This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(5):487-493

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Parasites are a source of significant illness worldwide. In the United States, giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, cyclosporiasis, and trichinellosis are nationally notifiable conditions. Pinworm, the most common intestinal parasite in children, is not a locally notifiable infection. Intestinal parasites have a wide range of acute and chronic symptoms but should be suspected in those who present with diarrhea lasting more than seven days. Infections most often occur through a fecal-oral route. Symptoms tend to be worse for children, older adults, or immunocompromised individuals. To diagnose Giardia infection, stool microscopy with direct fluorescent antibody testing is recommended; metronidazole, nitazoxanide, or tinidazole is used for treatment. Microscopy with immunofluorescence is sensitive and specific for diagnosing Cryptosporidium infection. This infection is often self-resolving, but treatment with nitazoxanide is effective for symptoms lasting more than two weeks. Microscopy or polymerase chain reaction assays are recommended to diagnose Cyclospora infections, and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim may be used to treat patients with persistent diarrhea. Trichinella infection is diagnosed by serum antibody testing, and severe symptoms are treated with albendazole in patients older than one year. Pinworm infections are diagnosed visually or by a tape test or paddle test; albendazole and pyrantel pamoate are both effective treatments.

Intestinal parasites found in the United States include one-celled protozoa and soil-transmitted helminths. Examples of nationally notifiable one-celled protozoa infections include giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, and cyclosporiasis.1,2 Soil-transmitted helminths are the most common intestinal parasites worldwide, causing an estimated 2.6 billion infections per year.3 The most common soil-transmitted helminth in the United States is Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm).4 Trichinella (roundworm) is another soil-transmitted helminth and is nationally notifiable in the United States.1,2 [corrected] Parasites generally spread through a fecal-oral route. Good hygiene, handwashing, and proper handling of food and water are key to preventing intestinal parasitic infections. Additional specific guidance for prevention is listed in Table 1.5–8

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| In immunocompetent patients without a history of travel to areas with endemic parasites, ova and parasite examination should not be ordered if diarrhea has lasted fewer than seven days.9,10 | C | Choosing Wisely and the 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America clinical practice guideline |

| Microscopy with direct fluorescent antibody testing is the preferred test for Giardia.18,20 | C | Expert opinion and comparative diagnostic studies |

| A single dose of tinidazole is the most effective treatment for people older than three years with Giardia infection (greater than 90% cure rate).12,13 | A | Systematic review and network meta-analysis |

| Cryptosporidium infection with diarrhea persisting beyond two weeks should be treated with nitazoxanide (Alinia).14 | A | Prospective randomized controlled trial |

| Parasite | Prevention strategies |

|---|---|

| Giardiasis5 | Boil water for at least 10 minutes |

| Apply iodine water treatments for eight or more hours | |

| Use a water microfilter with a 1-micron pore | |

| Cryptosporidiosis5 | Individuals with infection should avoid public pools for two weeks postdiarrhea |

| Freeze water | |

| Boil water for at least 10 minutes | |

| Use a water microfilter with a 1-micron pore | |

| Use high concentrations of ammonia or formalin to purify the water | |

| Cyclosporiasis6 | Drink boiled or bottled water in endemic areas |

| Wash fruits and vegetables thoroughly under running water | |

| Do not eat raw produce from endemic areas | |

| Use ultraviolet disinfection | |

| Trichinellosis7 | Cook meat to an internal temperature of 145°F to 171°F (63°C to 77°C) |

| Freeze meat at 5°F (−15°C) for three weeks, which will typically kill larvae | |

| Irradiate sealed packed meat | |

| Pinworm8 | Wash bedding and clothing |

| Clip fingernails | |

| Take a shower instead of a bath | |

Intestinal parasites should be suspected in patients who have diarrhea lasting seven days or more. Obtaining a detailed history is important for diagnosis. In patients without immunodeficiency or history of living in or traveling to areas where intestinal parasites are endemic, comprehensive stool ova and parasite microscopic examination should not be ordered if diarrhea has not lasted seven days.9

For presumed infectious diarrhea of seven days or longer, evaluation should start with molecular or antigen testing; comprehensive stool ova and parasite testing is indicated if negative.10 Most patients with healthy immune systems will clear intestinal parasites on their own without treatment, but testing can be considered for persistent symptoms or for identification of the pathogen when necessary for public health reasons.

| Disease | Medication | Dosing | Cure rate | Common adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Giardiasis | Metronidazole (Flagyl)*† | Adults 500 mg twice daily for five to seven days or 250 mg three times daily for five to seven days Infants, children, adolescents 5 to 10 mg per kg three times daily for five to seven days; maximum of 250 mg per dose |

80% when treating children Diarrhea resolution11 |

Central nervous system effects, disulfiram-like reaction when mixed with alcohol, gastrointestinal discomfort, headache, metallic taste, nausea, pruritus |

| Nitazoxanide (Alinia)‡ | Individuals older than 11 years 500 mg twice daily for three days Children four to 11 years of age 200 mg twice daily for three days Children one to three years of age 100 mg twice daily for three days |

85% when treating children Diarrhea resolution11 |

Abdominal pain, bright yellow urine, headache, nausea | |

| Tinidazole†§ | Adults One 2-g dose Children older than three years 50 mg per kg in one dose, maximum of 2 g per dose |

> 90% for children and adults Parasitic cure12,13 |

Central nervous system effects, disulfiram-like reaction when mixed with alcohol, gastrointestinal discomfort, headache, metallic taste, nausea, pruritus | |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Nitazoxanide‡ | Patients older than 11 years 500 mg twice daily for three days Children four to 11 years of age 200 mg twice daily for three days Children one to three years of age 100 mg twice daily for three days |

80%14 | Abdominal pain, bright yellow urine, headache, nausea |

| Cyclosporiasis | Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim*† | Adults 800 mg/160 mg twice daily for seven to 10 days Children Limited data available |

96%15 | Anorexia, blood dyscrasias, Clostridioides difficile infection, diarrhea, hyperkalemia, hypersensitivity reactions, hypoglycemia, hyponatremia, kernicterus, liver injury, nausea, rash, vomiting |

| Trichinellosis | Albendazole*|| | Patients older than six years 400 mg twice daily for eight to 14 days Children one to six years of age 5 to 10 mg per kg per day, divided twice daily for 10 to 15 days |

Limited human data available | Abdominal pain, elevated liver function test, headache, increased intracranial pressure, nausea, reversible alopecia, vomiting |

| Pinworm | Albendazole* | Patients older than two years and adolescents 400 mg once; repeat in two to three weeks later Children two years and younger 200 mg once; repeat dose in three weeks |

> 90%16 | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, headache, elevated findings on liver function tests, increased intracranial pressure, reversible alopecia |

| Mebendazole¶ | Adults 100 mg once; repeat in two weeks Children Limited data available but two years and older, 100 mg once; repeat in two weeks |

>90%16 | Abdominal pain, angioedema, anorexia, diarrhea, dizziness, fatigue, fever, flatulence, headache, hepatitis, nausea, vomiting, weakness | |

| Pyrantel pamoate** | Patients older than two years 11 mg per kg once, followed by repeat dose two weeks later (maximum of 1 g per dose) |

> 90%16 | Nausea, vomiting, anorexia, abdominal cramps, diarrhea |

Giardiasis

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Giardiasis is caused by the protozoon Giardia duodenalis (also called Giardia lamblia and Giardia intestinalis). In the United States, 15,000 to 20,000 cases of Giardia infection are reported annually, but underreporting is suspected. In 2019, the reported incidence of Giardia infection was 5.59 cases per 100,000 people.17 Giardia has been found throughout the United States and generally infects people in the summer through fall.17 It is most commonly reported in children younger than five years.17 The role of animals and pathogenesis is poorly understood.

The Giardia cyst is highly infectious and can withstand harsh conditions, including chlorinated water. Individuals at highest risk of Giardia infection include those in child-care settings or in close contact with a positive individual or domestic or wild mammals, travelers in areas with poor sanitation, backpackers or swimmers drinking contaminated water, people who use water from a shallow well (e.g., less than 7.5 m [25 ft]), and those with weakened immune systems or who engage in oral-anal intercourse.17

DIAGNOSIS

Symptoms of Giardia infection usually occur one to two weeks after ingestion of cysts.18 Presentation ranges from no symptoms to, rarely, severe diarrhea that requires hospitalization. Diarrhea is typically loose, foul smelling, fatty, and nonbloody.18 Other common symptoms include malaise, flatulence, abdominal cramping, bloating, nausea, anorexia, weight loss, fever, constipation, and urticaria.

Chronic giardiasis can occur after an acute phase or present in isolation in up to one-half of individuals infected.19 Abnormal stools, weight loss of up to 11.34 kg (25 lb), fatigue, malabsorption, and depression can wax and wane over months; these symptoms may be mistaken for irritable bowel syndrome.19 Without proper treatment, this can lead to vitamin D deficiencies, stunted growth, or lactase deficiency. Rarely, Giardia can spread to the biliary and pancreatic ducts, leading to gallbladder, liver, and pancreatic complications.

Testing for Giardia infection should be considered when diarrhea lasts longer than seven days. Antigen detection assays, polymerase chain reaction assays, and stool microscopy are options, although stool microscopy with direct fluorescent antibody testing is preferred for Giardia.18 Antibody and antigen methods have a greater sensitivity (91% to 100%) and specificity (89% to 100%), produce quicker results, and are more cost-effective than conventional microscopy for ova and parasites (comprehensive stool ova and parasite examination).20 Giardia is seen about 50% of the time with one comprehensive stool ova and parasite microscopy sample and up to 90% of the time in three or more samples.20 Laboratory tests for serum or fecal leukocytosis or eosinophilia are not helpful.

TREATMENT

In asymptomatic, immunocompetent patients with Giardia infection, treatment should be based on shared decision-making.21 The benefit of treatment likely outweighs the risk of no treatment in patients who are asymptomatic but immunocompromised or living with someone who is immunocompromised, in group settings, and in those who handle food.21

Metronidazole (Flagyl), nitazoxanide (Alinia), or tinidazole is often used to treat Giardia infection. Less commonly used options include albendazole, furazolidone, mebendazole (available as brand Emverm), paromomycin, and quinacrine. A single dose of tinidazole is highly effective, with cure rates of more than 90% in individuals older than three years.12 Supportive care with fluids and electrolyte replacement is recommended in patients with Giardia infection, based on hydration status.

Symptoms are self-limited and generally last two to six weeks, although immunocompromised individuals may have longer duration symptoms18; the symptoms usually resolve five to seven days after starting treatment. For patients with chronic giardiasis, symptoms may take several months to resolve. Testing is performed after treatment only if symptoms persist. A test of cure is not required. Recurrent symptoms may warrant repeat stool testing (stool antigen or polymerase chain reaction), and physicians should evaluate for a potential reinfection source. Antigen detection assays are of limited use after treatment because antigens can still be detected in stool after eradication of the parasite.

Options for retreatment are the same agent, a different agent, or a combination of agents, depending on patient history. Individuals should avoid dairy for one month after treatment of Giardia infection because of the possibility of lactose intolerance resulting from the infection, which occurs in 20% to 40% of people.22

Cryptosporidiosis

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium hominis are among the most common intestinal parasites in humans, but they are rarely reported. Cryptosporidium infections generally occur from early summer to late fall, with outbreaks related to drinking water contamination, animal contact, travel, and use of swimming pools and recreational water facilities. Oocysts are hardy and can remain viable for many months. Most cases of Cryptosporidium infections occur in children younger than five years, men who have sex with men, and dairy farmers.23

DIAGNOSIS

Patients can be asymptomatic or have symptoms ranging from mild watery diarrhea to severe enteritis with possible biliary tract and pulmonary involvement.24 The incubation period is seven to 10 days. Symptoms often resolve without therapy within two weeks in immunocompetent individuals.24 In those who are immunocompromised, long-term sequelae include abdominal pain, diarrhea, joint pain, weight loss, and fatigue.24

Microscopy with immunofluorescence has the greatest sensitivity and specificity (99.8% to 100% for both), followed by enzyme immunoassays and polymerase chain reaction.25 Routine comprehensive ova and parasite stool examinations do not detect Cryptosporidium oocysts. Therefore, suspicion of oocysts should be noted on laboratory orders so that modified staining techniques will be used. Serum alkaline phosphatase may be elevated in patients with biliary tract involvement. Ultrasonography and computed tomography may show an enlarged gallbladder with a thickened wall and dilated biliary ducts.

TREATMENT

Hydration and supportive therapies are the mainstay of treatment. Antidiarrheal agents can be used as needed. In immunocompetent individuals, spontaneous recovery typically occurs within a few days to one week, and parasitic cure happens within a few weeks to months without the need for any specific therapy. If symptoms persist beyond two weeks, antibiotics may be needed. Nitazoxanide is the preferred treatment for cryptosporidiosis and is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication.14 If symptoms continue after treatment, the patient should be retested for persistent infection or reinfection.

Cyclosporiasis

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Cyclospora cayetanensis is a foodborne, waterborne, and soil-transmitted parasite with a broad geographic distribution spanning Latin America, Egypt, sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Southeast Asia.6 Cases reported in the United States often occur in international travelers or those who have ingested fresh produce imported from endemic regions.26,27

Between 2011 and 2015, there were 2,207 cases of cyclosporiasis reported in the United States—including 10 outbreaks with 1,988 confirmed cases—largely during the spring and summer.28 The annual incidence in 2013 was 0.29 per 100,000 people.28 In 2020, there were 1,241 cases of cyclosporiasis reported in 24 states, including one large outbreak due to contaminated bagged salad mix.29 No deaths occurred in this outbreak, and 5% of infected patients were hospitalized.29

Oocysts are not infectious when passed in the stool; therefore, direct person-to-person transmission is unlikely. Sporulation occurs one to two weeks after the infected stool is out of the host and in temperatures between 72°F and 90°F (22°C and 32°C). Sporozoites contaminate fresh produce or water, which become vehicles for transmission. The infective dose is unknown but likely very low (10 to 100 oocysts).27 Humans are the only known host for the organism.

DIAGNOSIS

After ingestion, the average incubation period is about seven days.6 Cyclospora infections can be asymptomatic or cause symptoms, such as waxing and waning anorexia, abdominal cramping, fatigue, flatulence, low-grade fever, nausea, watery or bloody diarrhea, and weight loss, that last a few days to months or longer.6 Symptoms are typically more severe in people who are immunosuppressed, younger, or older.6 Protracted diarrhea can lead to dehydration, especially if cyclosporiasis is complicated by additional infections.6 Rare extraintestinal manifestations of cyclosporiasis, typically in patients who are immunocompromised, include biliary disease (acalculous cholecystitis), Guillain-Barré syndrome, reactive arthritis, inflammatory oligoarthritis, ocular inflammation (e.g., conjunctivitis, iritis, episcleritis), and urethritis.30

Cyclosporiasis should be considered in patients with prolonged diarrhea or recent travel to an endemic area. Stool microscopy can detect oocysts. However, because low numbers of oocytes shed in the stool, multiple fecal specimens should be collected at two- to three-day intervals. Stool testing for ova and parasites usually does not include cyclosporiasis; therefore, special testing or polymerase chain reaction assays (95% sensitive and specific) should be requested.30,31 Serologic testing is not available for cyclosporiasis.

TREATMENT

For immunocompetent adults with cyclosporiasis, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim is the only treatment. No effective alternative has been identified for patients with a sulfa allergy or intolerance. Other antibiotics, such as nitazoxanide, have been cited as potential treatments, but they have higher failure rates.9 Sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim is the considered treatment for children, but it is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this specific indicaton.32 Repeat stool testing is not recommended if diarrhea has resolved.9

Trichinellosis

EPIDEMIOLOGY

At least seven Trichinella species cause trichinellosis. This infection most often affects adults who have ingested raw or undercooked pork, wild boar, bear, deer, or ground beef. Surveillance data suggest that the annual incidence has decreased over time and that the condition is rare.33

DIAGNOSIS

Trichinellosis presents with nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms and diarrhea. Severe symptoms such as fever, eosinophilia, myositis, and circumorbital edema occur when ingested larvae develop into worms that travel to lymphatic, circulatory, and musculoskeletal systems. Some episodes of trichinellosis resolve spontaneously, but the syndrome can also be fatal if the central nervous system is affected.

Diagnosis of trichinellosis is confirmed by serum antibody testing, but tests often do not accurately detect the disease in the first three weeks of illness. Immunologic testing is complex and requires two serum specimens drawn several weeks apart. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends consulting with its Parasitic Diseases Hotline for assistance when the disease is suspected (https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/contact.html). Trichinella larvae can be identified via biopsy of muscle tissue34; the larvae can also be seen on brain imaging if the central nervous system is involved. Elevated serum creatine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, and hypergammaglobulinemia may be present.

TREATMENT

With clinical suspicion and mild disease, antiparasitic treatment is not needed. Albendazole is the treatment of choice in patients older than one year who have systemic involvement. Patients with severe symptoms may benefit from 10 to 15 days of systemic steroids (e.g., prednisone, 30 to 60 mg per day, until fever and symptoms improve).

Enterobius vermicularis (Pinworm)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Pinworm is the most common intestinal parasite, infecting an estimated 40 million people in the United States.8 Humans are the only natural host, and transmission occurs as a result of direct contact with contaminated skin or items, most often in crowded environments and especially within families. Children, their caretakers, and people who care for patients in institutions are at high risk of infection. Younger age, male sex, and living in rural areas are commonly associated with pinworm infections.35 The Enterobius eggs are ingested, then develop into adult worms that live in the human intestine. Female worms emerge at night to deposit eggs in the anal region.

DIAGNOSIS

Most people with an Enterobius infection do not have symptoms, but pruritus may occur. Localized bacterial infections can develop because of inflammation and pruritus around the anus and in the genitourinary regions. Rarely, appendicitis can develop because of chronic pinworm infection.

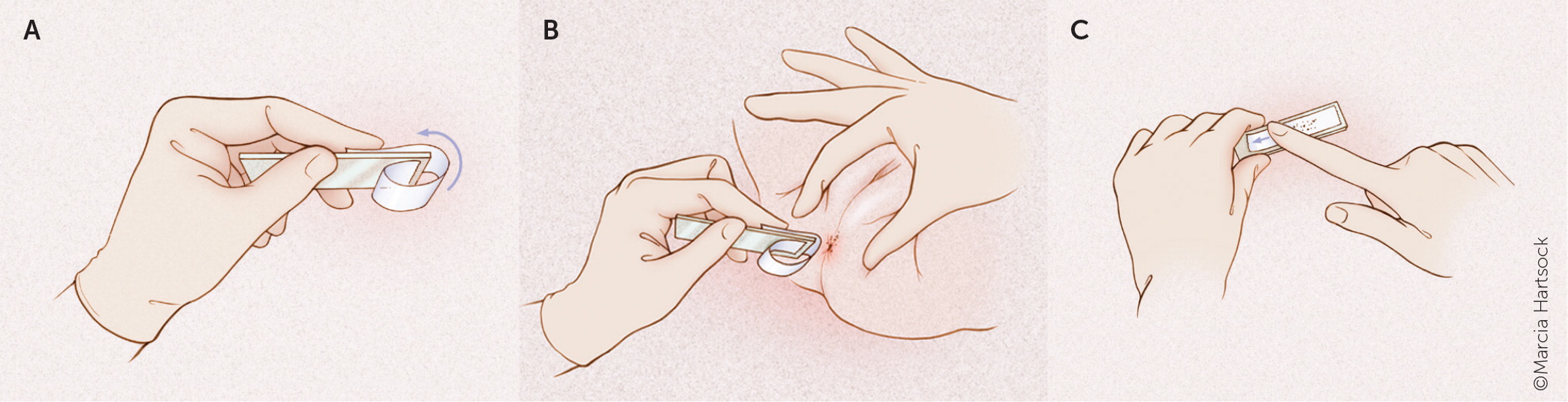

Direct visualization of pin-shaped, white, 8- to 13-mm worms in the perianal region is diagnostic.8 The tape test (Figure 136) or pinworm paddle test is performed by pressing an adhesive against the perianal region and then placing it on to a glass slide.8 Microscopic examination verifies the presence of eggs or worms. The yield is best at night or first thing in the morning.8 Samples from under fingernails can be examined under microscopy to verify pinworm eggs.8 Stool testing is not recommended because the worms are not excreted directly in the stool.8

TREATMENT

Albendazole or mebendazole is the recommended treatment, but pyrantel pamoate is also effective and available over the counter.8 Because reinfection is common, treating all members of the patient's household should be considered if symptoms persist.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Kucik, et al.36

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term intestinal parasites. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports, the Cochrane database, DynaMed, and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Search dates: January 1 and October 4, 2023.

Editor's Note: Dr. Pyzocha is a contributing editor for AFP.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.