This is an updated version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(9):603-612

Related letter: NAFLD in Children and Adolescents

Related letter: Updated Statistics for Liver Biopsy Risk

Patient information: See related handout on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

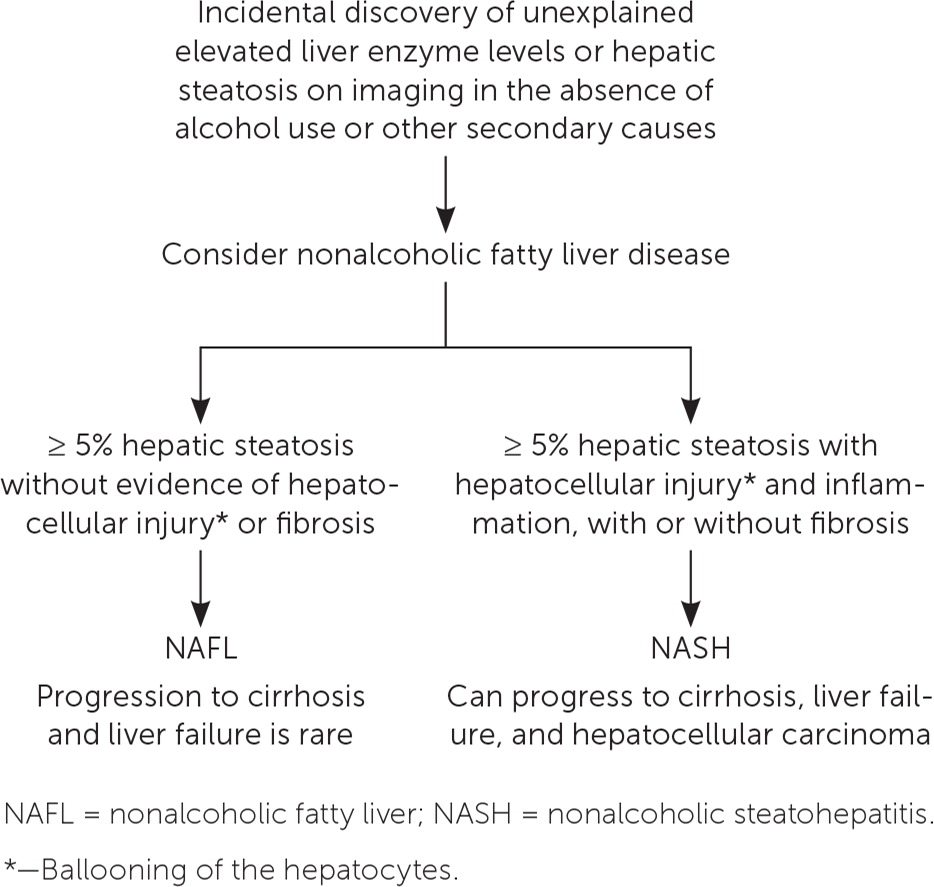

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common form of liver disease in the United States, affecting up to 30% of adults. There are two forms of NAFLD: nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), defined as 5% or greater hepatic steatosis without hepatocellular injury or fibrosis, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), defined as 5% or greater hepatic steatosis plus hepatocellular injury and inflammation, with or without fibrosis. Individuals with obesity are at highest risk of NAFLD. Other established risk factors include metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Although NAFLD is common and typically asymptomatic, screening is not currently recommended, even in high-risk patients. NAFLD should be suspected in patients with elevated liver enzymes or hepatic steatosis on abdominal imaging that are found incidentally. Once other causes, such as excessive alcohol use and hepatotoxic medications, are excluded in these patients, risk scores or elastography tests can be used to identify those who are likely to have fibrosis that will progress to cirrhosis. Liver biopsy should be considered for patients at increased risk of fibrosis and when other liver disorders cannot be excluded with noninvasive tests. Weight loss through diet and exercise is the primary treatment for NAFLD. Other treatments, such as bariatric surgery, vitamin E supplements, and pharmacologic therapy with thiazolidinediones or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues, have shown potential benefit; however, data are limited, and these therapies are not considered routine treatments. NAFL typically follows an indolent course, whereas patients with NASH are at higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and end-stage liver disease.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) comprises a continuum of fatty liver disease that occurs in the absence of alcohol use or other secondary causes of hepatic steatosis. There are two manifestations of NAFLD (Figure 1).1 One is nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), which is defined as 5% or greater hepatic steatosis without evidence of hepatocellular injury or fibrosis. The other is nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which is defined as 5% or greater hepatic steatosis with hepatocellular injury and inflammation, with or without fibrosis.1

WHAT'S NEW ON THIS TOPIC

It is projected that 100 million people in the United States will have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by 2030, with direct medical costs of about $103 billion annually.

By 2030, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is predicted to become the leading indication for liver transplantation in U.S. adults, surpassing hepatitis C.

Differentiating NAFL from NASH is important because they have different prognoses. NAFL follows a more indolent course, whereas patients with NASH are at risk of progression from fibrosis to cirrhosis and development of hepatocellular carcinoma.

NAFLD is the most common form of liver disease in the United States and other developed countries, with rates in the adult population estimated to be between 10% and 30%.2 About one-third of people with NAFLD have NASH.3 The prevalence of NAFLD increases with age, and it is more common in males and those of Hispanic descent.4

Who Is at Risk of NAFLD?

| Established |

| Obesity (highest risk) |

| Metabolic syndrome (Table 2) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus |

| Emerging evidence |

| Genetic variation of the PNPLA3 gene |

| HIV |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Obstructive sleep apnea |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Although not all individuals with NAFLD are overweight,14 the prevalence of NAFLD is directly proportional to body weight, with 37% to 93% of those undergoing bariatric surgery having NAFLD and 26% to 44% having NASH.8 However, any of the components of metabolic syndrome (Table 215) increase the risk of NAFLD.2,15

| Presence of any three of these five criteria is diagnostic: |

| Blood pressure |

| ≥ 130 mm Hg systolic or ≥ 85 mm Hg diastolic, or antihypertensive pharmacotherapy needed in a patient with a history of hypertension |

| Fasting glucose level |

| ≥ 100 mg per dL (5.55 mmol per L) or pharmacotherapy needed for elevated glucose level |

| HDL cholesterol level |

| < 50 mg per dL (1.29 mmol per L) in women or < 40 mg per dL (1.04 mmol per L) in men, or pharmacotherapy needed for reduced HDL cholesterol level |

| Triglyceride level |

| ≥ 150 mg per dL (1.69 mmol per L) or pharmacotherapy needed for elevated triglyceride level |

| Waist circumference |

| ≥ 35 in (89 cm) in women or ≥ 40 in (102 cm) in men |

For example, some studies suggest that 33% to 66% of patients with type 2 diabetes develop NAFLD, often accompanied by advanced fibrosis. Likewise, those with NAFLD are at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes. This bidirectional relationship makes the data on prevalence difficult to interpret because each can occur concurrently.9,10 In patients with NAFLD, having type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for progression to NASH, cirrhosis, and death, and poor glycemic control is also associated with poorer outcomes.2

Dyslipidemia is another metabolic risk factor for NAFLD. A study of 44,000 patients with dyslipidemia found the prevalence of NAFLD was 54% in this population, and this increased to 78% among those with the highest triglyceride to high-density–lipoprotein cholesterol ratios.11

Genetic factors are also involved in the risk of NAFLD. A study of 339 adults found that those with NAFLD who had the high-risk allele of the patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 (PNPLA3) gene had a twofold greater risk of advanced fibrosis (P = .006).12 The PNPLA3 gene is responsible for making a protein found in adipocytes and hepatocytes.

A 2019 review showed that obstructive sleep apnea is associated with more severe forms of NAFLD, and treating the apnea may improve associated liver injury.13 Higher rates of NAFLD are also observed in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome or hypothyroidism. Low thyroid function may worsen the progression of liver damage, whereas thyroid replacement therapy may improve liver function.13

Does Routine Screening of Asymptomatic Adults at Risk of NAFLD Improve Health?

Routine screening for NAFLD is not recommended, even in high-risk adults, because of uncertainties surrounding diagnostic tests and treatment options, and the lack of knowledge related to the long-term benefits and cost-effectiveness of screening. However, physicians should be alert for incidental findings suggestive of NAFLD in high-risk patients and initiate prompt evaluation when such findings are noted.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Routine screening is not recommended in the United States, even in high-risk patients, because liver enzyme levels are often normal in patients with NAFLD. Additionally, screening tools such as liver ultrasonography are not reliable at the low hepatic steatosis levels (less than 20%) often seen in early NAFLD.1

A 2015 cost-effectiveness analysis compared no screening with one-time ultrasound screening in a hypothetical cohort of 50-year-olds with type 2 diabetes. Participants with NASH received pioglitazone (Actos; 30 mg daily) to prevent cirrhosis. Those who were screened had a 1.32% decrease (10.22% to 8.90%) in cirrhosis and a 0.61% decrease (5.12% to 4.51%) in liver-related deaths compared with those who were not screened. However, in addition to the small reductions in cirrhosis and death, there was also a small reduction in quality-adjusted life-years because of weight gain, the most common adverse effect of pioglitazone therapy.16

What Is the Characteristic Presentation of NAFLD?

Except in late-stage disease when patients may have manifestations of overt hepatic insufficiency, there are no typical or characteristic symptoms of NAFLD. Rather, patients are often asymptomatic, and elevated liver enzymes or evidence of hepatic steatosis is incidentally found on testing performed for unrelated reasons. Occasionally, patients with NAFLD report fatigue, abdominal right upper quadrant fullness or pain, or pruritus.6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Abnormal findings on liver function tests can be clues to the presence of NAFLD. Normal alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels are typically defined as 0 to 35 U per L (0 to 0.58 μkat per L).17 Hepatic steatosis caused by excessive alcohol use is often associated with an AST:ALT ratio greater than 1.5, whereas patients with NAFLD tend to have a ratio less than 0.8, especially early in the disease. However, as NAFLD progresses to NASH with fibrosis, the AST:ALT ratio increases.18

What Is Included in the Initial Evaluation of a Patient with Suspected NAFLD?

The first step is to obtain a detailed history to exclude other causes of hepatic steatosis such as alcohol use or exposure to hepatotoxic medications. If these are excluded, the next step is to test for hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C virus antibody and measure ferritin, iron, lipid, and fasting glucose or A1C levels. Abdominal ultrasonography is the first-line imaging test for patients with suspected NAFLD and should be ordered if not already performed. If the test or ultrasound results point to alternative or coexisting causes of liver disease, additional testing should be performed.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

| Amiodarone |

| Aspirin |

| Chemotherapy drugs (fluorouracil, tamoxifen, irinotecan [Camptosar], cisplatin, asparaginase [Erwinaze]) |

| Cocaine |

| Glucocorticoids |

| Methotrexate |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Tetracyclines |

| Valproic acid |

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends assessing patients with suspected NAFLD for metabolic risk factors and obtaining lipid and fasting glucose or A1C levels.21 Testing for hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis C virus antibody and measurement of ferritin and iron are also recommended because chronic viral hepatitis and hereditary hemochromatosis are common causes of chronic liver disease that are found incidentally.1 Testing should be considered for less common alternative or coexisting causes of chronic liver disease (Table 422) as indicated based on clinical findings.1,23

| Cause | Clinical features | Laboratory evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency | Hepatomegaly and elevated liver enzyme levels | Alpha1-antitrypsin level, phenotyping, and liver biopsy |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | More common in women and in people with a history of thyroid disease | Antinuclear antibody, smooth muscle antibody, and liver/kidney microsomal antibody testing |

| Hereditary hemochromatosis | Bronze diabetes, arthritis, congestive heart failure, impotence, and family history | Complete blood count, ferritin level, transferrin saturations, genetic testing (HFE gene), liver biopsy with staining for iron, and magnetic resonance imaging |

| Wilson disease | Neurologic and psychological presentation in addition to liver disease at a young age (younger than 40 years) and family history | 24-hour urinary copper measurement, ceruloplasmin level, liver biopsy, and genetic testing |

A 2011 meta-analysis concluded that ultrasonography is the imaging test of choice in the evaluation of patients with suspected NAFLD because of its low cost, safety, and accessibility, although sensitivity and specificity of ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging are similar.24 A 2017 retrospective study of 352 patients with chronic liver disease found that combining standard ultrasound with various scoring systems (Hamaguchi score, ultrasound fatty liver index, or hepatorenal steatosis index) increases sensitivity and specificity for detection of hepatic steatosis.25,26 It should be noted that when ultrasonography is performed, sensitivity and specificity are higher at greater levels of fat infiltration.

What Noninvasive Testing Is Available to Determine Which Patients with NAFLD Are at High Risk of Fibrosis?

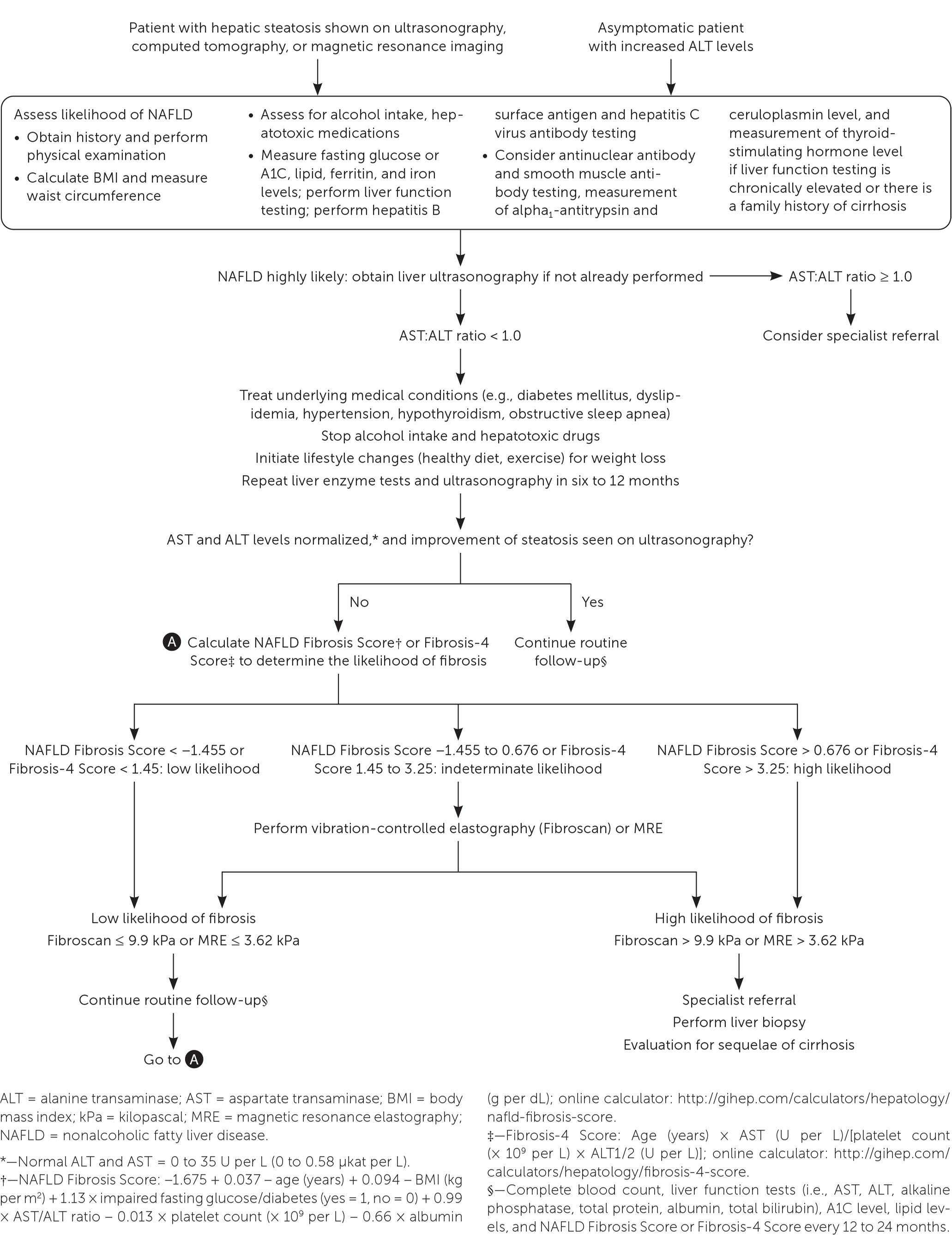

Clinical decision aids, such as the NAFLD Fibrosis Score (http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/nafld-fibrosis-score) and the Fibrosis-4 Score (http://gihep.com/calculators/hepatology/fibrosis-4-score), and liver stiffness measurements using vibration-controlled elastography (Fibroscan) or magnetic resonance elastography are clinically useful noninvasive tools for identifying patients with NAFLD that has a higher likelihood of progressing to fibrosis or cirrhosis. Table 5 summarizes these noninvasive tests.27–30 Figure 2 is an algorithm for the evaluation of patients with suspected NAFLD.1,22,31,32

| Test | Parameters | Cutoff and interpretation | Pros and cons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive for advanced fibrosis | Negative for advanced fibrosis | |||

| AST:ALT ratio | AST, ALT | ≥ 1.0 (sensitivity = 82%; PPV = 48%) | < 1.0 (specificity = 72%; NPV = 93%) | Best at excluding advanced fibrosis (as opposed to mild disease) because of lower specificity (44%) in patients with normal ALT levels |

| Fibrosis-4 Score* | Age, platelets, AST, ALT | > 3.25 (specificity = 98%; PPV = 80% to 85%) | < 1.45 (sensitivity = 82%; NPV = 92% to 95%) | Specificity is high in those with normal or abnormal ALT levels (77% and 72%, respectively) |

| NAFLD Fibrosis Score† | Age, blood glucose, body mass index, platelets, albumin, AST: ALT ratio | > 0.676 (specificity = 97% to 98%; PPV = 82% to 88%) | < −1.455 (sensitivity = 82% to 90%; NPV = 88% to 92%) | Better at excluding advanced fibrosis because of lower specificity (57%) in patients with normal ALT levels |

| Magnetic resonance elastography | Probe placed on the patient's back emits low-frequency vibrations that can be measured to quantify fibrosis | > 3.62 kPa (specificity = 83.2%; PPV = 61.8%) | ≤ 3.62 kPa (sensitivity = 82.5%; NPV = 93.5%) | Higher sensitivity at less fibrosis severity |

| Vibration-controlled elastography (Fibroscan) | Uses mild amplitude and low-frequency elastic shear T waves propagating through the liver, which is directly related to tissue stiffness | > 9.9 kPa (specificity = 77%; PPV = 46.5%) | ≤ 9.9 kPa (sensitivity = 95%; NPV = 98.7%) | Unreliable results in patients with body mass index > 36.65 kg per m2 if using the M probe |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Liver biopsy is the diagnostic standard for fibrosis in NAFLD. Although the mortality associated with liver biopsy is low, ranging from 0.01% to 0.3%, the invasiveness of the procedure and potential for serious complications such as major bleeding (0.1% to 4.6%) leads most clinicians to utilize noninvasive tests for initial evaluation.58,59,60 [updated]

Treatment guidelines consistently recommend that adults with NAFLD undergo risk stratification using the NAFLD Fibrosis Score or the Fibrosis-4 Score.1,18,19,30,35 A 2016 study demonstrated that these scores are better than other indices and as good as magnetic resonance elastography for predicting advanced fibrosis.27

If more advanced noninvasive testing is used, a 2019 systematic review and pooled analysis of 230 patients found that magnetic resonance elastography has a significantly higher diagnostic accuracy than vibration-controlled elastography, especially when identifying early (stage 1 or 2) fibrosis.28 Other studies have shown that the tests are comparable in identifying stage 3 disease (advanced fibrosis) or stage 4 disease (cirrhosis).29,30,36

When Should Liver Biopsy Be Considered in Patients with NAFLD?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) recommends biopsy when the etiology of liver disease is unclear and in those who are at increased risk of NASH or advanced fibrosis.1 For instance, liver biopsy should be considered in a patient with persistently elevated serum ferritin and transferrin levels, which may suggest hereditary hemochromatosis, especially if genetic testing is positive. Likewise, biopsy should be considered when high serum titers of autoantibodies are present in association with other features of autoimmune liver disease.1 A liver biopsy can also distinguish between NAFL and NASH (Figure 1).1

How Is NAFLD Treated?

Weight loss through diet and exercise is the primary treatment for NAFLD. Bariatric surgery, vitamin supplements, thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone), and glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues (liraglutide [Victoza]) may be beneficial for some patients, but there is insufficient evidence to support their use as first-line or primary treatments. Table 6 summarizes the treatment options for NAFLD.1,22

| Treatment | Liver enzyme levels | Liver histology | Evidence | 2018 AASLD guidance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight loss via diet and exercise | Improved | Improved | RCTs | Standard primary treatment for NAFLD |

| Bariatric surgery | Improved | Improved | Retrospective and prospective cohort studies | Consider foregut bariatric surgery in patients with NAFLD only when indicated based on obesity |

| GLP-1 analogue (liraglutide [Victoza]) | Improved | Improved | RCT | Premature to recommend as routine therapy |

| Thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone [Actos]) | Improved | Inconsistent | RCT | Limit use to patients with biopsy-proven NASH; may cause weight gain |

| Vitamin E | Improved | Improved | RCT | Consider in patients without diabetes mellitus who have biopsy-proven NASH; discuss the risks and benefits with patients |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of eight randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and a prospective trial demonstrated that a loss of 3% to 5% of total body weight is needed to improve hepatic steatosis, and a loss of 7% to 10% of total body weight is needed to improve the histopathologic abnormalities in the liver associated with NAFLD.1 A 2017 review of the association between the Mediterranean diet and NAFLD found that the Mediterranean diet consistently reduced liver fat independent of weight loss.37 The European Associations for the Study of the Liver, Diabetes, and Obesity recommend the Mediterranean diet for patients with NAFLD.38

Bariatric Surgery. Several prospective studies of disease-oriented outcomes found resolution of NASH after bariatric surgery. One of these studies reported that NASH resolved in 85% (95% CI, 75.8% to 92.2%) of the 109 participants within one year of bariatric surgery.39 Although bariatric surgery can be recommended for patients with NAFLD when indicated based on obesity, it is premature to consider bariatric surgery as an option to specifically treat NAFLD.1

Vitamin E. Because of its antioxidant potential, vitamin E has also been evaluated as a potential treatment for NAFLD. A large clinical trial showed that nearly all patients receiving 800 IU of vitamin E daily had histologic improvements of NASH (96% vs. 19% with placebo; P < .001).6 However, some studies have shown an association between vitamin E and an increased risk of prostate cancer and hemorrhagic stroke; one study demonstrated a reduction in thrombotic stroke.40–43 The AASLD recommends use of vitamin E in patients without diabetes who have biopsy-proven NASH only after discussing the risks and benefits with the patient.1

Omega-3 Fatty Acids. Because studies of omega-3 fatty acids have not demonstrated a therapeutic benefit, the AASLD and NICE recommend against using omega-3 fatty acids in the treatment of NAFLD.1,21 A 2017 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to recommend vitamin D as a treatment for liver disease; however, only four of the 16 trials specifically evaluated its use in NAFLD.44

Prescription Medications. Although no prescription medications have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat NAFLD, interventions should be aimed at treating the patient's comorbid metabolic conditions. For example, although statins do not treat NAFLD directly, they should be used to treat dyslipidemia in patients with NAFLD because these patients have an inherently higher risk of cardiovascular disease. The AASLD recommends use of a statin for dyslipidemia in these patients, noting that there is no increased risk of serious liver injury in those with NAFLD.1 NICE also recommends that statin medications be continued in patients with NAFLD and discontinued only if liver enzymes double within three months of initiation.21

In two RCTs, metformin did not lead to improvement in liver histology in patients with NAFLD. Thus, metformin should not be prescribed to patients with NAFLD in the absence of type 2 diabetes.1

The thiazolidinedione pioglitazone and the glucagon-like peptide-1 analogue liraglutide have shown some promise, although data are limited. In a trial involving 101 patients with prediabetes, 51% of patients taking pioglitazone had resolution of biopsy-proven NASH compared with 19% taking placebo (P < .001).45 In another trial, resolution of NASH was also achieved in more patients taking pioglitazone than those taking placebo (n = 247; 47% vs. 21%; P < .001).46 A more recent systematic review found a similar benefit.47 However, pioglitazone use increases the risk of weight gain and should not be used to treat NAFLD in patients without biopsy-proven NASH until further data are available.1

In a small RCT (n = 52), liraglutide demonstrated greater resolution of NASH compared with placebo (39% vs. 9%; P = .019).48 Several other studies have also found improvement in the histologic features of NAFLD with liraglutide therapy.47 Nonetheless, it is premature to recommend glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues such as liraglutide as routine treatment for NAFLD or NASH.1

What Monitoring Is Recommended for NAFLD?

Although there is no consensus on monitoring, it is reasonable for primary care clinicians to initiate intensive lifestyle changes and repeat liver enzyme measurements and ultrasonography in six to 12 months. If abnormalities persist and the patient is at low risk of fibrosis, the patient should be monitored every 12 to 24 months with a complete blood count; measurement of liver enzyme, lipid, and fasting glucose or A1C levels; and calculation of fibrosis risk scores (NAFLD Fibrosis Score or Fibrosis-4 Score). High-risk patients should be referred to a specialist.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

What Is the Prognosis for Those with NAFLD?

Most patients with NAFL will have a benign, nonprogressive disease course. Only 20% develop NASH, and 20% of those with NASH develop cirrhosis. Patients with a higher degree of fibrosis have a higher risk of death, mainly from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and end-stage liver disease.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Two cohort studies found that 80% of patients with NAFLD had no progression to NASH. Of those who developed cirrhosis, 31% progressed to hepatic decompensation. About 2% of patients with NAFLD developed hepatocellular carcinoma.52

A community-based study of 420 patients with NAFLD found that these patients had a 34% higher risk of death (standard mortality ratio = 1.34; 95% CI, 1.003 to 1.76; P = .03) than would be expected in the general population; the three main causes of death were cancer, ischemic heart disease, and liver disease.53 A study of 817 patients with NAFLD echoed these results (hazard ratio = 1.038; 95% CI, 1.036 to 1.041; P < .0001), with liver disease as the third leading cause of death after cardiovascular disease and malignancy.54 A meta-analysis also showed higher overall mortality in patients with NAFLD (odds ratio = 1.57; 95% CI, 1.18 to 2.10; P = .002).55 Further studies that stratified patients' risk using fibrosis scoring tools found higher disease-specific mortality in those with NASH, indicating that fibrosis is the most important predictor of long-term outcomes.56

When Should Patients with NAFLD Be Referred to a Specialist?

Referral to gastroenterology should be considered in patients who have a high likelihood of NASH fibrosis because of the presence of metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes, who have progression to fibrosis as indicated by an AST:ALT ratio greater than 1.0, who have an NAFLD Fibrosis Score or Fibrosis-4 Score showing high risk, who have abnormal results on noninvasive testing (magnetic resonance elastography or vibration-controlled elastography), or who have imaging or clinical evidence of cirrhosis.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

An AST:ALT ratio greater than 1.0 is concerning for other causes of liver disease or advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. One study determined that this cutoff ratio provided the best negative predictive value for advanced fibrosis.57 Based on expert opinion, referral should be considered for adults with fibrosis and cirrhosis because they may benefit from aggressive monitoring for esophageal varices, signs of decompensation of hepatic function (international normalized ratio, bilirubin level, and albumin level), and hepatocellular carcinoma or referral for liver transplantation.6,21

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Wilkins, et al.22 ; and Bayard, et al.14

Data Sources: A targeted PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, fatty liver disease, fatty liver, and NASH. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were POEMs, Cochrane reviews, clinical decision rules, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare reports, Guidelines.org, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: May 2019 through April 2020.

The authors thank Angela Buffington, PhD, ABPP-CN, LP, University of Minnesota Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, for assistance with proofreading and editing the manuscript.