This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(7):2077-2088

Acute renal failure occurs in 5 percent of hospitalized patients. Etiologically, this common condition can be categorized as prerenal, intrinsic or postrenal. Most patients have pre-renal acute renal failure or acute tubular necrosis (a type of intrinsic acute renal failure that is usually caused by ischemia or toxins). Using a systematic approach, physicians can determine the cause of acute renal failure in most patients. This approach includes a thorough history and physical examination, blood tests, urine studies and a renal ultrasound examination. In certain situations, such as when a patient has glomerular disease, microvascular disease or obstructive disease, rapid diagnosis and treatment are necessary to prevent permanent renal damage. By maintaining euvolemia, recognizing patients who are at increased risk and minimizing exposure to nephrotoxins, physicians can decrease the incidence of acute renal failure. Once acute renal failure develops, supportive therapy is critical to maintain fluid and electrolyte balances, minimize nitrogenous waste production and sustain nutrition. Death is most often caused by infection or cardiorespiratory complications.

Over the past 40 years, the survival rate for acute renal failure has not improved, primarily because affected patients are now older and have more comorbid conditions.3–5 Infection accounts for 75 percent of deaths in patients with acute renal failure, and cardiorespiratory complications are the second most common cause of death.2,4 Depending on the severity of renal failure, the mortality rate can range from 7 percent to as high as 80 percent.3,5

In acute renal failure, the glomerular filtration rate decreases over days to weeks. As a result, excretion of nitrogenous waste is reduced, and fluid and electrolyte balances cannot be maintained. Patients with acute renal failure are often asymptomatic, and the condition is diagnosed by observed elevations of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and serum creatinine levels. Most authorities define the condition as an acute increase of the serum creatinine level from baseline (i.e., an increase of at least 0.5 mg per dL [44.2 μmol per L]).3 Complete renal shutdown is present when the serum creatinine level rises by at least 0.5 mg per dL per day and the urine output is less than 400 mL per day (oliguria).

Not all BUN and serum creatinine elevations result from acute renal failure. Cephalosporins and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra) may cause acute renal failure as a result of interstitial disease, but these agents sometimes cause elevated serum creatinine levels simply by inhibiting the tubular secretion of creatinine without causing real damage to the kidneys. The BUN can be elevated in patients who are receiving corticosteroids, those with increased catabolism or those with gastrointestinal tract bleeding.

Diagnostic Strategy and Differential

Acute renal failure can be divided into three categories. Prerenal acute renal failure is characterized by diminished renal blood flow (60 to 70 percent of cases). In intrinsic acute renal failure, there is damage to the renal parenchyma (25 to 40 percent of cases). Postrenal acute renal failure occurs because of urinary tract obstruction (5 to 10 percent of cases).2 The most commonly encountered diagnoses are prerenal acute renal failure and acute tubular necrosis (a type of intrinsic acute renal failure).

Using a step-by-step approach, physicians can determine the cause of acute renal failure in most patients (Figure 1). According to one investigative team, “The time honored approach to evaluating a patient with [acute renal failure] is to exclude prerenal and postrenal causes and then, if necessary, initiate an examination to determine potential renal [intrinsic] etiologies.”1

The first step is to obtain a thorough history and perform a complete physical examination. Key symptoms and physical findings for acute renal failure and uremia are listed in Table 1. Probable etiologies based on the findings of the history and physical examination are provided in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

| Symptoms |

| Anorexia |

| Fatigue |

| Mental status changes |

| Nausea and vomiting |

| Pruritus |

| Seizures (if blood urea nitrogen level is very high) |

| Shortness of breath (if volume overload is present) |

| Physical findings |

| Asterixis and myoclonus |

| Pericardial or pleural rub |

| Peripheral edema (if volume overload is present) |

| Pulmonary rales (if volume overload is present) |

| Elevated right atrial pressure (if volume overload is present) |

| History | Probable causes of acute renal failure | |

|---|---|---|

| Review of systems | ||

| Pulmonary system | ||

| Sinus, upper respiratory or pulmonary symptoms | Pulmonary-renal syndrome or vasculitis | |

| Cardiac system | ||

| Symptoms of heart failure | Decreased renal perfusion | |

| Intravenous drug abuse, prosthetic valve or valvular disease | Endocarditis | |

| Gastrointestinal system | ||

| Diarrhea, vomiting or poor intake | Hypovolemia | |

| Colicky abdominal pain radiating from flank to groin | Urolithiasis | |

| Genitourinary system | ||

| Symptoms of benign prostatic hypertrophy | Obstruction | |

| Musculoskeletal system | ||

| Bone pain in the elderly | Multiple myeloma or prostate cancer | |

| Trauma or prolonged immobilization | Rhabdomyolysis (pigment nephropathy) | |

| Skin | ||

| Rash | Allergic interstitial nephritis, vasculitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, atheroemboli or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | |

| Constitutional symptoms | ||

| Fever, weight loss, fatigue or anorexia | Malignancy or vasculitis | |

| Past medical history | ||

| Multiple sclerosis, diabetes mellitus or stroke | Neurogenic bladder | |

| Past surgical history | ||

| Recent surgery or procedure | Ischemia, atheroemboli, endocarditis or exposure to contrast agent | |

| Medication history | ||

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics or acyclovir (Zovirax) | Decreased renal perfusion, acute tubular necrosis or allergic interstitial nephritis | |

| Physical examination | Probable causes of acute renal failure | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Vital signs | |||

| Temperature | Possible infection | ||

| Blood pressure | Hypertension: nephrotic syndrome or malignant hypertension | ||

| Hypotension: volume depletion or sepsis | |||

| Weight loss or gain | Hypovolemia or hypervolemia | ||

| Mouth | Dehydration | ||

| Jugular veins and axillae (perspiration) | Hypovolemia or hypervolemia | ||

| Pulmonary system | Signs of congestive heart failure | ||

| Heart | New murmur of endocarditis or signs of congestive heart failure | ||

| Abdomen | Bladder distention suggesting urethral obstruction | ||

| Pelvis | Pelvic mass | ||

| Rectum | Prostate enlargement | ||

| Skin | Rash of interstitial nephritis, purpura of microvascular disease, livedo reticularis suggestive of atheroembolic disease, or splinter hemorrhages or Osler's nodes of endocarditis | ||

Blood and urine tests can provide supporting data. BUN and serum electrolyte, creatinine, calcium, phosphorus and albumin levels, as well as a complete blood count with differential, should be obtained in all patients. In certain circumstances, other blood tests are indicated (Table 4). All patients should have the following urine studies: dipstick test, microscopy, sodium and creatinine levels, and urine osmolality determination.

| Findings on blood tests | Diagnoses to consider |

|---|---|

| Elevated uric acid level | Suggestive of malignancy or tumor lysis syndrome leading to uric acid crystals; also seen in prerenal acute renal failure |

| Elevated creatine kinase or myoglobin levels | Rhabdomyolysis |

| Elevated prostate-specific antigen | Prostate cancer |

| Abnormal serum protein electrophoresis | Multiple myeloma |

| Low complement levels | Systemic lupus erythematosus, postinfectious glomerulonephritis, subacute bacterial endocarditis |

| Positive antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody | Small-vessel vasculitis (Wegener's granulomatosis or polyarteritis nodosa) |

| Positive antinuclear antibody or antibody to double-stranded DNA | Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Positive antibody to glomerular basement membrane | Goodpasture's syndrome |

| Positive antibodies to streptolysin O, streptokinase or hyaluronidase | Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis |

| Schistocytes on peripheral smear, decreased haptoglobin level, elevated lactate dehydrogenase level or elevated serum bilirubin level | Hemolytic uremic syndrome or thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Low albumin level | Liver disease or nephrotic syndrome |

On occasion, renal biopsy is necessary to establish the diagnosis, determine the prognosis or guide therapy. Only a small subset of patients have indications for biopsy.6 Most often, biopsy is performed when a patient has intrinsic acute renal failure that is not acute tubular necrosis. The main complications of biopsy are bleeding, arteriovenous fistula and death, but the rate of serious complications is less than 1 percent.3

| Types of acute renal failure and underlying problem | Possible disorders |

|---|---|

| Prerenal acute renal failure | |

| True intravascular depletion | Sepsis, hemorrhage, overdiuresis, poor fluid intake, vomiting, diarrhea |

| Decreased effective circulating volume to the kidneys | Congestive heart failure, cirrhosis or hepatorenal syndrome, nephrotic syndrome |

| Impaired renal blood flow because of exogenous agents | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Intrinsic acute renal failure | |

| Acute tubular necrosis | Ischemia |

| Toxins: drugs (e.g., aminoglycosides), contrast agents, pigments (myoglobin or hemoglobin) | |

| Glomerular disease | Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis: systemic lupus erythematosus, small-vessel vasculitis (Wegener's granulomatosis or polyarteritis nodosa), Henoch-Schönlein purpura (immunoglobulin A nephropathy), Goodpasture's syndrome |

| Acute proliferative glomerulonephritis: endocarditis, poststreptococcal infection, postpneumococcal infection | |

| Vascular disease | Microvascular disease: atheroembolic disease (cholesterol-plaque microembolism), thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome, HELLP syndrome or postpartum acute renal failure |

| Macrovascular disease: renal artery occlusion, severe abdominal aortic disease (aneurysm) | |

| Interstitial disease | Allergic reaction to drugs, autoimmune disease: (systemic lupus erythematosus or mixed connective tissue disease), pyelonephritis, infiltrative disease (lymphoma or leukemia) |

| Postrenal acute renal failure | Benign prostatic hypertrophy or prostate cancer, cervical cancer, retroperitoneal disorders, intratubular obstruction (crystals or myeloma light chains), pelvic mass or invasive pelvic malignancy, intraluminal bladder mass (clot, tumor or fungus ball), neurogenic bladder, urethral strictures |

Prerenal Acute Renal Failure

In prerenal acute renal failure, the problem is impaired renal blood flow as a result of true intravascular depletion, decreased effective circulating volume to the kidneys or agents that impair renal blood flow.

| Type of renal failure | BUN-to-creatinine ratio | Urine osmolality | Fractional excretionof sodium* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prerenal acute renal failure | > 20:1 | > 500 mOsm | < 1% |

| Intrinsic acute renal failure | < 20:1 | 250 to 300 mOsm | > 3% |

The fractional excretion of sodium should be determined. The fraction of filtered sodium that is ultimately excreted is equal to 100 × (urine sodium/serum sodium) ÷ (urine creatinine/serum creatinine). This value is less than 1 percent in most patients with prerenal acute renal failure.

In patients with prerenal acute renal failure, the parenchyma is undamaged, and the kidneys respond as if volume depletion has occurred. Thus, the kidneys avidly reabsorb sodium in order to reabsorb water.

Specific causes of a fractional excretion of sodium of less than 1 percent that are not the result of prerenal acute renal failure include contrast nephropathy and pigment nephropathy.

Two instances of prerenal acute renal failure with a fractional excretion of sodium greater than 1 percent deserve mention. First, patients receiving diuretics may truly have prerenal acute renal failure, but the fractional excretion of sodium may be increased by diuretic-induced sodium excretion. Second, patients with chronic renal insufficiency have impaired sodium reabsorption. Therefore, if they develop prerenal acute renal failure, they may be unable to reabsorb enough sodium to have a less than 1 percent fractional excretion of sodium.

Acute renal failure in patients with congestive heart failure occurs because of decreased renal blood flow. This decrease is due to hypovolemia from overdiuresis or hypervolemia that causes elevated filling pressures of the left ventricle and leads to decreased cardiac output. Patients in the former group may respond to the discontinuation of diuretics and gentle hydration. Patients in the latter group are treated with diuretics and may need inotropes and vasodilators. Invasive hemodynamic monitoring may be required for fluid management.

The primary agents that cause prerenal acute renal failure are angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The inhibition of ACE prevents the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, leading to decreased levels of angiotensin II. Angiotensin II increases the glomerular filtration rate by causing constriction of the efferent arteriole; its absence decreases the glomerular filtration rate because of dilatation of the efferent arteriole. In certain patients (e.g., those with hypovolemia or bilateral renal artery stenosis), the glomerular filtration rate is particularly dependent on the effects of angiotensin II. If these patients take an ACE inhibitor, their glomerular filtration rate decreases, and pre-renal acute renal failure can develop. Potassium, BUN and creatinine levels should be obtained soon after patients start taking an ACE inhibitor. NSAIDs cause prerenal acute renal failure by blocking prostaglandin production, which also alters local glomerular arteriolar perfusion.

Diminished renal blood flow causes ischemia in the renal parenchyma. If the ischemia is prolonged, acute tubular necrosis may develop. Early restoration of renal blood flow should shorten the ischemic time and prevent parenchymal injury. A response to the restoration of renal blood flow should occur in 24 to 48 hours. The keys to therapy are treating the underlying disorder, maintaining euvolemia and eliminating offending agents.

Intrinsic Acute Renal Failure

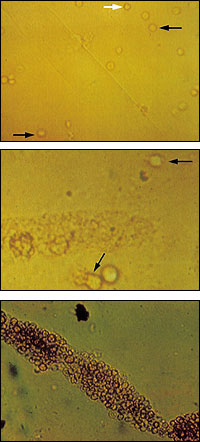

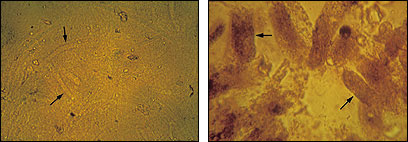

Intrinsic acute renal failure is subdivided into four categories: tubular disease, glomerular disease, vascular disease and interstitial disease. In intrinsic acute renal failure, the renal parenchyma is injured. The damage to tubule cells leads to certain urine microscopic findings (Table 63 and Figures 2 and 3). Parenchymal injury causes impaired sodium reabsorption and results in a fractional excretion of sodium of greater than 3 percent and an isotonic urine osmolality of 250 to 300 mOsm (Table 7).

TUBULAR DISEASE

Acute tubular necrosis is the most common cause of intrinsic acute renal failure in hospitalized patients. This condition is usually induced by ischemia or toxins.

In ischemic acute tubular necrosis, unlike prerenal acute renal failure, the glomerular filtration rate does not improve with the restoration of renal blood flow. Ischemic acute tubular necrosis is frequently reversible, but if the ischemia is severe enough to cause cortical necrosis, irreversible renal failure can occur.2,3

Contrast agents and aminoglycosides are the agents most often associated with acute tubular necrosis. The condition can also be caused by pigment from myoglobinuria (rhabdomyolysis) or hemoglobinuria (hemolysis).

Acute tubular necrosis has three phases.2 Renal injury evolves during the initiation phase, which lasts hours to days. In the maintenance phase, which lasts days to weeks, the glomerular filtration rate reaches its nadir and urine output is at its lowest. The recovery phase lasts days, often beginning with post-acute tubular necrosis diuresis. Hypovolemia from excess urine output is a concern during this phase. Despite recovery of urine production, patients can still have difficulty with uremia and homeostasis of electrolytes and acid because tubular function is not completely recovered. Diligent monitoring is indicated throughout all phases of acute tubular necrosis.

Patients at risk for acute tubular necrosis include those with diabetes, congestive heart failure or chronic renal insufficiency. Acute tubular necrosis may be prevented by promptly treating patients with reversible causes of ischemic or prerenal acute renal failure and by maintaining appropriate hydration in patients who are receiving nephrotoxins.

Once acute tubular necrosis develops, therapy is supportive. Drugs such as mannitol, loop diuretics, dopamine and calcium channel blockers have been somewhat successful in promoting diuresis in animals, but similar results have not been obtained in humans.7

GLOMERULAR DISEASE

Glomerulonephritis is characterized by hypertension, proteinuria and hematuria.6 Of the many types of glomerulonephritis, most are associated with chronic renal disease. In general, the two types of glomerulonephritis that cause acute renal failure are rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and acute proliferative glomerulonephritis. The latter type occurs in patients with bacterial endocarditis or other postinfectious conditions.

Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis can be a primary disorder, or it can occur secondary to systemic disease (Table 5). Once this condition is suspected, treatable systemic disease must be sought through serologic markers or renal biopsy. Renal function can decline quickly in patients with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis, and end-stage renal disease can develop in days to weeks.8

Patients with rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis are treated with glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan). Plasma exchange is believed to benefit patients with Goodpasture's syndrome but has not been of proven benefit in patients with other types of glomerulonephritis.8

The underlying condition should be treated in patients with acute proliferative glomerulonephritis.

VASCULAR DISEASE

Microvascular or macrovascular disease (major renal artery occlusion or severe abdominal aortic disease) can cause acute renal failure.

The classic microvascular diseases often present with microangiopathic hemolysis and acute renal failure occurring because of glomerular capillary thrombosis or occlusion, often with accompanying thrombocytopenia. Typical examples of these diseases are thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome and HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated l iver enzymes and l ow platelets).

The classic pentad in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura includes fever, neurologic changes, renal failure, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia. Hemolytic uremic syndrome is similar to thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura but does not present with neurologic changes. HELLP syndrome is a type of hemolytic uremic syndrome that occurs in pregnant women with the addition of transaminase elevations.

The microvascular diseases that cause acute renal failure are often treated with plasmapheresis and sometimes with corticosteroids.9–11 An increasing platelet count is a marker of improvement. In patients with parturition-related acute renal failure (HELLP syndrome), expedition of delivery is the initial treatment of choice.

Atheroembolic disease is another important cause of irreversible acute renal failure. Patients with atherosclerotic disease who undergo an invasive procedure (e.g., vascular surgery or interventional vascular studies) or have an acute arrhythmia are at increased risk for acute renal failure induced by atheroemboli. Acute renal failure from embolic disease may present one day to seven weeks after the inciting event.12

Atheroembolism is relatively common in tertiary care and intensive care units, presenting classically with “purple toes and renal failure.” Evidence of microembolism may be present in other organs (livedo reticularis, gastrointestinal tract bleeding, pancreatitis, persisting encephalopathy and retinal embolism seen as “Hollenhorst” plaques). The diagnosis of atheroembolic disease can be confirmed on skin or renal biopsy. Treatment is nonspecific, but avoiding further vascular intervention and anticoagulation is strongly recommended.13

INTERSTITIAL DISEASE

Acute interstitial nephritis usually presents with fever, rash and eosinophilia. Urine staining that is positive for eosinophils is suggestive of this condition. Acute interstitial nephritis is usually the result of an allergic reaction to a drug, but it may also be caused by autoimmune disease, infection or infiltrative disease.3

Many drugs can cause acute interstitial nephritis, but the more common ones are NSAIDs, penicillins, cephalosporins, sulfonamides, diuretics and allopurinol (Zyloprim). Renal function should improve after the offending agent is withdrawn. Corticosteroids are sometimes helpful in speeding recovery.2

Postrenal Acute Renal Failure

Postrenal acute renal failure can only occur if both urinary outflow tracts are obstructed or the outflow tract of a solitary kidney is obstructed. The condition is most often due to obstruction of the lower urinary tract.

| Obstruction (vast majority of patients with anuria) |

| Bilateral renal cortical necrosis |

| Fulminant glomerulonephritis (usually some type of rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis) |

| Acute bilateral renal artery or vein occlusion (rare) |

The primary causes of postrenal acute renal failure include prostatic hypertrophy, prostate cancer, cervical cancer and retroperitoneal disorders. Intratubular causes include crystals (e.g., urate) and myeloma light chains.3

One of the first evaluation steps in most patients with acute renal failure is to determine whether a patient has postrenal acute renal failure, because treatment is frequently relatively easy and the potential for recovery of renal function is often inversely related to the duration of obstruction.3 Bladder catheterization may be diagnostic and therapeutic in patients with bladder or urethral obstruction.

Hydronephrosis detected on renal ultrasound examination is the major signal that obstruction is present. For the detection of obstruction, ultrasonography has a sensitivity of 90 percent and a specificity that approaches 100 percent.14 False-negative ultrasound examinations can occur if the obstruction is very early or retroperitoneal fibrosis is present.

In patients with postrenal acute renal failure, treatment efforts are directed at the underlying disease. Treatments available for various causes include bladder catheterization, percutaneous nephrostomy, lithotripsy, ureteral stenting and urethral stenting.

General Treatment of Acute Renal Failure

Initial treatment should focus on correcting fluid and electrolyte balances and uremia while the cause of acute renal failure is being sought. A volume-depleted patient is resuscitated with saline. More often, however, volume overload is present, especially if patients are oliguric or anuric.

Furosemide (Lasix) administered intravenously every six hours is the initial treatment for volume overload. Depending on whether the patient takes furosemide regularly, the initial dose can be between 20 and 100 mg. If an inadequate response occurs in one hour, the dose is doubled. This process is repeated until adequate urine output is achieved. A continuous furosemide drip may be required. The last resort is ultrafiltration via dialysis.

The main electrolyte disturbances in the acute setting are hyperkalemia and acidosis. The aggressiveness of treatment depends on the degree of hyperkalemia and the changes seen on the electrocardiogram. Intravenously administered calcium (10 mL of a 10 percent solution of calcium gluconate) is cardioprotective and temporarily reverses the neuromuscular effects of hyperkalemia.

Potassium can be temporarily shifted into the intracellular compartment using intravenously administered insulin (10 units) and glucose (25 g), inhaled beta agonists or intravenously administered sodium bicarbonate (three ampules in 1 L of 5 percent dextrose).15 Potassium excretion is achieved with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) and/or diuretics. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate is given orally (25 to 50 g mixed with 100 mL of 20 percent sorbitol) or as an enema (50 g in 50 mL of 70 percent sorbitol and 150 mL of tap water).15 If these measures do not control the potassium level, dialysis should be initiated.

Acidosis is treated with intravenously or orally administered sodium bicarbonate if the serum bicarbonate level is less than 15 mEq per L (15 mmol per L) or the pH is less than 7.2. The amount of supplemental bicarbonate needed is determined on the basis of the bicarbonate deficit equation: bicarbonate deficit (mEq per L) = 0.5 × weight (kg) × (24 – actual serum bicarbonate level).

Sodium bicarbonate ampules are available in two concentrations: 44.6 and 50 mEq per 50 mL. Patients can also be treated orally with sodium bicarbonate tablets (a 300-mg tablet contains 3.6 mEq of sodium bicarbonate), Shohl's solution in 30-mL doses (1 mEq of sodium bicarbonate per mL) or powdered sodium bicarbonate (Arm and Hammer baking soda provides approximately 50 mEq of sodium bicarbonate per rounded teaspoon). Serum bicarbonate levels and pH should be followed closely. Intractable acidosis requires dialysis.

Because acute renal failure is a catabolic state, patients can become nutritionally deficient. Total caloric intake should be 30 to 45 kcal (126 to 189 kJ) per kg per day, most of which should come from a combination of carbohydrates and lipids. In patients who are not receiving dialysis, protein intake should be restricted to 0.6 g per kg per day. Patients who are receiving dialysis should have a protein intake of 1 to 1.5 g per kg per day.16

Finally, all medications should be reviewed, and their dosages should be adjusted based on the glomerular filtration rate and the serum levels of medications.

Between 20 and 60 percent of patients require short-term dialysis, particularly when the BUN exceeds 100 mg per dL (35.7 mmol per L of urea) and the serum creatinine level exceeds the range of 5 to 10 mg per dL (442 to 884 μmol per L). Indications for dialysis include acidosis or electrolyte disturbances that do not respond to pharmacologic therapy, fluid overload that does not respond to diuretics, and uremia. In patients with progressive acute renal failure, urgent consultation with a nephrologist is indicated.