This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(5):454-463

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Syncope is an abrupt, transient, and complete loss of consciousness associated with an inability to maintain postural tone; recovery is rapid and spontaneous. The condition is common, resulting in about 1.7 million emergency department visits in 2019. The immediate cause of syncope is cerebral hypoperfusion, which may occur due to systemic vasodilation, decreased cardiac output, or both. The primary classifications of syncope are cardiac, reflex (neurogenic), and orthostatic. Evaluation focuses on history, physical examination (including orthostatic blood pressure measurements), and electrocardiographic results. If the findings are inconclusive and indicate possible adverse outcomes, additional testing may be considered. However, testing has limited utility, except in patients with cardiac syncope. Prolonged electrocardiographic monitoring, stress testing, and echocardiography may be beneficial in patients at higher risk of adverse outcomes from cardiac syncope. Neuroimaging should be ordered only when findings suggest a neurologic event or a head injury is suspected. Laboratory tests may be ordered based on history and physical examination findings (e.g., hemoglobin measurement if gastrointestinal bleeding is suspected). Patients are designated as having lower or higher risk of adverse outcomes according to history, physical examination, and electrocardiographic results, which can inform decisions regarding hospital admission. Risk stratification tools, such as the Canadian Syncope Risk Score, may be beneficial in this decision; some tools include cardiac biomarkers as a component. The prognosis of patients with reflex and orthostatic syncope is good; cardiac syncope is more likely to be associated with adverse outcomes.

Syncope is an abrupt, transient, and complete loss of consciousness associated with an inability to maintain postural tone; recovery is rapid and spontaneous. The definition of syncope does not include loss of consciousness caused by other conditions, such as seizures or head trauma. Presyncope refers to the symptoms that occur before an episode of syncope, such as graying out or tunnel vision; these symptoms may progress to syncope or resolve without total loss of consciousness.1

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Avoid computed tomography of the head in asymptomatic adult patients in the emergency department with syncope, insignificant trauma, and a normal neurologic evaluation. | American College of Emergency Physicians |

| In the evaluation of simple syncope and a normal neurologic examination, do not obtain brain imaging studies (i.e., computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging). | American College of Physicians |

| Do not perform imaging of the carotid arteries for simple syncope without other neurologic symptoms. | American Academy of Neurology |

| Do not routinely order electroencephalography as part of the initial syncope workup. | American Epilepsy Society |

Syncope is a common symptom that results in substantial use of health care resources and expenses. The lifetime incidence of syncope is reported to range between 19% and 41%, and it is more prevalent with advanced age and female sex.1,2 Syncope was the cause of 1.7 million U.S. emergency department visits in 2019, or 1.1% of all such visits.3 As of 2014, 25% of individuals evaluated for syncope in emergency departments were admitted, and 10% were given observation status.4

Pathophysiology

The immediate cause of loss of consciousness in a syncopal episode is cerebral hypoperfusion. The two primary mechanisms of this hypoperfusion are systemic vasodilation and decreased cardiac output. Either, or both, can lead to syncope. Systemic vasodilation may be due to autonomic nervous system dysfunction, excessive response to various stimuli (e.g., emotion, position, other triggers), and medication. Decreased cardiac output may be caused by intrinsic heart disease (e.g., coronary artery disease, heart failure, valvular disease), or it may be secondary to hypovolemia, orthostatic hypotension, or neurally mediated bradycardia (as in vasovagal syncope).

Differential Diagnosis

Syncope must be distinguished from other nontraumatic conditions that lead to transient loss of consciousness. These include seizures, psychogenic causes, and rare conditions such as vertebrobasilar transient ischemic attacks, subclavian steal syndrome, cataplexy, hypoglycemia, and drop attacks.5,6 Jerking movements are not unique to seizures and may also occur in syncope. Features of these movements that suggest syncope as the etiology include an onset following loss of consciousness, asymmetry, loss of muscle tone, and being fewer in number, such as fewer than 10 movements, per episode. Loss of consciousness for less than 30 seconds suggests syncope; a duration longer than 60 seconds suggests seizures. Confusion after the event suggests that seizures are the cause.5,7

Syncope is categorized as cardiac, reflex (neurogenic), or orthostatic (Table 1).1,5,8–11 More than one of these mechanisms may be involved in any given episode. Cardiac syncope is caused by cerebral hypoperfusion due to decreased cardiac output. It is the type of syncope most often associated with sudden cardiac death and increased mortality.5

| Type of syncope | Scenario | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|

| Reflex (neurogenic; 35% to 48% of cases*) | ||

| Carotid sinus hypersensitivity | Associated with pressure on the neck, such as shaving, wearing a tight collar, and turning the head; consider in patients with unexplained falls | Stimulation of the carotid sinus can cause ventricular pause or a drop in systolic blood pressure, which is reproducible with carotid sinus massage |

| Situational | Occurs during or after defecation, urination, or coughing, or after eating or exercise | Absence of heart disease; patient has likely had previous similar experiences |

| Vasovagal | Inappropriate (nonphysiologic) vasodilation and bradycardia; caused by fear, pain, noxious stimuli, heat, or stress | May have prodromal features, such as nausea, warmth, or diaphoresis |

| Cardiac (5% to 21% of cases*) | ||

| Arrhythmia | Palpitations may precede syncope; sometimes lacks prodrome; may be unprompted | Abnormal electrocardiographic findings (e.g., bradyarrhythmias, tachyarrhythmias, pacemaker dysfunction); family history of sudden death; personal history of heart disease; abrupt onset of palpitations or symptoms while supine or prone |

| Structural | Cardiac tamponade | Hypotension, tachycardia, increased jugular venous pressure, pulsus paradoxus |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Family history of sudden cardiac death, systolic murmur that intensifies during Valsalva maneuver | |

| Infiltrative diseases (e.g., amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis) | Arrhythmias, heart block, heart failure | |

| Valvular | Aortic, mitral, or pulmonic stenosis | Symptoms depend on severity; may cause heart failure, exertional angina; murmur may be heard on examination |

| Vascular (may be associated with electrocardiographic changes) | Acute myocardial infarction or ischemia | Chest pain, diaphoresis, shortness of breath, onset with exertion |

| Aortic dissection | Hypotension or shock, severe sharp chest pain that possibly radiates to the back | |

| Pulmonary embolism | Shortness of breath; fatigue; may be asymptomatic | |

| Orthostatic (4% to 24% of cases*) | ||

| Autonomic failure | Neurogenic-mediated orthostasis; failure of autonomic nervous system to compensate for positional changes | May be seen in patients with Parkinson disease, Lewy body dementia, multiple sclerosis, diabetes mellitus, connective tissue disorders, advanced age, or spinal cord injury |

| Drug-induced | Numerous medications may cause vasodilation or decreased cardiac output | Recent initiation or increased dose of medications (consider anticholinergics, diuretics, antihypertensives, dopaminergics, opiates, antipsychotics, sedatives, and tricyclic antidepressants) |

| Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome | Common in young adults; more common in females | Severe orthostasis with marked tachycardia |

| Volume depletion | Caused by poor oral intake, gastrointestinal losses, acute blood loss, and diuretics | History of blood or fluid loss; low blood pressure; elevated heart rate |

Reflex syncope is the most common type of syncope in all age groups. It may result from decreased cardiac output, systemic vasodilation, or both. Typically, a provoking factor, such as fear, pain, or emotional distress, is the source of the syncopal episode.

Orthostatic syncope occurs with positional changes, such as movement from a supine to standing position, when return of blood to the heart is temporarily diminished. This can be exacerbated by dehydration, blood loss, or medication use. In patients with autonomic dysfunction, failure of compensatory vasoconstriction also decreases cerebral perfusion.

Initial Evaluation

The evaluation of a syncopal event focuses on whether the underlying cause is likely to lead to an adverse outcome. The history, physical examination (including orthostatic measurements), and electrocardiographic (ECG) results are the primary tools to determine the etiology of the syncopal event.1,5 In one prospective study of patients presenting with syncope, the etiology in 64% of patients was diagnosed with certainty (24%) or high likelihood (40%) based only on history, physical examination, and ECG results.10 Table 2 discusses findings from the history and physical examination for syncope and their relevance.1,11–15

| History findings | Significance |

|---|---|

| Description of episode | |

| After exercise or with triggers such as cough, micturition, and defecation | May indicate reflex syncope |

| During exertion or while supine; associated with chest pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, or lack of prodrome | May indicate cardiac etiology |

| During positional changes or prolonged standing | May indicate orthostatic hypotension |

| With a prodrome of anxiety, emotional distress, fear, or pain; or a feeling of warmth | May indicate reflex syncope |

| With nausea afterward | May indicate reflex syncope |

| Medical history | |

| Current medical conditions, especially cardiac | Presence of ischemic or structural heart disease or history of arrhythmia increases likelihood of cardiac syncope |

| Family history | May suggest Brugada syndrome, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or rare conditions |

| How long patient has been having syncope | More than 4 years of syncopal episodes may indicate low risk of cardiac etiology |

| Medications | May cause or exacerbate syncope |

| Physical examination findings | |

| Arrhythmias | Tachycardia, bradycardia, and irregular rhythm may indicate cardiac syncope |

| Cranial nerve, motor, or speech deficits | Neurologic conditions rarely cause syncope, but they can occur due to head trauma following a syncopal episode |

| Murmurs | May suggest valvular disease |

| Orthostatic blood pressure | A drop in systolic blood pressure of ≥ 20 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 10 mm Hg is diagnostic for orthostatic hypotension |

| Vital signs | Systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg or > 180 mm Hg indicates higher risk Patients with reflex syncope may have higher baseline heart rate but less variation in heart rate with maneuvers (e.g., orthostatic) |

Information from the history and physical examination can help classify the patient as being at lower or higher risk of adverse outcomes. Corroborating information from someone who observed the episode is also beneficial. Important history information includes symptoms and activities before the syncopal episode, previous similar episodes, history of heart disease, recent illness, and the patient's current medications. The cardiac examination may identify an arrhythmia or murmur, and the neurologic examination may find a focal deficit, mental status change, or postictal state. Findings that indicate higher risk include associated chest pain or shortness of breath, occurrence with exertion or while supine, sudden onset of palpitations or lack of prodrome, family history of sudden cardiac death, personal history of cardiac disease, systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, gastrointestinal bleeding, persistent bradycardia, and previously undiagnosed murmur (Table 3).1,5,11–13

| Lower risk | Higher risk |

|---|---|

| Episode history | |

| After prolonged standing During or after a meal Caused by head rotation or pressure on carotid sinus Caused by positional change from supine or sitting to standing With a prodrome typical for reflex syncope With a trigger such as cough, defecation, or micturition In a younger patient | Associated with chest pain, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, headache Associated with sudden-onset palpitations Family history of sudden cardiac death at young age Lack of prodrome In a male patient Occurs during exertion Occurs while sitting or supine In an older patient |

| Medical history | |

| Absence of known heart disease History of recurrent episodes with similar low-risk features, particularly in a patient younger than 40 years | History of heart disease |

| Physical examination | |

| Normal physical examination findings | Persistent bradycardia < 40 beats per minute in the absence of physical training Suggestion of gastrointestinal bleeding Previously undiagnosed systolic murmur Unexplained systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg |

Orthostatic blood pressure and heart rate should be measured after the patient has been supine for five minutes. The patient stands, and the blood pressure and pulse are checked within one minute and again at three minutes. There is no consensus regarding additional intervals at which to check blood pressure and heart rate. A drop in systolic blood pressure of 20 mm Hg or more or a drop in diastolic blood pressure of 10 mm Hg or more upon standing is diagnostic of orthostatic hypotension. Increased heart rate is not necessary for diagnosis because this may not occur in patients with autonomic dysfunction.5 Patients with early-onset orthostatic hypotension, which occurs within 15 to 60 seconds of standing, may be at higher risk of adverse outcomes.16

ECG findings may suggest a cardiogenic cause of syncope and the need for further workup. Bradycardia, sinus pauses, high-grade heart blocks, and ventricular and supraventricular tachyarrhythmias may be identified. Certain congenital and acquired conditions that can cause syncope have recognizable ECG abnormalities (Table 4).1,5,17

| ECG findings | Significance |

|---|---|

| Changes consistent with acute ischemia Mobitz type II or third-degree atrioventricular block Persistent bradycardia Sinus pauses Ventricular or supraventricular tachyarrhythmias | Suggests high risk of adverse events, such as cardiac arrest or death |

| Complete left bundle branch block First-degree atrioventricular block Multiple premature ventricular contractions Nonsinus rhythm Other abnormalities consistent with acute or chronic ischemia Short PR interval | Increased risk of adverse events within 30 days |

| Short PR interval and delta wave | Consider Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome |

| Elevated ST segment in V1 and/or V2 with inverted T waves in these leads | Consider Brugada syndrome |

| Prolonged QT interval | QTc longer than 470 ms for men or 480 ms for women indicates long QT syndrome; can be congenital or acquired (e.g., from medications, electrolyte imbalance) |

Further Evaluation

If the history, physical examination, and ECG findings do not clearly identify the patient's risk level for adverse outcomes, further evaluation may be indicated. Although various additional tests are commonly ordered, many are performed without evidence of benefit in the evaluation of syncope (Table 5).1,5,6,12,18–23

| Test | Indication | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Carotid sinus massage | For patients older than 40 years with syncope of unknown etiology compatible with a reflex mechanism | Carotid sinus syndrome confirmed if the test causes bradycardia or hypotension that reproduces symptoms |

| Carotid ultrasonography | Neurologic findings; otherwise, carotid imaging should not be performed | Loss of consciousness not usually a symptom of transient ischemic attack associated with carotid stenosis; focal neurologic signs and symptoms would be expected with transient ischemic attack |

| Chest CT angiography | For patients with findings suggestive of pulmonary embolism | Per systematic review, the prevalence of pulmonary embolism in patients with syncope is 0.8%; not certain whether pulmonary embolism caused the syncope |

| Echocardiography | For patients with suspected structural heart disease based on initial assessment (can identify aortic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, pericardial tamponade, aortic dissection, acute right ventricular strain as seen in pulmonary embolism, and other structural conditions) | Individuals at least 60 years of age with abnormal ECG results or elevated B-type natriuretic peptide levels may benefit from transthoracic echocardiography, which the American College of Radiology recommends if clinical suspicion of cardiac etiology based on history, physical examination, or ECG results |

| Electroencephalography | Suspected seizure | Should not be ordered as part of the basic workup of syncope but appropriate if seizure is suspected |

| Electrophysiologic study | Asymptomatic sinus bradycardia (< 50 beats per minute), bifascicular bundle branch block, and tachycardia; otherwise has only limited usefulness in the workup of syncope | Should not be obtained in patients with syncope who have normal ECG results and normal heart structure unless arrhythmic etiology is otherwise suspected |

| Head CT | Only if intracranial disease is highly suspected as contributing to the syncope or there is suspicion of head trauma due to syncope | CT and magnetic resonance imaging of the head have otherwise not been shown to be of benefit in evaluation of syncope |

| Laboratory testing | Based on clinical findings | Hemoglobin if gastrointestinal bleeding is suspected Human chorionic gonadotropin in women of childbearing age d-dimer assay if pulmonary embolism is suspected B-type natriuretic peptide and troponin if cardiac etiology suspected Basic metabolic panel if dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities suspected |

| Prolonged ECG monitoring | Demonstrated utility in diagnosing arrhythmias that may be the cause of syncope; duration of monitoring is partially dependent on the frequency of syncopal episodes | Currently a lack of sufficient evidence as to whether long-term monitoring with implantable loop recorders decreases mortality |

| Stress testing | For patients who experience syncope during or after exertion | Syncope during exercise is likely cardiac, whereas syncope after exercise could be cardiac or reflex |

| Tilt table testing | Should be considered in individuals when the initial evaluation does not provide clear diagnosis of reflex syncope, orthostatic syncope, positional orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or psychogenic pseudosyncope | Tilt table testing may help differentiate syncope with abnormal movements from seizures; also may be beneficial to help patients recognize symptoms and learn physical maneuvers |

Overuse of testing and resources is common when evaluating patients with possible syncope. This was the focus of a study in which 1,020 hospitalists were given a scenario of textbook orthostatic hypotension: hydrochlorothiazide had recently been added to a 59-year-old man's blood pressure regimen. He had a syncopal episode after standing and recovered fully within two minutes. In the emergency department, orthostatic testing resulted in a drop in systolic blood pressure of 25 mm Hg, and ECG results were normal. Although medication change and discharge would be appropriate, 83% of respondents thought that further workup with additional testing (admission, echocardiography, stress testing, or tilt table testing) would be performed at their institutions.24

LABORATORY TESTING

Laboratory testing may be ordered based on the patient's history and physical examination findings. Examples include hemoglobin measurement due to a suspected hemorrhage, d-dimer assay if pulmonary embolism is considered, and pregnancy test when warranted. B-type natriuretic peptide and troponin levels should be considered if cardiac syncope is suspected; elevated results are associated with a higher risk of adverse outcomes.5,25

PROLONGED ECG MONITORING

Prolonged ECG monitoring may detect arrhythmias that could be the source of syncope, but the effect on mortality is not known. Among individuals with risk factors for cardiac syncope, inpatient or emergency department monitoring for more than 12 hours had a higher sensitivity for identifying arrhythmias than did shorter intervals. Following discharge, if the cause of syncope remains unknown, and a cardiac cause is still suspected, prolonged ECG monitoring is recommended.1 Monitoring for 15 days showed greater sensitivity for identifying causative arrhythmias than did shorter intervals.26 Table 6 shows ECG monitoring options for syncope.5,12,22,23

| Type of monitor | How it is used | Patient selection |

|---|---|---|

| Event monitor | Activated automatically or by patient | For individuals with weekly to monthly symptoms; can be used for 30 to 60 days |

| Holter monitor | Continuous monitoring with leads on chest | For individuals with daily episodes; records all data for 24 to 48 hours |

| Implantable loop recorder | Requires a minor surgical procedure; activated automatically or by patient | For individuals with infrequent, recurrent, or severe symptoms; can be used for 2 to 3 years |

| Patch monitor | Continuous monitoring for 3 to 14 days via a patch on the upper chest | For individuals with weekly symptoms; can be used for up to 14 days |

IMAGING STUDIES

Imaging studies are often ordered in the evaluation of syncope but are seldom beneficial. Regarding computed tomography of the head, numerous studies have demonstrated that in the absence of head trauma or neurologic abnormalities, it provides almost no benefit, and despite the lack of benefit, about 50% of patients presenting with syncope have computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the head.27 A systematic review found that less than 0.1% of those who had computed tomography of the head had findings that explained the syncopal episode.28 In the absence of physical examination findings consistent with symptomatic carotid stenosis, carotid ultrasonography is not recommended.1,18,29

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY AND STRESS TESTING

CAROTID SINUS MASSAGE

Carotid sinus massage may be diagnostic in individuals with syncope associated with carotid sinus hypersensitivity.5 History findings suggestive of carotid sinus hypersensitivity include onset of symptoms with head turning, shaving, or wearing tight collars and in those with a history of neck surgery or radiation. Carotid sinus syndrome is diagnosed if the carotid sinus massage reproduces symptoms and produces bradycardia or hypotension. This is performed in a setting in which continuous ECG monitoring and beat-to-beat blood pressure monitoring are available.5 Carotid sinus massage is a safe procedure in patients without critical carotid stenosis who have not had a recent transient ischemic attack or stroke. Neurologic complications are rare, and when they do occur, most are transient.30,31

TILT TABLE TESTING

There is considerable debate about the utility of tilt table testing.32,33 If the diagnosis of reflex syncope is highly likely based on the history and physical examination, tilt table testing is not needed, although it may be beneficial if this diagnosis is in doubt. Additionally, it may help to diagnose delayed orthostatic hypotension, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or psychogenic pseudosyncope.1,5,19

Risk Stratification and Disposition

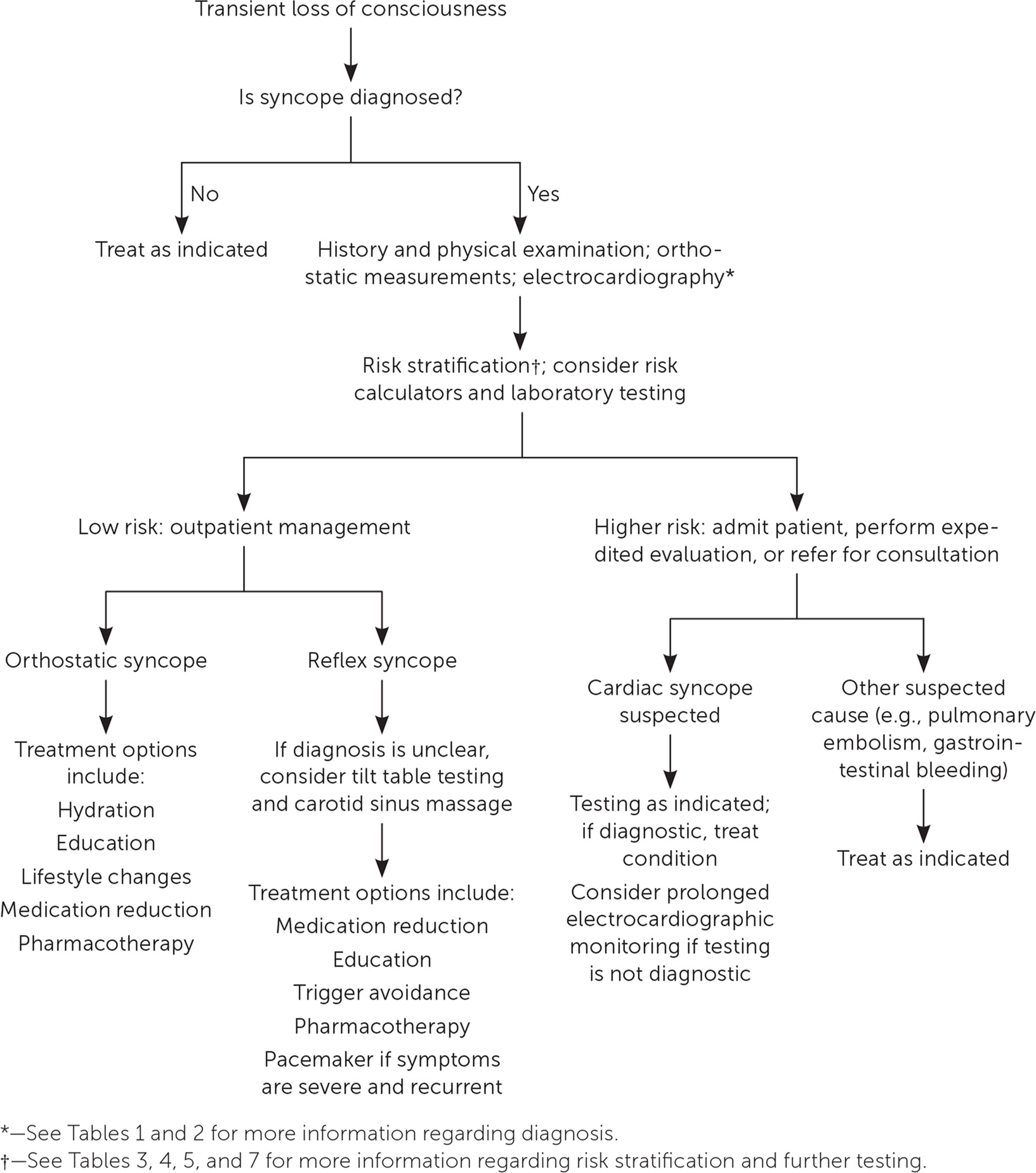

The decision to admit a patient with syncope is based on whether the initial assessment clearly identifies a low-risk condition or a higher-risk condition (Figure 1).1,5,8,12 Although 30% to 50% of people presenting to the emergency department with syncope are admitted to the hospital, mortality is 1.4% at 30 days and 7% after one year.34,35 Patients with a clear diagnosis of reflex or orthostatic syncope who are low risk can be discharged.1,5 Individuals who are not clearly at low risk should be admitted or observed (i.e., in the emergency department or syncope unit, if available).1,5 Most commonly, these are patients who may have cardiac syncope or an underlying condition that warrants treatment (e.g., gastrointestinal bleeding, pulmonary embolism).5

Risk stratification scores have not been shown to be superior to physician judgment, but they can be used to help determine a patient's risk.5,36 A recent systematic review concluded that the Canadian Syncope Risk Score was the most accurate scoring tool for classifying individuals as being at low or high risk of adverse outcomes within 30 days.37 In a validation study of the tool, no patients (n = 3,819) classified as low or very low risk had ventricular arrhythmia or died within 30 days.38 Components of the assessment include ECG findings, physician diagnosis, predisposition to vasovagal symptoms, history of heart disease, systolic blood pressure, and troponin level (Table 7).39

| Category | Comments | Points |

|---|---|---|

| Predisposition to vasovagal symptoms | Triggered by being in warm/crowded place, prolonged standing, fear, emotion, or pain | −1 |

| History of heart disease | Coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation or flutter, heart failure, valvular disease, nonsinus rhythm | 1 |

| Systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg or > 180 mm Hg | On any reading | 2 |

| Elevated troponin levels | > 99th percentile of normal population | 2 |

| Abnormal QRS axis | < 30 or > 100 degrees | 1 |

| QRS duration > 130 ms | — | 1 |

| Corrected QT interval > 480 ms | — | 2 |

| Emergency department diagnosis | Vasovagal syncope | −2 |

| Cardiac syncope | 2 | |

| Neither | 0 |

Treatment

CARDIAC SYNCOPE

The treatment of cardiac syncope is directed at the underlying etiology. A structural etiology may require procedural intervention. Arrhythmic etiology may be treated with medication, cardiac pacing, catheter ablation, or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.5

REFLEX SYNCOPE

Education and reassurance are the primary interventions for reflex syncope. The patient should avoid triggers of situational syncope, and onset of the prodrome should prompt changes in position or environment. Physical countermeasures, such as isometric muscle contractions, may avert an episode, particularly in patients who are younger than 60 years and have a prolonged prodrome.5

Medication changes and cardiac pacing may be considered in individuals who have recurrent syncopal episodes despite lifestyle changes. Stopping or reducing the dosage of blood pressure medications, alpha blockers, and vasodilators may reduce syncopal episodes.5,40 Fludrocortisone, which increases plasma volume, may reduce syncopal episodes in younger individuals with baseline low blood pressure. Midodrine, an alpha agonist, has some evidence of effectiveness but should be avoided in those with hypertension, heart failure, or urinary retention.1,41 [corrected] Only weak evidence indicates that the antidepressants fluoxetine and paroxetine may decrease syncopal episodes.1,42 Patients who have frequent, severe episodes of reflex syncope with documented asystole may benefit from placement of a dual chamber pacemaker.5,43

ORTHOSTATIC SYNCOPE

First-line treatment of orthostatic syncope is education and reassurance. The patient should avoid triggers such as a rapid movement from supine to standing. Adequate hydration and salt intake are recommended, and stopping offending medications should be considered. Physical countermeasures, support stockings, abdominal binders, and elevating the head of the patient's bed more than 10 degrees may help. If symptoms persist, midodrine and fludrocortisone may help.1,5

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Runser, et al.9; Gauer44; and Miller, et al.45

Data Sources: Key sources were Essential Evidence Plus, PubMed, the Cochrane database, Turning Research into Practice database, DynaMed, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. An initial PubMed search, limited to randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and guidelines from the past five years, was completed using the term syncope. Numerous other queries were completed in PubMed, limited to reviews, systematic reviews, guidelines, clinical trials, and randomized controlled trials; key terms included orthostasis, electrocardiogram/syncope, carotid sinus massage, tilt table testing, syncope risk scoring, and implantable loop recorder. In addition to the research of articles from the past five years, multiple longer and less-restrictive searches were completed. Search dates: September through November 2022.