When discussing a patient's risk of developing a disease or the risks associated with a screening test, these simple techniques can ensure clarity.

Fam Pract Manag. 2018;25(6):28-31

Author disclosure: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

Effective communication is a hallmark of patient-centered primary care, but communicating with patients about risk can be complicated. Patients' risk of developing a certain disease, their risk reduction from taking a certain medication, or the risks and benefits of a certain screening or procedure are not easy to understand. Nevertheless, risk conversations are crucial to helping patients make informed decisions that align with their personal values and perspectives. We call this shared decision making.1

People's perception of risk can be affected greatly by the way their physician communicates about risk as well as a number of other factors. Data have shown that clinicians tend to overestimate the risk of a condition and underestimate the risk of complications and side effects.2 Additionally, emotion can affect patients' understanding of potential risks.3 For example, hearing a risk estimate of a 1 in 27 chance of developing bladder cancer will naturally feel scarier than the same risk estimate for a rash. People also have strong emotions if they have had a personal experience with a condition and may interpret the data differently based on that experience. For example, if a patient's neighbor had an infection after a hip replacement and needed to be re-admitted for IV antibiotics, that patient may not believe a surgeon who later says the patient's risk of infection is low. Patients' understanding of risk can also be affected by numeracy, that is, their ability to understand numbers or percentages. There is evidence that numeracy may be a strong predictor of a patient's decision-making skills.4 Patients with low numeracy may have difficulty understanding the risk of side effects or the benefits versus risks of screening tests, and they may be less likely to ask questions about treatment or screening decisions. Low numeracy is indirectly related to health outcomes.5

Numeracy screening questions may be helpful in certain situations (see “Two questions to assess patient numeracy”); however, routine numeracy screening of all patients is not practical or recommended. Instead, physicians should take universal precautions to provide understandable and accessible information to all patients, regardless of their numeracy or health literacy levels.

KEY POINTS

Remind patients that all options confer some risk.

Using absolute risk can help you avoid bias because relative risk tends to make changes in risk appear larger.

How you present numbers, whether you use visual aids, and the language you use can all affect a patient's ability to understand risk.

TWO QUESTIONS TO ASSESS PATIENT NUMERACY

Routine screening of patient numeracy is not feasible; however, the following questions may be helpful in certain situations, for example, if a risk conversation is not moving forward due to a lack of understanding.

1. Which of the following indicates the greatest risk of getting a disease?

A. 1 in 10.

B. 1 in 100.

C. 1 in 1000.

2. Which of the following is bigger?

A. A 1/3 pound burger.

B. A 1/4 pound burger.

1. Cokely E, Ghazal S, Garcia-Retamero R. Measuring numeracy. In: Anderson B, Schulkin J (eds). Numerical Reasoning in Judgments and Decision Making About Health. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014:11–38.

1. REMIND THE PATIENT THAT ALL OPTIONS CONFER SOME RISK

“Medicine is a science of uncertainty and an art of probability,” in the words of Sir William Osler.6 Living with uncertainty is a constant fact of life for both physicians and patients. All options confer some risk; they have potential positive and negative outcomes, and the probability of those outcomes is never zero or 100 percent, which would provide certainty. The uncertainty is what makes the communication of risk difficult. However, the ideas of risk and uncertainty are common in our culture. For example, driving a car comes with the risk of a car accident, and that risk increases or decreases based on certain behaviors. However, because we can never be certain whether we will get into a car accident, we buy auto insurance. We do what we can to reduce the risks of bad outcomes to reasonable levels and go ahead with our lives.

One strategy you can use in communicating uncertainty to patients is to help them understand the difference between probability and possibility. Some outcomes may be possible but not probable. For instance, if you calculate the 10-year risk of breast cancer for a 47-year-old woman with no risk factors, you will find that her risk is about 1.3 percent. Is it possible that she will develop breast cancer? Yes. Is it probable? No. Risk predicts both probability and possibility.

2. USE ABSOLUTE RISK RATHER THAN RELATIVE RISK TO REDUCE BIAS

A Cochrane review of 35 papers found that participants (both patients and health professionals) understood absolute risk reduction and relative risk reduction about equally, but relative risk reduction was more persuasive.7 Research has shown that changes in risk appear larger when presented using relative risk versus absolute risk.8 And a more recent systematic review demonstrated that data presentations that included absolute risks maximized accuracy without influencing decisions to accept therapy.9

Based on these findings, because the same information can be communicated either way, using absolute risk is important if you do not want to unduly influence the patient's decision. So, instead of saying “This medication will reduce your risk of X by 50 percent” (relative risk reduction), you could say, “This medication will decrease your risk of X from 6 in 1,000 to 3 in 1,000” (absolute risk reduction).

3. BE CAREFUL ABOUT THE WAY YOU PRESENT NUMBERS

When discussing the risk that an event will occur, you have several options:

Percentages (40 percent risk),

Fractions (2/5),

Simple frequencies (2 in 5).

People understand these numbers differently, so explaining risk in several different ways may be helpful.10 Some data suggest that patients understand simple frequencies better than percentages.7 When using simple frequencies, using comparable numbers will improve understanding. For example, comparing 3 in 200 with 3 in 25 can be confusing to patients, so instead compare 3 in 200 with 24 in 200. Using frequencies with the smallest numbers possible (but not “1 in X”) can also improve understanding. For example, instead of saying 25 in 1,000, say 5 in 200.

Studies have shown that patients overestimate risk when it is presented in a “1 in X” format.11 The hypothesis is that this gives too much attention to the “one,” and patients over-identify with the single person.

Consider the following exchange:

Clinician: “The risk is small, one in 300.”

Patient: “Yes, but I am always that one.” Now consider the alternative:

Clinician: “The risk is small, 3 in 1,000.”

Patient: “Yes, that does sound small.”

These same principles apply to fractions as well. Using the same denominator and the smallest denominator will help improve understanding.

One of the downsides of using percentages is that, when the risk is less than 1 (i.e., 0.3 percent), it may be difficult for patients to understand. In these instances, it is better to use a frequency (3 in 1,000).

4. USE VISUAL AIDS

People learn in different ways. For some people, particularly those with low literacy, hearing the numbers is less clear than seeing a visual example of the same numeric information.

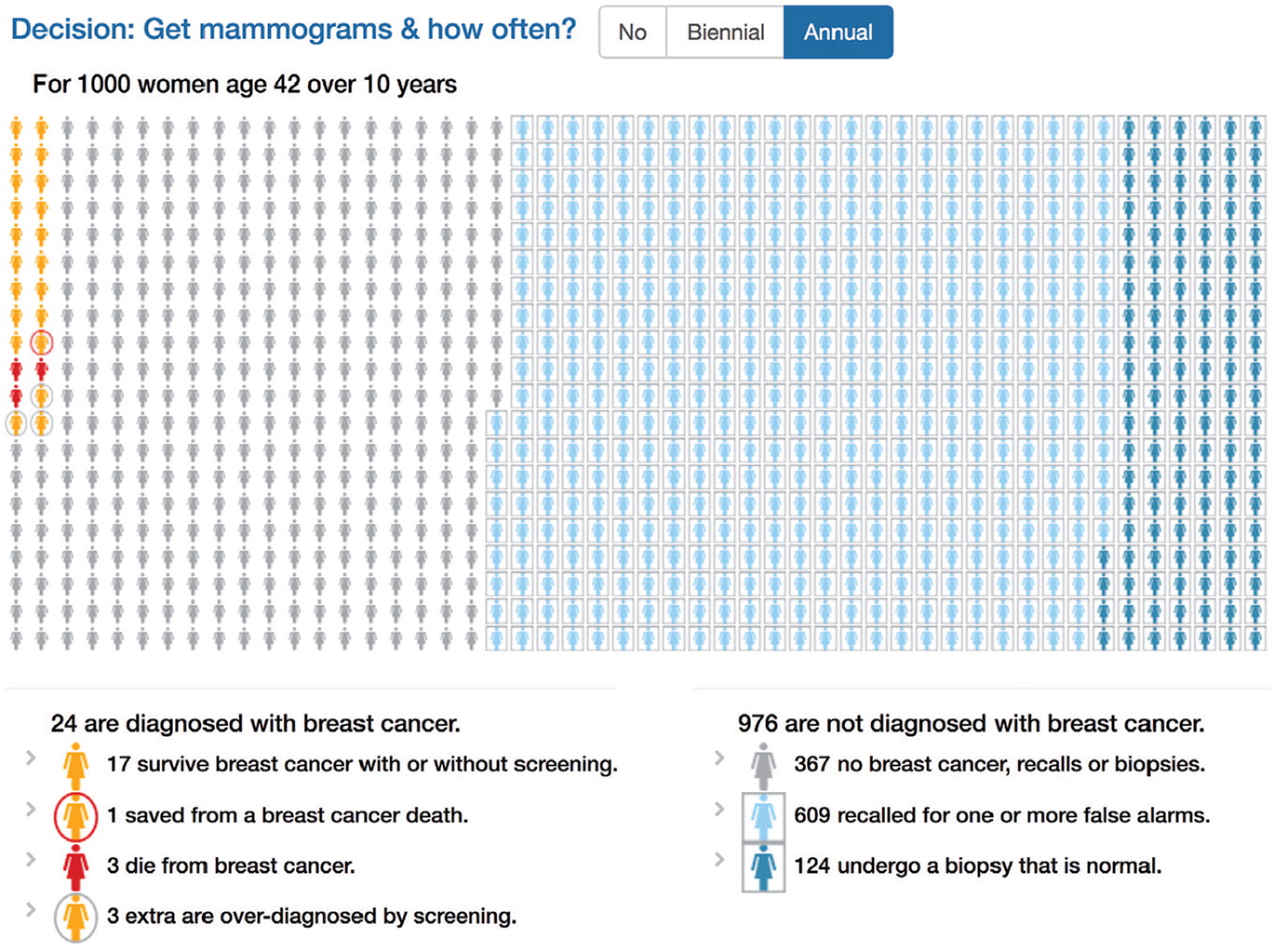

Visual aids are excellent methods of communicating possible outcomes.9 A Cochrane review found that use of patient decision aids increased knowledge, helped patients clarify their values, and may improve value-concordant decisions.12 Using pictographs is an especially effective method to convey risk information and can help patients make unbiased decisions.8,13,14 (See “A sample pictograph.”) Other helpful visual methods to convey risk are bar graphs or pie charts.10 (See “Online decision aids” to access helpful visual aids or the information needed to build your own.)

A SAMPLE PICTOGRAPH

The following pictograph, generated by HealthDecision, a clinical decision support website, depicts a patient's risk of breast cancer as well as the risks associated with screening mammograms.

ONLINE DECISION AIDS

The following resources can provide visual aids and data to help explain risks.

5. USE PLAIN LANGUAGE

People are more likely to understand your explanations if you use clear, plain language.8 This means avoiding the use of technical terms (e.g., say “normal test result” rather than “negative test result”), using neutral and active language (e.g., say “ if you get this test” rather than “if one would get this test”), and avoiding the use of descriptive language only (e.g., “low risk” or “high risk”). Descriptive language reflects the speaker's perspective, and the patient will often have a different interpretation.15 Research has shown that using patient narratives, such as stories about prior patients' experiences with certain interventions, can also create bias and unduly influence decision making.10

GETTING STARTED

Easier access to evidence-based information has given physicians improved tools for risk communication. These tools include point-of-care resources, such as Up to Date and Epocrates, as well as online resources such as the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force website and the Cochrane Reviews website.

But having access to evidence-based information about risk is not enough. You must also make sure patients understand it. Using the five strategies described in this article will help you communicate risk in a manner that is unbiased and easier to understand, thereby helping patients make more informed decisions.