If addressing patients' social needs sounds overwhelming, the results of this pilot project might surprise you.

Fam Pract Manag. 2019;26(5):13-19

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

“Social determinants of health” (SDOH) has become an inescapable buzzword in family medicine in part because of the magnitude of impact that SDOH have on our patients' wellbeing. Drawing a direct comparison between social factors and medical conditions, researchers have estimated that low education, racial segregation, and low social support make a contribution to mortality that is equivalent to acute myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, and lung cancer, respectively.1 Particularly as we strive toward the Quadruple Aim in health care, the “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age”2 can no longer be categorized strictly as nonmedical factors and, therefore, outside the scope of primary care.

Although many in primary care agree about the importance of screening patients for social needs and referring to supportive community resources, legitimate concerns exist about the feasibility of doing so. To explore these issues, our family medicine clinic recently conducted a nine-month SDOH pilot project. This article shares our outcomes and some surprising lessons learned.

KEY POINTS

Social factors such as low education, racial segregation, and low social support can have an effect on mortality that is similar to medical conditions such as acute myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular disease, and lung cancer.

In the authors' pilot study, 58 percent of clinicians began the project thinking they were too busy for social determinants of health (SDOH) screening, but only 21 percent felt that way by the end of the project.

Numerous SDOH screening tools exist, so practices can simply adapt one for their own use based on the social needs most common in their patient population.

REASONS TO CONSIDER SDOH SCREENING NOW

A variety of forces make this a promising time to integrate SDOH screening into routine medical practice. An early but growing body of evidence provides guidance on how to implement this practice in various settings.3–5 A number of tool-kits exist to support SDOH screening in clinical settings, including those from the American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, and the National Association of Community Health Centers. Previous initiatives have demonstrated that screening for social needs in medical settings is acceptable to patients6 and can result in better access to community resources and resolution of social needs.7,8 Although studies measuring the effect of SDOH screening on health outcomes are limited, some investigators have found benefits related to anxiety,9 blood pressure, and low-density lipoprotein.10

SDOH screening is becoming more financially feasible as alternative payment models such as shared savings programs and global capitation provide a revenue stream to support additional staff such as social workers, care coordinators, and patient navigators.11 Both public and private payers have demonstrated a willingness to invest in social interventions. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield has developed initiatives that pay for patient transportation and food delivery, and UPMC for You, a Medicaid managed-care organization in Pennsylvania, launched a program to provide permanent housing for eligible members.12

This rich environment, coupled with a desire to attend broadly to wellbeing and equity among our patients, motivated our family medicine clinic to pursue its own initiative to screen patients for social needs and refer to supportive community resources.

HOW WE GOT STARTED

This SDOH screening project was conducted at AF Williams Family Medicine Center, an academic clinical setting made up of 45 family medicine faculty and residents associated with the University of Colorado School of Medicine. AF Williams has more than 18,000 patients empaneled and conducts almost 40,000 visits annually with nine physicians or other providers per clinic session.

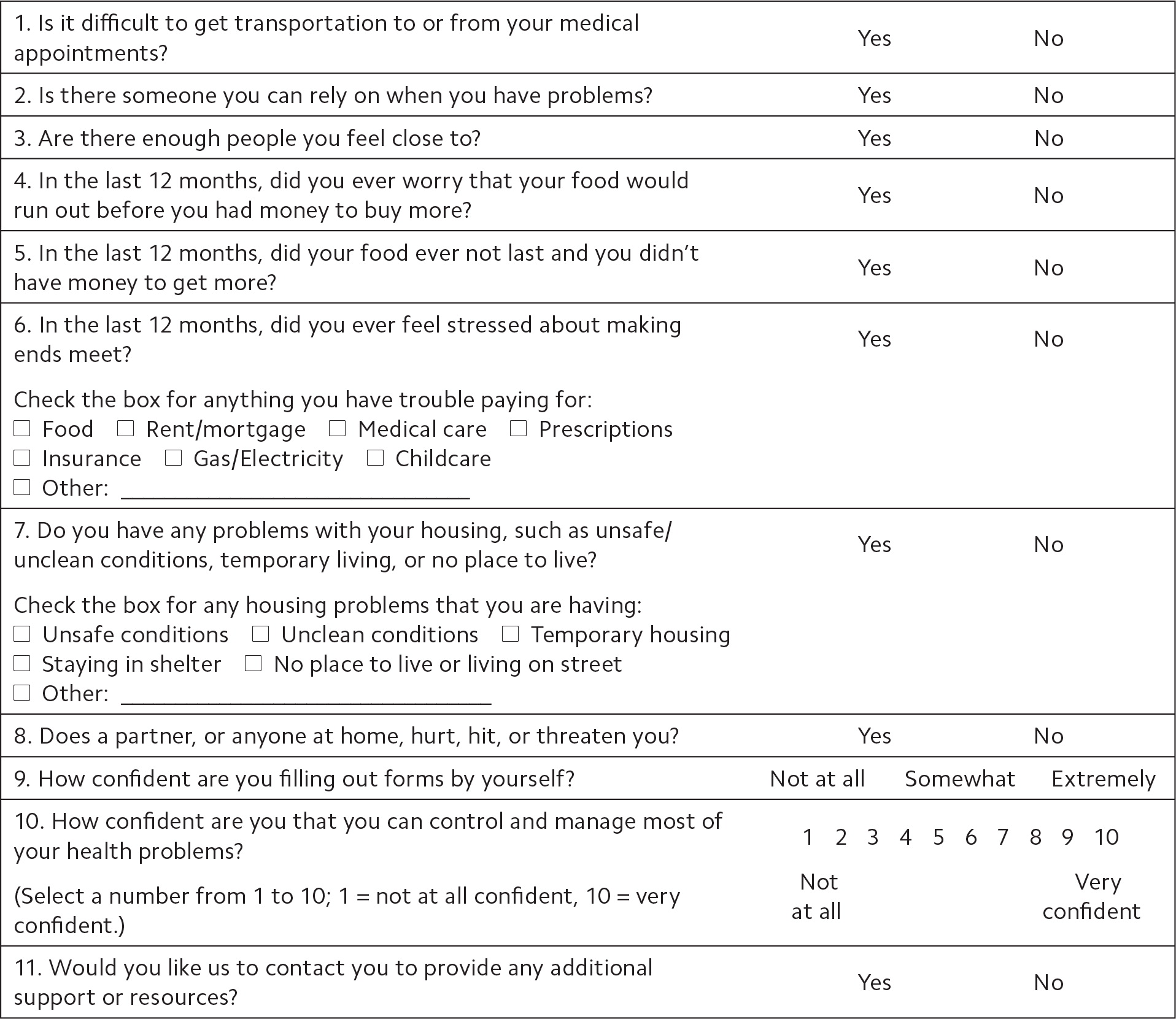

Screening tool. The screening tool we developed was the result of reviewing multiple existing screening tools13–19 and discussing their merits among the clinic's SDOH screening workgroup. We wanted to provide patients with a streamlined, one-page screener that included needs we could act on with our current clinic staff if patients screened positive and requested clinic support. We focused on lack of transportation, social isolation, food insecurity, financial strain, housing problems, and household violence. The screening tool included two additional questions on health literacy and self-efficacy to help us better understand our patient population, and it asked patients whether they would like our assistance to address their social needs.

SOCIAL NEEDS: PATIENT QUESTIONNAIRE

Health starts where we work, play, learn, eat, and sleep. Problems in any of these areas can affect your health. We may be able to provide assistance, so we hope you will answer the following questions. You do not have to answer any questions you do not want to. Anything you write will be kept confidential in your medical record.

PLEASE CIRCLE YOUR ANSWERS.

FPM Toolbox: To find more practice resources, visit https://www.aafp.org/fpm/toolbox. Developed by the University of Colorado AF Williams Family Medicine Center. Copyright © 2019 American Academy of Family Physicians. Physicians may duplicate or adapt for use in their own practices; all other rights reserved.

Workflow. We give patients our SDOH screening tool at the check-in desk if their visit is an establish-care appointment, annual wellness visit, well-child care, or new obstetric intake. Patients complete the paper screener in the waiting room and hand it to the medical assistant (MA) during the rooming process. The MA manually enters the screening results into an electronic health record (EHR) flowsheet. If the patient has any “positive” responses and indicates a desire to be contacted for assistance, the MA makes an internal referral to the clinic social worker specifying which screening question was positive. When available, the social worker may see the patient during the clinic visit. Once the rooming is complete, the MA provides a warm hand-off to the physician or other provider indicating whether any screening questions were positive and whether the patient requested clinic assistance. The SDOH screening tool is also available in the exam room and can be administered at any time if needed.

Workgroup. An SDOH screening work-group, which included physicians, other clinicians, nurses, medical assistants, front-desk staff, a practice coach, and a social worker, met monthly to develop our screener and clinic workflows. Once the screening pilot began, the group tracked our screening rates and frequency of positive screens. It also developed methods to improve screening rates, which included disseminating clinician-level data showing the frequency of screening eligible patients, placing the screening tool in multiple locations in clinic, and using multiple communication strategies such as email, meetings, and daily huddles.

Community relationships. The work-group developed several partnerships with community organizations to help support the needs of our patients. For example, we established an electronic referral system between our family medicine clinic and the nonprofit organization Hunger Free Colorado. After receiving a patient referral, the organization calls the patient to provide information on emergency food resources and enrolls the patient in our state's Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, if eligible. Hunger Free Colorado also sends us monthly reports summarizing the services our patients have received.

WHAT WE FOUND

During the nine-month pilot, we screened 2,018 patients out of 5,038 eligible patients (40 percent).

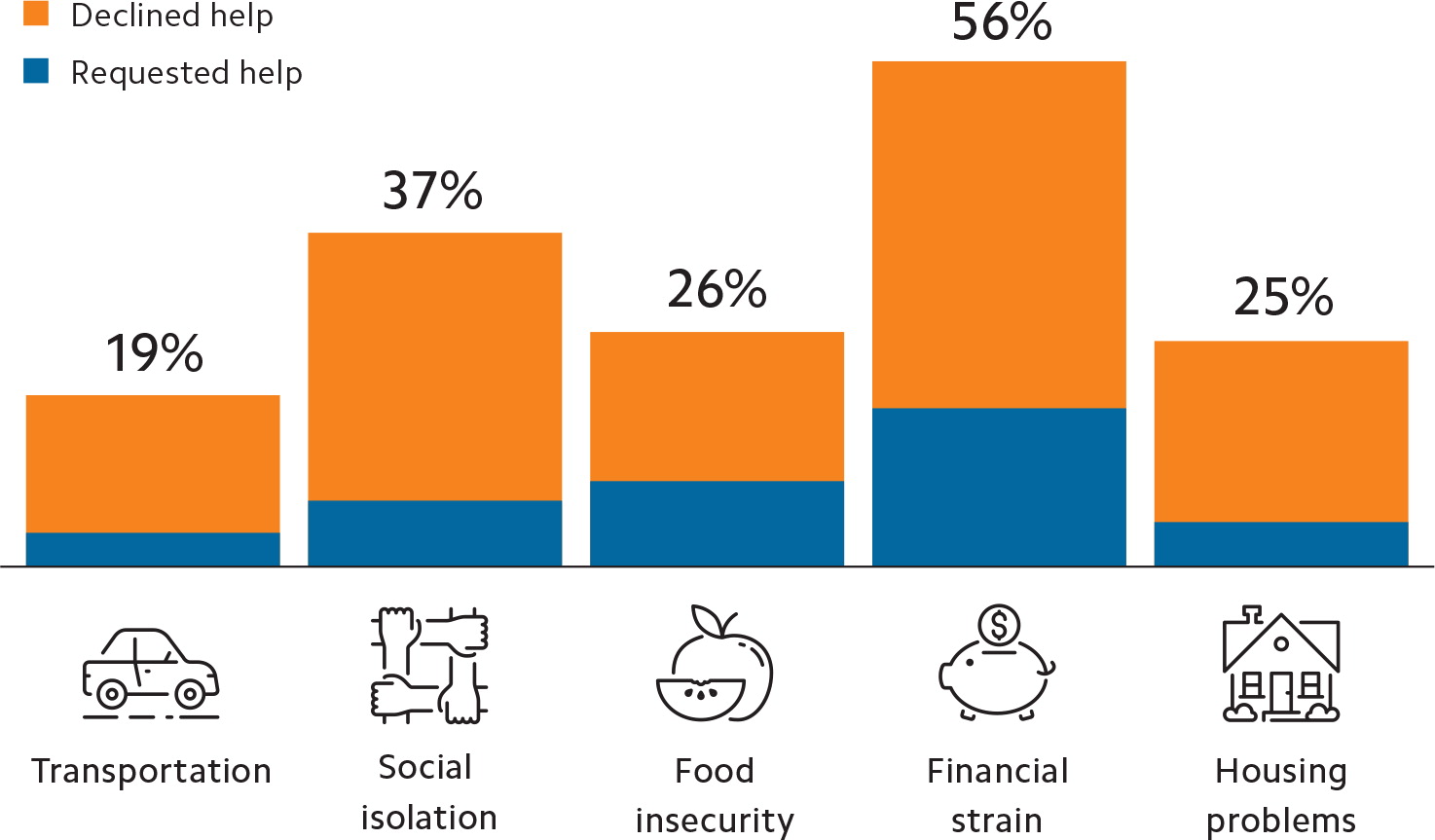

Number of positive screenings and requests for support. Of those patients screened for SDOH, 541 (27 percent) reported at least one need. The most commonly reported needs were financial strain and social isolation. (See “Common social needs among patients screened.”) Of those patients who disclosed at least one need, only 124 (23 percent) requested support from the clinic team. Depending on the type of need, rates of those requesting assistance ranged from 21 percent to 38 percent.

Insurance, ethnicity, and race. The screening process undersampled patients with public insurance. Among the screened population, 83 percent had commercial insurance, 7 percent had Medicare, 6 percent had Medicaid, and 4 percent had another plan; among those eligible for screening, 76 percent had commercial insurance, 10 percent had Medicare, 9 percent had Medicaid, and 4 percent had another plan.

We found no differences in ethnicity between screened and eligible patients, but we did find differences in race. The screening process undersampled African Americans (11 percent of the screened population vs. 13 percent of those eligible for screening) and oversampled Caucasians (62 percent of the screened population vs. 60 percent of those eligible for screening).

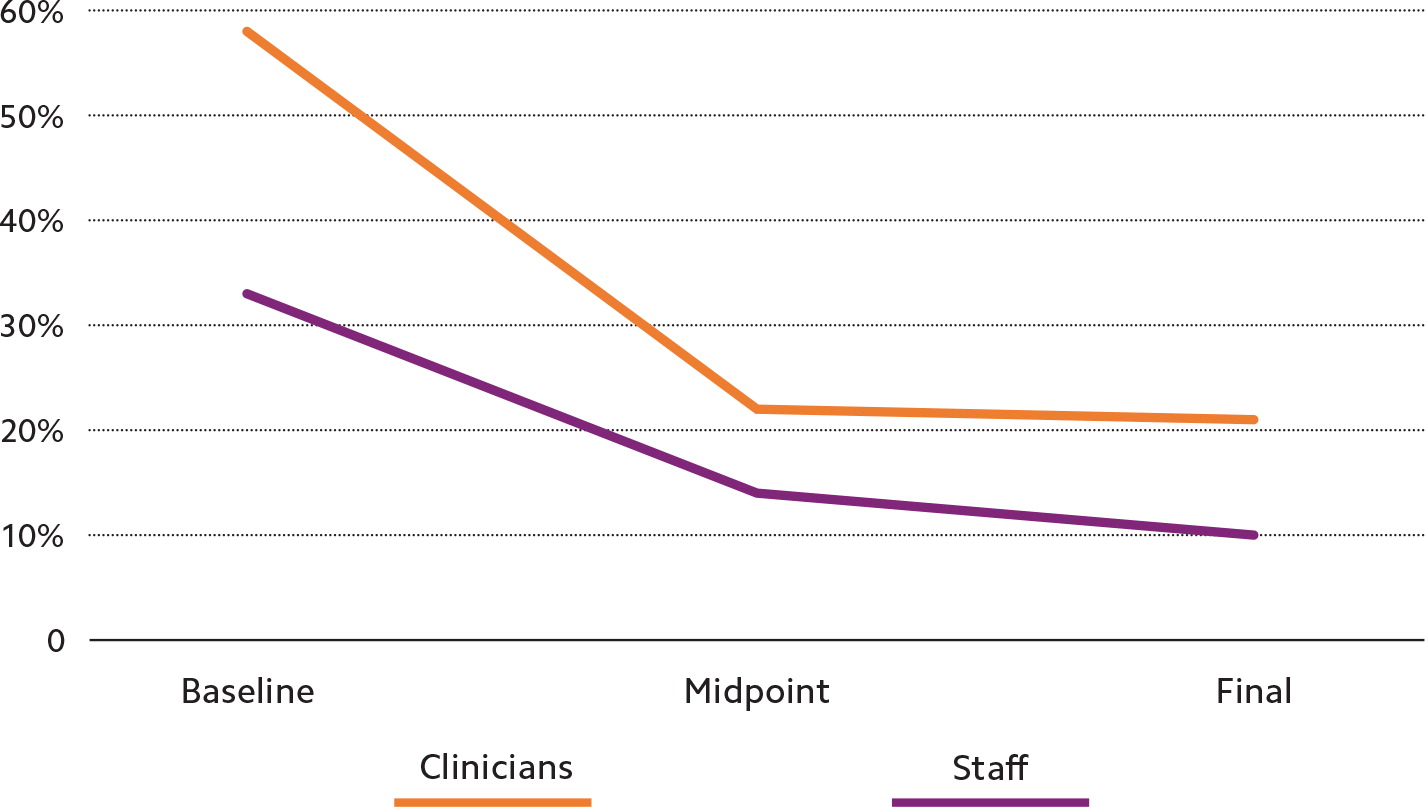

Clinician and staff attitudes. To understand how our clinicians and staff felt about this new responsibility, we conducted online surveys prior to the launch of the screening pilot, five months later, and at the conclusion of the pilot. On the final survey, key results were as follows:

91 percent of staff and 92 percent of clinicians agreed that the screening benefitted patients,

91 percent of staff and 96 percent of clinicians felt that we should continue using the social needs screening questionnaire despite the additional work,

100 percent of respondents agreed it is a primary care clinic's responsibility to help patients with their social needs,

10 percent of staff and 21 percent of clinicians felt that the clinic was “too busy” to deal with patients' social needs; at baseline, 33 percent of staff and 58 percent of clinicians felt that the clinic was “too busy” to deal with patients' social needs (see “Clinician and staff attitudes on SDOH screening”).

SEVEN LESSONS LEARNED

Our nine-month pilot project to implement SDOH screening in primary care taught us several key lessons:

1. Screening doesn't have to be overwhelming. Although 58 percent of our clinicians went into this project thinking they were too busy for SDOH screening, only 21 percent felt that way by the end of the project. We found that screening rates and clinic engagement increased dramatically when we began practice-wide data sharing that demonstrated how many patients were screened (40 percent of eligible patients), how many patients reported social needs (27 percent of those screened), and how many patients requested assistance from clinic staff (only 23 percent of patients who reported a need). In the end, the work was not overwhelming, as some had feared it would be.

2. Don't start until your clinic is ready. We have developed a checklist to help determine clinic readiness for SDOH screening and identify implementation strategies. The first item on the checklist is for practices to explore their local SDOH landscape before jumping into screening so they can sidestep avoidable struggles. This includes identifying which social needs are most prevalent in your practice by consulting existing community health assessments from local public health agencies or nonprofit hospitals, and asking your clinic social workers or other staff who are already discussing social issues with patients to share their insights. If enthusiasm and resources permit, you can also conduct a brief waiting room survey to solicit patient input and help focus your clinic's attention on the most important needs in your population.

CHECKLIST FOR CLINIC READINESS TO IMPLEMENT SDOH SCREENING

3. Connections are key. The success of screening rests on the strength of the team, those doing the work and those overseeing the work, both inside and outside the clinic walls. Our screening workgroup included representation from all groups who would participate in the screening process, allowing us to anticipate and quickly respond to issues that arose along the way. Involving or at least gathering input from patients and system-level leadership can further inform the strategy. An enthusiastic physician champion helped build awareness and urgency around the issue of our patients' social needs and kept the process moving forward. In other settings, this champion could be any clinician or staff member who cares deeply about this issue and is willing to bring others along on the journey.

You must also build connections with community organizations and service providers so that you can act on the needs your patients disclose. Creating a resource directory is the first step, and its scope will depend on your clinic's capacity. These community partnerships can range in complexity from a simplified referral process to something more ambitious such as co-located services.

Health sciences students can be valuable connections as well. Their skills, time, and academic requirements can support your SDOH efforts such as conducting waiting room surveys, developing a list of community resources, and collecting data.

4. You don't have to reinvent the wheel. Once you identify the greatest social concerns among your patients and the availability of community resources, you can develop your screening tool, but you don't have to start from scratch. Review existing questionnaires, such as those mentioned earlier in the article, and see if you can adopt or adapt an available tool. The University of California-San Francisco's Social Interventions Research & Evaluation Network has an online Screening Tools Comparison that allows for easy evaluation of several commonly used questionnaires.

You can also reach out to nearby clinics who are already doing SDOH screening to see if they have screening tools, community partnerships, or workflows you can learn from or replicate.

5. Everyone needs to understand the workflow. Your SDOH workflow should address the following questions: Which patients will be screened and during what part of the clinic encounter? Who is responsible for administering the screening questionnaire, and who is responsible for acting on results? Will the questionnaire be administered on paper or verbally? How will results be documented? And how will you integrate data collection that is meaningful to your practice? Map out the process visually with participation from all types of clinic personnel in order to pinpoint key decision areas and find potential problem areas before implementation.

6. It's OK to start small. If capacity or overall clinic support is low, it may be best to start with one or two screening questions. An initial, smaller success can provide lessons learned, data demonstrating the importance of screening, and patient stories to fuel maintenance or expansion of an SDOH screening program. Our pilot was preceded by a short-term trial of screening only for food insecurity. This effort helped to build clinic culture and confidence around tackling a wider array of social determinants.

7. Look beyond the launch. When laying the groundwork for SDOH screening, consider how the process will be sustained over time. This will require plans for initial and ongoing training for staff, physicians, and other providers, and a communication strategy that conveys the purpose of this new screening and cultivates a culture where the interconnection of social and physical wellbeing is embraced as a part of primary care. A system for ongoing evaluation of the screening process, including recognition and management of barriers, will also help keep the screening process healthy amid the changes that are bound to arise in any busy family medicine practice.