This supplement is sponsored by the American Academy of Family Physicians. This publication is funded under an unrestricted grant from Dynavax Technologies Corporation.

Fam Pract Manag. 2023;30(5):29-32

Introduction

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) currently recommends universal hepatitis B (HepB) vaccination for any individual from infancy through 59 years.1 The new recommendation follows the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) guidance, as they expanded their recommendations for HepB vaccination in April 2022 to include universal HepB vaccination for all adults 19–59 years. In this supplement, we'll explore these new recommendations, the history of HepB vaccines, U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved HepB vaccines and barriers to vaccine uptake through the lens of a clinical case study for our hypothetical patient, Jane Doe.

Clinical Case Study: Examining the Patient

Jane Doe is a 45-year-old cisgender, Latinx female presenting to a clinic for a wellness exam. Your conversation with her turns to routine health maintenance, so you scan the best practice alert in her chart and note she is due for a colonoscopy, cervical cancer screening, and a HepB vaccine. Surprised by the recommendation, since the patient doesn't have any risk factors for contracting the hepatitis B virus, you check the state immunization registry. You confirm in the registry that this patient has never had a documented HepB vaccine.

You ask Jane about this, and she shares that she grew up in the state where you practice and received all routine childhood immunizations. She lived out of state in college and graduate school and is uncertain if she had the HepB vaccine when she entered college 25 years ago, “with all the other pre-enrollment health stuff.”

Jane is not engaged in intravenous drug use, is in a monogamous relationship with a long-term partner (i.e., she's had one sexual partner in the last 15 years), and has no other known risk factors for HepB virus exposure. You're uncertain why the HepB vaccine was recommended in the electronic health record. Does this patient really need the HepB vaccine? You review the CDC recommendations when you step out of the exam room.

CDC Recommendations for HepB Vaccines

In 2022, the CDC expanded HepB vaccine recommendations to include universal immunization for adults 19–59 years.1,2 Adults >60 years with risk factors should still receive the HepB vaccine, and adults >60 years without risk factors may receive the HepB vaccine if they desire. Despite the changes to the HepB vaccine guidelines, many physicians remain unaware of this recommendation. To simplify the guidelines, the ACIP recommends the following individuals should receive HepB vaccination3:

All infants

Unvaccinated individuals <19 years

Adults 19–59 years

Adults >60 years with risk factors for HepB

The following groups may receive HepB vaccination:

Adults >60 years without known risk factors for HepB if they desire

Clinical Case Study: Exploring HepB Vaccine Options

Based on the guidelines, Jane Doe's health maintenance alert makes sense, and you order the HepB vaccine. You notice several options are available, including Engerix-B, PreHevbrio, and Heplisav-B. Some are newer vaccines you're unfamiliar with, so you're not sure which is the preferred HepB vaccine for your patient. You continue to explore the evidence and learn more about the different FDA-approved HepB vaccines.

Current FDA-Approved Vaccines for HepB

There are currently five FDA-approved HepB vaccines for use in adults. With the new recommendations for expanding to universal HepB vaccination for adults 19–59 years, the ACIP did not make preferential selection of any one vaccine product. The current HepB vaccine options are available as a 2- or 3-dose series as follows4:

3-dose series (0, 1, and 6 months)

– Recombivax HB

– Engerix-B

– Twinrix (provides immunization against HepA and HepB and may be given with an accelerated 4-dose schedule [0, 7 days, 21–30 days, and 12 months])

– PreHevbrio

2-dose series (0 and 1 month)

– Heplisav-B

There is insufficient evidence to recommend Heplisav-B or PreHevbrio for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, and the safety and effectiveness of both vaccines have not been established for patients on hemodialysis.4

Clinical Case Study: Reviewing the History of HepB Vaccines

After learning about newer HepB vaccine options, you select one suitable for Jane Doe from your health system formulary. The newer HepB vaccines prompt you to review their history in the United States and their effectiveness so you can share your confidence in this vaccine with your patients.

History of HepB Vaccines in the U.S

HepB vaccines were first recommended by the CDC in 1982 for populations at increased risk for hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, such as health care workers, men who have sex with men, and persons who inject drugs.5

To improve the reduction rates of HBV and subsequent morbidity and mortality, guidelines expanded to target patient populations multiple times over the last 41 years.5 In 1991, the ACIP recommended universal childhood vaccination with a special focus on preventing perinatal HBV, as well as targeting high-risk adolescent and adult patients. By 1999, the ACIP recommended universal vaccination of all children <19 years.

By expanding HepB vaccination to the routine pediatric immunization schedule, rates of immunization significantly increased among pediatric patients.5 From 1993 to 2000, HepB vaccination rates for infants 19–35 months increased from 16% to 90%, and adolescent coverage for children 13–15 years went from near zero to 67%. Following this remarkable increase in immunization rates, acute HBV infection rates decreased, demonstrating that comprehensive universal vaccination strategies effectively reduce HBV infection rates.5,6

Clinical Case Study: Identifying Barriers

Universal pediatric vaccine recommendations increased HepB vaccine rates at an impressive rate. You wonder to yourself if this success could be replicated for HepB vaccination rates for adults as you learn that most adults in the United States have not received the HepB vaccine. You begin to consider barriers to overcome to help increase HepB vaccination for your adult patients.

Barriers to Increase HepB Vaccination

The decades-long success of universal HepB vaccination recommendations for pediatric and adolescent patients could serve as a model for universal HepB vaccination for adults 19–59 years. However, data shows that despite the widespread availability of effective and well-accepted HepB vaccines, only 30% of adults have received a complete HepB vaccine series.7

The ACIP identified barriers to increasing HepB vaccination, including ineffective identification of adult patients most in need of vaccination. Addressing this challenge was one reason the ACIP recommended universal immunization of all adults 19–59 years.1 Not only does expanding coverage simplify clinical decision-making, but it also provides vaccination for the highest-risk age range of new HepB infections: adults 30–59 years.8 It's important to note that a substantial portion of this cohort of patients may have missed the universal recommendations for childhood vaccination in the 1990s.

Clinical Guidance to Address Barriers

By simply recommending universal HepB vaccination for adults, a significant barrier of identifying adult patients who are at an increased risk of HBV is addressed. Despite this simplification, physicians still face barriers to vaccinating their adult patients at the system-, physician-, and patient-levels. The following sections address common barriers to HepB vaccination and suggest how to best handle them at each level.

Patient-level Barriers

One barrier at the patient level to increasing vaccination is a lack of awareness of the importance of HepB vaccination. This can be addressed by physicians and health care teams providing brief education about HBV, including modes of transmission. Patients should also be made aware of the risks of developing chronic HBV, which can lead to liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, and even death.8

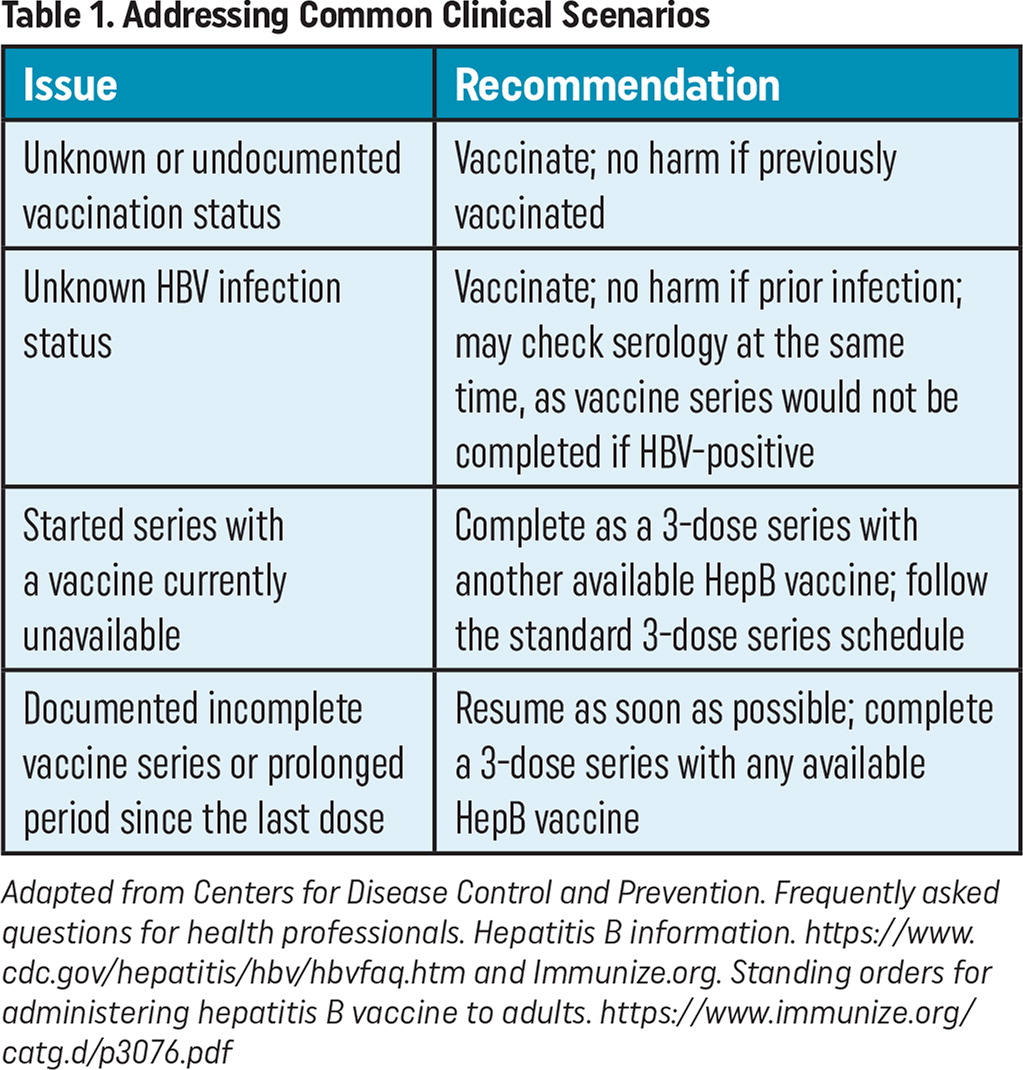

Another barrier is that patients could be uncertain of their vaccine status. If written documentation of prior HepB vaccination is unavailable, patients should be advised to receive vaccination as there is no risk for harm if they receive an additional HepB vaccine series.4

If a patient is uncertain about prior HBV infection, there is no need to postpone vaccination until prior exposure status is ascertained. Rather, the patient can start the HepB vaccine series immediately with HBV serology checked at the same visit.4 If their HBV serology showed a prior infection, the patient would not complete the series as there would be no benefit to the patient.

Some patients may withhold information about behaviors, increasing their risk for HBV due to concern about the impact on their relationship with your health care team. Universal HepB vaccination and vaccinating adults >60 years without risk factors can hopefully remove any stigma and this potential barrier of patients disclosing sensitive personal information.

Physician-level Barriers

With any new recommendation, it takes time for widespread adoption of guidelines. As physicians and their care teams increase awareness of the recommendations for universal HepB vaccination for adults 19–59 years, this should translate into improved vaccination rates. The current recommendations are simpler than previous guidelines, making them easier to implement.

For many physicians, time is a significant barrier to speaking with every patient about HepB vaccination. Removing the need to discuss HBV risk factors with every patient saves physicians and their care teams valuable time to address other medical needs.

Physicians and their care teams may be unfamiliar with newer vaccines, such as Heplisav-B and PreHevbrio, leading to uncertainty about which vaccine to offer patients. The ACIP states that any available HepB vaccine formulations may be used without preference for any patients except women who are pregnant or breastfeeding and patients on hemodialysis.4 These patients should not receive either Heplisav-B or PreHevbrio due to the lack of safety data for these newer vaccines on these patient populations.

Physicians and their care teams may find incomplete vaccination series for patients who started a HepB vaccine series but never had documented the completion of the series. In this scenario, patients do not need to start their vaccine series over.4 Rather, care teams should complete a patient's 3-dose series, resuming from the last documented vaccine with any available HepB vaccine. The second dose (if needed) should be given as soon as possible (at least 4 weeks after the 1st dose), and the 3rd dose should be given a minimum of 8 weeks after the second dose and a minimum of 16 weeks after the first dose. If only a 3rd dose is needed, it should be given a minimum of 8 weeks after the 2nd dose and 16 weeks after the first dose.

| Issue | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Unknown or undocumented vaccination status | Vaccinate; no harm if previously vaccinated |

| Unknown HBV infection status | Vaccinate; no harm if prior infection; may check serology at the same time, as vaccine series would not be completed if HBV-positive |

| Started series with a vaccine currently unavailable | Complete as a 3-dose series with another available HepB vaccine; follow the standard 3-dose series schedule |

| Documented incomplete vaccine series or prolonged period since the last dose | Resume as soon as possible; complete a 3-dose series with any available HepB vaccine |

System-level Barriers

Increasing access to HepB vaccinations is well suited for system-level interventions. Health systems should implement delegation protocols and standing orders to remove unnecessary barriers to vaccination, such as those recommended at Immunize.org.9 This will empower all health care team members to identify and vaccinate patients needing HepB vaccination, further saving the care team time.

Health systems should also leverage technology by triggering EHR alerts to identify individuals without documented completion of the HepB vaccine series. This prompt, via a best practice alert during clinical encounters, could remind the care team to offer the HepB vaccine to patients who are unvaccinated.

Health maintenance alerts in the patient care portal are also helpful to inform patients who are unvaccinated of their need to receive the HepB vaccine. Raising patient awareness about recommended HepB immunizations may prompt patients to contact the clinic to receive the HepB vaccine at a future visit.

Since each HepB vaccine is part of a series, it is a best practice to ensure the subsequent vaccine is scheduled when receiving the current immunization.10 Having the patient schedule when they will return for their next vaccine before leaving the clinic improves the completion of the entire series.

Clinical Case Study: Resolving the Visit

After reviewing the updated CDC guidelines and FDA-approved HepB vaccines, you return to the exam room and inform Jane Doe that you strongly recommend the HepB vaccination. Even without increased risk factors for contracting HBV, she should receive the HepB vaccine since the CDC recommends universal HepB vaccination for everyone through 59 years.

Despite the uncertainty about Jane's prior HepB vaccination, providing her with a vaccine today is safe. She is appreciative you took the time to review the current guidelines and vaccine options and is willing to get her HepB vaccine today. Before leaving the clinic, your care team schedules the appointment for her next shot in one month, and Jane Doe completes the rest of the HepB vaccine series as scheduled.