When capable nurses are given greater responsibility for each patient encounter, good results follow.

Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20(4):18-22

Author disclosure: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

After completing my family medicine residency a few years ago, I immediately joined a private group practice with eight family physicians and two nurse practitioners and inherited a nearly full patient panel from a retiring family physician. I naively assumed that transitioning from residency to private practice would decrease my workload and increase my quality of life, but after a hectic first year, I knew that something had to change for my professional life to be sustainable. I was spending way too much time working and could see that the complexity of practicing medicine would continue to increase in the years ahead.

I began to look for ways to cope and came across an article in Family Practice Management by Peter Anderson, MD, and Marc D. Halley, MBA.1 The article described a new model in which a physician works simultaneously with two clinical assistants – a registered nurse (RN), a licensed practical nurse (LPN), or even a capable medical assistant (MA) – allowing them to assume more responsibility for each patient encounter so the physician can focus on the patient and medical decision-making. The additional nurse responsibilities include gathering an initial history (including the history of present illness, HPI; review of systems; past medical, social, and family history, PSFH; and health habits) and then staying in the exam room to document the physician encounter, order needed tests, print handouts, send prescriptions to the pharmacy, and complete the note including the assessment and plan. By shifting many of the ancillary physician tasks to well-trained clinical assistants, the physician can focus on what he or she is uniquely trained to do – provide high-quality acute, chronic, and preventive care in the context of a therapeutic relationship. After discussing this idea with my nurse (an LPN) and practice manager, we decided to try this new model.

My nurse and I started slowly, selecting several days where we would see fewer patients, thereby allowing additional time to learn our new process. It was a significant adjustment for both of us. She was now in charge of the documentation (and thus the computer), and it became necessary for me to clearly verbalize every aspect of the visit, including the physical exam, the assessment, and the plan for treatment or additional workup (labs, imaging, medications, referrals, etc.). We used Anderson and Halley's model as our starting point, but soon our process evolved based on our own skills and strengths, the needs of our patients, and the limitations of our office space, schedule, and electronic health record (EHR). After experimenting for a month, we were both convinced that we were ready to fully commit to this new model and decided to hire a second nurse. Because we had spent significant time fine-tuning our system, the training process for our second nurse (also an LPN) was relatively smooth, and my original nurse was able to do the bulk of the teaching.

Adjustments to the process

Every new process requires some experimentation and modification in the early stages, and for our practice key adjustments occurred in the following areas:

Communication with nurses. When we first began, I would handwrite my assessment and plan for each patient encounter to ensure accuracy. Quickly, my nurses let me know that this was a waste of time. Instead, they suggested that I clearly explain each diagnosis and associated plan to the patient, and they would capture the information as I spoke. The nurses have also demonstrated that they can capture patient instructions as we discuss them, and they now typically print those instructions at the conclusion of each visit. Today it is unusual for me to type or handwrite anything during an office visit.

Access to patient data. Each of our exam rooms has a desktop computer that we use to navigate the EHR. Lab and imaging results import electronically into the EHR, as do many of our consult notes. With my nurse in the room using the computer during the office visit, I lost the ability to peruse the chart during the visit, so I began to use an iPad with our wireless Internet connection to view a read-only version of the chart. The iPad also allows me to review the history related to each problem, the problem list, and current medications without pulling my nurse away from her documentation responsibilities.

Chart review. As we progressed with our new model, I continued to gradually shift more responsibility onto my nurses' capable shoulders. They assumed responsibility for immunization status (checking status for adults and children, administering needed vaccines, creating catchup schedules, etc.), preventive care, and even some basic chronic disease management (confirming annual diabetic eye exams and referring as needed, ordering annual lipid panels when appropriate, etc.). The nurses found that in opening a visit note, they were essentially doing a thorough chart review including reviewing, updating, and sorting the problem list; reviewing preventive care needs; sorting the medication list; reviewing and reorganizing the PFSH and health habits; starting the HPI by searching the chart for any prior tests or visits related to the chief complaint (as recorded by the front desk staff when scheduling the visit); and even starting the assessment and plan portion of the note by listing the relevant diagnoses. It was not possible to accurately complete such a chart review between patients, so my nurses agreed to arrive about an hour before our first patient each day to allow additional time for this work.

Patient check-in form. We have continually worked to implement processes that improve patient flow and efficiency during office visits. One of our more successful processes involves using a patient check-in form. Early on, it became apparent that the rooming process was a bottleneck in our patient flow because of the need to confirm problems, medications, allergies, social history, family history, habits, etc. I had asked my nurses to attempt to quickly update these at each office visit, and it turned into a time-consuming process, particularly for complex patients on multiple medications. To expedite the process, we worked with our EHR support staff to create a one-page document that lists a patient's medications, allergies, family history, social history, health habits/risk factors, pharmacy of choice, and advance directives. These forms are printed directly from the EHR during the morning chart review and are given to the front desk staff to pass out to patients when they arrive. This allows patients to review much of their history while sitting in the waiting room and allows the nurses to address only changes that need to be made. As an added benefit, patients appreciate that we put time into prepping for their arrival rather than handing them a blank form to complete.

Patient privacy. I was concerned that having a nurse present in the exam room might be a distraction for patients or make them uncomfortable sharing sensitive information. While we did receive several questions initially about the nurse being in the room, I have been pleasantly surprised by how many patients don't even seem to notice. There are occasional instances when it is evident that a patient would be more comfortable without a nurse present during the visit, and the nurses can usually ascertain this while rooming the patient. Overall, feedback has been amazingly positive. Rather than viewing the nurses as an intrusion, patients appreciate the additional resources that my nurses have become. They also seem to recognize that the nurses' presence allows me to be fully focused on them, rather than trying to manage charting, test orders, referrals, and refills while providing their care.

Space, workflow, and scheduling issues. Because my colleagues were not implementing the same practice model that I was, I was careful to limit the impact on them. To create a new workspace for my second nurse, I cleared some supplies from an unused desk, purchased a new computer, purchased a new office chair, and moved an unused phone. I typically have access to only two or three exam rooms while seeing patients (the Anderson and Halley model suggests three to five exam rooms), but I have not asked for more. I have found that even with two exam rooms I am considerably more efficient under this model.

While both of my nurses participate in patient visits throughout the day, they typically have short breaks between patients and can use this time to manage phone calls, medication refills, and other peripheral nursing issues. Because of this, we have not needed to schedule additional time for the nurses to manage these tasks, although we have utilized our group's two full-time triage nurses for support on our most hectic days.

The transition to our new model has probably been most difficult for our office manager and our group's lead nurse. A new process was required to schedule my nurses, and it can be tedious to manage schedules when I am out or one of my nurses is out. I have just recently started training some of our other office nurses in the new model, but previously I would have to resort to my old single-nurse system if one of my two nurses was out of the office.

Ongoing improvement. To fully implement this system requires nurses who are motivated and willing to assume more ownership over each patient encounter. The nurses' knowledge of each patient and their overall medical knowledge has grown as a result of their active participation in each visit, and they have learned by watching how I make decisions and conduct the medical workup. I also continue to teach them in a more formal manner by using interesting cases that we see, and I have learned this model requires an ongoing commitment to training. I started out meeting with my nurses for one hour each week, and even though I have been using this system for almost two years, I continue to meet with them at least twice per month. During these meetings I elicit feedback about problems or inefficiencies, provide feedback on recent chart notes, and provide teaching about changing medical standards of care. My nurses are now often the ones to identify problems and suggest appropriate changes to improve our model and the care we provide. These routine meetings have created a culture of teamwork and a continual focus on innovation – traits that will likely serve us well in the ever-changing world of medicine.

How the model is working

Two years into the model, we can report positive results.

Patient care statistics. The organization I work for monitors patient care data, generating physician report cards for preventive care and chronic disease management. Since implementing this new practice model, I have seen an improvement in most of my report card measures, particularly those that rely more on my nurses to complete. For example, the table below shows improvements in virtually every category of diabetes care, with a particularly large jump in the percentage of diabetes patients who have received foot exams, a task I have completely turned over to my nurses.

IMPROVEMENTS IN CARE

Since implementing my new practice model, in which nurses take greater responsibility for certain aspects of the patient visit, I have seen improvements in most of my report card measures, including those for diabetes care, shown here.

| Percentage of diabetes patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes measures | Goal | Old system | New system |

| A1C > 9% | < 15% | 5% | 0% |

| A1C < 7% | > 40% | 53% | 64% |

| Blood pressure > 140/90 mm Hg | < 35% | 22% | 7% |

| Blood pressure < 130/80 mm Hg | > 25% | 53% | 64% |

| Eye examination completed | > 60% | 47% | 48% |

| Smoking status and cessation advice or treatment provided | > 80% | 98% | 98% |

| LDL > than 130 mg/dl | < 37% | 15% | 9% |

| LDL < 100 mg/dl | > 36% | 58% | 62% |

| Nephropathy assessment completed | > 80% | 95% | 95% |

| Foot examination completed | > 80% | 60% | 79% |

Finances and productivity. The costs incurred with this new model can be divided into two categories: initial startup costs and ongoing costs. I estimate that my initial startup costs were in the range of $15,000. This includes the fairly nominal cost of additional office equipment (computer, office chair, etc.) and the more significant cost of slowing down my days as I brought both nurses up to speed on the new system. The only significant ongoing cost is paying the salary and benefits of my second LPN, approximately $8,000 per quarter. This is less than you might expect because four months after transitioning to this new model, I made a personal decision to decrease my full-time equivalent (FTE) status from 1.0 to 0.75. Thus, I am not responsible for the full salary of my second nurse. The remainder of her time is allocated to other parts of the practice.

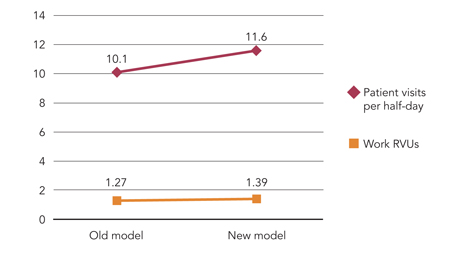

My FTE change makes it nearly impossible to calculate how my practice change has affected revenue, but I can say that my office productivity has increased. We measure productivity in terms of patient visits per half-day and average charge per patient visit, which we track based on work relative value units (RVUs). Since moving to this new system, I have seen my patient visits per half-day increase by 15 percent and my average charge (work RVU) per office visit increase by 10 percent (see the graph below). Because some of our practice costs are divided based on productivity, this increase in my productivity has led to a relatively minor, but ongoing, increase in those costs.

IMPROVEMENTS IN PRODUCTIVITY

Under my new practice model, patient visits per half-day have increased 15 percent and work relative value units (RVUs) have increased 10 percent. These numbers reflect an eight-month average before and after changing to the new model.

Although this new model has certainly brought an increase in expenses, I have seen a much greater increase in productivity and revenue, which has allowed me to maintain an annual income above the national median of $160,000 for a full-time family physician, despite having decreased my FTE status to 0.75.

Nurse and patient satisfaction. During this transition I have regularly asked my nurses for feedback regarding their satisfaction with our change, and when there have been frustrations or difficulties, I have done my best to work creatively with them to correct those. At this point, I am happy to report that my nurses are both very pleased with our current system. My original nurse reports that “Overall, I am very happy with the two nurse system. My favorite thing about it would be that I get to see from start to finish the entire diagnostic and treatment process. It allows me to become educated on each patient's history and treatment plan, which in turn allows me to provide appropriate care and to be a better advocate for that patient. While working so closely together, I've been able to gain an understanding of how Dr. Anderson practices, and I have become more confident in myself and my own skills. Our care as a team has become significantly more thorough, and we are able to focus now on providing comprehensive care to each individual.”

Although we have not conducted a formal patient survey, the feedback we have received from patients has been almost universally positive. Patients are happy to have my undivided attention while in the exam room, they appreciate getting so much done with each office visit, and they are grateful that my increased efficiency has allowed me to be more available for same-day appointments.

Empowered to change our work

This journey in restructuring my practice model has led me to a place where I am able to focus more on my patients, provide higher quality care, be more productive, and have happier employees. As physicians, we should not view ourselves as beholden to old models of care. Instead, we ought to view ourselves as empowered to institute fundamental changes to our work. The practice of family medicine is likely to get more demanding in the years ahead, and it is our opportunity and responsibility to build innovative practices that meet these demands while enabling excellent patient care, employee satisfaction, and a sustainable and meaningful personal life.