A more recent article on lumbar spinal stenosis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(8):1825-1834

Patient information: See related handout on lumbar spinal canal stenosis, written by the authors of this article.

Lumbar spine stenosis most commonly affects the middle-aged and elderly population. Entrapment of the cauda equina roots by hypertrophy of the osseous and soft tissue structures surrounding the lumbar spinal canal is often associated with incapacitating pain in the back and lower extremities, difficulty ambulating, leg paresthesias and weakness and, in severe cases, bowel or bladder disturbances. The characteristic syndrome associated with lumbar stenosis is termed neurogenic intermittent claudication. This condition must be differentiated from true claudication, which is caused by atherosclerosis of the pelvofemoral vessels. Although many conditions may be associated with lumbar canal stenosis, most cases are idiopathic. Imaging of the lumbar spine performed with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging often demonstrates narrowing of the lumbar canal with compression of the cauda equina nerve roots by thickened posterior vertebral elements, facet joints, marginal osteophytes or soft tissue structures such as the ligamentum flavum or herniated discs. Treatment for symptomatic lumbar stenosis is usually surgical decompression. Medical treatment alternatives, such as bed rest, pain management and physical therapy, should be reserved for use in debilitated patients or patients whose surgical risk is prohibitive as a result of concomitant medical conditions.

Low back pain resulting from degenerative disease of the lumbosacral spine is a major cause of morbidity, disability and lost productivity. Up to 90 percent of the U.S. population may have significant low back pain at some point.1 In 1984, it was estimated that over 5 million persons were incapacitated as a result of lower back pain.2 The financial impact in terms of health care dollars and lost work hours reaches billions of dollars each year in this country.3 With the increasing longevity of our population and a continually climbing proportion of middle-aged and elderly persons, the problem of lumbosacral pain is a significant health care issue. A ubiquitous and potentially disabling cause of osteoarthritic pain of the lower back and legs is stenosis of the lumbar spinal canal. This treatable condition is often a major cause of inactivity, loss of productivity and, potentially, loss of independence in many persons, particularly older persons.

Because of the slow progression of the disease, the diagnosis may be significantly delayed. Given the potentially devastating effects of this condition, rapid diagnosis and treatment are essential if patients are to be returned to their previous levels of activity.

Normal Anatomy

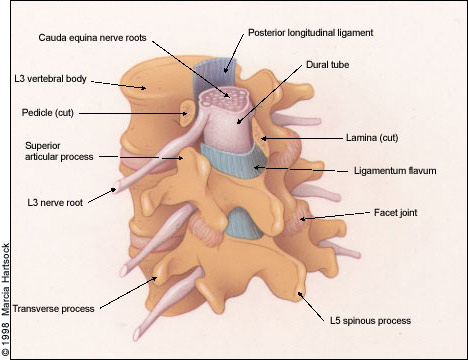

The lumbar vertebral canal is roughly triangular in shape and is narrowest in its anteroposterior diameter in the axial plane. The average anteroposterior diameter of the lumbar canal in adults, as determined by anatomic and radiographic studies, ranges from 15 to 23 mm.4 The canal is bounded anteriorly by the posterior edge of the vertebral body including the posterior longitudinal ligament, which is closely apposed to the posterior vertebral body surface, laterally by the pedicles, posterolaterally by the facet joints and articular capsules, and posteriorly by the lamina and ligamenta flava (yellow ligaments).

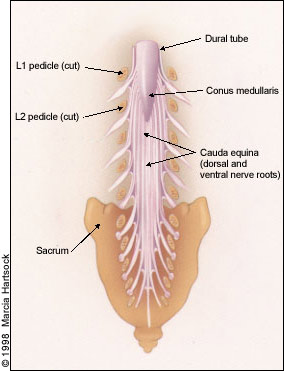

As shown in Figures 1 and 2, entrapment of the cauda equina roots, which pass within the dural sac, can occur as a result of progressive hypertrophy of any of the osseocartilaginous and ligamentous elements surrounding the spinal canal. Moreover, the intervertebral disc, which is composed of a gelatinous, centrally located nucleus pulposus and a peripherally located annulus fibrosus, is prone to rupture or herniate posteriorly or posterolaterally as a result of degenerative changes or trauma, producing neural element compromise.

In the lumbar regions, the cone-shaped terminus of the spinal cord (conus medullaris) normally ends at about the L1 or L2 level in adults. Caudal to these levels, the roots of the cauda equina are contained within the subarachnoid space of the dura-enclosed thecal sac (Figure 3). Thus, canal stenosis at lumbar levels results in nerve root dysfunction rather than spinal cord dysfunction.

Pathophysiology

Narrowing of the lumbar canal has many potential causes, and various classification schemes have been devised in order to better describe the pathophysiology of this condition. A classification system proposed by Verbiest5 categorizes the multiple causes of lumbar stenosis into two types: conditions that lead to progressive bony encroachment of the lumbar canal (including developmental, congenital, acquired and idiopathic causes) or stenosis produced by nonosseous structures such as ligaments, intervertebral discs and other soft tissue masses. For practical purposes, however, the etiologies of lumbar stenosis can be divided into congenital or acquired forms.

Few causes of lumbar stenosis are truly congenital. Narrowed or “shallow” lumbar canals may be a result of congenitally short pedicles, thickened lamina and facets, or excessive scoliotic or lordotic curves. These anatomic changes may lead to clinically significant stenosis if additional elements such as herniated intervertebral discs or other space-occupying lesions further narrow the canal and contribute to the compression. Verbiest5,6 noted that lumbar canal diameters from 10 to 12 mm may be associated with claudication if additional elements encroach on the canal, and he referred to this type of stenosis as “relative” canal stenosis.5–7

In most cases, stenosis of the lumbar canal may be attributed to acquired degenerative or arthritic changes of the intervertebral discs, ligaments and facet joints surrounding the lumbar canal. These changes include cartilaginous hypertrophy of the articulations surrounding the canal, intervertebral disc herniations or bulges, hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and osteophyte formation.

Some investigators have postulated that the pathologic changes that result in lumbar canal stenosis are the result of so-called micro-instability at the articular surfaces surrounding the canal.7 Micro-instability refers to minute, abnormal repetitive motion of the joints that link adjacent vertebra. These movements are clinically silent yet may result in progressive loss of strength in the joint capsules and lead to reactive bony and cartilaginous hypertrophy, thickening or calcification of the ligamentum flavum, or subluxation of one vertebra on another (spondylolisthesis), all of which may contribute to narrowing of the lumbar canal.

Compression of the microvasculature of the lumbar nerve roots, resulting in ischemia, is believed to be a major contributing factor in the development of neurogenic claudication. Wilson8 classified neurogenic claudication into two major types based on the putative pathophysiologic mechanism: postural or ischemic. Postural neurogenic claudication is induced when the lumbar spine is extended and lordosis is accentuated, whether at rest or during exercise in the erect posture. With extension of the spine, degenerated intervertebral discs and thickened ligamenta flava protrude posteriorly into the lumbar canal, producing transient compression of the cauda equina. In the ischemic form, it is theorized that transient ischemia occurs in compressed lumbosacral roots when increased oxygen demand occurs during walking.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical History

Men are affected with slightly higher frequency than women. Although symptomatic lumbar stenosis is usually a disease of the middle-aged and the elderly, younger patients may also be affected. Typically, the earliest complaint is back pain, which is relatively nonspecific and may result in delayed diagnosis. Patients then often experience leg fatigue, pain, numbness and weakness, sometimes several months to years after the back pain was first noticed. Patients may undergo minor trauma that can exacerbate symptoms, which may lead to a more rapid diagnosis.

Once the leg pain begins, it is most commonly bilateral, involving the buttocks and thighs and spreading distally toward the feet, typically with the onset and progression of leg exercise. In some patients, the pain, paresthesias and/or weakness are limited to the lower legs and feet, remaining present until movement ceases. The lower extremity symptoms are almost always described as burning, cramping, numbness, tingling or dull fatigue in the thighs and legs. Disease onset is usually insidious; early symptoms may be mild and progress to become extremely disabling. Symptom severity does not always correlate with the degree of lumbar canal narrowing.

Classically, the symptoms of lumbar canal stenosis begin or worsen with the onset of ambulation or by standing, and are promptly relieved by sitting or lying down. Thigh or leg pain typically precedes the onset of numbness and motor weakness. Along with numbness and weakness, these symptoms and signs constitute the syndrome of neurogenic intermittent claudication. Patients commonly complain of difficulty walking even short distances and do so with a characteristic stooped or anthropoid posture in more advanced cases. Although standing and walking exacerbate the extreme discomfort, bicycle riding can often be performed without much difficulty because of the theoretic widening of the lumbar canal that occurs with flexion of the back. Some patients actually obtain transient relief of pain by assuming a squatting position, which flexes the trunk. Conversely, lying prone or in any position that extends the lumbar spine exacerbates the symptoms, presumably because of ventral in-folding of the ligamentum flavum in a canal already significantly narrowed by degenerative osseus changes.

Other common symptoms include stiffness of the thighs and legs, back pain (which may be a constant symptom) and, in severe cases, visceral disturbances such as urinary incontinence that may be a result of impingement of sacral roots. Back pain, a symptom in nearly all patients with lumbar stenosis,5 may be present with or without claudication, particularly in the earlier stages of the disorder.

Physical Examination

Physical examination of patients with suspected lumbar stenosis should begin with examination of the back. The curvature of the spine should be noted, and the mobility and flexibility of the spine with any changes in neurologic symptoms during active flexion or extension should be recorded (particularly the presence of leg pain, paresthesias or numbness with extension of the spine). The skin should be inspected for the presence of any cutaneous signs of occult spinal dysraphisms. Occult spinal dysraphisms, or occult spina bifida, are failures in the complete closure of the neural (vertebral) arches, which often have external signs indicating their presence. These signs may include patches of hair, nevi, hemangiomas or dimples on the lower back in the midline. These conditions are rare in the adult population, however.

The straight leg raising test (Lasègue's sign), which is performed by raising the straight lower extremity and dorsiflexing the foot, is classically associated with reproduction of ipsilateral radicular pain secondary to nerve root compression by a herniated lumbar disc, presumably by stretching the compressed ipsilateral nerve root. Most patients with a true positive straight leg raising sign complain of excruciating sciatica-like pain in the elevated leg at 30 to 40 degrees of elevation. This sign is usually absent in patients with lumbar stenosis.

It should be noted that herniation of disc material and subsequent reparative processes may contribute to the overall picture of stenosis, but acute disc herniations generally produce a clinical picture that differs from the more chronic symptoms of canal stenosis. Patrick's sign, which reproduces leg pain with lateral rotation of the flexed knee, implies ipsilateral degenerative hip joint disease. This is an important piece of the differential diagnosis in patients with stenosis, some of whom may have both conditions.

Neurologic Examination

The neurologic examination in patients with idiopathic degenerative lumbar stenosis may not reveal significant sensorimotor deficits at rest or in a neutral position. Deep tendon reflexes may be decreased, absent or normal, depending on the chronicity of the caudal root compression. Upper motor neuron signs, such as hyperactive deep tendon reflexes or the presence of pathologic reflexes, such as the Babinski's sign or Hoffmann's sign, are typically absent unless there is injury to descending long tracts. With the onset of walking, sensory deficits may appear, and motor weakness or reflex changes may be elicited. Therefore, it is extremely important to perform a thorough neurologic examination before and immediately after symptoms appear following a short period of ambulation. Similarly, changes in the neurologic examination with variations in posture should also be recorded.

Neurogenic vs. Vascular Claudication

The signs and symptoms of neurogenic intermittent claudication should be differentiated from the leg claudication produced by atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the iliofemoral vessels (vascular claudication). Vascular disease is commonly associated with other problems such as impotence in men, dystrophic skin changes (nail atrophy, alopecia), foot pallor or cyanosis, decreased or absent peripheral pulses and arterial bruits. Pain or cramping in the buttocks associated with ambulation is often reported.

Patients with vascular claudication also obtain relief with rest and can very accurately quantitate the distance that they can ambulate before symptoms reappear. However, in contrast to claudication that is due to cauda equina compression, vaso-occlusive leg claudication usually does not occur with changes in posture, and patients typically obtain relief from the leg pain by simply resting the legs even while in the upright position (Table 1).

| Clinical characteristics | Neurogenic claudication | Vascular claudication |

|---|---|---|

| Location of pain | Thighs, calves, back and, rarely, buttocks | Buttocks or calves |

| Quality of pain | Burning, cramping | Cramping |

| Aggravating factors | Erect posture, ambulation, extension of the spine | Any leg exercise |

| Relieving factors | Squatting, bending forward, sitting | Rest |

| Leg pulses and blood pressure | Usually normal | Blood pressure decreased; pulses decreased or absent; bruits or murmurs may be present |

| Skin/trophic changes | Usually absent | Often present (pallor, cyanosis, nail dystrophy) |

| Autonomic changes | Bladder incontinence (rare) | Impotence may coexist with other symptoms of vascular claudication |

Examination of the femoral, popliteal and pedal pulses, as well as inspection of the legs and feet for trophic changes, is essential in order to differentiate vascular from neurogenic claudication. Ankle/brachial indexes and bedside Doppler examinations should be performed if any abnormality in the pulses is discovered or if vascular disease is suspected. Significant symptomatic pelvofemoral atherosclerosis and lumbar stenosis occasionally coexist in the same patient, and noninvasive circulation studies or arteriography may be required to rule out vasculopathy.

Imaging/Diagnostic Studies

The diagnosis of lumbar stenosis depends largely on the clinical history and physical examination. Radiographic confirmation of the diagnosis can be accomplished using various imaging modalities. Plain films of the spine by themselves are not diagnostic but may demonstrate degenerative changes in the vertebrae or disc spaces, disclose some forms of occult spina bifida or reveal spondylolisthesis or scoliosis in some patients. The most commonly involved levels are L3 through L5, although clinically significant stenosis can exist at any or all lumbar levels in a given patient. In the past, lumbar myelography was the usual method for establishing a diagnosis, but it is usually not necessary today. Modern neuroimaging techniques such as computed tomographic (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have facilitated the diagnosis in recent years.

Computed Tomography

CT scans with or without intrathecal contrast injection define the bony anatomy in one or two planes, are able to demonstrate the lumbar subarachnoid space well, may demonstrate encroachment of the canal by hypertrophied lamina, osteophytes, facets or pedicles, and can provide excellent visualization of the vertebral canal so that measurements of the canal diameter can be made with improved accuracy and resolution compared with plain myelograms. Three-dimensional reconstructions using CT also demonstrate the anatomy of the vertebral canal.

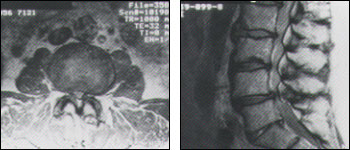

Hypertrophy of the lamina, pedicles and apophyseal joints, along with a thickened ligamentum flavum, impinge on the posterolateral aspects of the lumbar canal, giving it the classic “cloverleaf” or “trefoil” appearance on axial CT scans (Figure 2). Although the trefoil canal is considered to be virtually pathognomonic for lumbar stenosis, a normal trefoil variant is occasionally encountered in an otherwise completely asymptomatic patient.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

CT scans with intrathecal contrast injection are able to demonstrate the lumbar subarachnoid space and nerve roots with enhanced sensitivity, but this is an invasive test with potential morbidity. For this reason, MRI scanning, with its multiplanar imaging capability, is currently the preferred modality for establishing a diagnosis and excluding other conditions. MRI depicts soft tissues, including the cauda equina, spinal cord, ligaments, epidural fat, subarachnoid space and intervertebral discs, with exquisite detail in most instances. Loss of epidural fat on T1-weighted images, loss of cerebrospinal fluid signal around the dural sac on T2-weighted images and degenerative disc disease are common features of lumbar stenosis on MRI (Figures 4a and 4b).

Electromyelography

Electromyelograms with nerve conduction velocity studies may assist in confirming the multiradicular involvement of cauda equina compression. Electromyelography and nerve conduction velocity may also be helpful in diagnosing demyelinating or inflammatory neuropathies and can be of great benefit in distinguishing vascular from neurogenic claudication in situations where the clinical and radiographic pictures are equivocal. Ultimately, however, imaging studies are essential in the diagnosis of lumbar stenosis and, in most cases, electromyelography and nerve conduction velocity studies will not be required.

Differential Diagnosis

As mentioned previously, compression of the lumbar root may have many causes. However, few conditions produce the typical clinical picture of neurogenic claudication that occurs in lumbar stenosis. Table 2 lists potential causes of cauda equina compression that should be ruled out by appropriate diagnostic studies before a diagnosis of lumbar stenosis is made.

| Conus medullaris and cauda equina neoplasms, and benign cystic lesions (neurofibromas, ependymomas, hemangioblastomas, dermoids, epidermoids, lipomas) |

| Neural compression from metastatic disease to bone (lung, breast, myeloma, lymphoma) |

| Centrally herniated discs |

| Degenerative spondylolisthesis |

| Trauma/fractures |

| Epidural abscess |

| Inflammatory arachnoiditis |

Cauda equina syndromes usually occur as a result of compression of the nerve roots in the lumbosacral spine distal to the conus medullaris. Since the root supply to the lower extremities and genitoperineal regions travels in very close apposition within the thecal sac, external compression such as that occurring with lumbar canal stenosis is manifested by dysfunction in multiple root distributions. For example, pain and other sensory deficits may occur in several lumbar and/or sacral dermatomal territories, as well as weakness in the various muscle groups supplied by these nerve roots.

Cauda equina syndromes also may occur secondary to neoplasms, trauma, and inflammatory or infectious processes. An important reason to obtain MRI scans (as opposed to CT scans) in patients with neurogenic claudication is that MRI aids in the exclusion of more serious conditions, such as tumors of the conus medullaris or cauda equina,9 or infectious processes.

It is rare for patients with tumors of the lumbosacral spine to present exclusively with symptoms suggestive of neurogenic intermittent claudication. In contrast to the back and leg pain associated with degenerative lumbar stenosis, the pain associated with a lumbosacral spinal tumor typically worsens with recumbency, awakens the patient at night and is relieved with walking.8

Lumbar epidural abscesses usually are associated with rapidly evolving neurologic deficits, severe back pain and other clinical manifestations that facilitate the diagnosis. These patients may or may not present with fever but almost always demonstrate back pain and exquisite tenderness to palpation localized to the levels of suppuration.

Pathologic, traumatic or osteoporotic compression fractures of lumbar vertebrae also may present with symptoms of cauda equina impingement. Healing of clinically silent fractures may produce exuberant growth of bone, which may lead to canal stenosis and root impingement. Therefore, a search for a history of treated malignancies, evidence of concurrent malignancies or a history of falls or trauma to the spine may be important to the diagnosis.

Degenerative subluxation of lumbar vertebrae (spondylolisthesis) is another cause of acquired stenosis of the lumbar spinal canal, particularly at the L4 and L5 levels, and may manifest clinically with neurogenic intermittent claudication as well.5 Lumbar stenosis sometimes occurs following posterior lumbar fusions, possibly as a result of reactive bony hypertrophy at or adjacent to the fused segments.

Treatment

Since most patients who develop lumbar stenosis are middle-aged or elderly, it is important to ascertain their relative surgical risks. Although decompressive lumbar laminectomy can be an extensive procedure, most patients, even the elderly, are medically capable of tolerating the procedure. In general, these patients are severely disabled by their symptoms and are usually willing to accept a small degree of risk to obtain relief. Anticoagulation therapy or severe cardiac or respiratory disease may be contraindications to surgery.

Risks and Complications of Decompressive Surgery

The risks of laminectomy depend on the number of levels to be decompressed, concomitant medical problems, difficult anatomy as a result of scarring from previous operations or a markedly stenotic canal that may require extensive bone removal and dissection, as well as the overall risks imposed by general anesthesia. Potential complications of the standard decompressive laminectomy include wound infection, hematoma formation, dural tears with subsequent cerebrospinal fluid leaks and risk of meningitis, nerve root damage and the potential for creating postoperative spinal instability. Surgical blood loss is generally well tolerated, but transfusion may be required. The overall surgical mortality associated with decompressive laminectomy is approximately 1 percent.10

The standard decompressive lumbar laminectomy involves a midline incision over the involved levels, dissection down to the spinous processes and progressive removal or “unroofing” of the posterior elements of the lumbar canal (spinous processes, laminae and pedicles), as well as removal of thickened ligamenta flava.

Typically, multilevel decompressive laminectomies are performed since canal stenosis commonly occurs over several levels. Rarely is excision of herniated intervertebral discs required. Removal of the medial portions of the articular facets is often performed, particularly if there is evidence of osteophyte formation. This maneuver has the potential of creating instability at the levels undergoing surgery if the bone resection is extended too far laterally, particularly if bilateral facetectomies are performed.

An alternative technique7 spares the articular facets on one side and creates a unilateral decompressive hemilaminectomy while undercutting the contralateral lamina, removing the ligamentum flavum and performing unilateral bony fusion as well. Another type of decompressive procedure that has been described with good postoperative success is multilevel laminotomy, whereby “windows” or fenestrations are created by removing the superior aspect of the inferior lamina and the inferior aspect of the superior lamina at involved levels. Proponents of this approach believe that sparing the interspinous ligaments and preserving spinous processes minimizes the risk of postoperative instability.

Recently, increasing attention has been paid to lateral recess stenosis syndrome as a cause of back pain and claudication. The lateral recess is the space within the spinal canal adjacent to the exit zone of the nerve roots.

Some authors believe that, in select circumstances, medial facetectomies, foraminotomies and decompression of the lateral recesses are sufficient to relieve the symptoms of neurogenic claudication.11 Other procedures, such as expansile laminoplasty, which involves the en-bloc removal and loose reattachment of the posterior vertebral arches, have not been studied extensively. Overall, these various procedures have met with mixed results, although some patients will undoubtedly benefit from less extensive decompressive procedures depending on the morphology and anatomic location of their nerve root impingement. Regardless of the surgical approach that is chosen, if decompression is not adequate, relief of symptoms may be incomplete or the problem may recur following a short period of clinical improvement.

Results of Surgical Treatment

Most patients benefit from wide decompression of the lumbar canal. Some reports place the percentage of patients benefiting from surgery at 95 percent, with greater than 90 percent of patients returning to their previous activity levels, regardless of age.12 However, recent reports2,12 dismiss these figures as optimistic, instead claiming long-term neurologic improvement in approximately 65 percent of patients. It is fairly clear, however, that in most patients with clear radiographic and clinical evidence of stenosis, decompressive surgery provides significant relief.

In a recent analysis, comorbid conditions and psychologic factors were found to play a significant role in patients' individual perceptions of outcome following either laminectomy or laminotomy. Patients with significant comorbid illnesses reported less relief of pain and less functional recovery than expected following decompression.13 In patients with chronic, severe symptoms, decompression of the neural elements may not result in immediate pain resolution, nor are longstanding preoperative motor deficits likely to resolve immediately. Nonetheless, following cauda equina decompression, the relentless progression of neurologic dysfunction may be slowed or halted.

Nonsurgical Treatment for Lumbar Stenosis

Conservative treatment for lumbar stenosis, such as lumbar bracing, bed rest, physical therapy and pain management, has few proven benefits in the long term. Unless debilitating medical conditions prohibit surgery under general anesthesia, medical or nonsurgical management of lumbar stenosis is not a practical option if symptoms are incapacitating. Nonsurgical management of this condition may be attempted initially in patients with mild symptoms of short duration.

Morbidly obese patients with symptoms of neurogenic claudication may improve following institution of a weight loss program. Back strengthening exercises, strict physical therapy regimens and symptomatic management with nonsteroidal analgesics also may benefit some patients initially but, in contrast to patients with herniated intervertebral discs (who often respond favorably to nonsurgical management), patients with lumbar stenosis often show no improvement on long-term follow-up. Their symptoms rapidly return with the resumption of activity. Since many of these persons are severely limited by pain, early surgery is the best way to return them to full activity and independent living.