Fam Pract Manag. 2025;32(3):37-38

The publication of this content is funded by West Health Foundation and brought to you by the AAFP. Journal editors were not involved in the development of this content.

More than 10% of people over 65 years and one-third of those over 85 live with dementia due to Alzheimer's disease.1 It is the most common cause of dementia, but several other diseases cause dementia as well. With too few specialists to evaluate the growing number of patients with cognitive concerns, primary care needs a structured approach for evaluation. This supplement summarizes a six-step validated approach shown to be effective in primary care.2

Despite evidence that making a diagnosis leads to better care, nearly 40% of dementia cases remain undiagnosed.3 Primary care teams should be aware of the warning signs of cognitive impairment and differentiate those signs from normal changes with aging. Concerns more likely to be part of normal aging include often misplacing items or taking longer to remember someone's name.4 Changes in behavior that should raise serious concerns of mild cognitive impairment or dementia include asking the same question 30 minutes later, trouble completing a complex task that used to be easy or becoming disoriented in a familiar place.

Evaluation in Primary Care

An evaluation of cognition is best performed at a dedicated patient visit, ideally with a family member or close friend present. More than one visit may be required to evaluate some patients thoroughly.

STEP 1: EVALUATE FOR CAUSATIVE AND CONTRIBUTING FACTORS

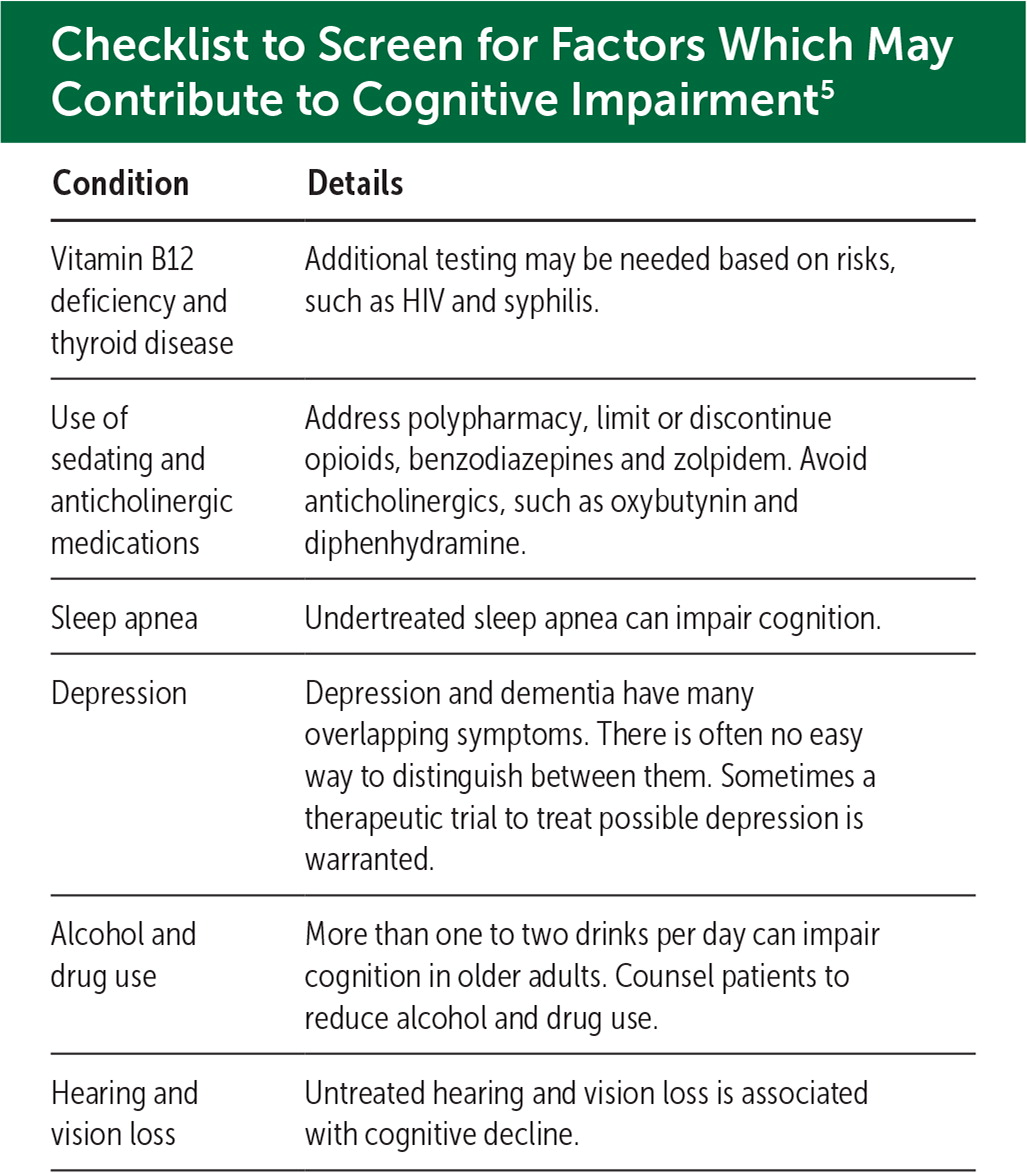

Common factors which may contribute to cognitive impairment are listed in the table. Addressing these factors can often improve cognition.

| Condition | Details |

|---|---|

| Vitamin B12 deficiency and thyroid disease | Additional testing may be needed based on risks, such as HIV and syphilis. |

| Use of sedating and anticholinergic medications | Address polypharmacy, limit or discontinue opioids, benzodiazepines and zolpidem. Avoid anticholinergics, such as oxybutynin and diphenhydramine. |

| Sleep apnea | Undertreated sleep apnea can impair cognition. |

| Depression | Depression and dementia have many overlapping symptoms. There is often no easy way to distinguish between them. Sometimes a therapeutic trial to treat possible depression is warranted. |

| Alcohol and drug use | More than one to two drinks per day can impair cognition in older adults. Counsel patients to reduce alcohol and drug use. |

| Hearing and vision loss | Untreated hearing and vision loss is associated with cognitive decline. |

STEP 2: PERFORM A COGNITIVE TEST

STEP 3: OBTAIN COLLATERAL HISTORY

When possible, interviewing a person close to the patient is essential for assessing cognitive changes and their impact on activities of daily living. A standardized questionnaire such as the Ascertain Dementia 8 Screening Interview can help guide this interview.8

STEP 4: IMAGING

Imaging is performed to rule out an intracranial mass, hydrocephalus or subdural hematoma.9 Magnetic resonance imaging is preferred for its greater detail, but a computed tomography scan may be better tolerated for patients with difficulty staying still.

STEP 5: MAKE A DIAGNOSIS

Patients who have gradual cognitive changes over time leading to loss of independence with ADLs and a MoCA score of less than 20 should be diagnosed with dementia.10 When significant cognitive changes have occurred over time and the MoCA score is 20 to 25 but the patient is still independent with their ADLs, MCI should be diagnosed. Studies indicate that patients with MCI have a high cumulative risk of progressing to dementia.11

Several disease processes may cause MCI or dementia, the most common being Alzheimer's disease.1 Older patients often have a mixed cause of cognitive impairment. It is often not possible to clinically determine a specific underlying cause of dementia. Blood-based biomarkers are emerging as a tool in evaluating the etiology of MCI or dementia. A positive blood-based biomarker in those who do not have a diagnosis of MCI or dementia is of unknown clinical significance.12

STEP 6: CONSIDER SPECIALTY REFERRAL

Visual hallucinations, symptom onset before 65 years, atypical neurologic symptoms or an interest in considering anti-amyloid therapy should prompt more urgent specialty consultation.13 Visual hallucinations suggest Lewy body disease, which is a complex diagnosis with important clinical implications.

Follow-up Care for Patients and Caregivers

At follow-up visits, primary care providers can promote brain health and safety, encourage advance directives and connect patients and their families to resources such as the Alzheimer's Association (https://www.alz.org/professionals) and Best Programs for Caregiving (https://bpc.caregiver.org/).

Medications

Although medications, such as donepezil and memantine, have limited efficacy, it is reasonable to offer a trial of these medications to patients with dementia.14,15 Newer anti-amyloid medications (e.g., lecanemab and donanemab) have been shown to slow the progression of Alzheimer's disease by about 4–6 months during 18-month trials.16,17 Patients must have MCI or mild dementia due to Alzheimer's disease to be eligible. Side effects may include brain bleeding or swelling.18 Avoid antipsychotic medications for behavioral symptoms when possible due to their potential harm, with non-pharmacologic therapies tried instead.19

Summary

Either MCI or dementia can be a difficult diagnosis for patients and their families to receive, but early diagnosis by PCPs can lead to better, less chaotic care. Physicians should recognize the warning signs of cognitive impairment, treat contributing factors, diagnose MCI and dementia and help manage these diseases as they progress. For additional training about this important topic, please visit the AAFP's free continuing medical education video series, Cognitive Care in Family Medicine Settings (https://www.aafp.org/cme/all/neurology/cognitive-care-fm-settings.html).