Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(11):1961-1968

A more recent article on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is available.

Patient information: See related handout on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, written by the authors.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is a common condition associated with metabolic syndrome. It is the most common cause of elevated liver enzymes in U.S. adults, and is diagnosed after ruling out other causes of steatosis (fatty infiltration of liver), particularly infectious hepatitis and alcohol abuse. Liver biopsy may be considered if greater diagnostic and prognostic certainty is desired, particularly in patients with diabetes, patients who are morbidly obese, and in patients with an aspartate transaminase to alanine transaminase ratio greater than one, because these patients are at risk of having more advanced disease. Weight loss is the primary treatment for obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Medications used to treat insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and obesity have been shown to improve transaminase levels, steatosis, and histologic findings. However, no treatments have been shown to affect patient-oriented outcomes.

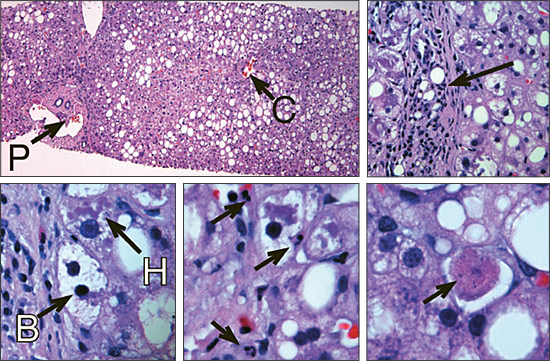

Formerly called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease now refers to a spectrum of diseases of the liver ranging from steatosis (i.e., fatty infiltration of the liver) to NASH (i.e., steatosis with inflammation and hepatocyte necrosis; Figure 1) to cirrhosis. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is the most common cause of elevated liver enzymes in adults in the United States1 and the most common cause of cryptogenic cirrhosis, which is cirrhosis that cannot be explained by hepatitis, alcohol abuse, toxin exposure, autoimmune disease, congenital liver disease, vascular outflow obstruction, or biliary tract disease.2 In the United States, estimates of the prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease range from 16 to 23 percent.3 However, in a recent population-based study, 31 percent of the 2,287 participants had steatosis diagnosed by nuclear magnetic spectroscopy.4 Patients who used alcohol were included in these numbers, but there was no difference in steatosis between patients using alcohol and patients who did not use alcohol. The prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease becomes greater with increasing body weight. Two thirds of patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg per m2 or greater, and more than 90 percent of patients with a BMI greater than 39 kg per m2, have steatosis.1 In the United States, up to 8.6 million persons who are obese may have steatohepatitis.1

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Although treatment of metabolic syndrome with statins, metformin (Glucophage), glitazone medications, and lifestyle changes may improve histologic and physiologic endpoints in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, use of these medications is not recommended solely as a treatment for this disease. | C | 13–17,20,21 |

| Weight loss should be approximately 1 to 2 lb (0.45 to 0.90 kg) per week; more rapid weight loss, particularly following bariatric surgery, may worsen nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. | C | 5 |

| Statins have not been shown to be harmful in patients with elevated transaminase levels associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. If statins are indicated for treatment of dyslipidemia, transaminase levels should be monitored closely. | C | 29–32 |

| Biopsy should be considered in individuals at increased risk of more advanced liver disease and in those for whom lifestyle changes do not result in normalization of transaminase levels if accurate diagnosis and prognosis are desired and the risks of biopsy are deemed acceptable. | C | 3,5 |

Nonalcoholic f atty liver disease has been associated with metabolic syndrome in observational studies and has been described as the hepatic component of this syndrome. The most common risk factors for the development of steatosis are obesity, diabetes, and hypertriglyceridemia. Other causes include toxins, medications, and inborn errors of metabolism (Table 1).5

| Disorders of lipid metabolism |

| Insulin resistance (metabolic syndrome [i.e., obesity, diabetes, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension]), lipoatrophy |

| Medications (amiodarone [Cordarone], diltiazem [Cardizem], highly active antiretroviral therapy, steroids, tamoxifen [Nolvadex]) |

| Refeeding syndrome |

| Severe weight loss (jejunoileal bypass, gastric bypass, starvation) |

| Total parenteral nutrition |

| Toxic exposure (e.g., organic solvents) |

Diagnosis

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Numerous conditions cause liver enzyme elevation and steatosis. Table 2 lists the more common causes of elevated liver enzymes and their corresponding historical, physical, and laboratory findings.

| Diagnosis | Steatosis present? | Alcohol abuse? | History | Physical findings | Other laboratory findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fatty liver | Yes | No | Type 2 diabetes, increased body mass index, hyperlipidemia | Obesity, often asymptomatic | Total bilirubin normal, albumin normal, AST/ALT usually < 1:1 |

| Alcohol | Yes | Yes | Alcohol use > 20 to 30 g per day (1.5 to 2 standard drinks) | Hepatomegaly, right upper quadrant tenderness | γ-glutamyltransferase usually two times normal, transaminase evels usually < 300 U per L, AST/ALT ≥ 1:1 |

| Autoimmune | No | No* | Type 1 diabetes, Graves' disease, ulcerative colitis, vasculitis, Sjögren's disease | Increased incidence in women (4:1) | Hypergammaglobulinemia; positive antinuclear antibody, Rh factor, antismooth muscle Abs, antiliver and kidney microsomal Abs, and Abs to soluble liver antigens |

| Viral hepatitis | No† | No* | Risk factors: illicit injection drug use, risky sexual behaviors, transfusions | Right upper quadrant tenderness, jaundice | Transaminase levels often ≥ 1,000 U per L in acute cases; lower in chronic states, elevated bilirubin (variable), AST/ALT < 1:1, positive viral serologies, positive immunoglobulin M antihepatitis B core (antigen), positive hepatitis C RNA, positive antihepatitis C Abs |

| Medication induced | Yes | No* | Increased transaminase levels after starting medication, resolves upon discontinuation | Variable | Transaminase levels often > 1,000 U per L in acute cases |

| Hemochromatsis | No | No* | Family history | Increased skin pigmentation, hepatomegaly, testicular atrophy, decreased libido, fatigue, cardiomyopathy | Increased serum ferritin, transferrin saturation > 45 percent, hepatic iron index > 1.9 |

The diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease requires exclusion of alcoholic liver disease and viral hepatitis (Figure 2). Although many persons likely have a combination of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease requires that daily alcohol intake be less than 20 g per day for women and less than 30 g per day for men. This equates to two standard alcoholic drinks per day for men and 1.5 standard alcoholic drinks per day for women. A standard drink contains 14 g of alcohol (e.g., 12 oz of beer, 5 oz of wine, or 1.5 oz of spirits).

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Most patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease are asymptomatic, but some may complain of fatigue and right upper quadrant abdominal fullness or pain. Up to 50 percent of patients with this disease have hepatomegaly.5 Patients with cirrhosis from nonalcoholic fatty liver disease will have findings similar to patients with cirrhosis from other causes.

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Laboratory abnormalities often are the only sign of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The most common abnormal laboratory test results are elevated alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST), usually one to four times the upper limits of normal.5 However, patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease may have normal transaminase levels. The ratio of AST/ALT usually is less than 1 (in alcoholic liver disease, this ratio typically will be greater than 2) but may increase as the severity of the liver damage increases.6 Alkaline phosphatase may be elevated up to twice the upper limit of normal5; γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) also may be elevated.

IMAGING STUDIES

Imaging studies assist in the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through identifying fatty infiltrate in the liver. Ultrasonography of the liver has a sensitivity of 82 to 89 percent and a specificity of 93 percent for identifying fatty liver infiltrate.7,8 If the pretest probability is 60 percent, 95 percent of patients with an ultrasound positive for steatosis will have a fatty liver, compared with 20 percent of those who have a normal ultrasound. Computed tomography is no more sensitive than ultrasonography and is more expensive. However, it can identify other liver pathology (e.g., masses) more effectively. Imaging modalities (i.e., computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ultrasonography) cannot distinguish steatosis from steatohepatitis.9

LIVER BIOPSY

The role of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is controversial. Arguments against routine liver biopsy include the generally benign course of the disease in most cases, lack of established effective therapies, and risks of biopsy.5 Although liver biopsy generally is safe, transient pain occurs in 30 percent of patients, severe pain in 3 percent, and significant complications in fewer than 3 percent. The risk of death is 0.03 percent,10 but biopsy is the only reliable method of diagnosing NASH and determining the prognosis.5 Patients who are likely to have more advanced liver disease should be considered for biopsy. Risk factors for more advanced disease include diabetes, morbid obesity (BMI > 39 kg per m2), advanced age, and an AST/ALT ratio greater than 1.11 Biopsy also may be considered in individuals who have persistent elevations in liver enzymes despite lifestyle changes.3 The American Gastroenterological Association states that the decision to perform a liver biopsy in a patient with suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the timing of the biopsy must be individualized and should include the patient in the decision-making process.5

RECOMMENDED DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

The American Gastroenterological Association recommends that patients with suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease be questioned carefully about alcohol use. The initial laboratory evaluation should include ALT, AST, alkaline phosphatase, serum bilirubin, and albumin levels; a prothrombin time; and diagnostic tests for viral hepatitis (Figure 212). When alcohol use and other causes of liver disease are excluded by the clinical and laboratory evaluation, an imaging study (e.g., ultrasonography or computed tomography) should be performed.13

Treatment

Treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease focuses primarily on risk factors for atherosclerotic heart disease. Steatosis alone probably does not warrant treatment. Even in patients with NASH, there are only disease-oriented outcome data at this time. Because NASH has the potential to progress to cirrhosis, treatment of NASH may be considered, particularly in patients with more advanced disease on biopsy. Several treatments improve liver enzyme abnormalities, radiographic findings, and histologic disease progression (Table 314–27 ). To date, there are no data that demonstrate improvement in morbidity or mortality rates.

| Treatment | Comparison | Study type | Patient population | Number of patients | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss and exercise14 | No lifestyle intervention | Controlled trial | Body mass index > 25 kg per m2 and steatosis | 25 | Improvement in AST and ALT levels and steatosis. Histology improved ut not to statistical significance. |

| Orlistat (Xenical)15 | NA | Open label | Obese patients with NASH | 10 | Improvement in AST and ALT levels. Steatosis improved in six patients, and fibrosis improved in three patients. |

| Metformin (Glucophage) and diet16 | Diet | RCT | Patients without diabetes who have NASH | 36 | Metformin group had significant improvements in AST, ALT, and fatty infiltrate levels. Improvement in liver inflammation was not statistically significant. |

| Rosiglitazone (Avandia)17 | NA | Open label | Patients with or without diabetes who have NASH | 30 | Significant improvement in liver fat content and AST and ALT levels |

| Pioglitazone (Actos)18 | NA | Open label | Patients without diabetes who have NASH | 18 | Significant decrease in AST, ALT, insulin, and C-peptide levels. Significant improvements in steatosis and histology |

| Gemfibrozil (Lopid)19 | Placebo | RCT | Patients with NASH | 46 | Improvement in AST, ALT, and GGT levels |

| Atorvastatin (Lipitor) and UDCA20 | UDCA | Open label | Patients with NASH (those with hyperlipidemia were placed in the atorvastatin group) | 44 | Patients in the atorvastatin group experienced decreased steatosis and improvement in AST, ALT, alkaline phosphatase, and GGT levels. UDCA group had improvement only in ALT and GGT levels. |

| Pravastatin (Pravachol)21 | NA | Open label | Patients with NASH | 5 | Improvement in liver histology and liver enzyme levels |

| UDCA22 | Placebo | RCT | Patients with NASH | 166 | No significant change in steatosis, necroinflammation, or fibrosis |

| Vitamin E23 | NA | Open label | Obese children with elevated transaminase levels and fatty liver | 11 | Normalization of AST and ALT levels during treatment |

| Vitamin E and lifestyle modifications24 | Vitamin E | RCT | Patients with NASH | 16 | Improvement in liver enzymes in both groups, but no additional benefit with vitamin E |

| Vitamin E(1,000 IU daily) and vitamin C (1,000 mg daily)25 | Placebo | RCT | Patients with NASH | 49 | Posttreatment liver biopsy showed decreased fibrosis in treatment group, but no improvement in inflammatory activity or ALT level. |

| Betaine26 | Placebo | RCT | Patients with NASH | 191 | Significant improvements in steatosis, hepatomegaly, and AST, ALT, and GGT levels |

| Betaine27 | NA | Open label | Patients with NASH | 10 | AST and ALT levels improved. Improvement in histology |

Weight loss and exercise have been shown to reduce liver enzyme levels and steatosis in children and adults who are obese.13,28 In a controlled trial,14 25 obese patients with fatty liver were divided into a treatment group (n = 15) that followed a restricted diet and exercise program and a control group (n = 10) that did not make any lifestyle changes. The treatment group had significant improvement in liver enzyme levels and steatosis. Pre- and postintervention biopsies were obtained and showed improvement in the treatment group, but not to statistical significance.14 In an open-label trial15 of 10 patients with biopsy-proven NASH, six months of treatment with orlistat (Xenical) resulted in a mean weight loss of 23 lb (10.4 kg) and significant decreases in ALT and AST levels; steatosis improved in six patients, and fibrosis improved in three patients. Rapid weight loss, particularly following bariatric surgery, may acutely worsen NASH. Weight loss should be approximately 1 to 2 lb (0.45 to 0.90 kg) per week.5

Treatment of insulin resistance has improved disease-oriented outcomes in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. In a randomized controlled trial,16 patients with NASH who did not have diabetes who received metformin (Glucophage) had significant reductions in AST and ALT levels and decreased hepatic steatosis. Rosiglitazone (Avandia) improved steatosis, AST, ALT, and histology17; pioglitazone (Actos) caused significant decreases in ALT, AST, insulin, and C-peptide levels; steatosis decreased and liver histology improved.18 None of these studies evaluated symptoms, morbidity, or mortality rates.

Medications for treating hyperlipidemia also have improved biochemical and histologic findings in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. In a randomized controlled trial,19 gemfibrozil (Lopid) resulted in lower AST, ALT, and GGT levels than placebo. In another study,20 atorvastatin (Lipitor), in a dosage of 10 mg per day, was given to 27 patients with NASH; AST and ALT levels decreased significantly, and liver fat content decreased. A small study21 assessing the effects of pravastatin (Pravachol) on patients with NASH showed improvement in liver histology and liver enzymes. There is no evidence that improving biochemical measures reduces morbidity or mortality rates.

Physicians may be hesitant to prescribe statins to patients with liver function abnormalities. However, modest elevation of liver enzyme levels should not preclude the use of statins in patients for whom they are otherwise indicated. In a recent study,29 342 patients with hyperlipidemia and elevated liver enzymes were prescribed a statin, and 2,245 patients with elevated liver enzymes were not prescribed a statin. After six months of treatment, there were no differences between the two groups in the incidence and degree of liver enzyme elevations. Patients were excluded from this study if they had a history of alcohol abuse or viral hepatitis. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute clinical advisory on the use and safety of statins states that modest transaminase elevations (less than three times the upper limits of normal) are not thought to represent a contraindication to initiating, continuing, or advancing statin therapy, as long as patients are monitored carefully.30 The National Cholesterol Education Program31 states that there is no evidence that statins are harmful in patients with fatty liver caused by obesity. Their use in persons with various forms of chronic liver disease depends on clinical judgment that balances proven benefit against risk. When starting statin therapy in a patient with chronic liver disease, the initial dose should be low, and liver enzyme levels should be checked in two weeks and then monthly for the first three months. If the transaminase levels increase to two times the baseline value, statin therapy should be discontinued.32

Medications that are believed to protect hepatocytes have been assessed for treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ursodeoxycholic acid was no more effective than placebo in improving enzyme levels and steatosis.22 Liver histology was similar in the two groups. In one trial,23 vitamin E resulted in normalization of ALT levels in 11 obese children. A more recent study24 comparing vitamin E and lifestyle modification with lifestyle changes alone showed no difference between the two groups. In a randomized controlled trial25 of patients with NASH, a combination of vitamin C (1,000 mg per day) and vitamin E (1,000 IU per day) improved fibrosis but not necroinflammatory activity or ALT levels compared with placebo. In addition, a meta-analysis33 found an increase in all-cause mortality with high-dose vitamin E.

Betaine, a nutritional supplement that is a component of the metabolic cycle of methionine, raises S-adenosylmethionine levels, which may reduce hepatic steatosis. An eight-week trial26 of betaine supplementation in patients with NASH compared with placebo showed reductions in ALT, AST, and GGT levels, and steatosis in the treatment group. In another trial,27 10 patients with NASH were treated with betaine for a year; ALT and AST levels improved, and follow-up biopsies demonstrated improved histology.

Prognosis

The prognosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease depends upon the extent of liver damage. Steatosis alone generally has a benign course, and progression to cirrhosis is rare. Although some cases of NASH appear to progress to cirrhosis, data are limited regarding how common that progression is.5 Existing data largely consist of small studies in highly selected populations in which the incidence of progression is likely higher than in the general population.34,35 A recent population-based study36 of 420 patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease showed that patients with this disease had higher mortality than the general public (mortality ratio, 1.34), but not to the degree noted in studies of selected patients in referral centers. Risk factors for more severe liver disease include diabetes, increasing weight, older age, and an AST/ALT ratio of greater than 1.11

Final Comment

There are no data about the effects of treatment on mortality rates related to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Several treatments have demonstrated improvement in liver enzyme levels, steatosis, and histology. However, patient-oriented outcomes data are not available. Further investigations, particularly those focusing on morbidity and mortality rates, are necessary before these treatments should be prescribed. In the meantime, physicians should recommend regular exercise, gradual weight loss, and appropriate treatment of risk factors for cardiovascular disease, particularly hyperlipidemia and diabetes.