Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(10):3065-3072

See related patient information handout on respiratory infections during pregnancy, written by the authors of this article.

Prenatal patients are often exposed to respiratory viruses at home and at work. Understandably, these patients may be concerned and want immediate answers and advice from their physicians. While most women who are exposed to chickenpox are immune, serologic testing can be performed and susceptible patients can be treated with varicella-zoster immune globulin. If the prenatal patient is infected with the varicella-zoster virus, the risk of fetal manifestations is less than 2 percent. Women who have been exposed to fifth disease can undergo serologic testing to determine the likelihood of infection. If the prenatal patient becomes infected with fifth disease during the first 20 weeks of gestation, the risk of fetal manifestations is about 9 percent and includes nonimmune hydrops and death. Cytomegalovirus, which is the most common congenital infection, is generally asymptomatic in the mother. Infected fetuses have a 25 percent chance of developing early or late neurologic manifestations. The evidence of harm from other common respiratory viruses is inconsistent.

Pregnant women are often exposed to respiratory viruses. Occasionally, the fetus may be harmed by the virus. Physicians may be contacted by understandably anxious prenatal patients who want information and advice. Patients commonly ask the following questions: “What are my chances of becoming infected?” “If I become infected, what are the chances that the baby will be affected?” “What could the infection do to the baby?” and “How can I tell if the baby has been affected?”

The likelihood of infection in the mother depends on her immune status and the nature of the exposure. The risk to the fetus depends on maternal immune status and the gestational age of the fetus (Table 1). While the fetus can become infected at any time during the pregnancy, first-trimester infections are generally more dangerous. Possible outcomes include no harm to the fetus, fetal loss, fetal malformation, preterm delivery, fetal growth restriction or postnatal infection.1 Malformations may include impaired development of specific tissues (e.g., microphthalmia, microcephaly) and inflammatory reactions and scarring (e.g., chorioretinitis, cataracts).2

| Disease | Susceptibility in pregnancy | Incidence in pregnancy | Incubation period (days) | Contagious period | Attack rate | Risk of fetal manifestations if mother infected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chickenpox | 10% | 1/7,500 | 11 to 21 | From 2 days before onset of rash until all lesions have crusted (usually day 5 to 6) | 18% (casual) | 2% in first 20 weeks of gestation |

| 90% (household) | ||||||

| Fifth disease | 50% | < 1/100 | 4 to 14 | 5 to 10 days before onset of the rash and other symptoms | 5% (casual) | 9% in first 20 weeks of gestation |

| 20% (classroom) | ||||||

| 50% (household) | < 1% after 20 weeks of gestation | |||||

| Cytomegalovirus | 2% (lower SES) | 1 to 4% (primary infection) | Unknown | Unknown | 50 to 80% | Primary infection: 4% |

| 50% (middle and upper SES) | Recurrent infection: 0.19% to 1.5% | |||||

| Common cold | High | High | 1 to 3 | First 2 to 3 days of symptoms | 38% (household) | Unknown |

| Influenza | Varies | Varies | 1 to 5 | 24 hours before to 7 days after onset of symptoms | Varies (commonly 10 to 20%) | Unknown |

| Rubella | 20% | Rare | 12 to 23 | Few days before to 7 days after onset of rash | 50 to 60% (household) | 85% before 9 weeks |

| 52% from 9 to 12 weeks | ||||||

| Rare after 16 weeks |

Chickenpox

BACKGROUND

Chickenpox (varicella) is caused by a highly contagious DNA herpesvirus, which is transmitted by respiratory droplets. About 80 percent of women who have no history of chickenpox are found to be immune by serologic testing.3 Maternal herpes zoster does not put the fetus at risk and has no pregnancy-related significance for the mother.3 Occasionally, chickenpox develops in susceptible mothers after exposure to patients with herpes zoster. Among women who are infected with chickenpox, 10 to 30 percent develop varicella pneumonia, which may be more severe in pregnant women and is associated with mortality rates as high as 40 percent.4 Administration of the varicella vaccine is recommended in susceptible women of childbearing age who are not pregnant.5

FETAL AND NEONATAL INFECTION

The primary risk of maternal chickenpox in early pregnancy is fetal infection, which may result in the congenital varicella syndrome. In the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, the risk of embryopathy after maternal varicella infection is less than 2 percent.6–9 Congenital varicella occurs most often during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, but infection late in pregnancy can also result in congenital varicella.10 Congenital varicella syndrome is characterized by limb hypoplasia, cutaneous scarring, chorioretinitis, microphthalmia, Horner's syndrome, cataracts, cortical atrophy, mental retardation, microcephaly and low birth weight.2

If varicella manifests in the mother more than five days before delivery, there is essentially no risk to the neonate, probably because varicella antibodies have transferred to the fetus.11 Immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin A (IgA) are produced two to five days after the initial infection and reach a maximum after two to three weeks. However, maternal varicella infection between five days before and two days after delivery poses a substantial risk to the neonate. Neonatal varicella is a severe infection that manifests with skin lesions and pneumonia and has a mortality rate of up to 31 percent.12,13 In the first 10 days of life, up to 50 percent of these infants will be affected.

POSTEXPOSURE MANAGEMENT

Mothers who may be infected with varicella should not go into the clinic waiting room because other patients may be at risk for infection. Usually, maternal varicella is diagnosed clinically, but infection is confirmed if a fourfold rise in varicella-specific IgG antibodies occurs over a 14- to 21-day period.14

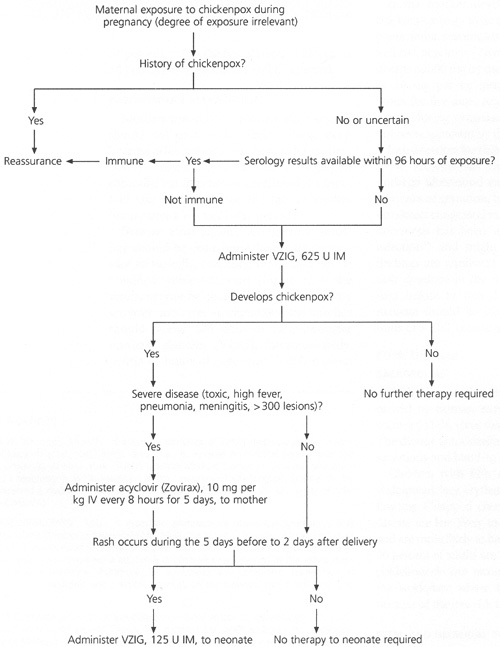

Because most patients are immune, serology should be done immediately after exposure to varicella, assuming the results can be obtained within 96 hours (Figure 1). If the results cannot be obtained this soon or if the serology indicates susceptibility, the mother should receive 625 units of varicella-zoster immune globulin (VZIG), intramuscularly, within 96 hours of exposure.15 VZIG is given to prevent or ameliorate maternal infection; whether it prevents congenital varicella is unknown.

If the mother develops a severe case of chickenpox (e.g., toxic appearance, high fever, pneumonia, meningitis or more than 300 skin lesions), acyclovir (Zovirax) may be given in a dosage of 800 mg by mouth four times per day or 10 mg per kg intravenously every eight hours for five days. Acyclovir is probably safe to use during pregnancy,16,17 although it has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

We recommend that infected mothers undergo ultrasound examinations at 18 and 28 weeks of gestation, but the ultrasound may not detect congenital varicella syndrome. Cordocentesis has been used to diagnose fetal infection18 and might be considered when findings are equivocal on ultrasound. If the rash develops in the mother during the five days before to two days after delivery, the neonate should be isolated and receive 125 units of VZIG, intramuscularly.14,19

Fifth Disease

BACKGROUND

Fifth disease (erythema infectiosum) is caused by human parvovirus B19, a single-stranded DNA virus that affects only humans.4 The disease is transmitted through respiratory secretions and hand-to-mouth transfer.

Children with fifth disease present with a widespread, lacy, erythematous rash with malar flushing (“slapped cheeks”). Adults with fifth disease are less likely to develop the facial rash and are more likely to have arthralgias, although 20 percent of adults are asymptomatic. Current guidelines do not recommend exclusion from the workplace where fifth disease is present because of the low risk to the fetus.20

FETAL AND NEONATAL INFECTION

Although human parvovirus B19 infections are not teratogenic, they can destroy erythroid precursors and cause fetal anemia, which may lead to subsequent heart failure, nonimmune hydrops and death.21 The rate of transplacental transmission is approximately 30 percent.22 When maternal infection occurs before 20 weeks of gestation, the rate of fetal loss is 9 percent. However, in one large series,23 the risk of fetal loss did not increase when maternal infection occurred after 20 weeks of gestation. Among infants who have survived infection with parvovirus, no abnormalities or late effects have been found after seven to 10 years of follow-up.23 After a household exposure to parvovirus, the risk of fetal death has been estimated as less than 2.5 percent; after a workplace exposure, the risk is less than 1.5 percent.2

POSTEXPOSURE MANAGEMENT

Pregnant women who have been exposed to parvovirus should undergo serologic testing. IgG antibodies are usually detectable by the seventh day of illness, persist indefinitely and, in the absence of IgM antibodies, indicate immunity. IgM antibodies appear three days after onset of the illness and may persist for 30 to 60 days. If susceptibility or recent infection is indicated by serology, weekly ultrasound examinations should be performed for four to eight weeks after exposure (or two to six weeks after infection) to detect hydrops. Fetal transfusion may be considered for hydropic fetuses, although spontaneous resolution has occurred.4

Cytomegalovirus

BACKGROUND

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is the most common congenital infection, occurring in 1 percent of all pregnancies. Infection does not confer lifelong immunity. Reactivation of latent CMV is more common during pregnancy, but fetal damage from reactivation is rare.7 Transmission occurs through contact with saliva or urine, or through sexual contact.

Because CMV infections are asymptomatic, most are not detected. Occasionally, infected patients will develop hepatitis, pneumonia, thrombocytopenia, a mononucleosis-like illness or Guillain-Barré syndrome.2 More typical presentations include patients with unexpected elevation of liver enzymes or pregnant nurses who discover that they have been caring for patients infected with CMV.

Women who develop a heterophile-negative mononucleosis syndrome should be tested for CMV infection and toxoplasmosis. Women who work in health care or day care settings should use universal precautions, wash their hands after handling diapers and avoid nuzzling infants.4 Prenatal serologic screening for CMV infection is not recommended, even in high-risk patients, because test interpretation is difficult and seroreactivity does not preclude perinatal transfer of infection.4

FETAL AND NEONATAL INFECTION

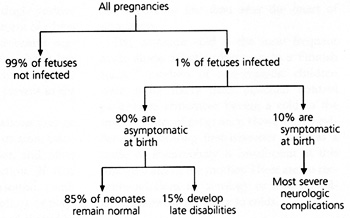

CMV can damage the fetus at any stage of pregnancy.7 About 1 percent of all newborns are infected with CMV in utero, but 90 percent of these newborns are asymptomatic and appear normal at birth (Figure 2).2 Among infected infants who are asymptomatic at birth, 10 to 20 percent develop late neurologic sequelae such as hearing loss, psychomotor retardation, expressive-language delays and learning disabilities.2

About 10 percent of infants who become infected with CMV in utero develop cytomegalic inclusion disease, which is characterized by hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, thrombocytopenia, chorioretinitis, optic atrophy, mental retardation, cerebral calcifications, deafness and microcephaly.2 Infants who are symptomatic at birth have a high rate of mortality and a high risk of developing neurologic manifestations.

POSTEXPOSURE MANAGEMENT

CMV infection in the mother can be diagnosed by a fourfold rise in IgG antibody titer over a 14- to 21-day period. A single positive test is not helpful because 50 percent of adults have the antibody. Primary infection is suggested by the presence of IgM antibodies, but seroconversion is a more accurate sign of infection because IgM may be present in the absence of acute infection.20

Periodic ultrasound examinations may be used to detect fetal growth restriction, calcifications in the brain and liver, and other manifestations of CMV infection. If fetal infection is suspected on ultrasound, amniotic fluid can be obtained for culture or polymerase chain reaction. Fetal blood should be tested for IgM antibodies, gamma-glutaryltransferase, hemoglobin and platelet count. Decisions about the termination of pregnancy are often complex and usually require consultation.

Influenza and the Common Cold

Influenza-specific antibody is transmitted to the fetus in utero and protects the newborn. However, susceptible newborns are at increased risk for influenza, with manifestations ranging from mild coryza to sepsis. Amantadine (Symmetrel) may be teratogenic and should be given only in unusual circumstances, such as severe influenza pneumonia. If influenza occurs in late pregnancy, delivery should be delayed until the mother has recovered, if possible, to allow the newborn to acquire transplacental antibodies. This usually occurs by five days after the onset of symptoms.

The common cold is the most frequent acute illness affecting humans. In a Finnish study,30 mothers of anencephalic children were more likely than matched control patients to remember having a cold in the first trimester of pregnancy. However, the evidence implicating first-trimester colds as a cause of anencephaly is insufficient at this time to concern the mother. There are no recommendations for serology or fetal surveillance following exposure to colds.

Rubella

Before the vaccine became available in 1969, congenital rubella was a major cause of malformations in neonates. Now, fewer than 20 cases are reported each year.2 While the vaccine has not caused malformations, it should be avoided during pregnancy and contraception should be used for three months after vaccination. The susceptible mother should be vaccinated in the immediate postpartum period, regardless of whether she plans to breast-feed.31

The risk to the fetus varies with gestational age (Table 1). Pregnant women who are exposed to rubella should have immediate serologic evaluation for IgG and IgM. If primary rubella is diagnosed in the first trimester of pregnancy, the patient should be counseled about the option to undergo termination of pregnancy.2 If IgG antibody is present at the time of exposure, the mother should be reassured that she is immune.31

Other Viruses

Isolated reports of fetal malformation are associated with other respiratory viruses. However, the lack of consistent patterns justifies reassurance for mothers who have been exposed to measles,2 mumps,2,4,7 adenoviruses, respiratory syncytial virus (bronchiolitis),19,32 Epstein-Barr virus (infectious mononucleosis)1,33 and human herpesvirus 6 (roseola).34 First-trimester infection with mumps or human herpesvirus 6 may increase the risk of spontaneous abortion,34,35 but an increase in the risk from measles, infectious mononucleosis or respiratory syncytial virus has not been documented.

Pregnancy Termination

We favor nondirective counseling of the patient about the termination of pregnancy. The mother is informed about the possibility of termination, but is also given maximum information about the risk of malformation. Patients may be told that the baseline risk of major malformations for all pregnancies is 2 to 3 percent. Chickenpox, for example, would add another 2 percent for a total risk of 4 to 5 percent. In such discussions, the severity of he malformation is often conveyed better than its likelihood. These issues are difficult to communicate clearly, and a thorough discussion will often involve consultation.