Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(5):476-486

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Hyponatremia and hypernatremia are electrolyte disorders that can be associated with poor outcomes. Hyponatremia is considered mild when the sodium concentration is 130 to 134 mEq per L, moderate when 125 to 129 mEq per L, and severe when less than 125 mEq per L. Mild symptoms include nausea, vomiting, weakness, headache, and mild neurocognitive deficits. Severe symptoms of hyponatremia include delirium, confusion, impaired consciousness, ataxia, seizures, and, rarely, brain herniation and death. Patients with a sodium concentration of less than 125 mEq per L and severe symptoms require emergency infusions with 3% hypertonic saline. Using calculators to guide fluid replacement helps avoid overly rapid correction of sodium concentration, which can cause osmotic demyelination syndrome. Physicians should identify the cause of a patient's hyponatremia, if possible; however, treatment should not be delayed while a diagnosis is pursued. Common causes include certain medications, excessive alcohol consumption, very low-salt diets, and excessive free water intake during exercise. Management to correct sodium concentration is based on whether the patient is hypovolemic, euvolemic, or hypervolemic. Hypovolemic hyponatremia is treated with normal saline infusions. Treating euvolemic hyponatremia includes restricting free water consumption or using salt tablets or intravenous vaptans. Hypervolemic hyponatremia is treated primarily by managing the underlying cause (e.g., heart failure, cirrhosis) and free water restriction. Hypernatremia is less common than hyponatremia. Mild hypernatremia is often caused by dehydration resulting from an impaired thirst mechanism or lack of access to water; however, other causes, such as diabetes insipidus, are possible. Treatment starts with addressing the underlying etiology and correcting the fluid deficit. When sodium is severely elevated, patients are symptomatic, or intravenous fluids are required, hypotonic fluid replacement is necessary.

Sodium abnormalities are common electrolyte disorders associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Abnormalities include hyponatremia (serum sodium concentration less than 135 mEq per L) and the less common hypernatremia (greater than 145 Eq per L). Understanding the pathophysiology of these conditions can be helpful in diagnosis and treatment.

Pathophysiology

Osmolarity is the concentration of solutes (primarily sodium) in a body fluid. Water easily moves through cell membranes, whereas sodium ions do not. Water moves through cell membranes from lower sodium concentration areas to higher sodium concentration areas to achieve equal osmolarity inside and outside cells. If the extracellular sodium concentration exceeds the intracellular sodium concentration, water moves from within cells into the extracellular space, causing cell shrinkage. Conversely, if extracellular sodium concentration is too low, water moves from the extracellular space into cells, causing cellular swelling.

The body uses compensatory mechanisms to maintain sodium concentration to prevent cell shrinkage or swelling. One key mechanism is the changing levels of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the hypothalamus in response to changing sodium concentration in plasma.

In hypernatremia, increased ADH secretion stimulates water reabsorption by the kidneys. The resulting water retention lowers serum sodium concentration. Conversely, in hyponatremia, the suppression of ADH secretion results in excretion of free water by the kidneys. This loss of free water increases serum sodium concentration. Factors such as kidney disease or taking certain medications (e.g., diuretics) can limit the kidneys' ability to dilute or concentrate urine in response to ADH levels.1

Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia is categorized as mild (130 to 134 mEq per L), moderate (125 to 129 mEq per L), or severe (less than 125 mEq per L).2 Hyponatremia is treated as acute when occurring within 48 hours and as chronic when occurring over 48 hours or more or when the duration is unknown.

PREVALENCE

Additionally, in outpatient settings, chronic hyponatremia is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, cancer (lung, head, and neck), gait instability, osteoporosis, falls, and fractures.4–8 These risks are more pronounced in older adults.3,5 Approximately 28% of hospitalized patients have hyponatremia, which is associated with increased length of hospitalization, higher costs, and a twofold increase in mortality.9

SYMPTOMS

Mild symptoms include nausea, vomiting, weakness, headache, and mild neurocognitive deficits. Severe symptoms of acute hyponatremia include delirium, confusion, impaired consciousness, ataxia, seizures, and, rarely, brain herniation and death due to rapid water shifts from extracellular tissues into the brain. In chronic hyponatremia, mildly and moderately depressed sodium concentration may be asymptomatic.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

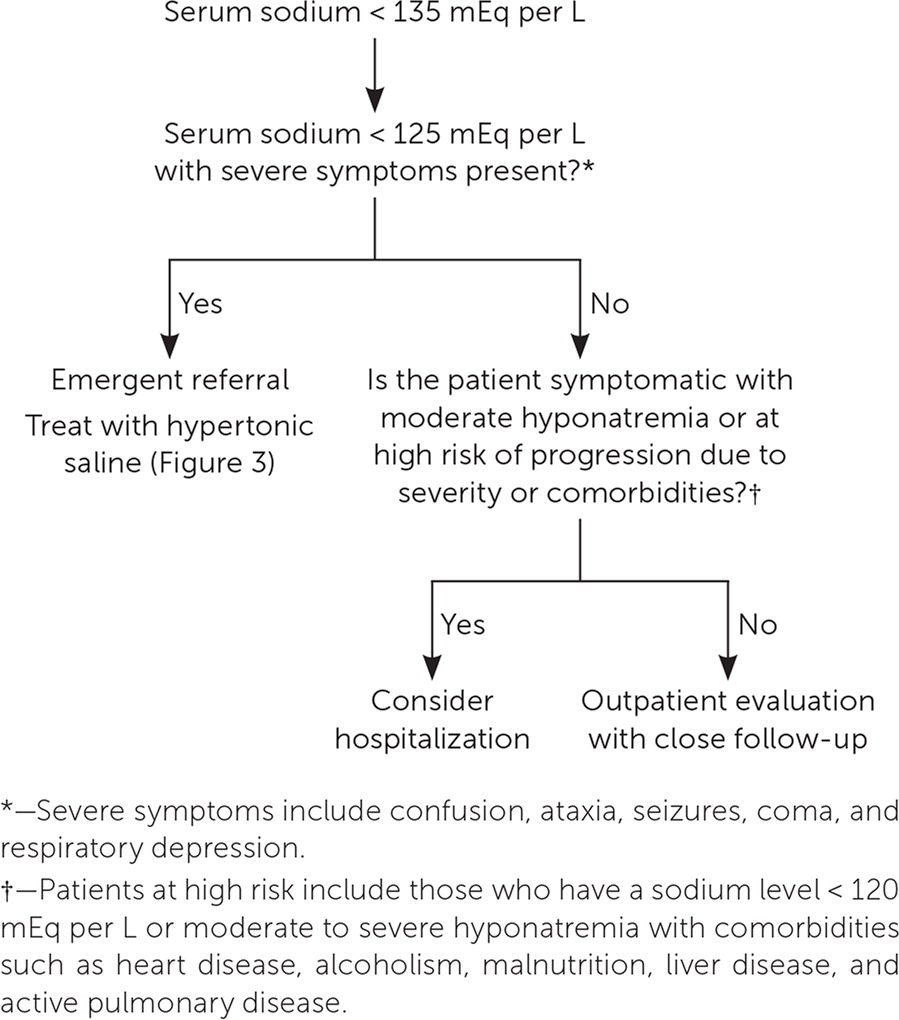

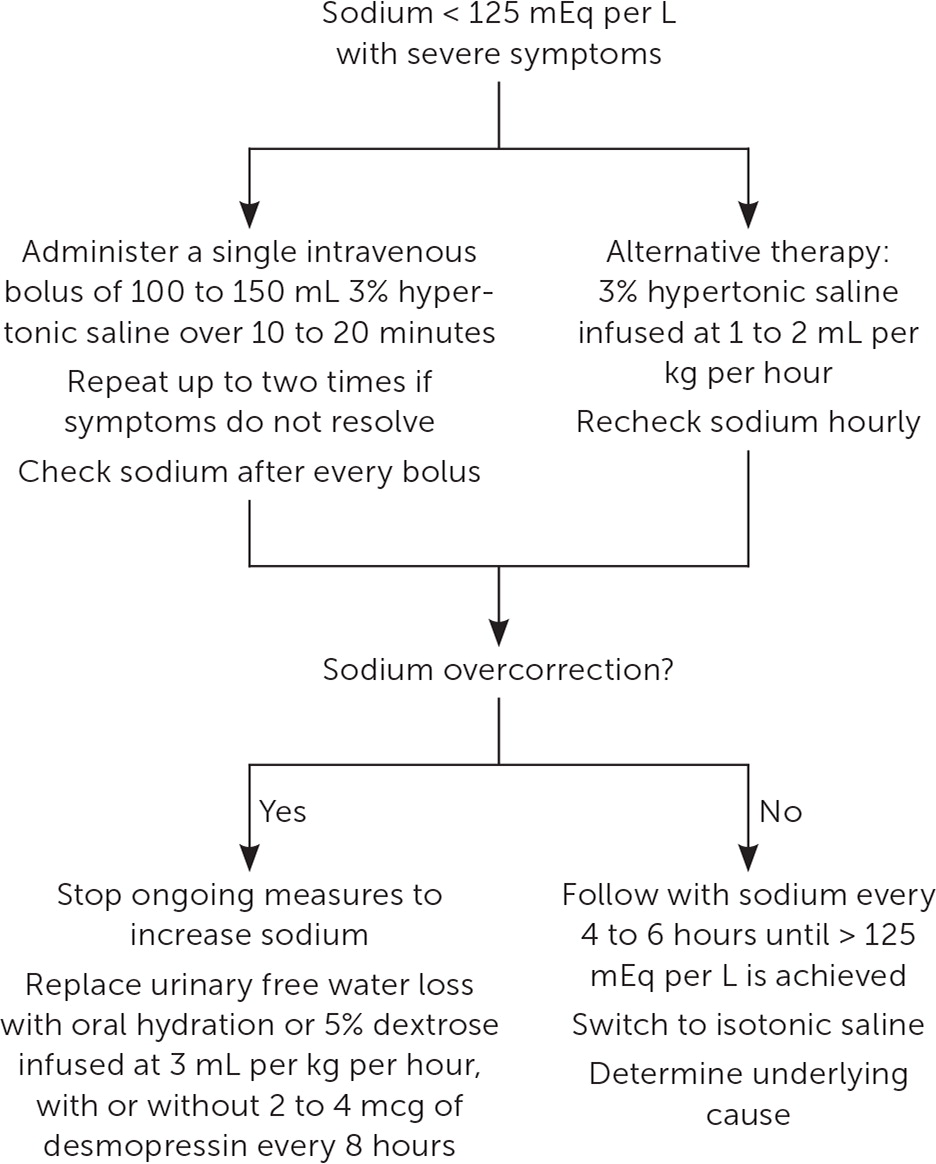

The patient's symptoms and sodium concentration guide the initial assessment. A sodium concentration of less than 125 mEq per L with severe symptoms requires emergency intervention with 3% hypertonic saline infusion.2,10 Hospitalization should be considered when the sodium concentration is less than 125 mEq per L and symptoms are present, or in high-risk patients with moderate to severe hyponatremia. High-risk patients have a sodium concentration of less than 120 mEq per L or comorbidities such as heart disease, alcoholism, malnutrition, liver disease, and active pulmonary disease. Figure 1 provides guidelines for the initial assessment of hyponatremia.2,10

HISTORY

The medical history can identify potential causes of hyponatremia. Many commonly prescribed medications can cause hyponatremia (Table 111). The history can also identify other possible causes, including excessive alcohol consumption, use of illicit drugs (e.g., ecstasy), diets with very low solute intake (e.g., tea and toast diet), and prolonged exercise in which free water intake exceeds water loss from sweat (dilutional hyponatremia).2,12

| Hypovolemic hyponatremia |

| Loop diuretics |

| Thiazide diuretics |

| Euvolemic hyponatremia/syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion |

| Barbiturates |

| Carbamazepine |

| Clozapine (Clozaril) |

| Desmopressin |

| Narcotic medications (opioids) |

| Oxytocin |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| Tricyclic antidepressants |

| Vincristine |

LABORATORY TESTING

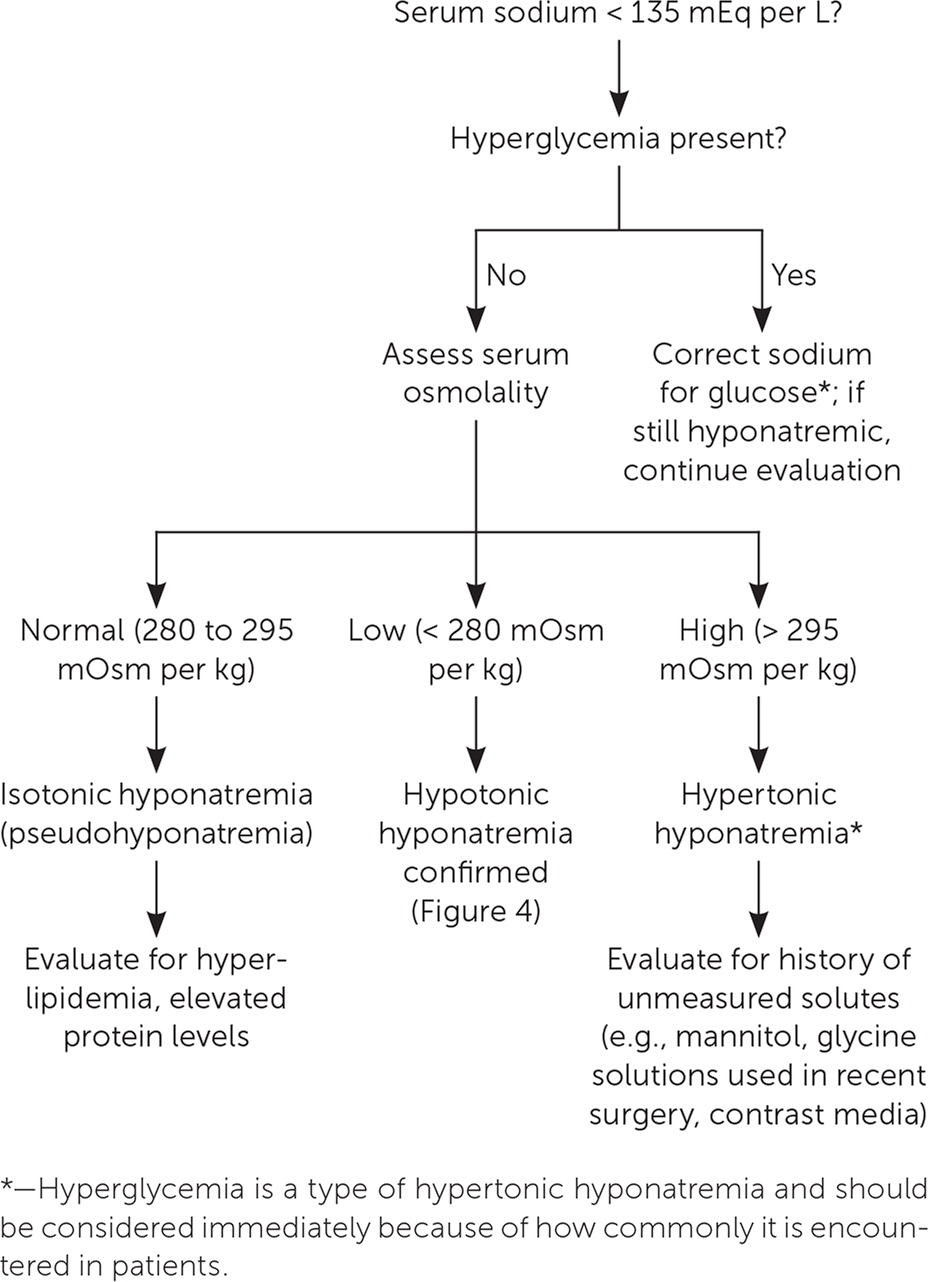

When the history does not identify a cause, laboratory testing can be helpful. Common initial tests include serum osmolality, a comprehensive metabolic profile, and urine screening for sodium, creatinine, and osmolality (Table 211). Serum osmolality can distinguish between isotonic, hypotonic, and hypertonic hyponatremia (Figure 211).

| Test | Considerations |

|---|---|

| Comprehensive metabolic panel | Hyperglycemia may suggest false low sodium (hypertonic hyponatremia) instead of true hypotonic hyponatremia Abnormal liver function test results may suggest liver dysfunction as a contributor Elevated creatinine or blood urea nitrogen helps determine volume status and may indicate a kidney-related etiology |

| Serum osmolality | Differentiates between true hypotonic hyponatremia and alternate etiologies |

| Urine screening (urine sodium, creatinine, osmolality) | Helps distinguish etiologies based on volume status |

If symptoms of specific comorbidities are present, additional testing may be necessary, such as obtaining B-type natriuretic peptide to evaluate for heart failure, thyroid-stimulating hormone for thyroid disease, and urine drug screening for suspected illicit drug use.

Other substances in the blood can result in a false low sodium concentration. This includes elevated levels of protein or triglycerides, which results in isotonic hyponatremia (i.e., pseudohyponatremia) or elevated glucose or exogenous substances (e.g., mannitol, contrast media) causing hypertonic hyponatremia.

SEVERE HYPONATREMIA

Guidelines recommend up to three 100-mL boluses of 3% saline administered at 10-minute intervals or 150 mL at 20-minute intervals, with an initial goal of increasing sodium by 4 to 6 mEq per L.1,2,10 Sodium concentration should be monitored after each hypertonic saline bolus and every six hours during the first 24 hours of treatment for severe symptomatic hypernatremia.1,2,10 Overly rapid sodium correction should be avoided because this may lead to osmotic demyelination syndrome (ODS), a rare but severe complication caused by the loss of myelin sheaths in brainstem axons.

One randomized controlled trial found that patients with a sodium concentration of less than 125 mEq per L and moderate or severe symptoms can be treated with bolus or continuous infusions. Both treatments have been shown to correct hyponatremia without an increased risk of ODS or mortality; however, bolus infusion improves sodium levels more quickly with less overcorrection.13

ODS is more likely when sodium concentration is less than 105 mEq per L. Other predisposing contributors to ODS include malnutrition, alcohol use, and hypokalemia.2,14 In patients with chronic hyponatremia (occurring over 48 hours or more) at increased risk of ODS, guidelines recommend limiting sodium correction to 8 mEq per L over 24 hours. For patients without risk factors, sodium correction should be limited to 12 mEq per L over 24 hours or 18 mEq per L over 48 hours to minimize the risk of ODS.2 Online calculators for determining optimal infusion rates are listed in Table 3.11

| Measurement | Calculator | Equations and comments |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium correction for hyperglycemia | https://www.mdcalc.com/sodium-correction-for-hyperglycemia | Measured sodium + 0.016 × (serum glucose − 100) Measured sodium + 0.024 × (serum glucose − 100)* |

| Serum osmolality | https://www.mdcalc.com/serum-osmolality-osmolarity | Serum osmolality = (sodium × 2) + (glucose ÷ 18) + (blood urea nitrogen ÷ 2.8) Normal osmolality = 280 to 295 mOsm per kg In patients with hyperglycemia, uncorrected sodium should be used to calculate osmolality |

| Sodium deficit | https://www.mdcalc.com/sodium-deficit-in-hyponatremia | Sodium deficit = total body water % × body weight (kg) × (desired sodium − actual sodium) For total body water %, use 0.6 for men and 0.5 for women |

| Infusion rate of sodium | https://www.mdcalc.com/sodium-correction-rate-hyponatremia-hypernatremia | Serum sodium correction should not proceed faster than 0.5 mEq per L per hour for the first 24 to 48 hours; however, in patients with severe symptoms, a rate of 1.0 to 2.0 mEq per L per hour is acceptable (these situations typically require use of 3% saline) The goal is to increase the serum sodium concentration by 6 to 8 mEq per L, not to exceed 10 to 12 mEq per L in the first 24 hours and 18 mEq per L in the first 48 hours |

| Free water deficit in hypernatremia | https://www.mdcalc.com/free-water-deficit-in-hypernatremia | 0.6 × body weight (kg) × [(serum sodium ÷ 140) − 1] Results of this formula are in liters Administer the total volume as free water over 24 hours using oral or enteral free water (preferred), or hypotonic fluids such as dextrose 5% in water |

| Fractional excretion of uric acid | https://www.scymed.com/en/smnxps/pspdj228.htm | Fractional excretion of uric acid = (urinary uric acid × serum creatinine) ÷ (serum uric acid × urine creatinine) Less than 0.1 suggests prerenal causes, while > 0.1 indicates syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion or renal etiologies |

Overcorrection of sodium in a patient whose initial serum level was less than 125 mEq per L should be aggressively managed (Figure 311). This includes stopping ongoing efforts to increase sodium and replacing urinary water losses with free water orally or dextrose 5% infused at 3 mL per kg per hour.2 Desmopressin (a synthetic analogue of ADH) infusion of 2 to 4 mcg every eight hours may be used as an adjunct treatment with free water or dextrose 5% replacement.

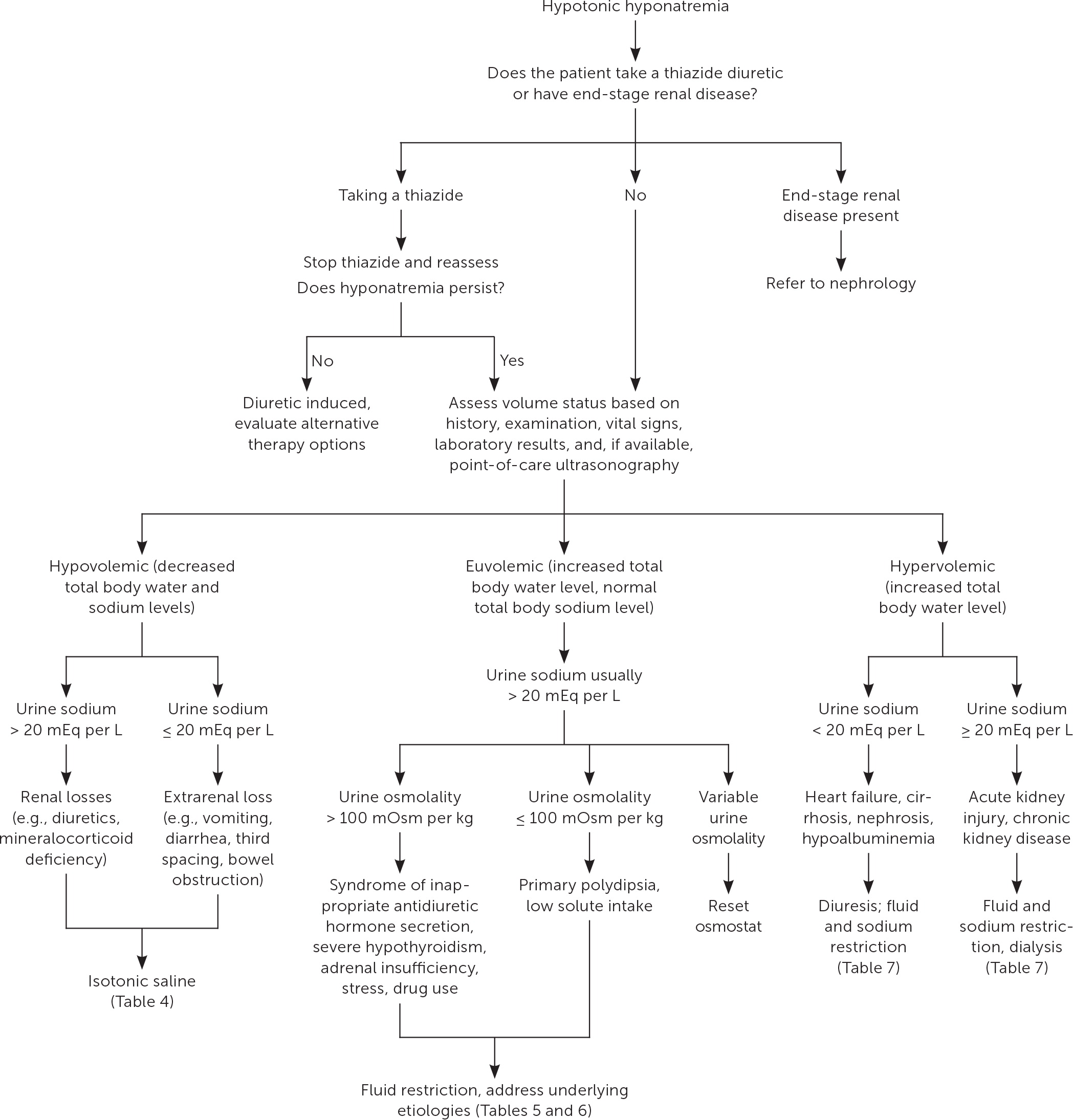

ASSESSING VOLUME STATUS

In the absence of severe hyponatremia, management of hypotonic hyponatremia (true hyponatremia) is based on whether the patient is hypovolemic, euvolemic, or hypervolemic2,10 (Figure 411). Volume status is often challenging to assess on physical examination, and algorithms are not always accurate.15 Laboratory findings can also be misleading indicators of volume status or causes of hyponatremia.16,17 For example, patients who are euvolemic due to fluid retention in the syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH) and patients who are hypovolemic due to diuretic use can both have the same findings of low serum sodium and high urine sodium.15 Low-quality evidence suggests that calculating the fractional excretion of uric acid can help distinguish high urine sodium concentration caused by SIADH vs. loop diuretics, although not thiazide diuretics.18

HYPOVOLEMIC HYPONATREMIA

| Etiology | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Diuretic use | Clinical; urinary sodium > 20 mEq per L | Stop diuretic therapy |

| Gastrointestinal loss (e.g., diarrhea, vomiting) | Clinical; urinary sodium ≤ 20 mEq per L | Intravenous fluids (normal saline) |

| Osmotic diuresis | Elevated glucose level, mannitol use | Correct glucose level; stop mannitol use |

| Salt-losing nephropathies (previously known as cerebral salt wasting) | Urinary sodium > 20 mEq per L | Isotonic or hypertonic saline; address underlying cause |

| Third spacing (e.g., bowel obstruction, burns) | Clinical; computed tomography | Intravenous fluids; relieve obstruction |

When no severe symptoms are present, treatment is volume repletion with normal saline and addressing the underlying cause, if possible.2,10 Guidelines do not specify the volume and rate of saline administration. The clinical assessment of volume needs should guide repletion. Occasionally, salt tablets may help with correction when oral therapy is appropriate, but data are lacking on outcomes and how much to prescribe.21

EUVOLEMIC HYPONATREMIA

Etiologies of euvolemic hyponatremia include primary polydipsia; decreased solute intake; cortisol deficiency; and SIADH, which can be caused by medications, pain, psychosis, and surgery 2,7,22 (Table 511). Reset osmostat, another cause of SIADH, occurs when plasma osmolality is low but ADH secretion is elevated. SIADH is considered a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, ruling out other causes of euvolemic hyponatremia is recommended.2

| Etiology | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy) use | Urine drug screening | Stop drug use; supportive care |

| Alcohol use with low solute intake (i.e., beer potomania syndrome) | Excessive alcohol consumption, low serum osmolality | Therapy to decrease alcohol use; nutritional counseling to increase protein intake |

| Exercise-associated hyponatremia (e.g., in endurance athletes or military trainees) | Clinical; excessive free water consumption | Isotonic or hypertonic saline, depending on symptoms |

| Glucocorticoid deficiency (hypocortisolism) | Low aldosterone, morning cortisol, and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels; hyperkalemia; increased plasma renin level | Steroid replacement therapy |

| Severe hypothyroidism | Elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone level, low free thyroxine level | Thyroid replacement therapy |

| Low solute intake (e.g., tea and toast diet) | Clinical; low urine osmolarity | Increase sodium intake |

| Nephrogenic SIADH (results from rare genetic conditions) | Decreased osmolality, urinary osmolality > 100 mOsm per kg, euvolemia, urinary sodium > 20 mEq per L, absence of thyroid disorders or hypocortisolism, normal renal function, no diuretic use | Fluid restriction; loop diuretics |

| Psychogenic polydipsia | History of schizophrenia with excessive water intake | Psychiatric therapy |

| Reset osmostat | Elevated antidiuretic hormone secretion; normal fractional excretion of uric acid (urate) | No therapy needed |

| SIADH | Decreased osmolality, urinary osmolality > 100 mOsm per kg, euvolemia, urinary sodium > 20 mEq per L, absence of thyroid disorders or hypocortisolism, normal kidney function, no diuretic use | Treat the underlying condition with fluid restriction, salt tablets, urea; consider vaptans |

| SIADH secondary to medication use (e.g., barbiturates, carbamazepine, diuretics, opioids, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tolbutamide, vincristine) | SIADH with use of causative agent | Stop causative medication |

| Water intoxication | Clinical; excessive water intake | Stop free water ingestion; hypertonic saline if needed for symptoms |

First-line management for nonsevere euvolemic hyponatremia includes discontinuing offending medications, addressing underlying etiologies, and restricting free water to 500 mL per 24 hours. However, adherence to that degree of water restriction can be difficult for patients, and allowing 1 L fluid restriction has also been effective.2,23,24

| Treatment | Dosage | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Empagliflozin (Jardiance) | 25 mg administered orally once per day | Limited evidence; not supported by guidelines or FDA approved for this indication |

| Salt tablets | Commonly administered as 1 g of sodium chloride three times per day; can be followed by 20 mg of furosemide | Limited evidence |

| Urea (oral) | Initiated at 15 to 60 g per day, often dissolved in a liquid drink to mask the taste | Considered a medical food instead of a medication; therefore, its safety has not been rigorously evaluated; the FDA says it is “generally recognized as safe,” but it is not FDA approved; some evidence shows that urea improves sodium concentration |

| Vaptans | Vaptans should be initiated in a hospital setting; intravenous conivaptan (Vaprisol) may be used for four days; oral tolvaptan may be used for up to 30 days, including after discharge | Should not be combined with fluid restriction because of potential for rapid sodium recovery; no evidence of long-term benefits, and use has not been assessed in severe symptomatic hyponatremia |

HYPERVOLEMIC HYPONATREMIA

Common causes of hypervolemic hyponatremia include heart failure, severe liver disease, chronic kidney disease, and nephrotic syndrome (Table 711). Initial therapy for mild to moderate hypervolemic hyponatremia with heart failure includes fluid restriction of 1 L per day, decreasing or discontinuing contributing medications, such as diuretics, and increasing dietary sodium if possible.2 Urea or vaptans may also be used.

| Etiology | Diagnosis | Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | Clinical (e.g., jugular venous distention, edema), elevated B-type natriuretic peptide level, echocardiography, urinary sodium < 20 mEq per L | Diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers |

| Kidney failure (acute or chronic) | Blood urea nitrogen to creatinine ratio, glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, urinary sodium > 20 mEq per L Serum osmoles can be normal or high due to elevated blood urea nitrogen level To correct: tonicity = measured serum osmolality − (blood urea nitrogen ÷ 2.8) | Treat kidney failure; correct the underlying disease when possible |

| Liver failure/cirrhosis | Elevated liver function test results, ascites, elevated ammonia level, biopsy, urinary sodium < 20 mEq per L | Furosemide, spironolactone, transplant |

| Nephrotic syndrome | Urinary protein, urinary sodium < 20 mEq per L | Treat underlying cause |

For patients with cirrhosis and mild hypervolemic hyponatremia, fluid restriction of 750 mL per day and loop diuretics are indicated.2 In patients with moderately severe liver failure and hypervolemic hyponatremia, decreasing or discontinuing diuretics and relying on fluid restriction alone may be appropriate to prevent further sodium loss.

Hypernatremia

Hypernatremia most commonly results from decreased water intake, often due to impaired thirst mechanisms, restricted access to water, or excess water loss (e.g., sweating, diuresis). Patients at the extremes of age, with poor functional status, or with limited cognitive capabilities are at higher risk due to their dependence on others for hydration.3,29 Hypernatremia can also occur from excessive salt ingestion, iatrogenically (i.e., when patients receive excess sodium through hypertonic saline infusions), or diabetes insipidus31,32 (Table 811,29,31–33).

| Etiology | Description | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Increased free water loss | ||

| Diabetes insipidus | May be due to central diabetes insipidus (insufficient production of antidiuretic hormone [arginine vasopressin]) or nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (decreased renal responsiveness to arginine vasopressin) Low activity causes the excretion of inappropriately dilute urine Patients may compensate by increasing fluid intake, resulting in polydipsia and polyuria; this increased intake of free water may attenuate the increase in sodium | Serum and urine electrolytes showing hypotonic urine Water deprivation testing can confirm diagnosis, and arginine vasopressin (desmopressin) stimulation test can determine central vs. nephrogenic diabetes insipidus |

| Environmental exposure | Prolonged exposure to hot, arid environments | Clinical history |

| Gastrointestinal losses | Fluid loss from vomiting or diarrhea; nausea may prevent patients from consuming enough fluid | History of nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea |

| Iatrogenic | Overdiuresis | History of diuretic use |

| Increased metabolic demands | Fever or increased physical activity | Clinical history |

| Sweating | Fluid lost through sweat, such as from environmental exposure or exercise | Clinical history |

| Decreased free water intake | ||

| Hypodipsia | Patients who are physically and cognitively capable of obtaining free water yet fail to do so; may be due to decreased thirst response, which can occur in older adults or people with psychiatric disorders such as depression | Clinical history |

| Iatrogenic | Patients who are restrained, sedated, intubated, not allowed to drink, or housed in a long-term care facility may not receive adequate amounts of water from medical personnel | Clinical history |

| Physical and cognitive limitations | Patients who are reliant on others to provide sufficient water or those who are unable to obtain safe water; may include young children, patients with disabilities, or those with poor access to water due to disaster, falls, or other adverse circumstances | Clinical history |

| Increased sodium intake | ||

| Iatrogenic | Hypertonic dialysis or administration of fluids with a supraphysiologic salt load such as hypertonic saline or sodium bicarbonate | History of dialysis or medication administration |

| Salt toxicity | Rapid ingestion of excessive amounts of salt can acutely increase the serum sodium concentration A rare condition with high mortality | History of excessive salt ingestion |

SYMPTOMS

Symptoms of hypernatremia in adults are typically nonspecific and include fatigue, lethargy, and weakness.32,34 Symptoms in children may be similarly nonspecific, including weight loss, poor feeding, irritability, restlessness, lethargy, decreased urine output, constipation, and vomiting.29 In children and adults with severe hypernatremia, symptoms may progress to seizures, coma, and death.28,29,32,34

DIAGNOSIS

The cause of hypernatremia is often apparent from the patient's history. Physical examination may find evidence of dehydration, including orthostatic hypotension.

Further laboratory evaluation is occasionally required to identify uncommon causes, such as diabetes insipidus. Hypernatremia should be considered when patients report large urine volumes and extreme thirst.

Urinalysis showing dilute urine in the presence of dehydration suggests diabetes insipidus. A diagnosis of diabetes insipidus is complex.35 The first step is to perform a water deprivation test, in which the patient does not drink liquid for an extended time. Continued polyuria with dilute urine is consistent with diabetes insipidus.35

MANAGEMENT

Hypernatremia is associated with increased mortality rates in hospitalized patients, especially when not quickly identified and corrected.27,34,36 First-line treatment is addressing the underlying cause and correcting the fluid deficit. The formula and calculator for computing the free water deficit are listed in Table 3.11

The calculated deficit volume can be administered over 24 hours. Oral or enteral free water should be used whenever possible. If intravenous fluids are required, hypotonic fluids such as dextrose 5% in water should be used. Isotonic saline should be avoided because it can worsen hypernatremia.33

Rapid correction of hypernatremia in dehydrated infants has been associated with poor neurologic outcomes, including seizures.29 The maximum acceptable rate of sodium correction in infants is unclear; however, rates of less than 0.5 mEq per L per hour (less than 12 mEq per L in 24 hours) are associated with the lowest risk.29,37

In adults, rapid correction does not appear to cause poor neurologic outcomes, and failure to correct hypernatremia within 72 hours has been associated with worsening mortality in hospitalized patients.27,30 Although a correction of less than 10 mEq per L per 24 hours has been recommended based on expert opinion, more recent evidence suggests that hypernatremia in adults can be corrected at a rate of 12 mEq per L over 24 hours. However, if 12 mEq per L per 24 hours is exceeded, therapeutically increasing the serum sodium again should be avoided.30,37

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Braun, et al.11

Data Sources: We were provided a search from Essential Evidence Plus using the key term hyponatremia. A search was completed using the key terms hyponatremia, diagnosis, euvolemic hyponatremia, and treatment. Also searched were the Cochrane database, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Google Scholar, and PubMed from January 1, 2010, to October 2022. The searches were limited to English-language studies. Secondary references from the key articles identified by the searches were also used. Our review did not incorporate race or gender as patient categories. Search dates: August to October 2022, and September 2023.