Evidence suggests that documentation support provided by scribes can help relieve physician burnout and increase practice productivity.

Fam Pract Manag. 2020;27(6):17-22

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

Although electronic health records (EHRs) were originally hailed as a means to improve clinical productivity, quality of care, and patient outcomes, the widespread use of EHRs has had the unintended effect of dramatically increasing the administrative burden on physicians. In fact, primary care physicians spend about half of their workdays on the computer during and after clinics.1 According to some estimates, every hour of direct patient care requires two hours of EHR work, and many physicians spend one to two hours a night on charting.1,2 Additionally, physician burnout rates in family medicine are well above 50%, and many physicians indicate that complicated EHR systems are a strong contributor to burnout.1,3

For physicians who are frustrated by cumbersome EHR systems and increasing documentation requirements, documentation support is one possible solution. Models of documentation support include the following:

Speech recognition software, which converts spoken notes to digital text saved in the EHR system. Emerging technology includes software that “listens” to the physician-patient interaction in the exam room and adds notes to the EHR automatically.

Scribes, which the Joint Commission defines as an unlicensed, certified, or licensed individual who enters information into the EHR or chart at the direction of a physician or licensed independent practitioner.4 Scribe services may be virtual — the documenter is not physically present for the physician-patient interaction and documentation is completed either in real time or after the visit — or in person. In-person scribe services typically are provided by care team members such as medical assistants (MA), advanced practice providers (APP), technicians, or medical scribes provided by an outsourced vendor.

This article reviews some of the available evidence on the effectiveness of in-person scribes and presents the outcomes of two different scribing models. While our focus in this discussion is primarily on in-person scribing services, we also provide a brief review of virtual services, given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the clinic environment.

KEY POINTS

Complicated EHR systems and time spent in front of the computer contribute to physician burnout. Scribes can help relieve the administrative burden.

The two primary implementation models for integrating scribes into a practice are in-house development and utilization of an outsourced vendor.

Both models of implementation for in-person scribes result in increased patient volume and physician and provider satisfaction.

SUMMARY OF EVIDENCE ON THE BENEFITS OF SCRIBES

The literature on scribes shows improvement in some metrics and no change in others.

In one study of a combined family and internal medicine clinic, the implementation of in-person scribes was associated with an increase in productivity. The clinic experienced a 10.5% increase in work relative value units (RVUs) and an 8.8% increase in patients seen per hour.5 In addition, after the implementation of scribes, the time physicians spent facing patients increased by 57% and time spent facing the computer decreased by 27%.5 However, the proportion of the clinic's charts still open at the end of the day did not change significantly compared to the prescribe period.5

In another study, scribes were found to improve all aspects of physician satisfaction, including time spent charting, time spent with patients, and chart quality and accuracy.6 In addition, the use of scribes improved the amount of time it took to close charts; 32.6% of charts drafted by scribes were closed at 48 hours, while 28.5% of charts drafted by physicians were closed at 48 hours.6

From a patient perspective, scribes do not appear to significantly change the patient experience. Patients appear to be comfortable with the presence of a scribe in the exam room5 and report high levels of satisfaction with their care, regardless of whether a scribe is present in the exam room or not.6–8

In a study investigating how scribes affect physician attitude and behavior, most negative provider comments revolved around clinic operational inefficiencies (e.g., workflows and administrative tasks), and not with the scribing support itself.9 Physician satisfaction increased when scribe support went beyond documentation to also include assisting with clinical procedures, paperwork, and writing letters.9

IMPLEMENTATION MODELS

There are two primary implementation models for integrating scribes into a practice: in-house development and utilization of an outsourced vendor.

For in-house implementation, the practice may choose to hire and train a scribe based on the specific needs of the practice, or expand the roles of existing staff (such as MAs, licensed practical nurses, or technicians) to also include documentation support. Expanding the MA role and scope to include health information technology and documentation involves evaluating and revising the internal medical assistant training program and managing any administrative issues that arise during the transition. MAs in this expanded role can, similar to a scribe, assist in collection of history of present illness (HPI), review of symptoms (ROS), and documentation of the physical exam. (Note: Under the E/M documentation changes that go into effect in January 2021, the HPI and ROS requirements for code selection are going away; see the related article.) MAs can also carry out post-exam orders, schedule follow-up appointments, assist with procedures, and review post-care instructions. As such, expanding the MA role offers continuity of care throughout the patient's visit.

Outsourced vendors typically provide a classroom or online training program for their scribes, followed by on-site supervision and training during onboarding. These vendors also usually manage any administrative tasks related to hiring, coordinating schedules with individual physicians, maintaining compliance with the customer's human resource requirements (e.g., immunizations and HIPAA), quality assurance, and various other administrative tasks.

Some outsourced vendors also offer virtual or remote scribes, who are not physically present in the room during the patient visit. Instead, virtual scribes are connected to the practice via a HIPAA-compliant transmitting or recording device, such as a laptop, tablet, microphone, or face-mounted technology, mostly in real time. The scribes may be in call centers or homes, domestic or international. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many scribe vendors have transitioned in-person scribes to virtual scribes. While there are fewer studies on virtual scribes, it appears that patients generally tend to accept their use, especially when the patient has a high level of trust in the physician.10

As the authors of this article, our focus and experience is on in-person scribe support. As such, we've included below the implementation stories of two separate institutions — one that implemented an outsourced vendor scribe program and another that used in-house development to expand the MA role to include scribing.

CASE STUDY: OUTSOURCED VENDOR SCRIBES

The Department of Family Medicine at the University of Michigan Health System (now called Michigan Medicine) in 2014 conducted a six-week pilot program evaluating scribes' impact on RVUs and number of patient visits. With the lessons learned from the pilot, the department subsequently and progressively rolled out changes across the system.

The University of Michigan opted for an outsourced vendor scribe program because it allowed the institution to explore the benefits of using scribes without the long-term cost of hiring permanent employees to fill this role. As part of the implementation, the department surveyed the physicians using scribes and collected data on patient satisfaction and financial outcomes associated with scribe use.

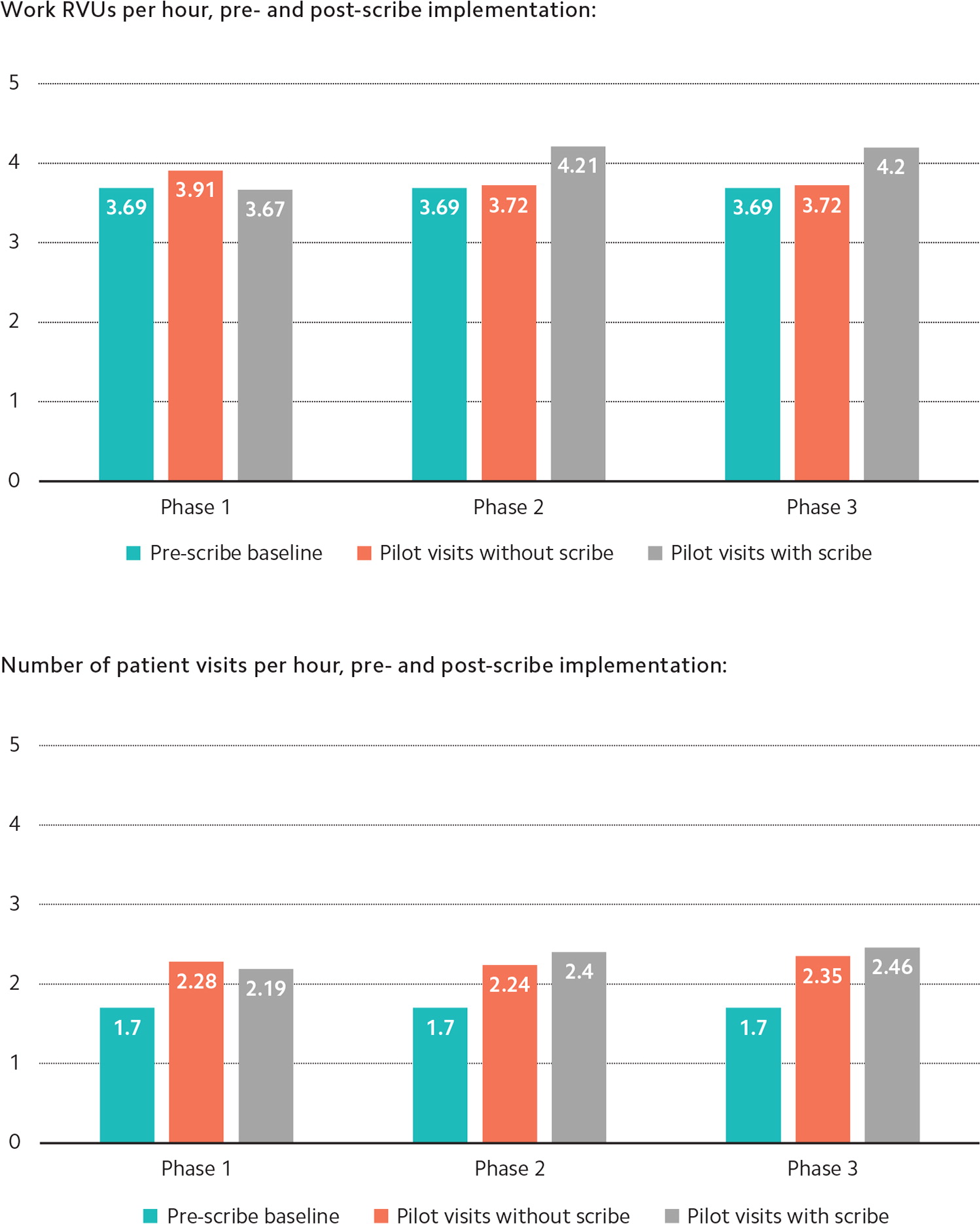

The pilot involved 11 physicians, four clinical sites, and three scribes. During three pilot phases, physicians worked some shifts with a scribe and some without, to allow for comparison and account for any efficiency and productivity changes that might have resulted from simply being involved in the pilot, such as new workflows.

In the two weeks of phase one, physicians were asked to maintain their usual patient volume. In the two weeks of phase two, they were asked to see one additional patient per four-hour session. In phase three — the final two weeks —they were asked to see two or more patients during their four-hour session.

Phase one revealed a decrease in work RVUs, likely due to the learning curve of a physician working with a new scribe. But after that, increases in both work RVUs and visits per hour were observed (see “Productivity results”). The expense of a scribe was covered by the increase in work RVUs of one extra patient per four-hour session. Doing this also increased staff and patient satisfaction, as the extra visit was considered a “same-day, urgent-type visit” that was added only after the scribe was present for the shift.

CASE STUDY: IN-HOUSE MEDICAL ASSISTANT SCRIBES

The University of Colorado implemented the Primary Care Redesign (previously called APEX) in 2015. For its in-house implementation model, the ratio of MAs to physicians or other clinicians was increased to 2.5:1, and the role of the MA was expanded to include setting the agenda with the patient; updating the past medical, surgical, and social histories; completing medication reconciliation; and closing any gaps in care.11,12 The MA also stayed during the patient visit to provide additional documentation assistance.11,12

This model improved quality metrics, decreased burnout, and increased patient access and volume.11,12 Burnout among physicians and other clinicians has averaged approximately 22% since implementation, and average MA burnout has been as low as 10%. Patient volume increased by an average of 1.5 patients per four-hour clinic session, which made this model cost neutral.

Once the model demonstrated success, the university expanded it to all the primary care clinics and some specialties in the University of Colorado Health System (UCHealth), which were then called “transformed practices.” Due to challenges with hiring and training the MAs, UCHealth implemented structural changes, such as salary market adjustments and centralized hiring, in order to meet demand.

Additionally, the university developed an MA academy to train all new MA hires on policies, procedures, and initial skill competency. This training consists of two sessions: Part one is for all MAs hired into the system, and part two is reserved for MAs who will work in transformed practices and need additional training on the expanded rooming process and in-room documentation support.

FACTORS TO CONSIDER FOR YOUR CLINIC

When deciding whether to add in-person documentation support to your clinic (and what type), take into consideration the following factors.

Finances. Outline the needs of your clinic, including any resources required to hire, train, oversee, and evaluate the program. Typically, an outsourced vendor medical scribe company will handle administrative issues, whereas an in-house program manages them internally. Evaluating the options based on both the short-term, up-front cost as well as long-term investment will help clinics determine which option is best for them (e.g., hourly cost of a service balanced with employee benefit costs). As noted earlier, in both the University of Michigan model of outsourced vendor scribes and the University of Colorado model of utilizing MAs for documentation support, cost neutrality was achieved by seeing one to 1.5 additional patients in a four-hour session.

Staffing. Turnover of scribes affects both models of in-person documentation support. The local hiring pool may also affect the type of service you consider, in terms of ability to recruit outsourced vendor scribes or add additional MAs.

Space and technology. Physical space in the clinic and exam room may be a concern. The types of visits your practice most commonly provides could help determine the best-fitting support. Data from the University of Colorado Primary Care Redesign indicates in-room support use varies by visit type, as providers elect not to use scribe support for certain visit types (see “Common visit types scribed by MAs via in-room documentation”). Hardware purchasing choices, such as additional laptops or tablets for in-person scribes and microphones or cameras for off-site documentation support, are other factors to consider.

Training. Some clinic-based training is needed in order to maximize efficiency of the physician-scribe team. Institutional compliance standards may affect the use of off-site scribing services, such as virtual scribes or third-party transcription services, as well as in-person scribing alternatives.

The bottom line is that, regardless of which model practices choose for in-person scribes (outsourced vendor scribes or in-house MA scribes), they can expect increased patient volume and increased physician and provider satisfaction.

COMMON VISIT TYPES SCRIBED BY MAs VIA IN-ROOM DOCUMENTATION

New patient visit

Hospital follow-up

Return patient visit

Pre-op visit

Preventive visit – adult

Preventive visit – pediatric