Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(5):464-475

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

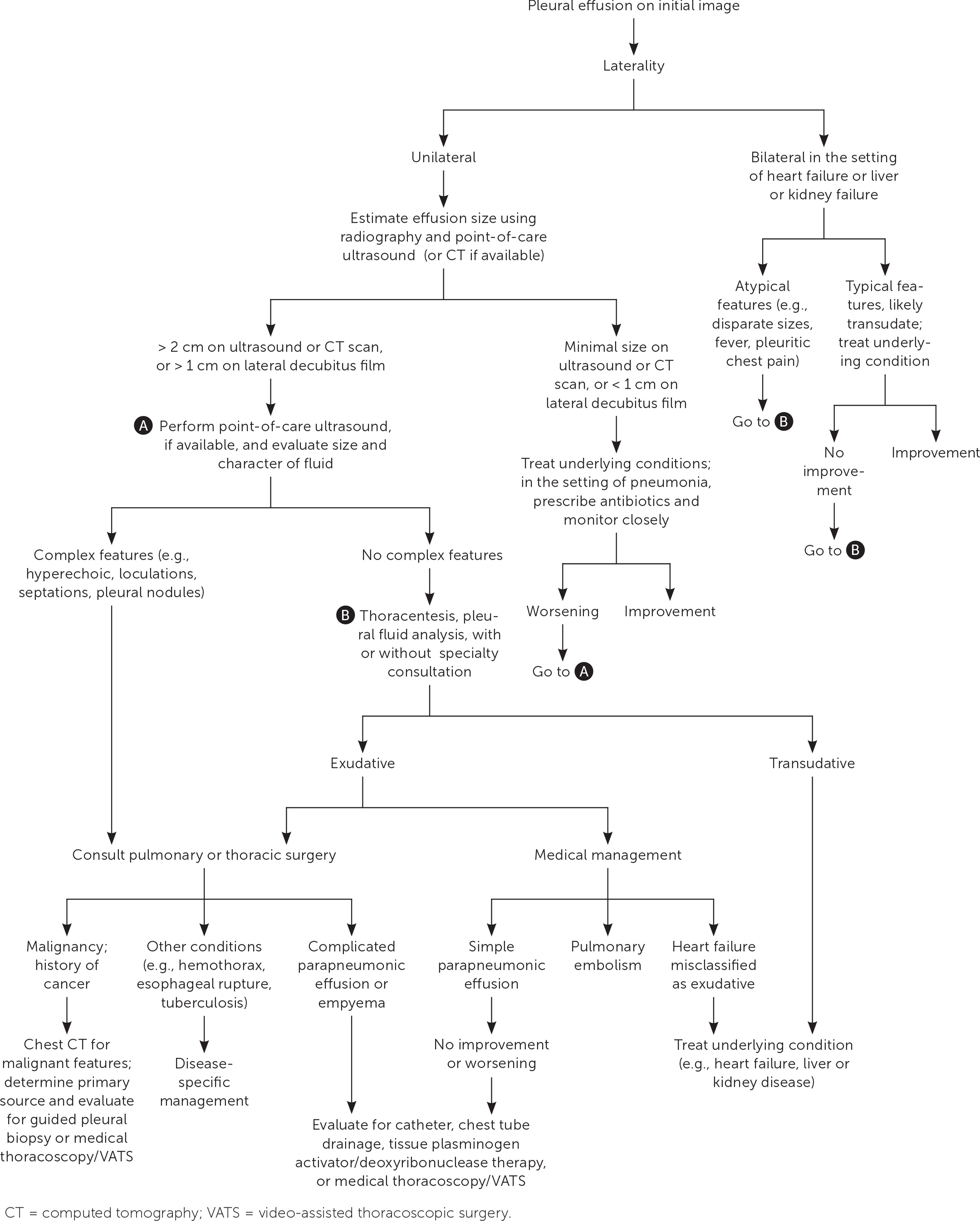

Pleural effusion affects 1.5 million patients in the United States each year. New effusions require expedited investigation because treatments range from common medical therapies to invasive surgical procedures. The leading causes of pleural effusion in adults are heart failure, infection, malignancy, and pulmonary embolism. The patient's history and physical examination should guide evaluation. Small bilateral effusions in patients with decompensated heart failure, cirrhosis, or kidney failure are likely transudative and do not require diagnostic thoracentesis. In contrast, pleural effusion in the setting of pneumonia (parapneumonic effusion) may require additional testing. Multiple guidelines recommend early use of point-of-care ultrasound in addition to chest radiography to evaluate the pleural space. Chest radiography is helpful in determining laterality and detecting moderate to large pleural effusions, whereas ultrasonography can detect small effusions and features that could indicate complicated effusion (i.e., infection of the pleural space) and malignancy. Point-of-care ultrasound should also guide thoracentesis because it reduces complications. Computed tomography of the chest can exclude other causes of dyspnea and suggest complicated parapneumonic or malignant effusion. When diagnostic thoracentesis is indicated, Light's criteria can help differentiate exudates from transudates. Pleural aspirate should routinely be evaluated using Gram stain, cell count with differential, culture, cytology, protein, l-lactate dehydrogenase, and pH levels. Additional assessments should be individualized, such as tuberculosis testing in high-prevalence regions. Parapneumonic effusions are the most common cause of exudates. A pH level less than 7.2 is indicative of complicated parapneumonic effusion and warrants prompt consultation for catheter or chest tube drainage, possible tissue plasminogen activator/deoxyribonuclease therapy, or thoracoscopy. Malignant effusions are another common cause of exudative effusions, with recurrent effusions having a poor prognosis.

Pleural effusion is excess fluid accumulation in the pleural space caused by disease or physiologic dysregulation and requires careful investigation to identify the underlying cause. A normal amount of pleural fluid (5 to 10 mL) is physiologic and allows for apposition and sliding of the visceral and parietal pleura and normal lung expansion. Pleural effusion results when fluid production exceeds absorption. Leading causes of pleural effusion in adults are heart failure, infection, malignancy, and pulmonary embolism.1,2 Transudative effusions are caused by disruptions in hydrostatic or oncotic pressures in heart failure, cirrhosis, or advanced kidney disease. Cirrhosis and portal hypertension may also cause ascitic fluid translocation across the diaphragm into the right hemithorax (hepatic hydrothorax). Inflammation of the pleural surface from pneumonia (parapneumonic effusion), malignancy, pulmonary embolism, medications,3 or autoimmune disease results in exudative fluid accumulation (Table 13–7).

| Causes | Transudative | Exudative | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common5 | Cirrhosis Heart failure Hepatic hydrothorax | Bacterial pneumonia Idiopathic Malignancy Lung cancer Lymphoma Metastasis (e.g., breast, colon) | Postcardiac bypass surgery Pulmonary embolism Trauma Tuberculosis Viral disease |

| Less common4 | Cardiovascular Superior vena cava obstruction Genitourinary Nephrotic syndrome (high risk for pulmonary embolism) Peritoneal dialysis Urinothorax Other Cerebrospinal fluid leak to pleura Myxedema | Cardiovascular Pericardial disease Post myocardial infarction Gastrointestinal Abdominal surgery Esophageal rupture Intra-abdominal infection Pancreatic disease Genitourinary Catamenial hemothorax (thoracic endometriosis) Meigs syndrome (benign ovarian tumor with ascites and pleural effusion) Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome Postpartum effusion Infectious Fungal infection Parasitic infection (lung fluke, amoebiasis, and echinococcus/ruptured hydatid cyst)6 | Pulmonary Benign asbestos effusion Mesothelioma Other Chylothorax (e.g., idiopathic, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, neoplasm, trauma, tuberculosis) Medication induced*3 Amiodarone Clozapine (Clozaril) Dantrolene (Dantrium) Ergot alkaloids Methotrexate Nitrofurantoin Phenytoin Tyrosine kinase inhibitors Pseudochylothorax (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis) Rheumatologic disorders Lupus Rheumatoid arthritis Yellow nail syndrome |

Diagnostic evaluation focuses on differentiating exudates from transudates, ordering appropriate fluid analysis, and determining the need for thoracentesis or specialist consultation. Accurate and early diagnosis is critical because treatments range from medical management to invasive surgery, with delays potentially causing complications and increased mortality.8

Epidemiology

Pleural effusion is common, especially in hospitalized adults. Effusions are associated with higher costs, morbidity, and mortality.9,10 Annually, 1.5 million patients in the United States have pleural effusions7; up to 1.3 million of these cases have nonmalignant causes.2 Annually, approximately 173,000 patients (12%) undergo thoracentesis.11 A prospective study in the United Kingdom found high one-year mortality rates for those with pleural effusions caused by heart failure (50%), malignancy (70%), and pneumonia (19%).12 A large study in China of patients with COVID-19 found low rates of pleural effusion (7% to 10%); however, effusion was associated with prolonged hospitalization and a sixfold increase in mortality.13

Clinical Features

The clinical features of pleural effusion can be insidious and challenging to recognize. The condition is typically diagnosed when imaging is ordered for a different reason. Symptoms include chronic dyspnea, cough, and pleuritic chest pain.4,8 Patients may be asymptomatic or progressively symptomatic based on the rate of fluid accumulation. Dyspnea is attributed to restricted diaphragmatic excursion.

On examination, there is dullness to percussion and decreased breath sounds over the area of effusion. Hypoxia is frequently absent or late in onset with large volume accumulation.2 In older patients, empyema can present as fatigue, weight loss, and failure to thrive.2 The complete list of pleural effusion causes is extensive, but considering the patient's medical history and physical examination can narrow down the possible causes and guide workup (Table 2).4

| Signs and symptoms | Suggested etiology |

|---|---|

| Ascites | Cirrhosis |

| Distended neck veins | Heart failure, pericarditis |

| Dyspnea on exertion | Heart failure |

| Fever | Abdominal abscess, empyema, malignancy, pneumonia, tuberculosis |

| Hemoptysis | Malignancy, pulmonary embolism, tuberculosis |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | Malignancy |

| Lymphadenopathy | Malignancy |

| Orthopnea | Heart failure, pericarditis |

| Peripheral edema | Heart failure |

| S3 gallop | Heart failure |

| Unilateral lower extremity swelling | Pulmonary embolism |

| Weight loss | Malignancy, tuberculosis |

Chest Imaging

RADIOGRAPHY

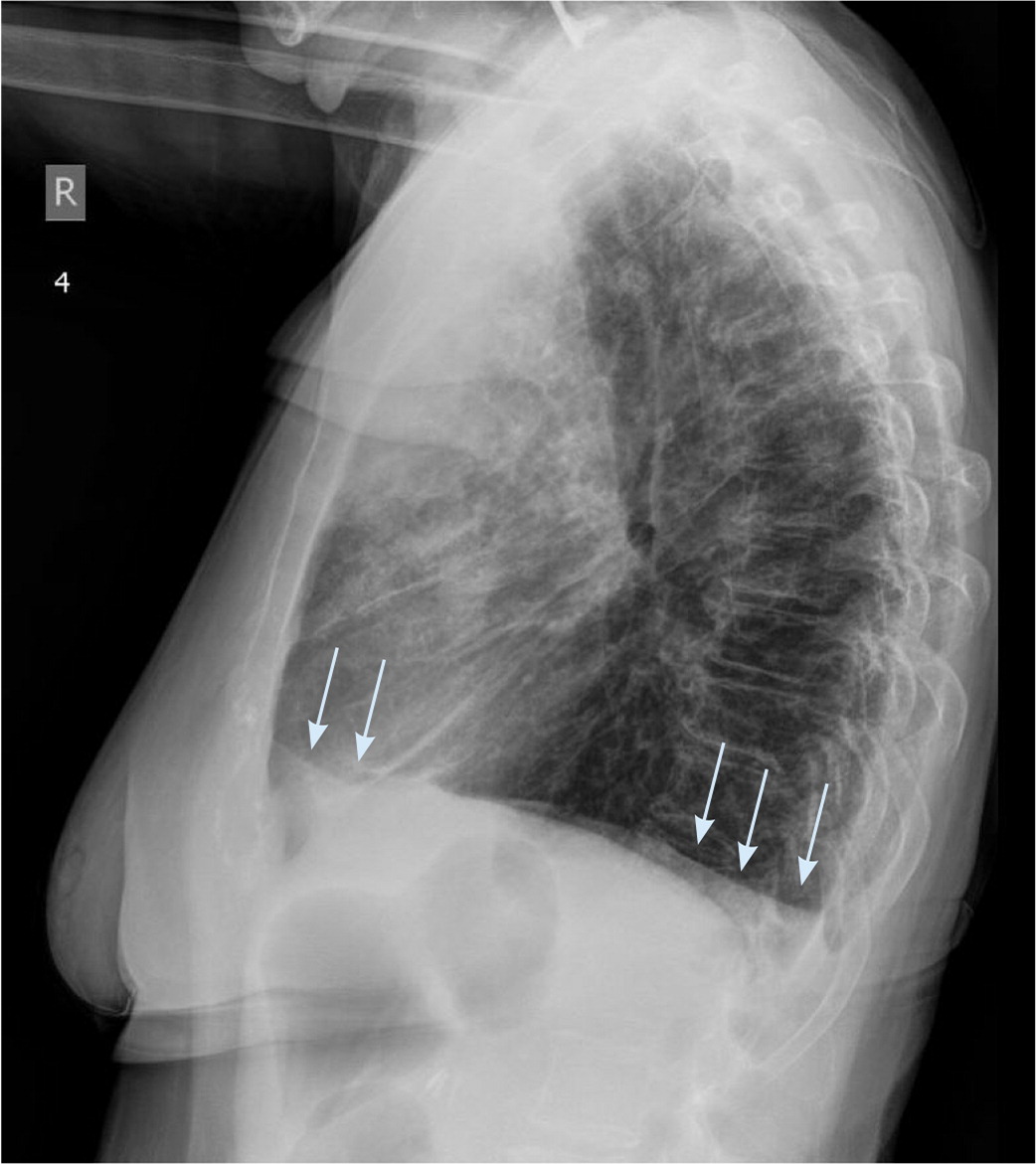

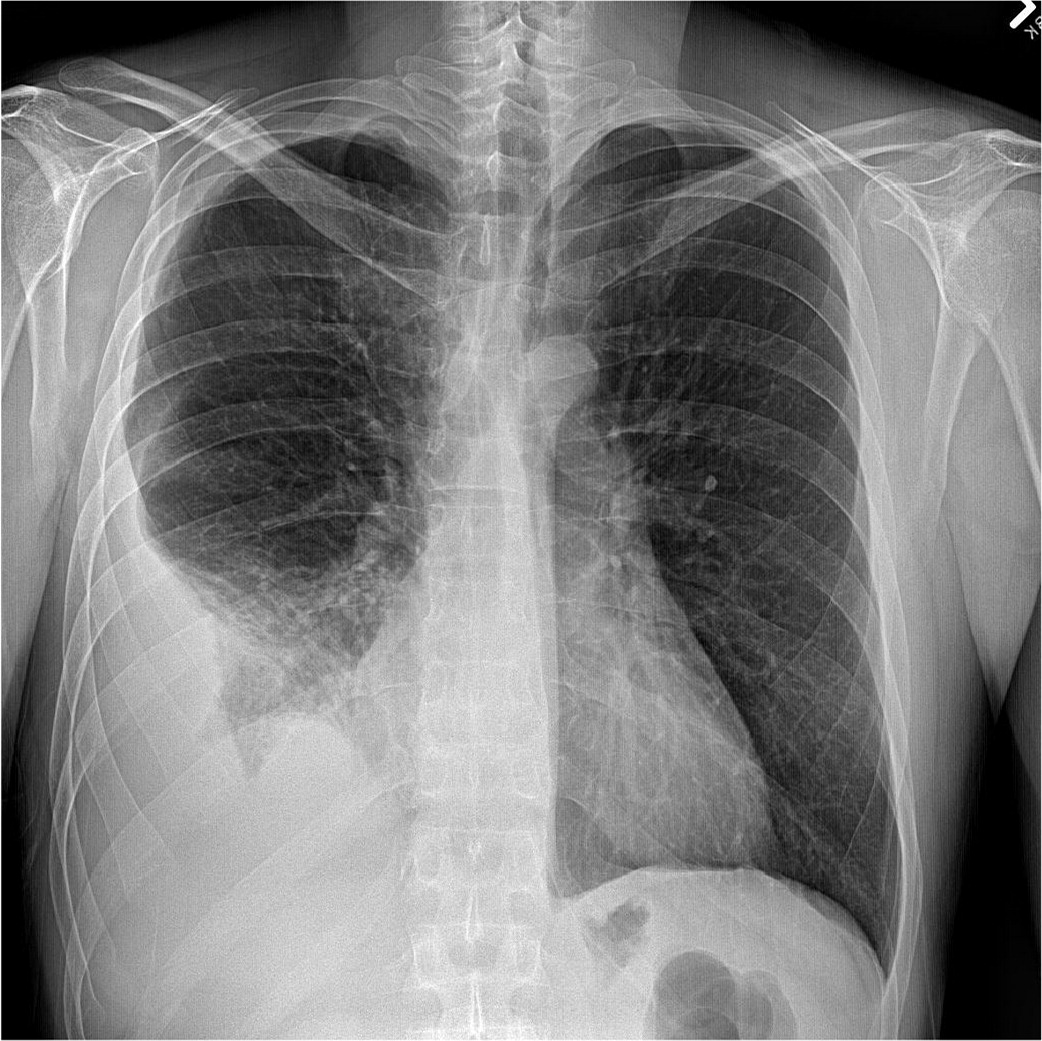

Chest radiography is the most common initial imaging modality used to diagnose pleural effusion. It reliably rules out large effusions and is helpful in determining whether an effusion is unilateral or bilateral. Sensitivity varies widely depending on the view. An effusion is undetectable on a posteroanterior film until it is at least 200 mL, whereas a lateral upright film detects effusions as small as 50 mL.5 The lateral decubitus film is the most sensitive, detecting minimal effusions as small as 10 to 25 mL, and it also indicates whether fluid is free-flowing or loculated.1,4 A supine antero-posterior film can hide large amounts of effusion, making it a poor diagnostic choice. Raising the head of the patient's bed to the semi-upright position improves the anteroposterior film sensitivity.5 Lower lobe consolidation makes diagnosis more difficult, and chest radiography cannot differentiate between transudates and exudates.14,15 Signs of pleural effusion on radiography first appear as thickening of the pleural fissures and blunting of the costophrenic angle (Figure 1). With moderate effusions, the diaphragm appears hazy and obscured, progressing to the presence of an air-fluid meniscus in large effusions (Figure 2). In massive effusions, there is dense opacification of the hemithorax and mediastinal shift.14

ULTRASONOGRAPHY

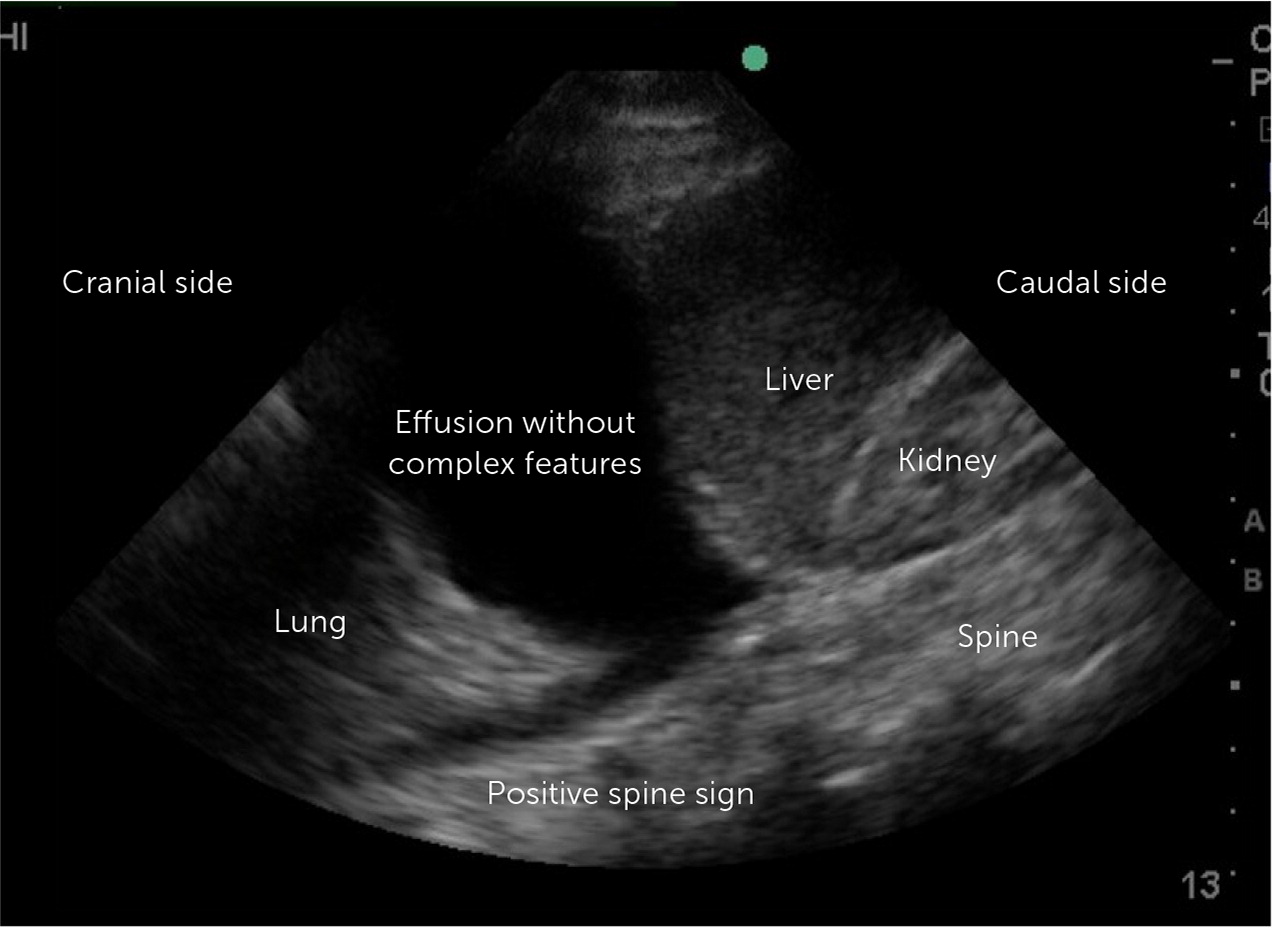

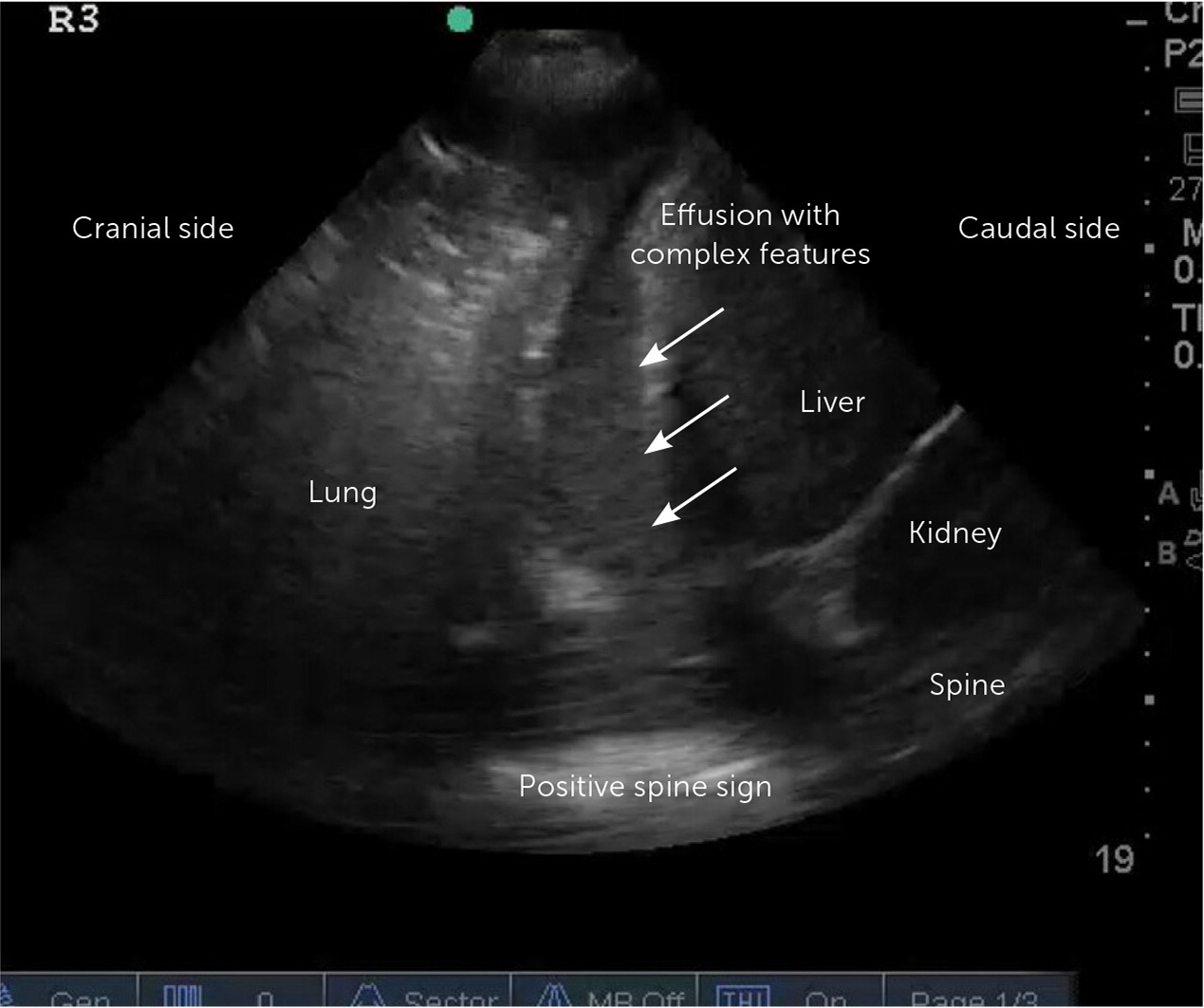

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) and thoracic ultrasonography are sensitive to small amounts of pleural effusion (those as small as 20 mL),16 characterize effusions, and provide guidance during pleural procedures. For these reasons, the British Thoracic Society recommends early usage of bedside ultrasound in the evaluation and management of pleural effusion.2,16,17 The American Association for Thoracic Surgery recommends using thoracic ultrasonography in addition to chest radiography in the evaluation of pleural effusion in the setting of infection.18 POCUS outperforms chest radiography in differentiating the presence of effusion (Figure 3) from consolidation15,19 and detects septations with greater sensitivity than computed tomography (CT).5 POCUS can identify complex para-pneumonic effusions with findings such as echogenic fluid (Figure 4), septations, and loculations (Figure 5). It can also identify signs of malignancy, such as pleural thickening and nodularity. Treatment of complicated parapneumonic effusions (i.e., infection of the pleural space) and empyema is time sensitive. Early detection warrants escalation of care and specialty consultation.8,16,19,20 Current barriers to routine use of thoracic ultrasonography in evaluating pleural disease include inconsistent availability and lack of operator training and experience.21,22

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

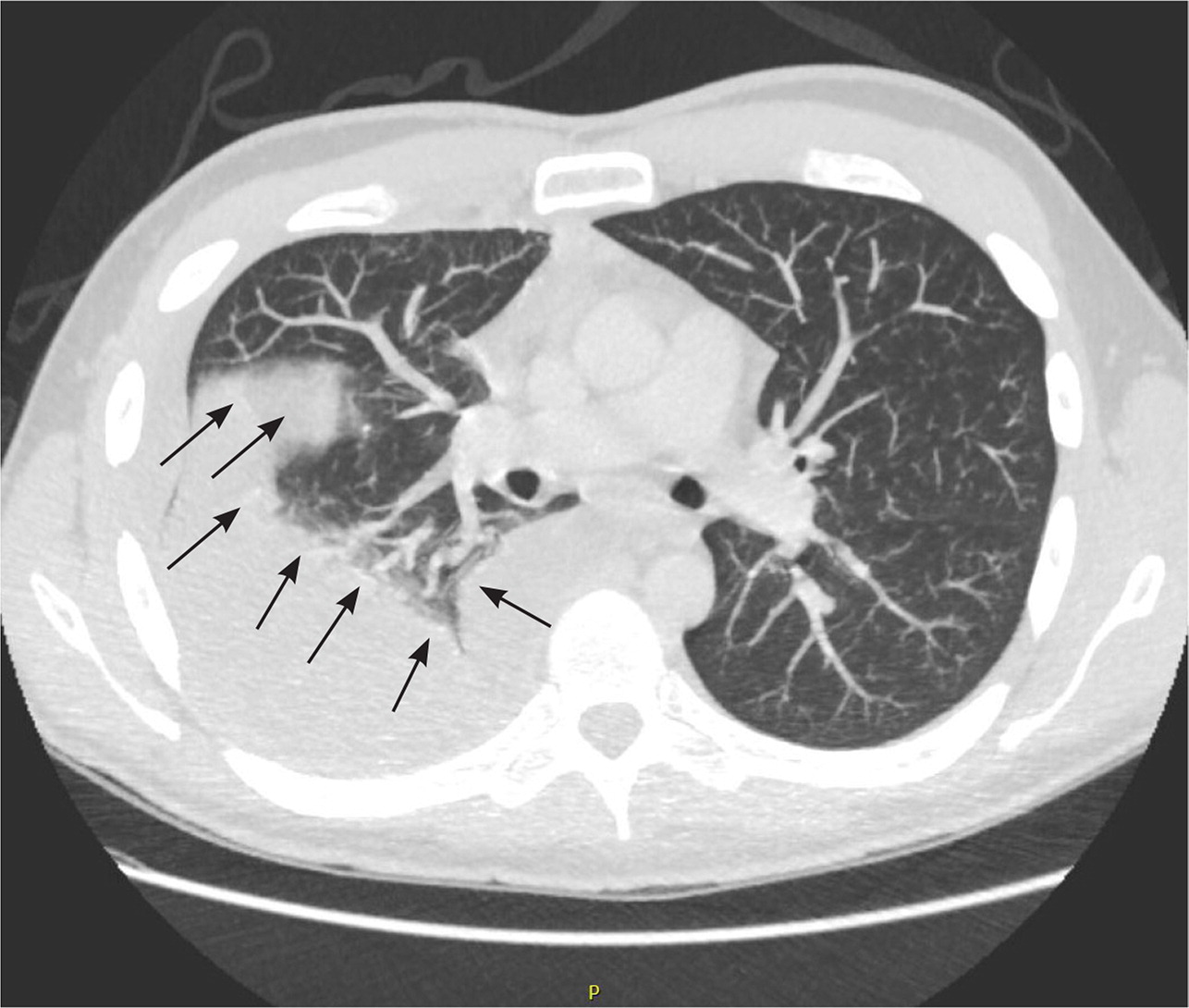

Chest CT is helpful in determining the size and location of an effusion and can exclude other causes of dyspnea (e.g., pulmonary embolism, mediastinal disease, esophageal rupture). If malignancy is suspected, further evaluation with CT is indicated. However, a negative CT result does not exclude malignancy.17 In patients with known malignancy, extending CT to the abdomen and pelvis can help identify a primary source and metastasis.5,22 The American College of Radiology grades chest CT with or without contrast as usually appropriate in the evaluation of suspected pleural disease.23 If malignancy is suspected, CT with contrast may detect pleural thickening and nodularity but has poor sensitivity (36% to 68%) and better specificity (78% to 94%).5,22 CT-guided or video-directed pleural biopsy can make the diagnosis definitive. Pleural fluid attenuation on CT cannot distinguish exudate from transudate. CT findings of lenticular effusion, loculation, and pleural thickening are associated with complicated parapneumonic effusions18 (Figure 6).

Thoracentesis

INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Diagnostic thoracentesis can help determine the cause of pleural effusion, and therapeutic drainage provides symptomatic relief. Thoracentesis is warranted for cases where the suspected cause is not heart disease, kidney failure, or liver failure (e.g., those presenting with fever and pleuritic chest pain or those with unilateral or disparate effusion sizes), or cases that do not improve after diuresis, dialysis, or treatment of the underlying disease.5 Heart failure is estimated to cause 36% of all effusions,24 and patients with small bilateral, right-greater-than-left effusions and high pretest probability for effusion due to heart failure do not need diagnostic thoracentesis (Figure 71,5,12,18,25,26). Minimal parapneumonic effusions can be treated conservatively with antibiotics and close monitoring.25

Traditional teaching recommends diagnostic thoracentesis for new-onset unilateral effusions greater than 1 cm on lateral decubitus radiography or those greater than 2 cm on ultrasonography and CT.1,8,18 Relative contraindications to thoracentesis include skin infection at the insertion site and uncorrected severe bleeding diathesis.27–29 Effusions that are too small (less than 1 cm) or loculated on POCUS or CT may require an interventional radiology or thoracoscopy approach. Bleeding risk may be reduced with ultrasound guidance by using direct visualization to decrease solid organ injury and avoid intercostal vessels.27,28 Decisions about the reversal of coagulopathies should be individualized based on urgency.29,30

PROCEDURAL BASICS

The physician should obtain consent and inform patients about the potential complications of an unsuccessful procedure, which include pain, pneumothorax, hemorrhage, or solid organ injury. Bilateral thoracentesis is not recommended.

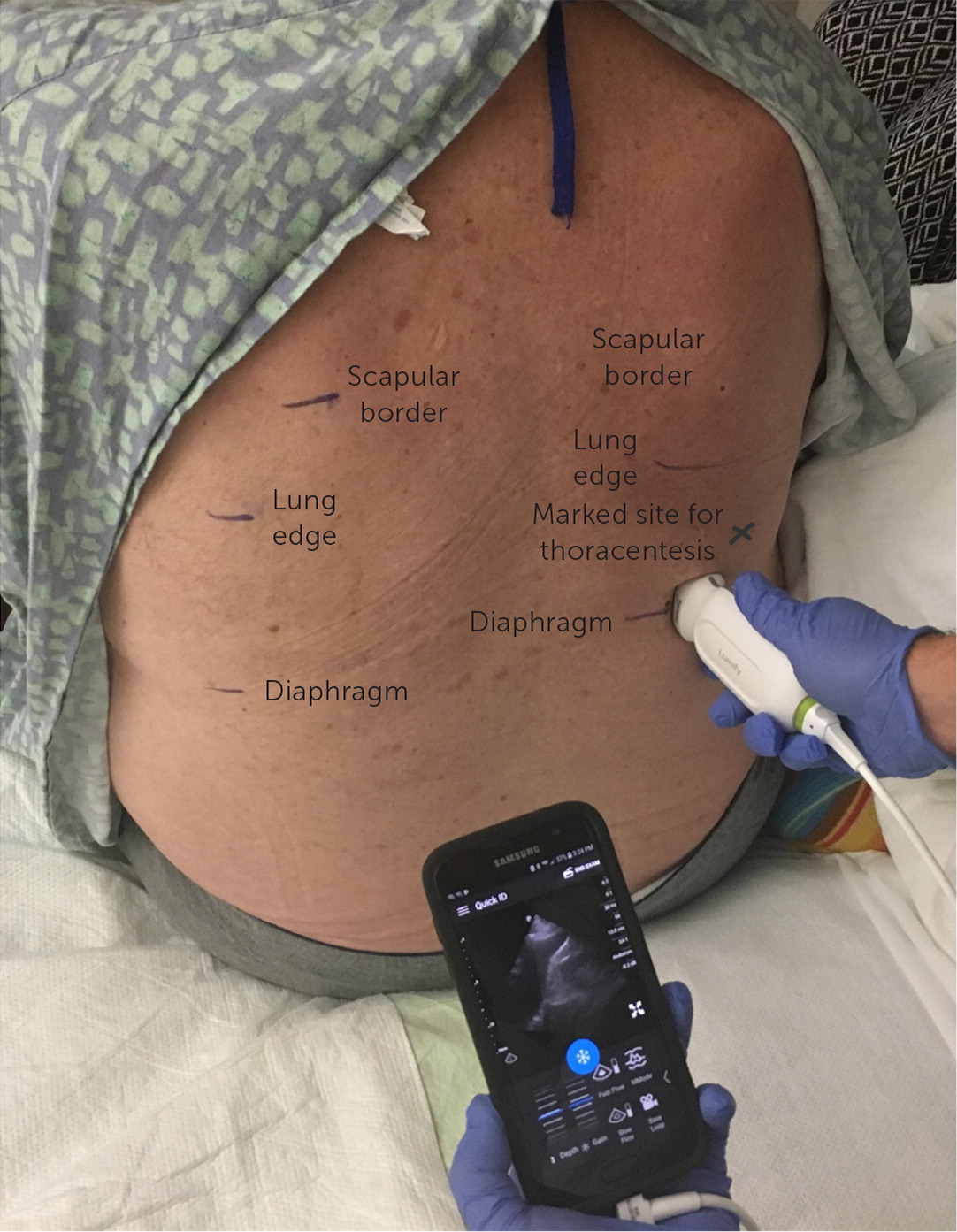

The patient may be positioned supine or seated upright. A low-frequency ultrasound probe is used to identify the diaphragm inferiorly and the edge of the lung cranially, noting the height of the effusion (Figure 8). The insertion site is marked no closer than 5 to 10 cm from the spine and one to two intercostal spaces above the diaphragm.31 The needle should not be inserted below the ninth rib, which avoids the diaphragm.32 After site marking, local anesthesia is administered superior to the rib, avoiding the inferior surface and the neurovascular bundle. A diagnostic sample can be aspirated with a fine-bore needle and a 50-mL syringe.5 For therapeutic drainage, a large-bore, over-the-needle catheter is inserted perpendicular to the chest wall. The catheter is guided over the needle, and the needle is removed before aspiration begins.31,32 In therapeutic thoracentesis, up to 1.5 L can be drained. Aspiration volumes greater than 1.5 L may be associated with an increased risk for reexpansion pulmonary edema.33 After the procedure, the patient should be monitored for post-procedural pneumothorax, bleeding, and reaccumulation. Routine chest radiography is not required unless the patient is symptomatic, air is aspirated, or multiple thoracentesis attempts were performed.2,28,31,34 Videos demonstrating the procedure are available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ivTyH09BcHg and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lUAn_1R7V3E.

ULTRASOUND GUIDANCE

The Society of Hospital Medicine,11 American Thoracic Society,26 and the British Thoracic Society5,17 recommend that all pleural procedures be ultrasound guided based on evidence demonstrating safety, increased success, and relative absence of harm. Compared with percussion to identify effusion borders, ultrasound guidance is associated with fewer complications, including solid organ puncture, pneumothorax, and unsuccessful procedure.5,11,17,18,26,28,33,35 Outcomes with static guidance, where patients are marked using ultrasonography at the bedside before thoracentesis, are similar to those with live guidance, in which needle entry is actively visualized.11,34 Live guidance requires additional sterile preparation and additional operator experience but is selectively useful for smaller or loculated effusions.

Fluid Analysis

Fluid analysis begins with evaluation of aspirate appearance and odor (Table 34,5). Light's criteria can help differentiate exudates from transudates36–38 (Table 42,5,17,36,39,40). It is nearly 100% sensitive for exudates but is less specific because 20% of patients with heart failure after receiving diuretics have fluid ratios consistent with exudate. Elevated serum N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide indicates heart failure as the cause of pleural effusion.38,40,41 Pleural aspirate should routinely be tested using Gram stain, cell count with differential, culture, cytology, and protein, l-lactate dehydrogenase, and pH levels. Serum protein and l-lactate dehydrogenase should be assayed at the same time. In the setting of infection in the absence of purulence, testing for a glucose level less than 40 mg per dL (2.22 mmol per L) and pH less than 7.2 is helpful for diagnosing complicated parapneumonic effusion because cultures are slow to return and have low sensitivity.18 In high prevalence areas, initial testing may include tuberculosis testing (i.e., acid-fast bacillus, Mycobacterium culture, and adenosine deaminase) because it requires special cultures5,6,24 (Table 51,5,17,18,40,41). Additional testing should be based on clinical suspicion.1,5,31

| Pleural fluid appearance | Potential etiology |

|---|---|

| Anchovy brown fluid | Ruptured amoebic abscess |

| Bile stained | Chylothorax (e.g., biliary fistula) |

| Black | Aspergillus infection |

| Bloody | Benign asbestos, malignancy, post–cardiac injury syndrome, pulmonary embolism, trauma |

| Containing food particles | Esophageal perforation |

| Milky | Chylothorax or pseudochylothorax |

| Serous | Nonspecific, heart failure, liver disease |

| Turbid with foul odor | Anaerobic empyema |

| Urine; may have ammonia odor | Urinothorax |

| Test | Criteria | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Protein | 1. Pleural/serum protein ratio > 0.5 | Light's criteria* is positive for exudative fluid when 1 of 3 criteria is met2,5,36 |

| LDH | 2. Pleural/serum LDH ratio > 0.6 3. Pleural LDH > two-thirds of upper limit of normal serum LDH range | |

| Cell count with differential | Neutrophil predominant | Indicates acute parapneumonic effusion, pulmonary embolism, and benign asbestos5 |

| Lymphocyte predominant | Indicates long-standing effusions caused by malignancy, heart failure, long-standing tuberculosis, lymphoma, rheumatoid pleurisy, sarcoidosis, or late post coronary artery bypass grafting5 | |

| Culture and Gram stain | Positive | Culture has low sensitivity (56%),39 but a positive culture result is diagnostic for bacterial parapneumonic effusion; inoculating blood culture bottles (anaerobic and aerobic) at the bedside increases positivity rate5 |

| Cytology | Presence of atypical cells | Send as much aspirate volume as available, with a goal of 50 to 60 mL; most common causes of secondary pleural malignancies are lung and breast cancer, and other common primary cancers are lymphoma, gastrointestinal, and ovarian; mesothelioma is a common cause with low cytology sensitivity; overall, cytology has a poor sensitivity of 60% 17,40; pleural biopsy is diagnostic |

| pH | Level < 7.2† | When arterial blood gas kit is available, test for aspirates with concern for infection that are not obviously purulent; pH < 7.2 is consistent with complicated effusion; if purulence is present, do not test for pH—the diagnosis is empyema5 |

| Concern/indication | Further testing | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Bloodstained fluid | Pleural red blood cell count > 100,000 per mm3 | Fluid hematocrit > 1% is diagnostic for malignancy, trauma (including recent cardiac surgery), pneumonia, and pulmonary embolism1 |

| Bloody aspirate, trauma | Pleural hematocrit > 50% of the peripheral hematocrit | Indicates hemothorax1 |

| Clinical infection, concurrent pneumonia, empyema, tuberculosis | Pleural glucose level < 40 mg per dL (2.22 mmol per L) | Useful when pH test is not reliable, or not available; may warrant earlier and more invasive methods of drainage 18; low glucose can also indicate advanced malignancy, rheumatoid effusions, and esophageal rupture5 |

| Esophageal rupture or acute pancreatitis/pancreatic pseudocyst | Pleural fluid amylase level | Food particles can be found with esophageal rupture and are a surgical emergency; amylase is also elevated in tuberculosis and malignancy, especially adenocarcinoma and ruptured ectopic pregnancy5; serum lipase is sensitive for pancreatitis |

| Heart failure (when misclassified as exudates by Light's criteria) | Serum NT-proBNP thresholds for acute heart failure, which are adjusted for age Pleural NT-proBNP level > 1,500 pg per mL or Serum-pleural albumin gradient > 1.2 g per dL (12 g per L) or Serum-pleural protein gradient > 3.1 g per dL (31 g per L) | NT-proBNP is more sensitive for heart failure than protein or albumin gradient41; serum NT-proBNP values are comparable with pleural assay values in predicting heart failure and are less costly40 |

| Malignancy | Cytology Serum/pleural mesothelin and other tumor markers (e.g., CEA, CA 125, CA 15-3) | Cytology is positive in 60% of malignant pleural effusions1 Consider serum/pleural mesothelin in concerning cytology, but not for screening; tumor markers have low sensitivity and are not recommended for routine testing; imaging-guided pleural biopsy is recommended5; thoracoscopy is diagnostic in 90% of patients with negative cytology1 |

| Milky appearance of fluid | Pleural fluid triglyceride and cholesterol levels | Chylothoraxes (triglycerides > 110 mg per dL [1.24 mmol per L] with low cholesterol on fluid assay) in thoracic duct injury Pseudochylothorax (cholesterol > 250 mg per dL [6.47 mmol per L] on fluid assay) in chronic rheumatoid effusion and tuberculosis5 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus pleuritis) and small bilateral effusion | Pleural ANA17 | High pleural-serum ANA ratio is sensitive for lupus pleuritis17; however, it may be elevated due to malignancy and infection5 |

| Tuberculosis (lymphocyte predominant) in high-prevalence populations | Pleural ADA, pleural IGRA, pleural Mycobacterium cultures, pleural AFB | Pleural ADA testing is 91% sensitive and 88% specific (false positives in the setting of empyema, rheumatoid pleurisy); IGRA is 95% sensitive and 96% specific17; AFB sensitivity < 5%, Mycobacterium cultures are 10% to 20% sensitive; pleural biopsy is definitive when tuberculosis is cultured or PCR positive; cell count is lymphocytic in tuberculosis5 |

Empyema and Parapneumonic Effusions

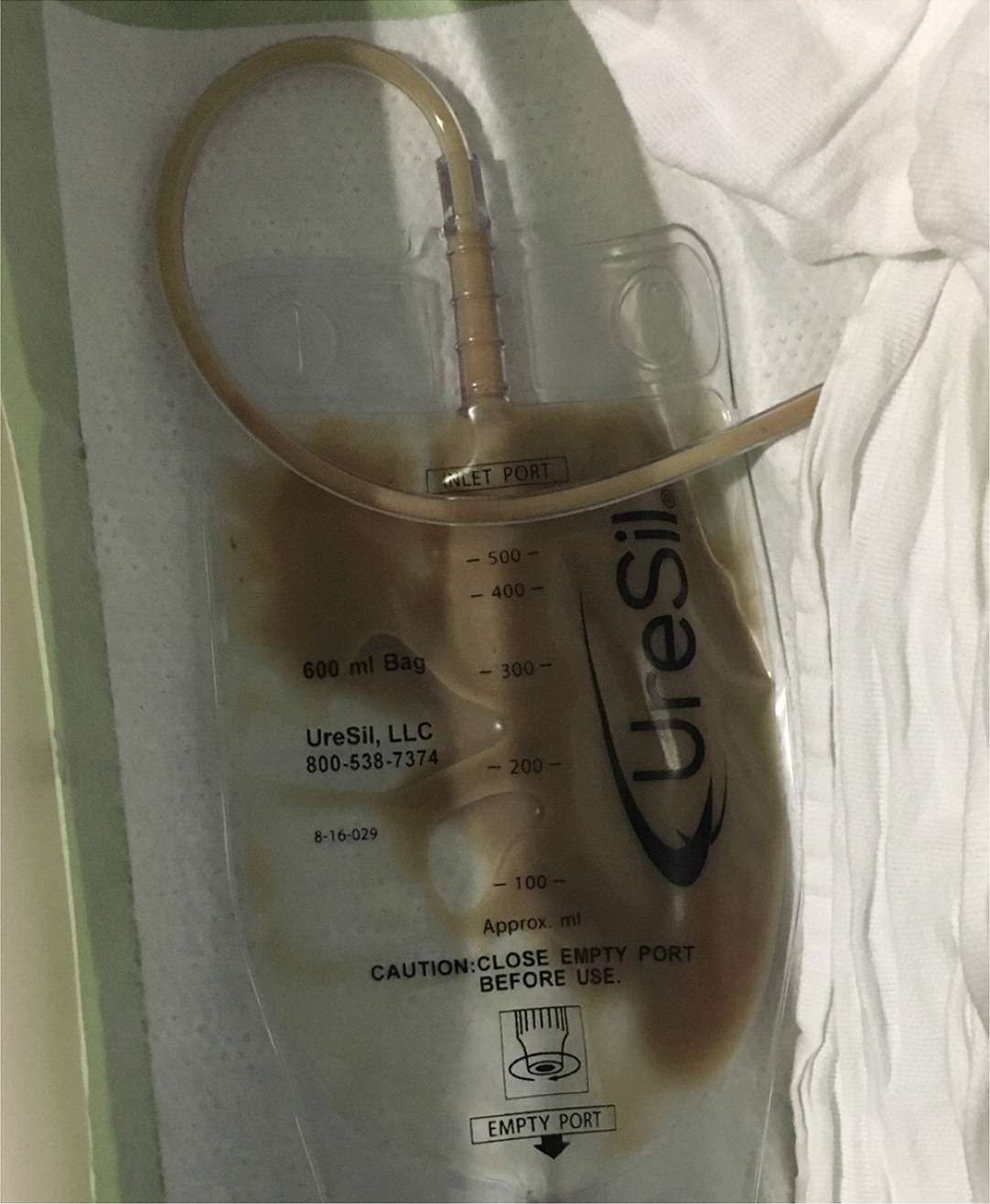

Parapneumonic effusion (pleural effusion associated with pneumonia or lung abscess) and empyema (aspiration with purulence [Figure 9]) are the most common causes of exudates and are rising in incidence in the United States.2 Parapneumonic effusions are found in 20% to 40% of hospitalized patients with pneumonia and up to 62% of patients with pneumonia in the intensive care unit.42 Complicated effusions can be associated with small volumes; therefore, size alone cannot rule out the need for thoracentesis. Early POCUS of the pleura can detect complex effusions by demonstrating echogenic fluid, septations, and loculations. However, anechoic fluid that appears to be a simple effusion does not rule out culture-positive effusions.20 Given the potential for an effusion to become complicated within days if treatment is delayed, it is important for primary care physicians to recognize and treat effusions appropriately and promptly8 (Table 68,17,18,25,42–44).

| Parapneumonic effusion | Imaging characteristics | Aspirate characteristics | Therapy overview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimal | Lateral anterior chest radiography with costophrenic angle blunting, minimal size on POCUS or CT (estimated < 100 mL, < 10 mm fluid in height on lateral decubitus film) | Unknown | Thoracentesis usually not indicated; antibiotic therapy with close monitoring |

| Simple | Effusion without complex features on POCUS or CT (free-flowing and without septations or loculations); often a small, unilateral effusion (estimated size 100 mL, > 20 mm in height on CT or POCUS, > 10 mm on lateral decubitus film) | Gram negative, culture negative, pH > 7.2, and glucose > 60 mg per dL (3.33 mmol per L) | Thoracentesis is indicated; medical management with antibiotics; monitoring for exacerbations, increasing effusion size, and new complex features on repeat imaging |

| Complicated | Variable in size—any large (more than one-half of the hemithorax on chest radiography) effusion is suspect; septations and loculations on POCUS; loculation and thickened parietal pleura on contrast CT; absence of these findings on imaging does not rule out a complicated parapneumonic effusion | Gram positive, culture positive, or pH < 7.2; glucose < 40 mg per dL (2.22 mmol per L), or purulence on initial aspirate (empyema) | Thoracentesis plus catheter or chest tube drainage; tissue plasminogen activator/deoxyribonuclease therapy; medical thoracoscopy and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for decortication; expanded antibiotic coverage and duration |

To address parapneumonic effusions, the underlying pneumonia must be treated. This generally includes antibiotics chosen based on prevalent community- or hospital-acquired causes. Anaerobic coverage with metronidazole (Flagyl) is warranted for treatment of complicated effusions39 (Table 739,43). Antibiotics should not be delayed for pleural analysis unless the patient is clinically stable with an indolent infection. Simple parapneumonic effusions will often resolve with antibiotics alone. Complicated parapneumonic effusions and empyema require more invasive methods of drainage with catheter or chest tube. Experts estimate 30% of patients may require further surgical intervention with medical thoracoscopy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery.18,43 Patients who are good surgical candidates may benefit from earlier video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Patients with a high risk of mortality may benefit from combined tissue plasminogen activator/deoxyribonuclease administered via chest tube.44 A five or greater RAPID (renal, age, purulence, infection source, and dietary factors) score predicts a high three-month mortality risk45 (https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/4014/rapid-score-pleural-infection).

| Community-acquired infection | Hospital-acquired infection | |

|---|---|---|

| Target species | Anaerobes, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Viridans streptococci | Anaerobes and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas, Enterobacter |

| Antibiotics | Metronidazole (Flagyl) plus ceftriaxone or Ampicillin-sulbactam or Metronidazole plus fluoroquinolone or Carbapenem | Metronidazole, vancomycin, and cefepime or Piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn) and vancomycin or Metronidazole, vancomycin, and ciprofloxacin or Carbapenem and vancomycin |

Malignant Pleural Effusion

Malignant pleural effusion is another common cause of exudates in the United States. Recurrent malignant pleural effusions have an overall poor prognosis, with an average survival of four to seven months.26 The American Thoracic Society has an evidence-based guideline on treating malignant effusions and recommends individualized treatment with an indwelling pleural catheter or talc pleurodesis in symptomatic patients.26

Referral

Specialist consultation is recommended if assistance with the initial thoracentesis is needed, for a suspected exudative effusion, or for a complicated effusion with loculations on imaging. Referral is also warranted if pleural effusion attributed to a transudative process does not resolve after treatment or if the diagnosis is still unknown after the initial aspirate analysis. Complicated parapneumonic effusion, empyema, and malignant effusion warrant consultation for catheter or chest tube drainage, evaluation for pleurodesis, indwelling pleural catheter placement, or thoracoscopy. Repeat imaging should be performed several days after treatment to check for improvement. Repeated evaluations are recommended for patients with reaccumulating fluid or clinical decline.4

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Saguil, et al.4 and Porcel and Light.1

Data Sources: PubMed searches were completed using the key terms pleural effusion, pleural fluid analysis, pleural tap, and thoracentesis. The searches included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, review articles, and practice guidelines. The Cochrane database and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: January 2022 to July 2022.

The authors thank Mike Wagner, MD, and Julia Cupp, MD, for their editorial assistance with this manuscript.