A more recent article on pleural effusion is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(7):1211-1220

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

The first step in the evaluation of patients with pleural effusion is to determine whether the effusion is a transudate or an exudate. An exudative effusion is diagnosed if the patient meets Light’s criteria. The serum to pleural fluid protein or albumin gradients may help better categorize the occasional transudate misidentified as an exudate by these criteria. If the patient has a transudative effusion, therapy should be directed toward the underlying heart failure or cirrhosis. If the patient has an exudative effusion, attempts should be made to define the etiology. Pneumonia, cancer, tuberculosis, and pulmonary embolism account for most exudative effusions. Many pleural fluid tests are useful in the differential diagnosis of exudative effusions. Other tests helpful for diagnosis include helical computed tomography and thoracoscopy.

Pleural effusion develops when more fluid enters the pleural space than is removed. Potential mechanisms of fluid increased interstitial fluid in the lungs secondary to increased pulmonary capillary pressure (i.e., heart failure) or permeability (i.e., pneumonia); decreased intrapleural pressure (i.e., atelectasis); decreased plasma oncotic pressure (i.e., hypoalbuminemia); increased pleural membrane permeability and obstructed lymphatic flow (e.g., pleural malignancy or infection); diaphragmatic defects (i.e., hepatic hydrothorax); and thoracic duct rupture (i.e., chylothorax). Although many different diseases may cause pleural effusion, the most common causes in adults are heart failure, malignancy, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and pulmonary embolism, whereas pneumonia is the leading etiology in children.1,2

| Clinical recommendations | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Thoracentesis should be performed in all patients with more than a minimal pleural effusion unless clinically evident heart failure is present. | C | 5,33 |

| An effusion is exudative if it meets any of the following three criteria: (1) the ratio of pleural fluid protein to serum protein is greater than 0.5, (2) the pleural fluid lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to serum LDH ratio is greater than 0.6, (3) pleural fluid LDH is greater than two thirds of the upper limit of normal for serum LDH. | C | 1,5,8 |

| The serum-effusion protein or albumin gradients can be used to diagnose the presence of a transudate after diuresis. | C | 1,9,10 |

| In a lymphocyte-predominant exudate, a pleural fluid adenosine deaminase greater than 40 U per L (667 nkat per L) indicates that the most likely diagnosis is tuberculosis. | C | 26–28 |

| If malignancy is a concern and cytologic examination is nondiagnostic, thoracoscopy should be considered. | C | 5,39,40 |

Initial Evaluation of Pleural Effusion

The history and physical examination are critical in guiding the evaluation of pleural effusion (Table 1). Signs and symptoms of an effusion vary depending on the underlying disease, but dyspnea, cough, and pleuritic chest pain are common. Chest examination of a patient with pleural effusion is notable for dullness to percussion, decreased or absent tactile fremitus, decreased breath sounds, and no voice transmission.

| Condition | Potential causes of the pleural effusion |

|---|---|

| History | |

| Abdominal surgical procedures | Postoperative pleural effusion, subphrenic abscess, pulmonary embolism |

| Alcohol abuse or pancreatic disease | Pancreatic effusion |

| Artificial pneumothorax therapy | Tuberculous empyema, pyothorax-associated lymphoma, trapped lung |

| Asbestos exposure | Mesothelioma, benign asbestos pleural effusion |

| Cancer | Malignancy |

| Cardiac surgery or myocardial injury | Pleural effusion secondary to coronary artery bypass graft surgery or Dressler’s syndrome |

| Chronic hemodialysis | Heart failure, uremic pleuritis |

| Cirrhosis | Hepatic hydrothorax, spontaneous bacterial empyema |

| Childbirth | Postpartum pleural effusion |

| Esophageal dilatation or endoscopy | Pleural effusion secondary to esophageal perforation |

| Human immunodeficiency virus infection | Pneumonia, tuberculosis, primary effusion lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma |

| Medication use | Medication-induced pleural disease |

| Remote inflammatory pleural process | Trapped lung |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Rheumatoid pleuritis, pseudochylothorax |

| Superovulation with gonadotrophins | Pleural effusion secondary to ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Lupus pleuritis, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism |

| Trauma | Hemothorax, chylothorax, duropleural fistula |

| Signs | |

| Ascites | Hepatic hydrothorax, ovarian cancer, Meigs’ syndrome |

| Dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, peripheral edema, elevated jugular venous pressure | Heart failure, constrictive pericarditis |

| Pericardial friction rub | Pericarditis |

| Unilateral lower extremity swelling | Pulmonary embolism |

| Yellowish nails, lymphedema | Pleural effusion secondary to yellow nail syndrome* |

| Symptoms | |

| Fever | Pneumonia, empyema, tuberculosis |

| Hemoptysis | Lung cancer, pulmonary embolism, tuberculosis |

| Weight loss | Malignancy, tuberculosis, anaerobic bacterial pneumonia |

Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs usually confirm the presence of a pleural effusion, but if doubt exists, ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scans are definitive for detecting small effusions and for differentiating pleural fluid from pleural thickening.3 Small amounts of pleural fluid not readily seen on the standard frontal view may be recognized in a lateral decubitus view (Figures 1a and 1b). On a posteroanterior radiograph, free pleural fluid may blunt the costophrenic angle; form a meniscus laterally; or hide in a subpulmonic location, simulating an elevated hemidiaphragm.

Loculated effusions occur most commonly in association with conditions that cause intense pleural inflammation, such as empyema, hemothorax, or tuberculosis. Occasionally, a focal intrafissural fluid collection may look like a lung mass. This situation most commonly is seen in patients with heart failure. The disappearance of the apparent mass when the heart failure is treated definitively establishes the diagnosis of pseudotumor (i.e., vanishing tumor). Heart failure is by far the most common cause of bilateral pleural effusion, but if cardiomegaly is not present, other causes such as malignancy should be investigated.

Large effusions may opacify the entire hemithorax and displace mediastinal structures toward the opposite side. More than one half of these massive pleural effusions are caused by malignancy; other causes are complicated parapneumonic effusion, empyema, and tuberculosis.4 If the mediastinum is shifted toward the side of the effusion or is midline in a patient with a massive pleural effusion, either an endobronchial obstruction (e.g., lung cancer) or a mediastinum encasement by tumor (e.g., mesothelioma) should be considered.

Thoracentesis

Except for patients with obvious heart failure, thoracentesis should be performed in all patients with more than a minimal pleural effusion (i.e., larger than 1 cm height on lateral decubitus radiograph, ultrasound, or CT) of unknown origin.5 In the context of heart failure, diagnostic thoracentesis is only indicated if any of the following atypical circumstances is present:1,5 (1) the patient is febrile or has pleuritic chest pain; (2) the patient has a unilateral effusion or effusions of markedly disparate size; (3) the effusion is not associated with cardiomegaly, or (4) the effusion fails to respond to management of the heart failure.

Thoracentesis is urgent when it is suspected that blood (i.e., hemothorax) or pus (i.e., empyema) is in the pleural space, because immediate tube thoracostomy is indicated in these situations. If difficulty in obtaining pleural fluid is encountered because the effusion is small or loculated, ultrasound-guided thoracentesis minimizes the risk for iatrogenic pneumothorax.6 In most instances, analysis of the pleural fluid yields valuable diagnostic information or definitively establishes the cause of the pleural effusion. This is the case when malignant cells, microorganisms, or chyle are found, or when a transudative effusion is found in the setting of heart failure or cirrhosis.

Observing the gross appearance of the pleural fluid may suggest a particular cause. For example, turbidity of the pleural fluid can be caused either by cells and debris (i.e., empyema) or by a high lipid level (i.e., chylothorax). A uniformly blood-stained fluid (i.e., hematocrit greater than 1 percent) narrows the differential diagnosis of the pleural effusion to malignancy, trauma (including recent cardiac surgery), pulmonary embolism, and pneumonia.3,7 If the hematocrit of the pleural fluid exceeds half the simultaneous peripheral blood hematocrit, the patient has hemothorax.

Although common, chest radiography is not necessary after thoracentesis unless air is obtained during the procedure; the patient develops symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, or chest pain; or tactile fremitus is lost over the upper part of the aspirated hemithorax.5

Analysis of Pleural Fluid

Pleural effusions are either transudates or exudates based on the biochemical characteristics of the fluid, which usually reflect the physiologic mechanism of its formation.

TRANSUDATIVE EFFUSIONS

Transudates result from imbalances in hydrostatic and oncotic forces and are caused by a limited number of recognized clinical conditions such as heart failure and cirrhosis. Less common causes include nephrotic syndrome, atelectasis, peritoneal dialysis, constrictive pericarditis, superior vena caval obstruction, and urinothorax. Transudative effusions usually respond to treatment of the underlying condition (e.g., diuretic therapy).

EXUDATIVE EFFUSIONS

| Cause | Annual incidence | Transudate | Exudate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Congestive heart failure | 500,000 | Yes | No |

| Pneumonia | 300,000 | No | Yes |

| Cancer | 200,000 | No | Yes |

| Pulmonary embolism | 150,000 | Sometimes | Sometimes |

| Viral disease | 100,000 | No | Yes |

| Coronary-artery bypass surgery | 60,000 | No | Yes |

| Cirrhosis | 50,000 | Yes | No |

In clinical practice, exudative effusions can be separated effectively from transudative effusions using Light’s criteria. These criteria classify an effusion as exudate if one or more of the following are present: (1) the ratio of pleural fluid protein to serum protein is greater than 0.5, (2) the ratio of pleural fluid lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to serum LDH is greater than 0.6, or (3) the pleural fluid LDH level is greater than two thirds of the upper limit of normal for serum LDH.

Light’s criteria are nearly 100 percent sensitive at identifying exudates, but approximately 20 percent of patients with pleural effusion caused by heart failure may fulfill the criteria for an exudative effusion after receiving diuretics.8 In these circumstances, if the difference between protein levels in the serum and the pleural fluid is greater than 3.1 g per dL, the patient should be classified as having a transudative effusion.9 A serum-effusion albumin gradient greater than 1.2 g per dL also can indicate that the pleural effusion is most likely a true transudative effusion.10 However, neither protein nor albumin gradients alone should be the primary test used to distinguish transudative effusions from exudative effusions because they result in the incorrect classification of a significant number of exudates. This lower sensitivity may be caused by the fact that a single test is employed as opposed to the three-test combination of the standard criteria described above. Another approach to the classification of pleural effusions is to apply continuous or multilevel likelihood ratios (Table 311).

| Pleural fluid to serum protein ratio | Likelihoodratio* | Probability of exudate with overall risk of 10% (%) | Probability ofexudate with overall risk of 30% (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥0.71 | 93.03 | 91.0 | 98.0 |

| 0.66 to 0.70 | 31.81 | 78.0 | 93.0 |

| 0.61 to 0.65 | 4.24 | 32.0 | 64.0 |

| 0.56 to 0.60 | 3.58 | 29.0 | 61.0 |

| 0.51 to 0.55 | 1.50 | 14.0 | 39.0 |

| 0.46 to 0.50 | 0.48 | 5.3 | 18.0 |

| 0.41 to 0.45 | 0.27 | 3.2 | 11.0 |

| 0.36 to 0.40 | 0.15 | 2.2 | 7.9 |

| 0.31 to 0.35 | 0.07 | 1.1 | 4.1 |

| ≤0.30 | 0.04 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

FURTHER TESTING FOR EXUDATES

In patients with exudative effusion, the following pleural fluid tests should be performed on fluid obtained during the initial thoracentesis: cell counts and differential, glucose, adenosine deaminase (ADA), and cytologic analysis. Bacterial cultures and pH should be tested if infection is a concern12 (Tables 43,5,13 and55,13–24).

Pleural fluid for total white blood cell (WBC) count and differential cell count should be sent in an anticoagulated tube. If the fluid is sent in a plastic or glass tube without anticoagulation, the fluid may clot, resulting in an inaccurate count.25 The predominant WBC population is determined by the mechanism of pleural injury and the timing of the thoracentesis in relation to the onset of the injury. Thus, the finding of neutrophilrich fluid heightens suspicion for parapneumonic pleural effusion (an acute process), whereas a lymphocyte-predominant fluid profile suggests cancer or tuberculosis (a chronic process).

| Test | Test value | Suggested diagnosis | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenosine deaminase (ADA) | > 40 U per L (667 nkat per L) | Tuberculosis (> 90 percent), empyema (60 percent), complicated parapneumonic effusion (30 percent), malignancy (5 percent), rheumatoid arthritis5 | In the United States, ADA is not routinely requested because of the low prevalence of tuberculous pleurisy. |

| Cytology | Present | Malignancy | Actively dividing mesothelial cells can mimic an adenocarcinoma. |

| Glucose | < 60 mg per dL (3.3 mmol per L) | Complicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema, tuberculosis (20 percent), malignancy (< 10 percent), rheumatoid arthritis5 | In general, pleural fluids with a low glucose level also have low pH and high LDH levels. |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | > Two thirds of upper limits of normal for serum LDH | Any condition causing an exudate | Very high levels of pleural fluid LDH (> 1,000 U per L) typically are found in patients with complicated parapneumonic pleural effusion and in about 40 percent of those with tuberculous pleurisy.5 |

| LDH fluid toserum ratio | > 0.6 | Any condition causing an exudate | Most patients who meet the criteria for an exudative effusion with LDH but not with protein levels have either parapneumonic effusions or malignancy.3 |

| Protein fluid to serum ratio | > 0.5 | Any condition causing an exudate | A pleural fluid protein level > 3 mg per dL suggests an exudate, but when taken alone this parameter misclassifies more than 10 percent of exudates and 15 percent of transudates.13 |

| Red blood cell count | > 100,000 per mm3 (100 × 106 per L) | Malignancy, trauma, parapneumonic effusion, pulmonary embolism | A fluid hematocrit < 1 percent is nonsignificant.13 |

| White blood cell count and differential | > 10,000 per mm3 (10 ×3 109 per L) | Empyema, other exudates (uncommon) | In purulent fluids, leukocyte count is commonly much lower than expected because dead cells or other debris account for much of the turbidity. |

| Eosinophils | > 10 percent | Not diagnostic | The presence of air or blood in the pleural space is a common cause. No diagnosis is ever obtained in as many as one third of patients with eosinophilic pleural effusion.3 |

| Lymphocytes | > 50 percent | Malignancy, tuberculosis, pulmonary embolism, coronary artery bypass surgery | Pleural fluid lymphocytosis > 90 percent suggests tuberculosis or lymphoma. |

| Neutrophils | > 50 percent | Parapneumonic effusion, pulmonary embolism, abdominal diseases | In about 7 percent of acute tuberculous pleurisy and 20 percent of malignant pleural effusions, a neutrophilic fluid predominance can be seen.5 |

Pleural fluid for pH testing should be collected anaerobically in a heparinized syringe and measured in a blood-gas machine.3 Frank pus should not be sent for pH determination because thick, purulent fluid may clog the blood-gas machine. A low pleural fluid pH value has prognostic and therapeutic implications for patients with parapneumonic and malignant pleural effusions. A pH value less than 7.20 in a patient with a parapneumonic effusion indicates the need to drain the fluid.14,15 In a patient with malignant pleural effusion, a pleural fluid pH value less than 7.30 is associated with a shorter survival and poorer response to chemical pleurodesis.1 When a pleural fluid pH value is not available, a pleural fluid glucose concentration less than 60 mg per dL can be used to identify complicated parapneumonic effusions.14

| Test | Test value | Suggested diagnosis | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amylase | > Upper limit of normal | Malignancy (<20 percent), pancreatic disease, esophageal rupture5,16 | Obtain when esophageal rupture or pancreatic disease is suspected. The amylase in malignancy and esophageal rupture is of the salivary type. |

| Cholesterol | > 45 to 60 mg per dL (1.16 to 1.55 mmol per L) | Any condition causing an exudate | Measure if chylothorax or pseudochylothorax is suspected. This parameter taken alone misclassifies 10 percent of exudates and 20 percent of transudates.13 |

| Culture | Positive | Infection | Obtain in all parapneumonic pleural effusions because a positive Gram stain or culture should lead to prompt chest tube drainage.14,15 |

| Hematocrit fluid to blood ratio | ≥0.5 | Hemothorax | Obtain when pleural fluid is bloody. Hemothorax most often originates from blunt or penetrating chest trauma. |

| Interferon* | Different cutoff points | Tuberculosis17 | Consider when ADA is unavailable or nondiagnostic and tuberculosis is suspected. |

| NT-proBNP | > 1,500 pg per mL | Heart failure18 | If available, consider testing when heart failure is suspected and exudate criteria are met.19 |

| pH | < 7.20 | Complicated parapneumonic effusion or empyema, malignancy (< 10 percent), tuberculosis (< 10 percent), esophageal rupture5 | Obtain in all nonpurulent effusions if infection is suspected. A low pleural fluid pH indicates the need for tube drainage only for parapneumonic pleural effusions. |

| Polymerase chain reaction † | Positive | Infection20,21 | Consider when infection is suspected. Sensitivity of polymerase chain reaction to detectMycobacterium tuberculosis in pleural fluid varies from 40 to 80 percent and is lower in patients with negative mycobacterial cultures. |

| Triglycerides | > 110 mg per dL (1.24 mmol per L) | Chylothorax | Obtain when pleural fluid is cloudy or milky. Chylothorax is caused by lymphoma or trauma. Not all chylous pleural effusions appear milky white or whitish. |

| Tumor markers‡ | Different cutoff points | Malignancy | Consider when malignancy is suspected and thoracoscopy is being considered. Except for telomerase activity,22 individual tests tend to have low sensitivity (< 30 percent) when looking for the utmost specificity.23,24 |

ADA is an enzyme that plays an important role in lymphoid cell differentiation. A pleural fluid ADA level greater than 40 U per L (667 nkat per L) has a sensitivity of 90 to 100 percent and a specificity of 85 to 95 percent for the diagnosis of tuberculous pleurisy.3,5,26–28 The specificity rises above 95 percent if only lymphocytic exudates are considered.29,30 In areas where the prevalence of tuberculosis is low, the positive predictive value of pleural ADA declines but the negative predictive value remains high.

Cultures for both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria will identify the responsible microorganism in about 40 percent of parapneumonic effusions (70 percent if fluid is grossly purulent).5 The yield with culture is increased if blood-culture bottles are inoculated at the bedside with the pleural fluid. In addition, both pleural fluid and sputum should be cultured for mycobacteria when tuberculous pleuritis is suspected. The yield of sputum cultures in tuberculous pleural effusion varies from 10 to 60 percent, largely dependent on the extent of associated pulmonary involvement.31 Because delayed hypersensitivity plays a major role in the pathogenesis of tuberculous pleuritis, it is not possible to isolateMycobacterium tuberculosis from pleural fluid samples in more than 60 to 70 percent of patients.5,26 The use of broth medium (e.g., BACTEC radiometric system) with bedside inoculation provides higher yields and faster results (one to two weeks) than conventional methods.32 Smears of the pleural fluid for mycobacteria are rarely positive (5 percent)5 unless the patient has a tuberculous empyema. About one third of patients with tuberculous pleuritis have a negative tuberculin skin test.26

Cytology is positive in approximately 60 percent of malignant pleural effusions.33 Negative test results are related to factors such as the type of tumor (e.g., commonly negative with mesothelioma, sarcoma, and lymphoma); the tumor burden in the pleural space; and the expertise of the cytologist. The diagnostic yield may be somewhat improved by additional pleural taps. Submission of 10 mL of pleural fluid appears adequate for cytologic processing.34

A second thoracentesis should be considered in the following situations: (1) suspected malignant effusion and the initial pleural fluid cytologic examination is negative; (2) a parapneumonic effusion with borderline biochemical characteristics of the pleural fluid for indicating chest tube drainage; and (3) suspected acute tuberculous pleurisy with initial nondiagnostic pleural ADA levels.

Other diagnostic procedures

IMAGING TECHNIQUES

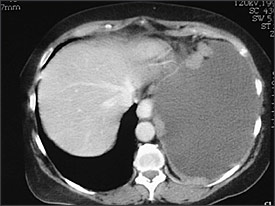

Helical CT has become the first-line modality for imaging of pulmonary circulation in a patient suspected of having pulmonary embolism, supplanting ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy. Helical CT also can identify alternative explanations for the pleural effusion, can diagnose deep venous thrombosis when combined with CT venography of the pelvis and lower extremities, and can distinguish malignant from benign pleural disease. CT findings suggestive of malignant disease are the presence of pleural nodules or nodular pleural thickening (Figure 2), circumferential or mediastinal pleural thickening, or infiltration of the chest wall or diaphragm. However, a recent study35 found that this was true in less than 20 percent of patients with malignant pleural effusion. Positron emission tomography seems promising for differentiating between benign and malignant pleural diseases (sensitivity 97 percent and specificity 88.5 percent in one study).36

BRONCHOSCOPY

Bronchoscopy is useful whenever an endobronchial malignancy is likely, as suggested by one or more of the following characteristics: a pulmonary infiltrate or a mass on the chest radiograph or CT scan, hemoptysis, a massive pleural effusion, or shift of the mediastinum toward the side of the effusion.

PERCUTANEOUS PLEURAL BIOPSY

Closed-needle biopsy of the pleura for histologic examination classically has been recommended for undiagnosed exudative effusions when tuberculosis or malignancy is suspected. The combination of histology (80 percent sensitivity) and culture (56 percent sensitivity) of pleural biopsy tissue establishes the diagnosis of tuberculosis in up to 90 percent of patients.3,5 However, this diagnosis is strongly suggested by a high ADA level in the pleural fluid, as detailed above, thus avoiding the need for a confirmatory biopsy in most patients.

Cytology is superior to blind pleural biopsy for the diagnosis of pleural malignancy. In one case series,37 needle biopsy of the pleura was positive in only 17 percent (20 of 119) of patients with malignancy involving the pleura but a negative pleural fluid cytology. The diagnostic yield from pleural biopsy is higher when it is used with some form of image guidance to identify areas of particular thickening or nodularity.38

THORACOSCOPY

Because thoracoscopy is diagnostic in more than 90 percent of patients with pleural malignancy and negative cytology, it is the preferred diagnostic procedure in patients with cytology-negative pleural effusion who are suspected of having pleural malignancy.39 Moreover, thoracoscopy offers the possibility of effective pleurodesis during the procedure.

Criteria for Referral

No diagnosis is ever established for approximately 15 percent of patients.1 Observation is probably the best option if the patient is improving and there are no parenchymal infiltrates or pleural nodules, because most pleural effusions that are undiagnosed after a thorough initial evaluation are benign.40,41 Figure 3 is a suggested algorithm for the investigation of pleural effusions.

Pulmonary consultation should be obtained when thoracentesis is technically difficult; the etiology is uncertain after initial thoracentesis; or drainage of the pleural space is advised (e.g., symptomatic large or massive pleural effusion, hemothorax, empyema, or complicated parapneumonic effusion).