but don't shoot the messenger

In the future, with more sophisticated and interoperative data sources and with hopefully greater funding of primary care to help cover additional staffing costs, more practices may be able to improve adherence by monitoring prescription refill rates and dedicating staff to respond.

In the meantime, you'll have to rely on questioning your patients.

How you ask the question matters, because patients generally want to please their doctor. Asking, “You take your medicine every day, don't you?” leaves little room for an honest, negative answer. (The subtext is “You wouldn't be foolish enough not to take your medicine as ordered, would you?”) In general, people are more comfortable answering questions in the affirmative.

Consider these examples:5

When you feel like your blood pressure is under control, do you sometimes stop taking your medicine?

Taking medication every day is a real inconvenience for some people. Do you ever feel hassled about sticking to your blood pressure treatment plan?

How often do you have difficulty remembering to take all your blood pressure medication?

A common reaction to nonadherence is to “scold and scare” patients by listing the horrible conditions looming in their future. In response, patients often feel shamed and that they have done something wrong. They learn quickly not to reveal nonadherence for fear of invoking the same unpleasant response from the provider, and the cycle continues. Patients may even practice “white coat adherence” by taking medication as prescribed for the week before their visit or hiding their nonadherence completely.

When patients reveal nonadherence, it is important to assure them that it is a positive step that they felt comfortable telling you. Emphasize that now you can work together to identify the challenges and decide how to achieve mutually agreed-upon goals.

2. Develop a differential diagnosis of nonadherence

You might assume that forgetfulness accounts for most nonadherence. But in fact more than 200 reasons are commonly given for nonadherence, and “forgetting” accounts for less than 30 percent of the phenomenon.2 Most nonadherence is intentional (see “Differential diagnosis of nonadherence”). Patients make rational decisions to not take the medicine as prescribed based on their knowledge and values.

For example, patients may have been frightened and confused by media reports of drugs such as hormone replacement therapy, thiazolidinediones (TZDs), and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that were once considered safe but are now considered ill-advised or dangerous or have even been pulled off the market. This shakes their confidence and reduces their trust in our recommendations. Furthermore, patients may assume that physicians prescribe certain drugs because they receive financial or other kinds of incentives from drug companies, an impression encouraged by sitting in the waiting room next to a drug representative.

Health literacy plays a key role as well. It is difficult for patients to take a medicine when they do not understand why it is prescribed, what conditions or diseases it treats, or what preventive effects it provides.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF NONADHERENCE

| Unintentional | Intentional |

| Forgetting Shift work Confusion Work restrictions Mental illness | Mistrust Fear of side effects (actual or perceived) Cost Mental illness Lack of belief in benefit Fear of dependency Fear that medication is dangerous Lack of desire No apparent benefit |

3. Tailor the solution to the problem

It is important to tailor the adherence solution to the nonadherence problem. In the asymptomatic patient, for example, understanding the patient's perspective is vital. Empathetic comments, such as “It is difficult to take a medicine when you don't feel any different whether you take it or not,” build a trusting relationship and allow the discussion to continue.

Many patients are motivated by immediate rewards rather than benefits linked to long-term therapy. This phenomenon has been labeled “the impatient patient.”6 This concept was highlighted for me (Dr. Brown) during my care of a patient with diabetes and hypertension who had been prescribed four daily insulin injections along with several other drugs. She listened attentively to my passionate description of the complications of diabetic retinopathy that awaited her in the distant future if she didn't control her blood sugar. She agreed her sugars needed much better control and became adherent for a few months. But she eventually stopped her medications and her A1C fluctuated over the years between seven and more than 10.

After many frustrating visits, I noticed that she was wearing new, expensive glasses. Searching for something the patient and I might agree upon, I complimented her on the attractive eyewear. She shared her frustration that her favorite fashionable glasses did not always correct her vision and each time she went to the eye doctor for corrective lenses, he prescribed a new, costly prescription. Rather than stressing the future risk of retinopathy, I explained the connection between her fluctuating glucose readings and her refractive error, which motivated her to maintain her blood glucose levels at goal and avoid paying to continually update her designer eyeglasses.

THE THINKING OF THE “IMPATIENT PATIENT”6

| 1. The nonadherent patient prefers immediate rewards to efforts linked to long-term therapy. |

| 2. Most people have an innate tendency to prefer smaller-sooner to larger-later rewards. |

| 3. The reward of adherence in the management of chronic disease is “to avoid complications.” Paradoxically, this type of reward is never “received.” |

| 4. Doctors are future-oriented while some patients may not consider themselves as having a future. |

4. Prescribe the right drug at the right dose

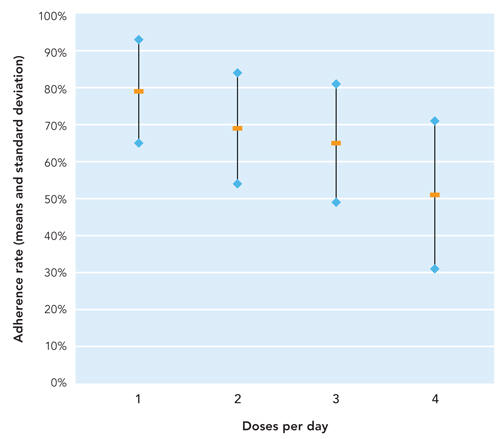

Taking single daily doses is far easier for the patient on lifelong therapy. Osterberg highlights the association between frequency of dosing and adherence, showing an almost 10 percent decrease in adherence with each additional daily dose.2 (See “Adherence decreases as the number of doses per day increases.”)

ADHERENCE DECREASES AS THE NUMBER OF DOSES PER DAY INCREASES2

Look for extended-release formulations, recognize that not all statins need to be taken in the evening, or use “forgiving drugs” – those with longer half-lives, fewer side effects if discontinued, or weekly or monthly dosing. (See “Barriers and solutions for common medications.”) For example, as only 40 percent to 70 percent of patients adhere to their antidepressants,2,7,8 a long half-life drug such as fluoxetine may be more effective for patients who frequently miss doses.

Polypharmacy (use of multiple medications for numerous chronic diseases) increases the risk of medication nonadherence as well. Using the fewest number of medications at the lowest frequency can reduce the “pill burden” – the number of tablets, capsules, inhalers, and other medication that a patient takes or uses on a regular basis. This should always be the goal. It is rewarding to find a way to discontinue a medication or simplify the regimen, and patients greatly appreciate this.

Providers need to tell patients how long they will be required to take many of their medications, especially if it's expected to be for years or even for the rest of their lives. It's a step relatively few physicians take. In a study looking at prescribing behavior, family physicians were more likely than cardiologists to inform patients of duration, but still at a low rate of 33 percent versus 19 percent.9

Some electronic health record (EHR) systems auto-populate prescriptions with directions of “one every day for three months.” Why wouldn't a thoughtful person, not knowing otherwise, stop the medicine after only three months? Besides improving accuracy, these discussions can make patients feel more informed about their care, which studies have shown also increases adherence.9

In the case of Mrs. Sullivan, I discussed her medication-taking behavior with her. I pointed out that if she took her metformin every day, she might not need the other medications. She was thrilled to think we could stop some of her medicine. I instructed her that if she developed diarrhea she could decrease her metformin to the previous dose and then, when she was comfortable and the symptoms resolved for five to seven days, she could increase it. She took charge of escalating her dosage and successfully achieved the maximum dose for the first time within a few months. With encouragement and slow, careful titration of her metformin, she achieved an A1C of seven, no longer needed insulin or sulfonylureas, and lost weight. She also discovered that if she took a drug holiday as short as three days, she needed to restart her titration to avoid diarrhea. Now she never misses a dose.

5. Involve the team

Educating the team about medication adherence is critical. Patients may be more comfortable confiding in the nonphysician staff, but only if the result is an understanding provider who will address the information and not “reprimand” the patient.

During a recent staff meeting discussing a patient's uncontrolled A1C, LDL levels, and blood pressure, both physicians and staff took the easy out of blaming the patient for not taking or understanding his medication. However, in searching for solutions to the problem, we also recognized it would be helpful if the patient brought in his medication at each visit. Our receptionist, listening to our frustration and complaints, suggested that she add “Please bring in all your medications, even the ones you are not taking, medications from other doctors, and all nonprescription medications” when she made reminder phone calls the day before patients' appointments.

BARRIERS AND SOLUTIONS FOR COMMON MEDICATIONS

| Medication | Usual barrier | Best solution |

| Diuretics | Urinary urgency | Allow patient to choose when to dose. |

| Metformin | Diarrhea | Reassure patient that diarrhea will resolve within seven days. Explain that diarrhea will return if patient is nonadherent for as few as three days. |

| Antidepressants | Discontinuation symptoms | Prescribe long-acting drug(e.g., fluoxetine) that will be less likely to cause discontinuation symptoms. |

| Antiplatelet drugs | Bruising | Share with patient that this means the drug is working. |

| Statins | Patient misses evening dose | Advise patient to take statin with other daily medications rather than skip doses, and if needed adjust dosage. |

The addition of this simple four-second message, which could be added to an automated reminder, conveys to the patient that we recognize that they may not be adherent and may be taking complementary and alternative drugs. This intervention assisted the clinical staff in identifying nonadherence and uncovered medication errors as well. Now the front-desk staff hands patients a list of their medications, generated by the EHR, and requests that they cross out the ones they are not taking, circle the ones that require refills, add any new medications, and put a question mark next to a medication that they have questions about. This engages patients in their own health care.

Patients are more likely to confide their fears of side effects, inability to afford the medication, and other medication-taking behavior if they have a long-standing, trusting relationship with their provider. That trusting relationship requires time, which is well spent, as every dollar spent improving medication adherence saves $7 in care.10

In summary, nonadherence is so commonplace that if a patient's readings for blood pressure, LDL, or A1C are not at goal, we now assume the patient is not taking his or her medicine and we proceed with a different type of evaluation than we did in the past. We now consider a differential diagnosis of nonadherence rather than automatically diagnosing a resistant condition. Helping to find the unique solution to our patients' nonadherence has saved lives, spared us from frustration, saved us time, and brought more joy to our individual practices.11