Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(9):1078-1084

Patient information: See related handout on hives, written by the author of this article.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Urticaria involves intensely pruritic, raised wheals, with or without edema of the deeper cutis. It is usually a self-limited, benign reaction, but can be chronic. Rarely, it may represent serious systemic disease or a life-threatening allergic reaction. Urticaria has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 20 percent in the general population. It is caused by immunoglobulin E– and nonimmunoglobulin E–mediated mast cell and basophil release of histamine and other inflammatory mediators. Diagnosis is made clinically. Chronic urticaria is usually idiopathic and requires only a simple laboratory workup unless elements of the history or physical examination suggest specific underlying conditions. Treatment includes avoidance of triggers, although these can be identified in only 10 to 20 percent of patients with chronic urticaria. First-line pharmacotherapy for acute and chronic urticaria is nonsedating second-generation antihistamines (histamine H1 blockers), which can be titrated to larger than standard doses. First-generation antihistamines, histamine H2 blockers, leukotriene receptor antagonists, and brief corticosteroid bursts may be used as adjunctive treatment. More than one-half of patients with chronic urticaria will have resolution or improvement of symptoms within one year.

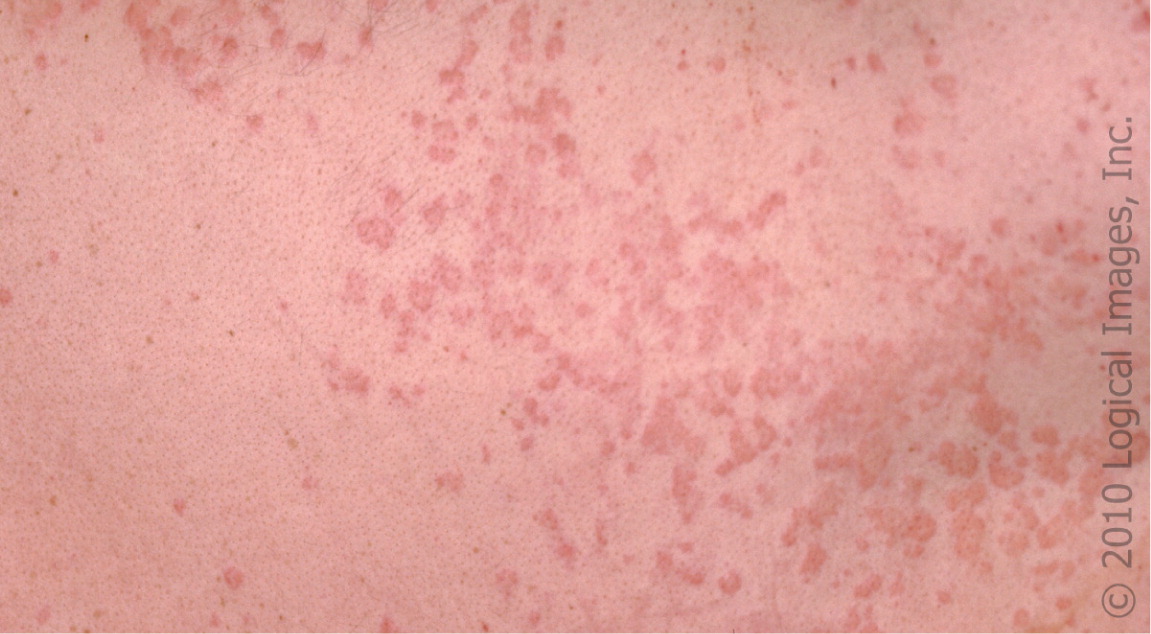

Urticaria is a common condition identified and treated in the primary care setting. It is characterized by well-circumscribed, intensely pruritic, raised wheals (edema of the superficial skin) typically 1 to 2 cm in diameter, although they can vary in size and may coalesce; they also can appear pale to brightly erythematous (Figures 1 through 3). Urticaria can occur with or without angioedema, which is a localized, nonpitting edema of the subcutaneous or interstitial tissue that may be painful and warm. It can cause marked impairment in work, school, and home functioning. Although typically benign and self-limited, urticaria and angioedema can be symptoms of anaphylaxis, or may indicate a medical emergency or, rarely, substantial underlying disease.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| An extensive workup is not recommended for diagnosing a cause of chronic urticaria. Additional testing can be done if presentation suggests underlying disease or specific causes requiring confirmation. | C | 1, 7, 9, 15 | A complete blood count with differential and measurement of erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level are recommended to rule out systemic disease. Various sources recommend urinalysis, measurement of thyroid-stimulating hormone level, and liver function testing to look for other causes. |

| Nonsedating antihistamines are the first-line treatment of urticaria and may be titrated to two to four times their normal dose, if necessary. | C | 1, 7, 16 | These are recommended over older antihistamines because of their adverse effect profiles. All histamine H1 blockers appear to be effective. There are few head-to-head effectiveness data. |

| The addition of a histamine H2 blocker to an H1 blocker may help in refractory cases of urticaria. | B | 1, 7, 16, 18 | Several studies have found at least a modest benefit, although the mechanism of this benefit is unclear. |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonists may be most useful in patients with cold urticaria or intolerance to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. | B | 21 | Several trials have shown benefit to using these medications with or without antihistamines, especially in the subpopulations listed. |

Urticaria can occur on any part of the skin. The lesions are round to polymorphic, and can rapidly grow and coalesce. Angioedema primarily affects the face, lips, mouth, upper airway, and extremities, but can occur in other locations. In both conditions, the onset of symptoms is rapid, usually occurring within minutes. Individual urticarial lesions typically resolve within 24 hours without treatment, although angioedema may take up to 72 hours.1 Usually there are no residual lesions remaining after symptom resolution, except for possible excoriations from itching.

Urticaria, with or without angioedema, can be classified as acute or chronic. In acute urticaria, although individual wheals resolve within hours, they can recur for up to six weeks, depending on the etiology. In chronic urticaria, flare-ups recur more days than not for more than six weeks. Often it is not apparent which cases will progress to chronic urticaria at initial presentation. Urticaria occurs across all age ranges and has a lifetime prevalence of approximately 20 percent in the general population, with the chronic form affecting 1 percent of the population.2

Etiology

Urticaria and angioedema are thought to have similar underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms, with histamine and other mediators being released from mast cells and basophils. The difference between the two conditions is whether the mast cells are in the superficial dermis, which results in urticaria, or in the deeper dermis and subcutaneous tissues, which produces angioedema. Immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediation of this histamine release is often ascribed, but non-IgE and nonimmunologic mast cell activation can also be a cause. Bradykinin-mediated increase in vascular permeability is another cause of angioedema associated with the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Chronic urticaria may have a serologic autoimmune component in some patients, including antibodies to IgE and the high-affinity IgE receptor. However, the exact mechanism of action and significance of these antibodies remain unclear.3,4

Several causes of urticaria have been identified (Table 1).5 Triggers often can be identified in patients with acute urticaria, although a specific trigger is found in only 10 to 20 percent of chronic cases.6 Common triggers include allergens, food pseudoallergens (i.e., foods or food additives that contain histamine or that may cause the release of histamine directly, such as strawberries, tomatoes, preservatives, and coloring agents), insect envenomation, medication, or infections.7–9 Urticaria can be caused by allergic reactions to medications, especially antibiotics, and through direct mast cell degranulation by some medications, including aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, radio-contrast dye, muscle relaxants, opiates, and vancomycin. Figure 4 shows an example of contact urticaria. Physical stimuli (e.g., heat, cold [Figure 5], vibration, pressure) and exercise or other triggers that raise the core body temperature (cholinergic urticaria [Figure 6]) can also cause urticaria in some patients, likely through direct mast cell activation.10

| Immunoglobulin E mediated |

| Aeroallergens |

| Contact allergen |

| Food allergens |

| Insect venom |

| Medications (allergic reaction) |

| Parasitic infections |

| Nonimmunoglobulin E mediated |

| Autoimmune disease |

| Cryoglobulinemia |

| Infections (bacterial, fungal, viral) |

| Lymphoma |

| Vasculitis |

| Nonimmunologically mediated |

| Elevation of core body temperature |

| Food pseudoallergens |

| Light |

| Medications (direct mast cell degranulation) |

| Physical stimuli (cold, local heat, pressure, |

| vibration) |

| Water |

Systemic disease is a relatively rare cause, with the exception of Hashimoto disease; thyroid autoimmunity may be associated with up to 30 percent of chronic urticaria cases.11 Other systemic illnesses that have been associated with urticaria or angioedema include mastocytosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis, hepatitis, and lymphoma.

Differential Diagnosis

Urticaria is often referred to as hives, but that term can have a variety of meanings in the general population. Common conditions that can be confused with urticaria are listed in Table 2.12,13 These conditions are diagnosed primarily by history and physical examination. Some conditions can produce urticarial lesions, but they have a different underlying pathophysiology, as well as prognosis and treatment. These include cutaneous mastocytosis (urticaria pigmentosa), urticarial vasculitis, cryoglobulinemia, and several rare disorders. These conditions may be distinguished based on differences in presentation. For example, cutaneous mastocytosis is noted for orange to brown hyperpigmentation of the lesions, urticaria limited to smaller diameters, and Darier sign (a wheal and flare reaction produced by stroking the lesion). Likewise, classic urticarial vasculitis is distinguished by individual wheals that last for more than 24 hours, are painful, and leave residual hyperpigmentation or purpura12 (Figures 7 and 8). However, the sensitivity of these characteristics may be low.14

| Condition | Distinguishing characteristics |

|---|---|

| Arthropod bites | Lesions last several days, insect exposure history |

| Atopic dermatitis | Maculopapular, scaling, characteristic distribution |

| Contact dermatitis | Indistinct margins, papular |

| Erythema multiforme | Lesions last several days, iris-shaped papules, target appearance, may have fever |

| Fixed-drug reactions | Offending drug exposure, not pruritic, hyperpigmentation |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | Lower extremity distribution, purpuric lesions, systemic symptoms |

| Morbilliform drug reactions | Maculopapular, associated with medication |

| Pityriasis rosea | Lesions last weeks, herald patch, “Christmas tree” pattern, often not pruritic |

| Viral exanthem | Not pruritic, prodrome, fever, maculopapular lesions, individual lesions last for days |

Evaluation

The initial workup for urticaria and angioedema is a history and physical examination to determine a possible etiology (Table 3). Patients should be asked about timing and onset of symptoms, associated symptoms (which may suggest anaphylaxis), likely triggers, medications and supplements (especially new or recently changed dosages), recent infections, and travel history. Physicians should perform a complete review of systems. Physical examination should include identifying and characterizing any current lesions, testing for dermatographism (urticaria, often linear, that forms with stroking or rubbing of unblemished skin), and checking for signs of systemic illness.

| Clinical clue | Possible etiology |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain, dizziness, shortness of breath, stridor, tachycardia | Anaphylaxis |

| Dermatographism | Physical urticaria |

| Food ingestion immediately before symptoms | Food allergy |

| Infectious exposure | Infection |

| Medication use or change | Medication allergy or direct mast cell degranulation |

| Physical stimuli | Physical urticaria (Figure 5) |

| Smaller wheals (1 to 2 mm), burning or itching, brought on by heat or exercise | Cholinergic urticaria (Figure 6) |

| Travel | Parasitic or other infection |

| Upper respiratory tract infection or urinary tract infection symptoms | Infection |

| Weight gain, cold intolerance | Hypothyroidism |

| Weight loss (unintentional) | Lymphoma |

| Wheals lasting more than 24 hours, burning, residual hyperpigmentation | Urticarial vasculitis (Figures 7 and 8) |

A broad laboratory workup has not been found to increase the likelihood of diagnosing a cause of urticaria.15 No workup is recommended for acute urticaria unless history or physical examination suggests underlying disease or a specific cause that needs to be confirmed or ruled out. For instance, presentation suggestive of urticarial vasculitis should prompt immediate biopsy. With chronic urticaria, all of the guidelines reviewed for this article recommend a complete blood count with differential and measurement of erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level to test for infection, atopy, and systemic illness, whereas measurement of thyroid-stimulating hormone level, liver function tests, and urinalysis are variously recommended.1,7,9 Such testing typically would be ordered after symptoms have been present for six weeks. As with acute urticaria, a broader workup for chronic urticaria is recommended only when there are suggestions of specific causes or underlying issues. Abnormalities in the initial testing are uncommon, but should be followed up when present. When history suggests a physical urticaria, challenge testing with the physical stimuli may be considered, but such testing often lacks validated challenge parameters.10

Treatment

The centerpiece of treatment is avoidance of known triggers. It is also recommended that patients avoid aspirin, alcohol, and possibly nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use because these may worsen urticarial symptoms. When avoidance is impossible, no trigger is identified, or symptomatic relief is still required despite avoidance, antihistamine medications are first-line pharmacotherapy. A variety of additional medications can be used when first-line antihistamines are not adequate.

ACUTE SYMPTOMS

Data on the treatment of acute urticaria are sparse; most available data are on treatment of chronic urticaria. Nonetheless, histamine H1 blockers are first-line therapy for acute urticaria. These include second-generation agents such as loratadine (Claritin), desloratadine (Clarinex), fexofenadine (Allegra), cetirizine (Zyrtec), and levocetirizine (Xyzal), which are relatively nonsedating at standard dosages and are dosed once per day. First-generation antihistamines such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl), hydroxyzine (Vistaril), chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton), and cyproheptadine are faster acting and some have parenteral forms, but also require more frequent dosing and have more adverse effects, including drowsiness, decreased reaction time, confusion, dizziness, impaired concentration, and decreased psychomotor performance. Older patients may be more susceptible to these effects. Because of the adverse effect profiles and the half-lives of the agents' antihistaminergic effects, the second-generation antihistamines are recommended as initial pharmacotherapy.1,7,16 However, head-to-head clinical trials are too sparse to clearly determine if one antihistamine is superior to another, given the ranges in individual responses to a specific medication. With more severe symptoms, first-generation H1 blockers may be used for their more rapid onset of action or parenteral forms.17 Psychomotor adverse effects should be discussed with patients before initiation of therapy.

Addition of histamine H2 blockers to therapy with H1 blockers has been shown to be modestly beneficial for acute symptoms.18 H2 blockers include cimetidine (Tagamet), famotidine (Pepcid), and ranitidine (Zantac). Limited data suggest that adding corticosteroids to antihistamines may yield a more rapid improvement and resolution of symptoms19; as such, prednisone or prednisolone (0.5 to 1 mg per kg per day) may be added for three to seven days, usually in a tapered dosage, especially for patients with severe symptoms.13,19

Treatment of acute angioedema is largely the same as treatment for urticaria, although corticosteroids may be recommended more often.13 However, angioedema of the larynx and massive angioedema of the tongue are medical emergencies because of airway obstruction risk, requiring intramuscular epinephrine and airway management. Patients who have had angioedema that threatened airway compromise should be prescribed epinephrine autoinjectors in sufficient numbers so that they will have one for home, work or school, and their car, as appropriate.

CHRONIC URTICARIA

A stepwise approach to treating chronic idiopathic urticaria, based on published treatment guidelines, is shown in Figure 9.1,7,16 Second-generation antihistamines are considered first-line therapy. For better symptom control, the medication should be dosed daily, rather than on an as-needed basis.20 Treatment guidelines suggest that if normal doses are not successful, titration up to two to four times the usual dose is the next step.1,7,16 With higher doses, there is greater possibility of adverse effects, which should be discussed with patients.

If symptoms remain uncontrolled, there are several options. The patient can be switched to a different second-generation H1 blocker and titrated as necessary. First-generation antihistamines may be added, especially at night, although such combination regimens have few published effectiveness data. H2 blockers may be added and have been shown to be at least modestly beneficial when used in conjunction with H1 blockers. A three- to 10-day tapered burst of oral corticosteroids (prednisone or prednisolone, up to 1 mg per kg per day) is sometimes used to get control of symptoms, although corticosteroids do not directly prevent mast cell degranulation,7,16,21 and long-term use is not recommended because of adverse effects.

There are data on the effectiveness of leukotriene receptor antagonists such as montelukast (Singulair) and zafirlukast (Accolate) in the treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria, especially in patients with cold urticaria or intolerance to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and a leukotriene receptor antagonist may be added if first-line agents are insufficient.21 The tricyclic antidepressant doxepin has significant H1 antihistaminergic properties and has been shown to be effective for urticaria in several small, randomized controlled trials, but it also is sedating and has anticholinergic adverse effects, as well as possible cardiac arrhythmia adverse effects.7,22 These various pharmacotherapy options can be added individually or layered sequentially to obtain control of symptoms.

If sufficient control still is not achieved, second-line agents including cyclosporine (Sandimmune), sulfasalazine (Azulfidine), hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil), tacrolimus (Prograf), and dapsone have shown some benefits. However, referral to a subspecialist for prescribing such medications may be preferred, depending on the physician's comfort level and experience with their administration.21 After symptoms are controlled adequately, patients should be maintained on the regimen (excluding corticosteroids) for at least three months before considering titrating down and discontinuing medications.

Prognosis

A prospective cohort study found that 35 percent of patients with chronic urticaria will be symptom-free within one year, with another 29 percent having some reduction of symptoms. Spontaneous remission occurred within three years in 48 percent of patients with idiopathic chronic urticaria, but in only 16 percent of those with physical urticaria.23

Data Sources: Initial PubMed search results were provided by American Family Physician. Repeat PubMed Clinical Queries using the term “urticaria” with each category and systematic review were performed throughout the writing process, starting on April 1, 2010, with the last search performed on July 1, 2010. Also searched were Bandolier, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (complete reviews), Effective Healthcare, National Guideline Clearinghouse, DynaMed, and UptoDate Online.