This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(4):631-639

Physicians who work in primary care settings and emergency departments frequently evaluate patients with neck and back pain. Spinal cord emergencies are uncommon, but injury must be recognized early so that the diagnosis can be quickly confirmed and treatment can be instituted to possibly prevent permanent loss of function. The differential diagnosis includes spinal cord compression secondary to vertebral fracture or space-occupying lesion, spinal infection or abscess, vascular or hematologic damage, severe disc herniation and spinal stenosis. The most important information in the assessment of a possible spinal cord emergency comes from the history and the clinical evaluation. Physicians must look for “red flags”—key historical and clinical clues that increase the likelihood of a serious underlying disorder. In considering diagnostic tests, physicians should apply the principles outlined in an algorithm for the evaluation of low back pain prepared by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (formerly the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research). Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can clearly define anatomy, but these studies are costly and have a high false-positive rate. Referral of high-risk patients to a neurologist or spine specialist may be indicated.

Spinal cord injuries are critical emergencies that must be recognized and treated early to increase the possibility of preventing permanent loss of function.1 The history and clinical presentation can provide the most important information in the assessment of a possible emergency.2–4 The physician must first look for “red flags”—historical and clinical clues that may indicate the presence of a serious underlying disorder (Table 1).5 In determining the appropriate laboratory and imaging studies, the physician should follow the approach to low back pain given in an algorithm (Figure 1) prepared by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (formerly the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research).3

Anatomy, Physiology and Pathology

The spine is divided into four sections: the cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacrococcygeal vertebrae.

The anterior column of the spine includes the anterior longitudinal ligament, anterior portion of the vertebral body and anterior portion of the intervertebral disc. The middle column is composed of the posterior longitudinal ligament, posterior body and posterior intervertebral disc. The posterior column includes the ligamentum flavum and the posterior elements (facet joints, pedicles, transverse processes, laminae and spinous processes). Surrounding these elements are multiple ligaments and muscles. The spinal cord and nerve roots are protected within these structures.6

The intervertebral disc is composed of the outer annulus fibrosus and the inner nucleus pulposus. The annulus fibrosus is made of lamelliform connective tissue bands. The nucleus pulposus is composed of mucinous, colloidal gel (proteoglycans and collagen, with a high water content [70 to 80 percent fluid]). The intervertebral disc absorbs shock, provides resistance to compression and allows flexibility of the vertebral column.7 A compromised (degenerated or anatomically abnormal) disc lends itself to abnormal motion and herniation of the nucleus pulposus, with potential radiculopathy and pain.

The spinal cord tapers caudally to become the conus medullaris. In the adult, the spinal cord terminates at the L1-L2 level. The nerve roots of the lumbosacral plexus make up the cauda equina.

The spinal cord is enveloped by three layers of meninges. The dura mater of the spinal cord is separated from the periosteum of the vertebrae by an epidural space. This space allows for processes such as bleeding, neoplasm and infection to reach an advanced stage before neurologic sequelae are noted.7

History

The history is key to the evaluation of spinal lesions. If pain is the presenting symptom, the physician must ask about the location, radiation and duration of the pain. The physician should also ask about the specific characteristics and severity of pain and whether the pain is present at night.6 It is also important to inquire about factors that exacerbate or relieve pain and other symptoms. Morning stiffness may be indicative of a rheumatologic arthropathy. Radicular pain may direct the evaluation to a specific nerve root level.

The patient should be asked about paresthesias, numbness or weakness. Muscle weakness, if progressive, must be evaluated urgently. Bowel and bladder symptoms with perianal numbness may be indicative of cauda equina syndrome, a true emergency that requires urgent decompression.

Several elements in the patient's medical history may be thought of as red flags (Table 1),5 although some conditions can make spinal pathology particularly difficult to evaluate (Table 2).1 In situations in which it may be extremely difficult to interpret nonclassic signs and symptoms, the physician's best judgment should be used to determine whether diagnostic testing or referral to a spine specialist is indicated.

Physical Examination

The physician should examine the entire spine for areas of redness, scars, blisters, lipomata, hairy patches, birthmarks and café-aulait spots. The spine should also be palpated for bony abnormalities, deviation from the midline and tenderness.

Range of motion, including flexion, extension, lateral rotation and lateral bending, should be assessed.7 In general, patients with disc disorders have pain with forward flexion, whereas patients with spinal stenosis have pain with extension of the lumbar spine.

Gait should also be assessed. The patient should be asked to toe walk and heel walk as part of the evaluation of motor strength.6

An important aspect of the physical examination is a rectal examination to assess sphincter tone, especially if the patient mentions bowel or bladder dysfunction.

The physician should perform a systematic, thorough motor and sensory examination of the patient's extremities (Tables 3 and 47). Chronic mild neurologic deficits involving a single nerve root may not necessarily be considered a red flag because these deficits are common in patients with degenerative pathologies such as disc herniation and lateral stenosis. However, a more aggressive approach is required when a patient has progressive neurologic deficits.2

| Mental illness, retardation or dementia |

| Severe, disabling pain |

| Moderate to severe polyneuropathy (e.g., in diabetes, alcoholism, etc.) that may mask or be confused with signs and symptoms of spinal cord pathology |

| Perceived drug-seeking behavior |

| Secondary-gain issues (e.g., legal actions, workers' compensation) |

Babinski's sign and hyperreflexia are widely understood to be cardinal signs of the upper motor neuron syndrome that typically occurs in spinal cord compression. The physician should be aware that, if present, a positive (abnormal) Babinski's sign is helpful, but a negative or absent sign does not exclude severe disease. One emergency department study found that nine patients who presented with severe myelopathy had a low incidence of extensor plantar responses and hyperreflexia.1

| Spinal nerve root level | Evaluation of motor function | |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical | ||

| C5 | Abduct arm | |

| C6, C7, C8 | Adduct arm | |

| C5, C6 | Flex elbow | |

| C7, C8 | Extend elbow | |

| C6 | Pronate and supinate forearm | |

| C6, C7 | Flex and extend wrist | |

| C7, C8 | Flex and extend fingers | |

| Thoracic | ||

| T1 | Abduct and adduct fingers | |

| Lumbar | ||

| L1, L2, L3 | Flex, adduct and medially rotate hip | |

| L3, L4 | Extend knee | |

| L4, L5 | Dorsiflex and invert ankle | |

| L5 | Extend toe (extensor hallucis longus) | |

| Sacral | ||

| S1 | Evert ankle | |

| S1, S2 | Flex plantar | |

Diagnostic Tests

LABORATORY TESTS

The laboratory evaluation may include a complete blood cell count with differential, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate and a urinalysis. The findings of the clinical evaluation may indicate the need for other specific tests, such as a serum calcium level, a uric acid level, electrophoresis of serum and urine for light chains, and a prostate-specific antigen level. Laboratory tests are particularly useful when infection or malignancy is considered to be a possible cause of the spinal pathology.

IMAGING STUDIES

Imaging studies are extremely important in the evaluation of spinal cord emergencies. Unless a red flag is noted on the clinical examination, plain-film radiographs are not recommended for the routine evaluation of patients with acute neck or low back pain within the first month of symptoms3 (Table 1).5

Computed tomographic (CT) scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), myelography and combined CT and myelography can clearly define anatomy. However, these studies are costly and have a high false-positive rate.8

Because MRI is noninvasive, does not involve radiation, covers a large area of the spine and can show changes within the disc and vertebral body, it has become the imaging modality of choice in the diagnosis of radiculopathy, spinal cord abscesses, spinal cord tumors, spinal stenosis and nontraumatic vascular lesions.8–12 Using the magnetic resonance images in the fast sequence results in a myelography-like appearance that allows rapid screening of the spinal canal with high sensitivity for epidural masses.9 Chelated gadolinium further enhances MRI studies.

Compared with MRI studies, CT scans provide better imaging of bony structures. Hence, CT scanning is considered the imaging modality of choice to evaluate patients for spinal trauma and vertebral fractures.8 CT scanning is less sensitive to patient movement than MRI, and it can be used in patients with pacemakers, ferromagnetic vascular clips and other implanted devices. CT scanning is less expensive than MRI.

Bone scanning can be useful when plainfilm radiographs of the spine are normal but the clinical findings are suspicious for osteomyelitis, bony neoplasm or occult fracture. Although bone scanning is a sensitive screening tool for bony tumors and infections, results are false-positive in one third of older patients, who are at highest risk for these conditions and have a high incidence of osteoarthritis.8

Differential Diagnosis and Treatment

NEOPLASTIC DISEASES

Metastatic spinal disease is 25 times more common than primary tumors of the spine. The most prevalent metastatic neoplasms are breast, lung, prostate and kidney tumors, and lymphoma.7

Plain-film radiographs may not visualize early spinal metastasis, but bone scans are positive in 85 percent of patients with metastatic spinal disease. MRI studies may identify spinal metastasis in patients with normal radiographs and bone scans (Figure 2).

Primary spinal neoplasms are encountered far less frequently in adults than in children. Multiple myeloma is the most common of these tumors in adults.4

Epidural spinal cord compression from metastatic cancer is common and serious but potentially treatable. This complication affects the thoracic spine in approximately two thirds of patients, the lumbosacral spine in about one fifth of patients and the cervical spine in the remainder of patients.13

Acute myelopathy in patients with cancer may also be caused by irradiation, paraneoplastic necrotizing myelitis, ruptured intervertebral disc and meningeal carcinomatosis with spinal cord involvement.

The pain produced by spinal neoplasm is often worse when the patient is at rest and may even awaken the patient from a sound sleep. Other symptoms include weakness (75 percent of patients) and autonomic or sensory symptoms (50 percent of patients). The neurologic examination usually reveals symmetric weakness with either flaccidity and hyporeflexia (if the diagnosis is made early) or spasticity and hyperreflexia (if the diagnosis is made later).13

The sudden onset of myelopathy secondary to spinal metastasis is a true neurologic emergency. Pretreatment, high-dose corticosteroid therapy may be initiated to reduce cord edema and alleviate pain, and immediate consultation with a neurosurgeon and radiation oncologist is indicated. Radiation therapy is the standard approach. Surgery is indicated if the diagnosis is in doubt, a tissue diagnosis is required, the spine is unstable or neurologic deterioration is severe, rapid and progressive. Surgery is also indicated if decompression by radiation therapy is not expected to become effective in time to save a patient from severely disabling neurologic deficits.7

INFECTIONS

Spinal infections may be acute (bacterial infections) or chronic (e.g., fungal or tuberculous infections).

Spinal osteomyelitis should be suspected in a patient who has recently undergone a spinal procedure and has focal severe pain that is not relieved by rest. An epidural abscess may develop as a result of adjacent vertebral osteomyelitis or discitis, as well as hematogenous spread from a remote infection. New acute onset of neck or back pain in a patient with a history of recent infection or current fever and elevations of the white blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate should raise suspicion of spondylodiscitis.

Tuberculosis has a predilection for the spine where it can affect adjacent vertebral bodies. Tuberculous infection may result in vertebral collapse and a sharply angulated deformity (Pott's disease).2

VASCULAR OR HEMATOLOGIC DAMAGE

Rarely, back pain is caused by an epidural hematoma, resulting in a presentation similar to that of acute lumbar disc herniation.15 Patients with epidural hematoma usually have a history of recent spinal procedure or trauma. An epidural hematoma can also develop in a patient who is prone to bleeding because of, for example, anticoagulant therapy.

TRAUMA

According to the National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center, data from state trauma registries suggest that approximately 10,000 spinal cord injuries occur in the United States each year.5 Motor vehicle crashes account for 37 percent of these injuries, crimes of violence for 26 percent, falls for 24 percent and sports injuries for 7 percent (most commonly incurred in football and ice hockey).5,16

The mechanism of most spinal cord injuries is spinal fracture or dislocation. One half of spinal fractures occur in the cervical vertebrae, one sixth in the thoracic vertebrae and one third in the lumbosacral vertebrae.5

Trauma is the most common cause of complete transection of the spinal cord. Below the level of the lesion, motor, sensory, reflex and autonomic (including sphincter) function is lost. True hemisection of the spinal cord (Brown-Séquard syndrome) is rare and usually associated with penetrating trauma. This injury is characterized by ipsilateral loss of motor function and proprioception, with contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation.7

The criteria for ordering plain-film radiographs of the cervical spine are summarized in Table 5,5 and the recommended indications for CT scanning are summarized in Table 65 The initial evaluation of suspected injury to the cervical spine includes a cross-table lateral plain-film radiograph with the patient supine. If the lateral projection is inadequate, a swimmer's projection, oblique projections or a CT scan is indicated.

Lateral radiographs of the cervical spine must always be followed by anteroposterior and open-mouth projections. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the thoracic or lumbar regions are indicated in patients with localized tenderness or a suspicious mechanism of injury. Because there is a 10 to 15 percent incidence of spinal fractures at more than one site, consideration must always be given to radiographic examination of the entire spine when one fracture is identified.7

DISC HERNIATION

Patients with disc herniation usually present with the acute onset of low back pain that radiates into the buttocks and thighs and down one leg. The most common levels of involvement are L4-L5 and L5-S1. The straight-leg-raise test is sensitive but nonspecific for the identification of herniated discs.6

As a disc herniation becomes more central, more than one nerve root can be involved. With large herniations, the cauda equina also becomes involved. In this situation, motor weakness is present in both lower extremities, and the bladder and bowel can be paralyzed. Emergency MRI is indicated. If a patient presents with cauda equina syndrome, early decompression should be performed. Waiting longer than 72 hours increases the risk of permanent neurologic deficits.

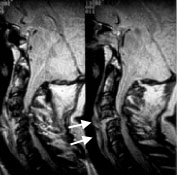

Herniation of a cervical disc is not uncommon. The presentation is similar to that for lumbar disc herniation (i.e., pain, tingling and weakness in the distribution of one nerve root to the upper extremity). MRI is the modality of choice for identifying cervical disc herniation (Figure 5).

SPINAL STENOSIS

Spinal stenosis is usually a degenerative condition resulting from hypertrophy of the facet joints (osteoarthritis), hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum and vertebral degeneration with bulging of the intervertebral disc. These degenerative changes can be superimposed on a congenitally narrow canal.18

[ corrected] Lumbar spinal stenosis may result in neurogenic claudication. In this condition, leg pain is brought on by walking and is relieved by sitting. Spinal stenosis may also be associated with cauda equina syndrome. An MRI study that reveals a narrow spinal canal can confirm the diagnosis of spinal stenosis.