Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(11):896-903

Related letter: Lymphadenopathy in Children and Young Adults May Be Due to a Periodic Fever Syndrome

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Lymphadenopathy is benign and self-limited in most patients. Etiologies include malignancy, infection, and autoimmune disorders, as well as medications and iatrogenic causes. The history and physical examination alone usually identify the cause of lymphadenopathy. When the cause is unknown, lymphadenopathy should be classified as localized or generalized. Patients with localized lymphadenopathy should be evaluated for etiologies typically associated with the region involved according to lymphatic drainage patterns. Generalized lymphadenopathy, defined as two or more involved regions, often indicates underlying systemic disease. Risk factors for malignancy include age older than 40 years, male sex, white race, supraclavicular location of the nodes, and presence of systemic symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and unexplained weight loss. Palpable supraclavicular, popliteal, and iliac nodes are abnormal, as are epitrochlear nodes greater than 5 mm in diameter. The workup may include blood tests, imaging, and biopsy depending on clinical presentation, location of the lymphadenopathy, and underlying risk factors. Biopsy options include fine-needle aspiration, core needle biopsy, or open excisional biopsy. Antibiotics may be used to treat acute unilateral cervical lymphadenitis, especially in children with systemic symptoms. Corticosteroids have limited usefulness in the management of unexplained lymphadenopathy and should not be used without an appropriate diagnosis.

Lymphadenopathy refers to lymph nodes that are abnormal in size (e.g., greater than 1 cm) or consistency. Palpable supraclavicular, popliteal, and iliac nodes, and epitrochlear nodes greater than 5 mm, are considered abnormal. Hard or matted lymph nodes may suggest malignancy or infection. In primary care practice, the annual incidence of unexplained lymphadenopathy is 0.6%.1 Only 1.1% of these cases are related to malignancy, but this percentage increases with advancing age.1 Cancers are identified in 4% of patients 40 years and older who present with unexplained lymphadenopathy vs. 0.4% of those younger than 40 years.1 Etiologies of lymphadenopathy can be remembered with the MIAMI mnemonic: malignancies, infections, autoimmune disorders, miscellaneous and unusual conditions, and iatrogenic causes (Table 1).2,3 In most cases, the history and physical examination alone identify the cause.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonography should be used as the initial imaging modality for children up to 14 years presenting with a neck mass with or without fever. | C | 15 |

| Computed tomography should be used as the initial imaging modality for children older than 14 years and adults presenting with solitary or multiple neck masses. | C | 15 |

| In children with acute unilateral anterior cervical lymphadenitis and systemic symptoms, empiric antibiotics that target Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococci may be given. | C | 17 |

| Corticosteroids should be avoided until a definitive diagnosis of lymphadenopathy is made because they could potentially mask or delay histologic diagnosis of leukemia or lymphoma. | C | 4 |

| Fine-needle aspiration may be used to differentiate malignant from reactive lymphadenopathy. | C | 19–22 |

| Malignancies |

| Kaposi sarcoma, leukemias, lymphomas, metastases, skin neoplasms |

| Infections |

| Bacterial: brucellosis, cat-scratch disease (Bartonella), chancroid, cutaneous infections (staphylococcal or streptococcal), lymphogranuloma venereum, primary and secondary syphilis, tuberculosis, tularemia, typhoid fever |

| Granulomatous: berylliosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, silicosis |

| Viral: adenovirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis, herpes zoster, human immunodeficiency virus, infectious mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus), rubella |

| Other: fungal, helminthic, Lyme disease, rickettsial, scrub typhus, toxoplasmosis |

| Autoimmune disorders |

| Dermatomyositis, rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, Still disease, systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Miscellaneous/unusual conditions |

| Angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia (Castleman disease), histiocytosis, Kawasaki disease, Kikuchi lymphadenitis, Kimura disease, sarcoidosis |

| Iatrogenic causes |

| Medications, serum sickness |

History

Factors that can assist in identifying the etiology of lymphadenopathy include patient age, duration of lymphadenopathy, exposures, associated symptoms, and location (localized vs. generalized). Table 2 lists common historical clues and their associated diagnoses.2 Other historical questions include asking about time course of enlargement, tenderness to palpation, recent infections, recent immunizations, and medications.4

| Historical clues | Suggested diagnoses | Initial testing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever, night sweats, weight loss, or node located in supraclavicular, popliteal, or iliac region, bruising, splenomegaly | Leukemia, lymphoma, solid tumor metastasis | CBC, nodal biopsy or bone marrow biopsy; imaging with ultrasonography or computed tomography may be considered but should not delay referral for biopsy | |

| Fever, chills, malaise, sore throat, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea; no other red flag symptoms | Bacterial or viral pharyngitis, hepatitis, influenza, mononucleosis, tuberculosis (if exposed), rubella | Limited illnesses may not require any additional testing; depending on clinical assessment, consider CBC, monospot test, liver function tests, cultures, and disease-specific serologies as needed | |

| High-risk sexual behavior | Chancroid, HIV infection, lymphogranuloma venereum, syphilis | HIV-1/HIV-2 immunoassay, rapid plasma reagin, culture of lesions, nucleic acid amplification for chlamydia, migration inhibitory factor test | |

| Animal or food contact | |||

| Cats | Cat-scratch disease (Bartonella) | Serology and polymerase chain reaction | |

| Toxoplasmosis | Serology | ||

| Rabbits, or sheep or cattle wool, hair, or hides | Anthrax | Per CDC guidelines | |

| Brucellosis | Serology and polymerase chain reaction | ||

| Tularemia | Blood culture and serology | ||

| Undercooked meat | Anthrax | Per CDC guidelines | |

| Brucellosis | Serology and polymerase chain reaction | ||

| Toxoplasmosis | Serology | ||

| Recent travel, insect bites | Diagnoses based on endemic region | Serology and testing as indicated by suspected exposure | |

| Arthralgias, rash, joint stiffness, fever, chills, muscle weakness | Rheumatoid arthritis, Sjögren syndrome, dermatomyositis, systemic lupus erythematosus | Antinuclear antibody, anti-doubled-stranded DNA, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CBC, rheumatoid factor, creatine kinase, electromyography, or muscle biopsy as indicated | |

AGE AND DURATION

About one-half of otherwise healthy children have palpable lymph nodes at any one time.4 Most lymphadenopathy in children is benign or infectious in etiology. In adults and children, lymphadenopathy lasting less than two weeks or greater than 12 months without change in size has a low likelihood of being neoplastic.2,5 Exceptions include low-grade Hodgkin lymphomas and indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma, although both typically have associated systemic symptoms.6

EXPOSURES

Environmental, travel-related, animal, and insect exposures should be ascertained. Chronic medication use, infectious exposures, immunization status, and recent immunizations should be reviewed as well. Table 3 lists medications commonly associated with lymphadenopathy.2 Tobacco and alcohol use and ultraviolet radiation exposure increase concerns for neoplasm. An occupational history that includes mining, masonry, and metal work may elicit work-related etiologies of lymphadenopathy, such as silicon or beryllium exposure. Asking about sexual history to assess exposure to genital sores or participation in oral intercourse is important, especially for inguinal and cervical lymphadenopathy. Finally, family history may identify familial causes of lymphadenopathy, such as Li-Fraumeni syndrome or lipid storage diseases.2

| Allopurinol |

| Atenolol |

| Captopril |

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol) |

| Gold |

| Hydralazine |

| Penicillins |

| Phenytoin (Dilantin) |

| Primidone (Mysoline) |

| Pyrimethamine (Daraprim) |

| Quinidine |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole |

| Sulindac |

ASSOCIATED SYMPTOMS

A thorough review of systems aids in identifying any red flag symptoms. Arthralgias, muscle weakness, and rash suggest an autoimmune etiology. Constitutional symptoms of fever, chills, fatigue, and malaise indicate an infectious etiology. In addition to fever, drenching night sweats and unexplained weight loss of greater than 10% of body weight may suggest Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.2,3,6

Physical Examination

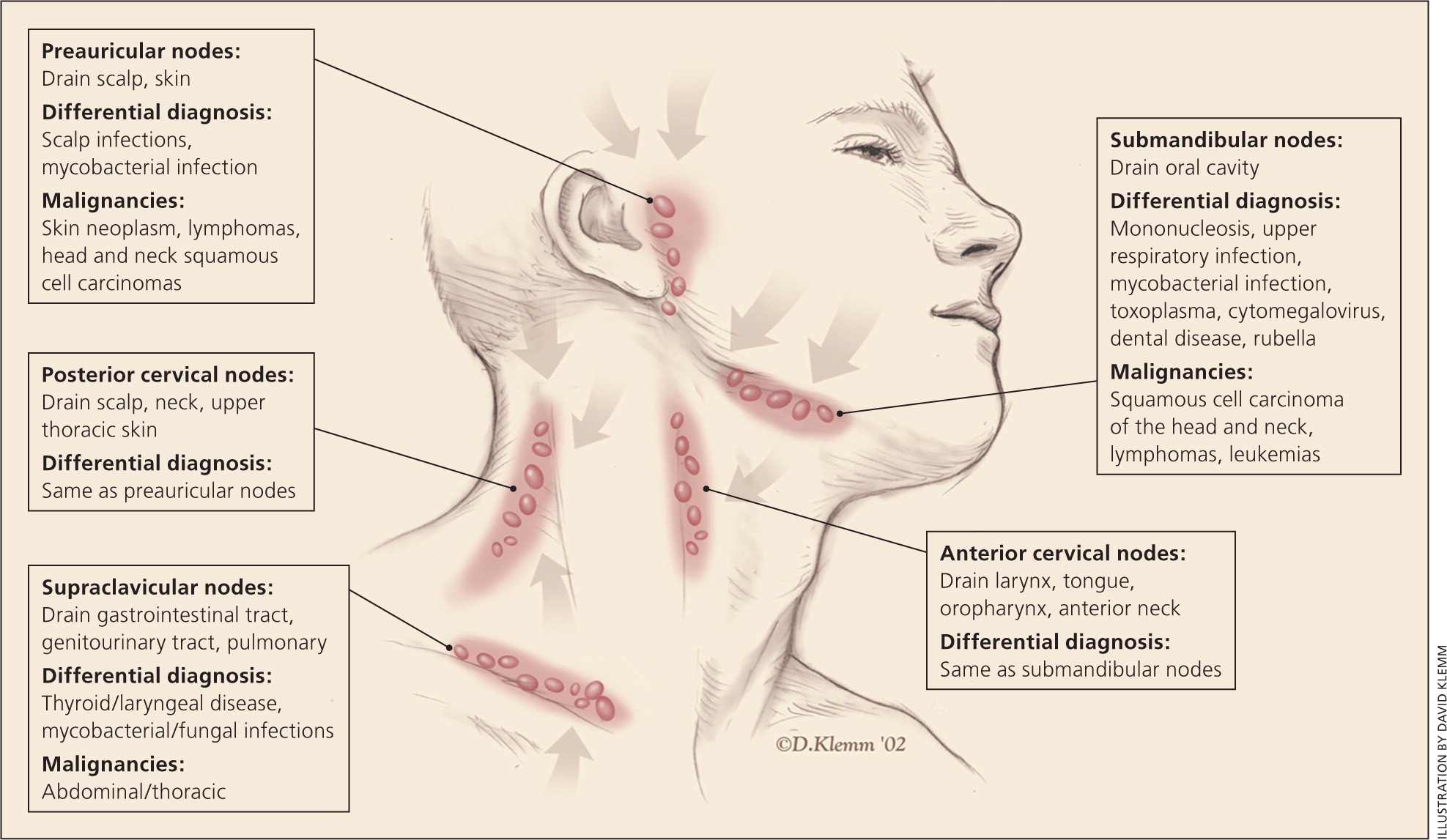

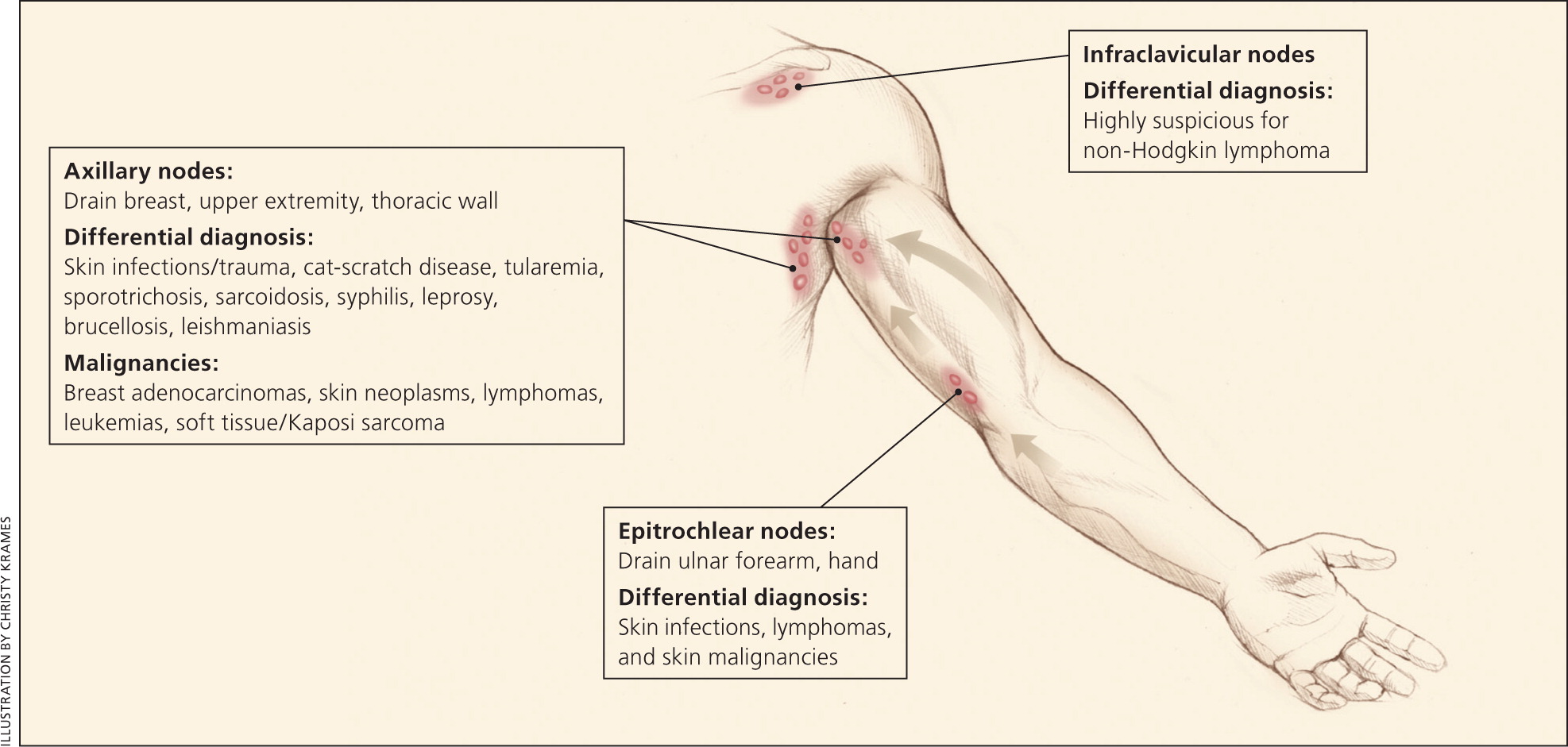

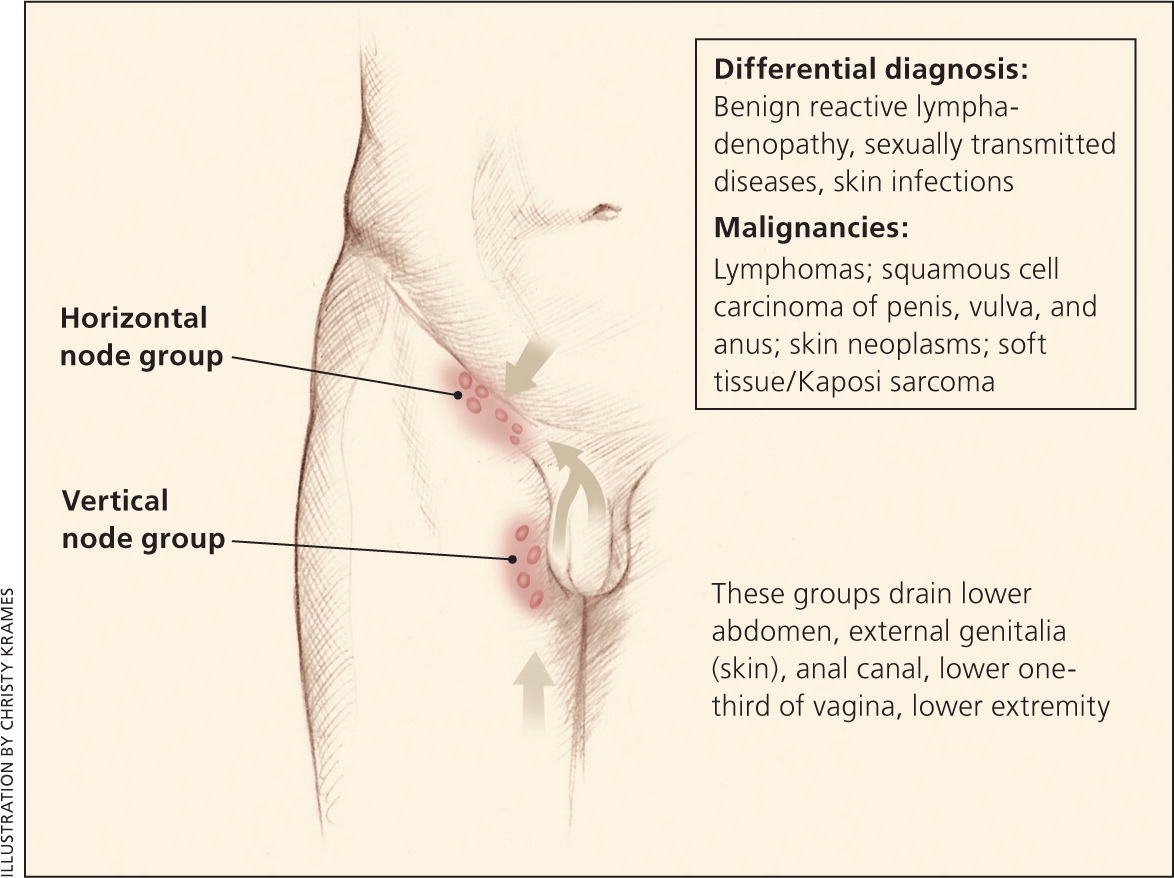

Overall state of health and height and weight measurements may help identify signs of chronic disease, especially in children.7 A complete lymphatic examination should be performed to rule out generalized lymphadenopathy, followed by a focused lymphatic examination with consideration of lymphatic drainage patterns. Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3 demonstrate typical lymphatic drainage patterns, as well as common etiologies of lymphadenopathy in these regions.2 A skin examination should be performed to rule out other lesions that would point to malignancy and to evaluate for erythematous lines along nodal tracts or any trauma that could lead to an infectious source of the lymphadenopathy. Finally, abdominal examination focused on splenomegaly, although rarely associated with lymphadenopathy, may be useful for detecting infectious mononucleosis, lymphocytic leukemias, lymphoma, or sarcoidosis.2,5

NODAL CHARACTER AND SIZE

The quality and size of lymph nodes should be assessed. Lymph node qualities include warmth, overlying erythema, tenderness, mobility, fluctuance, and consistency. Shotty lymphadenopathy is the presence of multiple small lymph nodes that feel like “buck shots” under the skin.8 This usually implies reactive lymphadenopathy from viral infection. A painless, hard, irregular mass or a firm, rubbery lesion that is immobile or fixed may represent a malignancy, although in general, qualitative characteristics are unable to reliably predict malignancy. Painful or tender lymphadenopathy is nonspecific and may represent possible inflammation caused by infection, but it can also be the result of hemorrhage into a node or necrosis.3 No specific nodal size is indicative of malignancy.3

Localized Lymphadenopathy

HEAD AND CERVICAL

Head and neck lymphadenopathy can be classified as submental, submandibular, anterior or posterior cervical, preauricular, and supraclavicular.9 Infection is a common cause of head and cervical lymphadenopathy. In children, acute and self-limiting viral illnesses are the most common etiologies of lymphadenopathy.2 Inflamed cervical nodes that progress quickly to fluctuation are typically caused by staphylococcal and streptococcal infections and require antibiotic therapy with occasional incision and drainage. Persistent lymphadenopathy lasting several months can be caused by atypical mycobacteria, cat-scratch disease, Kikuchi lymphadenitis, sarcoidosis, and Kawasaki disease, and often can be mistaken for neoplasms.2,7 Supraclavicular adenopathy in adults and children is associated with high risk of intra-abdominal malignancy and must be evaluated promptly. Studies found that 34% to 50% of these patients had malignancy, with patients older than 40 years at highest risk.9,10

AXILLARY

Infections or injuries of the upper extremities are a common cause of axillary lymphadenopathy. Common infectious etiologies are cat-scratch disease, tularemia, and sporotrichosis due to inoculation and lymphatic drainage. Absence of an infectious source or traumatic lesions is highly suspicious for a malignant etiology such as Hodgkin lymphoma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Breast, lung, thyroid, stomach, colorectal, pancreatic, ovarian, kidney, and skin cancers (malignant melanoma) can metastasize to the axilla.3,5 Silicone breast implants may also cause axillary lymphadenopathy because of an inflammatory reaction to silicone particles from implant leakage.11

EPITROCHLEAR

INGUINAL

Inguinal lymphadenopathy, with nodes up to 2 cm in diameter, is present in many healthy adults. It is more common in those who walk outdoors barefoot, especially in tropical regions.3,12 Common etiologies include sexually transmitted infections such as herpes simplex, lymphogranuloma venereum, chancroid, and syphilis, and lower extremity skin infections. Lymphomas, both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin, typically do not present in the inguinal region.13 Other inguinal lymphadenopathy–associated malignancies are penile and vulvar squamous cell carcinomas and melanoma. Inguinal lymphadenopathy is present in about one-half of penile or urethral carcinomas.14

Generalized Lymphadenopathy

Generalized lymphadenopathy is the enlargement of more than two noncontiguous lymph node groups.8 Significant systemic disease from infections, autoimmune diseases, or disseminated malignancy often causes generalized lymphadenopathy, and specific testing is necessary to determine the diagnosis. Benign causes of generalized lymphadenopathy are self-limited viral illnesses, such as infectious mononucleosis, and medications. Other causes include acute human immunodeficiency virus infection, activated mycobacterial infection, cryptococcosis, cytomegalovirus, Kaposi sarcoma, and systemic lupus erythematosus. Generalized lymphadenopathy can occur with leukemias, lymphomas, and advanced metastatic carcinomas.3

Diagnostic Approach

Figure 4 provides an algorithm for evaluating lymphadenopathy.2 If history and physical examination findings suggest a benign or self-limited process, reassurance can be provided and follow-up arranged if lymphadenopathy persists. Findings suggestive of infectious or autoimmune etiologies may require specific testing and treatment as indicated. If malignancy is considered unlikely based on history and physical examination, localized lymphadenopathy can be observed for four weeks. Generalized lymphadenopathy should prompt routine laboratory testing and testing for autoimmune and infectious causes.2

Radiologic evaluation with computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasonography may help to characterize lymphadenopathy. The American College of Radiology recommends ultrasonography as the initial imaging choice for cervical lymphadenopathy in children up to 14 years of age and computed tomography for persons older than 14 years.15 Based on the location of the abnormal nodes, the sensitivity of these modalities for diagnosing metastatic lymph nodes varies; therefore, history and clinical examination must guide selection.16 If the diagnosis is still uncertain, biopsy is recommended.

In children with acute unilateral anterior cervical lymphadenitis and systemic symptoms, antibiotics may be prescribed. Empiric antibiotics should target Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococci. Options include oral cephalosporins, amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin), orclindamycin.17 Corticosteroids should be avoided until a definitive diagnosis is made because treatment could potentially mask or delay histologic diagnosis of leukemia or lymphoma.5

Biopsy

Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) and core needle biopsy can aid in the diagnostic evaluation of lymph nodes when etiology is unknown or malignant risk factors are present (Table 44,6,10 ). FNA cytology is a quick, accurate, minimally invasive, and safe technique to evaluate patients and aid in triage of unexplained lymphadenopathy.18 If a reactive lymph node is likely, core needle biopsy can be avoided, and FNA used alone. Combined, they allow cytologic and histopathologic assessment of lymph nodes. However, the use of both techniques may not be needed because the diagnostic accuracy of FNA in adult populations has been reported to approach 90%, with a sensitivity and specificity of 85% to 95% and 98% to 100%, respectively.19,20 False-positive diagnoses are rare with FNA. False-negative results occur secondary to early or partial involvement of lymph nodes, inexperience with lymph node cytology, unrecognized lymphomas with heterogeneity, and sampling errors.20 There are concerns about the reliability of FNA in the diagnosis of diseases such as lymphoma because it is unable to assess lymph node architecture. Regardless, FNA may be a useful triage tool for differentiating benign reactive lymphadenopathy from malignancy.21

| Age older than 40 years |

| Duration of lymphadenopathy greater than four to six weeks |

| Generalized lymphadenopathy (two or more regions involved) |

| Male sex |

| Node not returned to baseline after eight to 12 weeks |

| Supraclavicular location |

| Systemic signs: fever, night sweats, weight loss, hepatosplenomegaly |

| White race |

Open excisional biopsy remains a diagnostic option for patients who do not wish to undergo additional procedures. When selecting nodes for any method, the largest, most suspicious, and most accessible node should be sampled. Inguinal nodes typically display the lowest yield, and supraclavicular nodes have the highest.22,23

This review updates previous articles on this topic by Bazemore and Smucker2 and Ferrer.24

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries. Key terms: lymphadenopathy, peripheral, generalized, evaluation, treatment, imaging, management. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Clinical Evidence, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane database. Reference lists of retrieved articles were also searched. Search dates: September 2015 and July 2016.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Air Force Medical Department or the U.S. Air Force at large.