A more recent article on syncope is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(6):640-650

Related letter: Consider Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome in Patients with Syncope

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations to disclose.

Syncope is a transient and abrupt loss of consciousness with complete return to preexisting neurologic function. It is classified as neurally mediated (i.e., carotid sinus hypersensitivity, situational, or vasovagal), cardiac, orthostatic, or neurogenic. Older adults are more likely to have orthostatic, carotid sinus hypersensitivity, or cardiac syncope, whereas younger adults are more likely to have vasovagal syncope. Common nonsyncopal syndromes with similar presentations include seizures, metabolic and psychogenic disorders, and acute intoxication. Patients presenting with syncope (other than neurally mediated and orthostatic syncope) are at increased risk of death from any cause. Useful clinical rules to assess the short-term risk of death and the need for immediate hospitalization include the San Francisco Syncope Rule and the Risk Stratification of Syncope in the Emergency Department rule. Guidelines suggest an algorithmic approach to the evaluation of syncope that begins with the history and physical examination. All patients presenting with syncope require electrocardiography, orthostatic vital signs, and QT interval monitoring. Patients with cardiovascular disease, abnormal electrocardiography, or family history of sudden death, and those presenting with unexplained syncope should be hospitalized for further diagnostic evaluation. Patients with neurally mediated or orthostatic syncope usually require no additional testing. In cases of unexplained syncope, further testing such as echocardiography, grade exercise testing, electrocardiographic monitoring, and electrophysiologic studies may be required. Although a subset of patients will have unexplained syncope despite undergoing a comprehensive evaluation, those with multiple episodes compared with an isolated event are more likely to have a serious underlying disorder.

Syncope is a transient and abrupt loss of consciousness with complete return to preexisting neurologic function. The cumulative incidence of syncope is 3 to 6 percent over 10 years, and 80 percent of patients have their first episode before 30 years of age.1 The overall distribution of syncope is equal between men and women; however, women are more likely to have an event at the extremes of age. Compared with persons 50 to 59 years of age, the incidence increases two- and threefold, respectively, in persons 70 to 79 years of age and in persons 80 years or older.1 Population-based studies indicate that approximately 40 percent of adults have experienced syncope, with women being more likely to report a syncopal event.2 In the Framingham Heart Study, 44 percent of participants did not see a physician or visit the hospital after a syncopal event.1

A retrospective study of more than 70,000 patients in the Netherlands compared the evaluation of syncope in the primary care setting versus the emergency department. The event rate for syncope in general practice exceeded the rate in the emergency department by a factor of 13 (9.3 versus 0.7 per 1,000 patient-years).3 Patients presenting to the emergency department with syncope were older and had a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disorders. Patients younger than 40 years with no history of cardiac disease rarely had a life-threatening condition.

Patients with syncope create a difficult diagnostic dilemma. Physicians must determine the extent of evaluation, which diagnostic tests to order, whether hospital admission is needed, and the prognosis and risk of recurrent syncope. Approximately 20 to 50 percent of patients have unexplained syncope after intensive diagnostic evaluation.4,5 Standardized clinical evaluations have been developed to stratify risk and determine which patients benefit from hospitalization and diagnostic evaluation.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with syncope and evidence of heart failure or structural heart disease should be admitted to the hospital for monitoring and evaluation. | C | 13, 17, 19 |

| All patients presenting with syncope should have orthostatic vital signs and standard 12-lead electrocardiography. | C | 2, 5, 13, 17, 19 |

| Laboratory testing in the evaluation of syncope should be ordered as clinically indicated by the history and physical examination. | C | 4, 5, 13, 19 |

| Indications for electrophysiology include patients with coronary artery disease and syncope, coronary artery disease with an ejection fraction less than 35 percent, and possibly nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. | C | 17 |

| Patients at low risk of adverse events (i.e., those with symptoms consistent with vasovagal or orthostatic syncope, no history of heart disease, no family history of sudden cardiac death, normal electrocardiographic findings, unremarkable examination, and younger patients) may be safely followed without further intervention or treatment. | B | 13, 17, 19 |

Classification and Differential Diagnosis

Syncope is classified as neurally mediated (reflex), cardiac, orthostatic, or neurologic (Table 1). The prevalence of these classifications, based on five population-based studies with 1,002 unselected patients with syncope, is shown in Table 2.5 Neurally mediated syncope is the most common and is seen primarily in young adults. A reflex response causes vasodilation, bradycardia, and systemic hypotension leading to decreased cerebral blood flow. Neurally mediated syncope includes vasovagal syncope, situational syncope, and carotid sinus syndrome/hypersensitivity.

| Classification | Examples | Scenario | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | Arrhythmia (e.g., bradyarrhythmias, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, long QT syndrome), pacemaker dysfunction | Generally abrupt and unprovoked, palpitations may precede symptoms | Presence of heart disease, family history of sudden death, symptoms during or after exertion, sudden onset of palpitations, electrocardiographic abnormalities |

| Obstructive cardiomyopathy | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | Often asymptomatic; may cause shortness of breath, chest pain, arrhythmia, or syncope; hypertrophic cardiomyopathy may cause systolic murmur that intensifies from squatting to standing or during Valsalva maneuver | |

| Structural disease (cardiac) | Aortic stenosis | Symptoms dependent on severity; severe aortic stenosis can manifest with congestive heart failure, syncope, or angina usually with exertion | |

| Pulmonary stenosis | Rare as an isolated finding in adults, often in association with congenital defects; symptoms based on severity and range from asymptomatic to shortness of breath/dyspnea on exertion, congestive heart failure, and syncope | ||

| Acute myocardial infarction/ischemia | Exertional chest pain, nausea, diaphoresis and shortness of breath; rare cause of syncope | ||

| Structural disease (other) | Pulmonary embolus | Acute shortness of breath, chest pain, hypoxia, sinus tachycardia or right heart strain | |

| Acute aortic dissection | Severe sharp chest pain with or without radiation to the back, hypotension or shock, history of hypertension | ||

| Pulmonary hypertension | Often asymptomatic, may cause shortness of breath and fatigue | ||

| Neurally mediated (reflex) | Carotid sinus syndrome/hypersensitivity | Head rotation or pressure on the carotid sinus (e.g., shaving, tight collar) can reproduce symptoms; consider in patients with unexplained falls | Perform carotid sinus massage; ventricular pause more than three seconds or decrease in systolic blood pressure ≥ 50 mm Hg is diagnostic |

| Situational | Micturition, post-exercise, postprandial, gastrointestinal stimulation, cough, phobia of needle or blood | Absence of heart disease, history of similar syncope, prolonged standing, eating a meal or voiding, sudden startle or pain | |

| Vasovagal | Mediated by stress, fear, noxious stimuli, heat exposure | Premonitory symptoms (e.g., nausea, dizziness) or precipitating factors | |

| Neurologic/miscellaneous | Cerebrovascular | Induced by a steal syndrome | Arm exercise induces a syncopal event |

| Neurogenic | Preceding transient ischemic attack/cerebrovascular injury symptoms; severe basilar artery disease | Abnormal findings on neurologic examination, cardiovascular risk factors present, syncope from transient ischemic attack is rare | |

| Psychogenic | Depression, anxiety, panic disorder, somatization disorders | Psychiatric history, secondary gain, unremarkable examination and evaluation findings | |

| Orthostatic | Drug-induced | Alcohol, insulin or antidiabetic agents, antihypertensives, antianginals, antidepressants, antiparkinsonian agents | Initiation or change in dose of causative medication; assess for drug-drug interactions |

| Primary autonomic failure | Parkinson disease/parkinsonism, multiple system atrophy (i.e., Shy-Drager syndrome), multiple sclerosis, Wernicke encephalopathy | Occurs after standing up, presence of autonomic dysfunction, precipitated by standing after exercise | |

| Secondary autonomic failure | Diabetes mellitus, amyloidosis, uremia, spinal cord injury, chronic inflammatory polyneuropathy, connective tissue diseases | Occurs after standing up, presence of autonomic dysfunction, precipitated by standing after exercise | |

| Volume depletion | Vomiting, diarrhea, poor intake, acute blood loss (i.e., gastrointestinal bleeding) | Hypotension, tachycardia, history of volume/blood loss, dehydration on examination |

| Type of syncope | Mean prevalence of syncope (%)* | |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | ||

| Arrhythmia | 14 (4 to 38) | |

| Structural disease | 4 (1 to 8) | |

| Neurally mediated | ||

| Carotid sinus | 1 (0 to 4) | |

| Situational | 5 (1 to 8) | |

| Vasovagal | 18 (8 to 37) | |

| Neurologic | 10 (3 to 32) | |

| Orthostatic | 8 (4 to 10) | |

| Psychogenic | 2 (1 to 7) | |

| Unknown | 34 (13 to 41) | |

Cardiac syncope is the second most common type of syncope. It results from arrhythmias, mechanical abnormalities, or structural abnormalities, and is generally seen in older adults. Cardiac causes of syncope often are unprovoked and are more likely to present in the emergency department. Sudden death in young adults with syncope is often the result of arrhythmias. Orthostatic hypotension can be caused by autonomic dysfunction, medications, or volume depletion resulting in syncope. It is rare in patients younger than 40 years, and is commonly seen in older patients with comorbid conditions.1,6

Common nonsyncopal syndromes that do not involve impairment of consciousness include falls, cataplexy, drop attacks, pseudoseizures, psychogenic conditions (e.g., anxiety, hysterical fainting), and transient ischemic attacks (carotid in origin). Metabolic disorders (e.g., hypoglycemia, hypoxia, hyperventilation), seizures, acute intoxications, and vertebrobasilar insufficiency may present as syncope with partial or complete loss of consciousness.

Seizures often can be confused with syncope. In a study attempting to distinguish syncope from seizures, the features most suggestive of a seizure were tongue laceration, head turning, and witnessed abnormal posturing. Factors strongly predictive against seizure were presyncope spells before loss of consciousness, diaphoresis before a spell, and loss of consciousness with prolonged standing or sitting.7 Any suspected seizure disorder should be confirmed by electroencephalography.

Initial Risk Stratification

Patients with syncope have an increased risk of death from any cause (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.3; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1 to 1.5) and cardiovascular events (HR = 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0 to 1.6). When syncope is secondary to a cardiac etiology, the risk of death from any cause is more than twofold (HR = 2.0; 95% CI, 1.5 to 2.7). Neurally mediated and orthostatic syncope do not confer an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity or mortality.1

Several clinical decision rules have been developed to aid physicians in determining the short-term risk of death. A prospective cohort study applied the San Francisco Syncope Rule (SFSR) to 791 patients evaluated for syncope in the emergency department.8 Participants were followed to determine serious outcome within 30 days of the visit. Predictors of serious outcomes were systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, shortness of breath, history of congestive heart failure, abnormal electrocardiography (ECG), and hematocrit level less than 30 percent. Eighteen percent of patients who had one or more predictors on the SFSR had at least one serious outcome compared with 0.3 percent when the SFSR result was negative (no predictors). The SFSR was 98 percent sensitive and 56 percent specific for syncope, with a negative predictive value of 99.7 percent.8 However, two separate external validation studies of the SFSR have shown lower sensitivity rates (89 to 90 percent), thus challenging the reliability of the rule to safely discharge patients.9–11

The most recent clinical decision rule used to predict one-month serious outcome is the Risk Stratification of Syncope in the Emergency Department (ROSE), a single-center, prospective, observational study of 550 adults with syncope. Independent predictors of the ROSE rule form the mnemonic BRACES, which includes brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels of 300 pg per mL (300 ng per L) or greater; bradycardia of 50 beats per minute or less; rectal examination with positive fecal occult blood test; anemia (hemoglobin of 9 g per dL [90 g per L] or less); chest pain with syncope; ECG with Q waves; and oxygen saturation of 94 percent or less on room air. Patients are considered high-risk if any of the seven criteria are present. The rule has an 87 percent sensitivity and a 98 percent negative predictive value for one-month serious outcome in patients with syncope presenting to the emergency department.12

Risk stratification can aid in determining the need for hospitalization (Table 3).13,14 A major justification for admission is the physician's concern that a patient is at increased risk of significant dysrhythmia or sudden death. Observation in a monitored setting may be of value in patients with clinical or ECG features suggestive of cardiac syncope. However, there is a lack of evidence showing which patients benefit from short-term observation to prevent future adverse events. The diagnostic yield of ECG monitoring during short-stay admissions to detect dysrhythmias may be only as high as 16 percent.15 Despite this limitation, patients are high-risk and should be admitted if they have known structural heart or coronary artery disease (CAD), syncope in the supine position or during exertion, palpitations associated with syncope, family history of sudden cardiac death, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, or an abnormal ECG. Patients with significant comorbid conditions or severe injury from syncope also should be hospitalized. Low-risk patients can be evaluated safely in the outpatient setting.16

| High-risk (hospital admission recommended)* |

| Clinical history suggestive of arrhythmia syncope (e.g., syncope during exercise, palpitations at time of syncope) |

| Comorbidities (e.g., severe anemia, electrolyte abnormalities) |

| Electrocardiographic history suggestive of arrhythmia syncope (e.g., bifascicular block, sinus bradycardia < 40 beats per minute in absence of sinoatrial block or medications, preexcited QRS complex, abnormal QT interval, ST segment elevation leads V1 through V3 [Brugada syndrome], negative T wave in right precordial leads and epsilon wave [arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy]) |

| Family history of sudden death |

| Older age† |

| Severe structural heart or coronary artery disease |

| Low-risk (outpatient evaluation recommended)‡ |

| Age younger than 50 years† |

| No history of cardiovascular disease |

| Normal electrocardiographic findings |

| Symptoms consistent with neurally mediated or orthostatic syncope |

| Unremarkable cardiovascular examination |

History and Physical Examination

The history and physical examination are the most important tools in the initial evaluation of syncope. Details of the syncopal event must be investigated, including postural, exertional, or situational symptoms; palpitations or cardiac symptoms; use of medications; family history of sudden cardiac death; and personal history of cardiac disease (Table 4).2,5,6,13,17 A study evaluating 341 consecutive patients referred to a syncope unit showed that history and examination established the diagnosis in 14 percent of cases, which was more significant than results from ECG (10 percent), Holter monitor (5 percent), electrophysiology (5 percent), or echocardiography (1 percent).6 Physical examination should focus on vital signs (including orthostasis), as well as the cardiovascular (presence of murmur, arrhythmia), neurologic (muscle weakness/ paresthesia or cranial nerve abnormalities), vascular (bruits), and gastrointestinal (blood loss) systems.

| Features | Possible diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|

| Precipitating factors | ||

| Warm/crowded area, pain, emotional distress, fear | Neurally mediated (vasovagal), orthostatic | |

| Activities such as coughing, laughing, urination/defecation, eating | Neurally mediated (situational) | |

| Unexplained fall | Neurally mediated (carotid sinus) or cardiac (arrhythmia, structural heart disease) | |

| Head movement, tight collars, shaving | Neurally mediated (carotid sinus) | |

| During exertion | Cardiac (arrhythmia, structural heart disease) | |

| Shortly after exertion | Neurally mediated (vasovagal), cardiac (arrhythmia) | |

| Prolonged sitting/standing up | Orthostatic | |

| Addition or use of medication | ||

| Antiarrhythmics | Cardiac (arrhythmia, prolonged QT interval) | |

| Antihypertensives | Orthostatic, cardiac (prolonged QT interval) | |

| Macrolides, antiemetics, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants | Cardiac (prolonged QT interval) | |

| Hand or upper extremity exercise | Neurogenic (steal syndrome) | |

| Prodrome | ||

| Lightheadedness, dizziness, blurred vision, vertigo | Neurally mediated (vasovagal), orthostatic | |

| Nausea, diaphoretic, abdominal pain | Neurally mediated (vasovagal) | |

| Focal neurologic deficit | Neurogenic (cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack) | |

| Chest pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea | Cardiac (structural heart disease, pulmonary embolus, acute myocardial infarction) | |

| Auras | Seizure | |

| Fluttering or palpitations | Cardiac (arrhythmia) | |

| Slow pulse | Neurally mediated (vasovagal), cardiac (bradyarrhythmia) | |

| Tonic-clonic movement/posturing | Seizure | |

| None | Vasovagal or cardiac in older patients, cardiac in younger patients | |

| Position before syncope | ||

| Prolonged standing | Neurally mediated (vasovagal), orthostatic | |

| Sudden change in posture | Orthostatic | |

| Supine | Cardiac (arrhythmia, structural heart disease) | |

| Postsyncope | ||

| Nausea, vomiting, fatigue | Neurally mediated (vasovagal) | |

| Immediate complete recovery | Cardiac (arrhythmia), psychogenic | |

| Pallor, sweating | Likely syncope (any cause) versus seizure | |

| Focal neurologic deficit | Neurogenic (cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack) | |

| Myoclonic movement | Neurally mediated (vasovagal) | |

| Tonic-clonic movement/posturing | Seizure | |

| Eyes open during event | Seizure or syncope (any cause) | |

| Eyes closed during event | Pseudoseizure, psychogenic | |

| Prolonged confusion | Seizure | |

| Transient disorientation | Neurally mediated (vasovagal) | |

| Amnesia regarding loss of consciousness | Seizure or neurally mediated (vasovagal) in older patients | |

| Incontinence | Seizure, uncommon in syncope (vasovagal most likely) | |

| Tongue biting | Seizure | |

| Significant trauma | Syncope (any cause), unlikely seizure | |

| Chest pain, shortness of breath, dyspnea | Cardiac (structural heart disease, pulmonary embolus, acute myocardial infarction) | |

| Prolonged syncope | Seizure, neurogenic, metabolic, infectious | |

| Slow pulse | Cardiac (bradyarrhythmia) | |

| Preexisting disease | ||

| Heart disease | Cardiac | |

| Psychiatric illness | Psychogenic | |

| Diabetes mellitus, Parkinson disease, alcoholism, renal replacement therapy | Orthostatic | |

| Family history of sudden cardiac death | Cardiac (long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy, structural heart disease) | |

| Frequent and long history of syncopal events | Psychogenic, neurally mediated (vasovagal) | |

| Older age with dementia | Orthostatic, cardiac | |

Vasovagal syncope may be diagnosed if there is a common precipitating factor with associated prodromal symptoms. Patients who experience syncope with urination, defecation, cough, swallowing, or venipuncture have situational syncope. Documented or reproducible orthostatic hypotension in association with syncope is diagnostic for orthostatic syncope. Syncope related to ischemia is presumed when symptoms are present with ischemic ECG findings. Arrhythmia-related syncope is suspected in patients with severe bradycardia (less than 40 beats per minute), second- or third-degree blocks, ventricular tachycardia, or pacemaker malfunction. A neurologic etiology is suggested in patients with abnormal cognition, speech disturbance, or sensory-motor deficiencies. Young patients who have frequent syncopal events, multiple vague symptoms, and no injury history should be screened for psychiatric disorders.

Carotid sinus massage is useful for diagnosing carotid sinus hypersensitivity. The European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend carotid sinus massage in patients older than 40 years presenting with syncope of unknown etiology.13 In carotid sinus massage, the physician applies pressure over the carotid bifurcation, which produces bradycardia and a fall in blood pressure during continuous cardiovascular monitoring. Carotid sinus hypersensitivity is diagnostic when this maneuver produces a ventricular pause longer than three seconds or a decrease in systolic blood pressure of 50 mm Hg or more.13 Contraindications for carotid sinus massage include the presence of a bruit or previous history of cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack within the previous three months. Carotid sinus massage has a 39 percent false-positive rate in older patients with no history of syncope.18 If the history is not suggestive of carotid sinus hypersensitivity despite a positive carotid sinus massage, another diagnosis should be considered.

Diagnostic Testing

LABORATORY ASSESSMENT

Standardized testing (i.e., clinical evaluation, carotid sinus massage, ECG, and basic laboratory testing) has been shown to identify the etiology of syncope in 69 percent of patients (Table 513 ).4 All patients presenting with syncope should have standard 12-lead ECG and QT interval monitoring.2,5,13,17,19 However, the routine use of a broad panel of laboratory tests is not recommended; tests should be ordered as clinically indicated by the history and physical examination, because fewer than 2 to 3 percent of patients evaluated for syncope will have abnormal laboratory results.4,5 In a population-based study, laboratory testing was diagnostic in only five (0.8 percent) of 650 consecutive patients (diagnosed with gastrointestinal hemorrhage or hypoglycemia) presenting to the emergency department with syncope.4 A complete blood count is recommended for risk stratification in the SFSR and ROSE clinical decision rules to evaluate for anemia.

| Test | Indication | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Basic laboratory testing | As clinically indicated, including human chorionic gonadotropin in women of childbearing age | Laboratory evaluation rarely is helpful; complete blood count for anemia; brain natriuretic peptide testing may be beneficial for cardiac etiology |

| Carotid sinus massage | Syncope of unknown etiology in patients older than 40 years* | Diagnostic if ventricular pause is more than three seconds or if a decrease in systolic blood pressure > 50 mm Hg |

| Contraindicated in patients with bruits or a history of transient ischemic attack/cerebrovascular accident within the past three months | ||

| ECG | All patients with syncope | Can aid in diagnosing arrhythmia, ischemia, pulmonary embolus (increased pulmonary pressures or right ventricular enlargement), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Findings suggestive of arrhythmia include presence of bundle branch block, intraventricular conduction delay, sinus bradycardia (less than 50 beats per minute), prolonged QT interval, QRS preexcitation, Q waves | ||

| ECG monitoring | Recurrent syncope with unremarkable initial evaluation; clinical or ECG features suggestive of arrhythmic syncope; patients with unexplained falls* | Holter monitor for 24 to 48 hours, event recorders for 30 to 60 days, implantable recorders for up to 14 months |

| Consider testing in patients suspected of having epilepsy not responsive to therapy | ||

| Echocardiography | When history, examination, and ECG do not provide a diagnosis or if structural cardiac disease is suspected | Diagnostic in aortic stenosis, pericardial tamponade, obstructive cardiac tumors or thrombi, aortic dissection, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries |

| Electrophysiology | Patients with coronary artery disease after ischemic evaluation, nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, bundle branch block,* syncope preceded by palpitations, Brugada syndrome, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy, or high-risk occupations | Not recommended in patients without underlying heart disease |

| Consider in high-risk patients with recurrent unexplained syncope | ||

| Exercise testing | Hemodynamic and ECG abnormalities present with syncope during exercise, syncope reproduced with exercise, precipitate a Mobitz type II second- or third-degree block during exercise* | Inadequate rise of blood pressure in younger patients is suggestive of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy or left main disease; similar findings in older persons may suggest autonomic dysfunction |

| Neurologic testing† | Suspicious for seizures, cerebrovascular event, neurodegenerative disorders, increased intracranial pressure | Seizure can be confirmed with electroencephalography |

| Cranial imaging studies as clinically indicated | ||

| Orthostatic blood pressure | Evaluate neurally mediated syncope from orthostatic hypotension* | Diagnostic if decrease in systolic blood pressure ≥ 20 mm Hg; if systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg; or if decrease in diastolic blood pressure ≥ 10 mm Hg with symptoms |

| Consider diagnostic even when patient is asymptomatic | ||

| Psychiatric evaluation | When syncope is suspected to be psychogenic* | Consider with concurrent electroencephalography and video monitoring |

| Tilt-table testing | Evaluate neurally mediated syncope, distinguish between neurally mediated and orthostatic hypotension,* recurrent unexplained falls, differentiate syncope with jerking movements from seizure, frequent syncopal episodes and psychiatric disease | Used when initial evaluation findings are negative, normal cardiac structure, and no evidence of ischemia |

| Contraindicated in patients with ischemic heart disease, uncontrolled hypertension, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction, or aortic stenosis |

In a prospective cohort study (237 participants) evaluating syncope, 44 percent of patients had elevated d-dimer levels. However, it did not predict one-month serious outcomes or death, so the use of d-dimer levels in syncope evaluation is not recommended.20 BNP has been studied as a marker for distinguishing cardiac from noncardiac causes of syncope. A retrospective study demonstrated 82 percent sensitivity and 92 percent specificity for identifying cardiac causes of syncope when the BNP level is elevated (positive likelihood ratio = 10; negative likelihood ratio = 0.2).21 The ROSE study found that an elevated BNP level (300 pg per mL or higher) was an important independent predictor of serious cardiovascular outcomes; abnormal values were seen in patients with eight of 22 events and in eight of nine deaths.21 Thus, a reasonable initial laboratory evaluation would include a serum glucose test, a pregnancy test for women of childbearing age, a complete blood count, and BNP measurement if the ROSE tool is used for risk stratification.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

Echocardiography is used to measure ejection fraction and to identify the presence of hypertrophy and underlying cardiac lesions. Its role in the initial evaluation of syncope remains less clear, especially in patients with an unremarkable examination, unremarkable ECG, and no cardiac history. In a prospective study, a probable cause was found in 495 of the 650 consecutive patients with syncope who underwent a comprehensive evaluation.22 The remaining 155 patients were considered to have unexplained syncope. Of these 155 patients, echocardiography was unremarkable in all 67 (43 percent) with a normal ECG and negative cardiac history. Of those with abnormal ECG or positive cardiac history, 27 percent had systolic dysfunction. The remainder of patients had minor echocardiographic findings that were not relevant. These results suggest that echocardiography is most useful in patients with unexplained syncope and a positive cardiac history or abnormal ECG.22

GRADED EXERCISE TESTING

Graded exercise testing is useful to evaluate patients at risk of cardiovascular disease, those with unexplained syncope, and those with syncope during or shortly after exercise. In addition to the evaluation of ischemia, exercise testing can also provide blood pressure and pulse response to exercise. In patients younger than 40 years, an inadequate blood pressure response to exercise suggests severe CAD or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.23 A similar response in older patients suggests CAD or autonomic failure. Observance of ventricular arrhythmia during exercise requires immediate cardiology consultation.

ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHIC MONITORING

Electrocardiographic monitoring is indicated when there is a high pretest probability of identifying an arrhythmia associated with syncope. Patients with an unremarkable cardiovascular evaluation (echocardiography and ischemic evaluation) but who are at high risk of syncope recurrence should undergo electrocardiographic monitoring. Ambulatory monitors have evolved from the Holter monitor to implantable loop recorders designed to monitor for more than 12 months. The overall diagnostic yield of ambulatory monitoring is low, but is increased with longer surveillance. Previous studies have demonstrated a 22 percent overall yield for symptom-rhythm correlation with a Holter monitor compared with 50 to 85 percent for loop recorders.24 When patients had 14-month symptom-free surveillance with loop recorders, 92 percent of the patients remained free of syncope in the following two years.25

TILT-TABLE TESTING

Tilt-table testing is useful to confirm the diagnosis of suspected neurally mediated syncope in the absence of structural heart disease or ischemia. Patients are supine in the pre-tilt phase and then placed at 60 to 70 degrees for 20 to 45 minutes. If no event is reproduced and vital signs remain normal, then testing is repeated with pharmacologic provocation. The most common protocol is infusion of isoproterenol (Isuprel) or sublingual nitroglycerin. The test is considered positive if the patient has a symptomatic decrease in systolic blood pressure or bradycardia. Overall sensitivity ranges from 26 to 80 percent, and specificity is 90 percent.17

ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY

The American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation (AHA/ACCF) indications for electrophysiology include CAD and syncope, CAD with an ejection fraction less than 35 percent, and possibly nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy.17 The European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend electrophysiology in patients with structural heart disease.13 In a 2009 study, patients with unexplained syncope underwent noninvasive electrocardiographic and electrophysiologic evaluation.26 Noninvasive testing (ECG and 24-hour Holter monitor) was used to predict electrophysiologic outcomes. Among patients with an abnormal ECG, 82 percent had an abnormal electrophysiologic result, compared with 9 percent when patients had a normal ECG and normal 24-hour Holter monitor.26

Approach to the Patient

The AHA/ACCF Scientific Statement on the Evaluation of Syncope,17 the European Society of Cardiology Task Force on Syncope,13 and the American College of Emergency Physicians19 clinical policy offer guidelines for the evaluation of patients with syncope. The AHA/ACCF outlines an algorithmic approach to syncope (Figure 1).17 If the initial evaluation (history, physical examination, and ECG) is nondiagnostic, echocardiography and ischemic evaluation are recommended. Patients with syncope unexplained by this evaluation may require additional tests, such as electrocardiographic monitoring, electrophysiologic studies, tilt-table testing, neurologic assessment, and psychiatric assessment based on suspected etiology and frequency of syncope. Younger patients with an initial normal evaluation, symptoms consistent with vasovagal or orthostatic syncope, no history of heart disease, and no family history of sudden death are at low risk of an adverse event and may be safely followed without further intervention or treatment.13,17,19

Specific Situations

CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE

Syncope in patients with CAD requires evaluation for arrhythmia and ischemia. The evaluation includes exercise stress testing, myocardial perfusion imaging, or cardiac catheterization, depending on the patient's level of risk and specific findings. Ventricular arrhythmia remains a risk despite revascularization, and an arrhythmia evaluation must be completed. Electrophysiology is recommended when the left ventricular ejection fraction is less than 35 percent. An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) improves overall survival in patients with an ejection fraction less than 35 percent.27

NONISCHEMIC DILATED CARDIOMYOPATHY

Electrophysiology is usually performed in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy to rule out arrhythmia, because recurrence of syncope is usually secondary to ventricular tachyarrhythmias. An ICD may be offered to patients with a negative electrophysiologic study result. Patients randomized to prophylactic ICD and standard medical therapy versus standard medical therapy alone had fewer deaths from arrhythmias (1.3 versus 7.4 percent; P = .006; number needed to treat = 17) and lower overall mortality at two years (7 versus 14 percent).28

STRUCTURAL HEART DISEASE

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy are genetic syndromes associated with increased sudden death from arrhythmia. Syncope is an ominous sign for patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy and confers a fivefold risk of sudden cardiac death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy when associated with exercise. For both of these conditions, ICD may be appropriate to decrease the risk of sudden death.17

INHERITED CARDIAC ION CHANNEL ABNORMALITIES

The two most common inherited cardiac ion channel abnormalities are Brugada syndrome and long QT syndrome. Both conditions are caused by a genetic mutation not typically associated with structural heart disease. For patients with long QT syndrome, the risk of syncope and sudden death is associated with the degree of QT prolongation. Syncope results from ventricular tachycardia or torsade de pointes, which may lead to sudden cardiac death. Treatment options are chronic beta-blocker therapy or an ICD. Medications known to prolong the QT interval should be avoided (a list of medications is available at http://www.azcert.org/medical-pros/drug-lists/drug-lists.cfm).

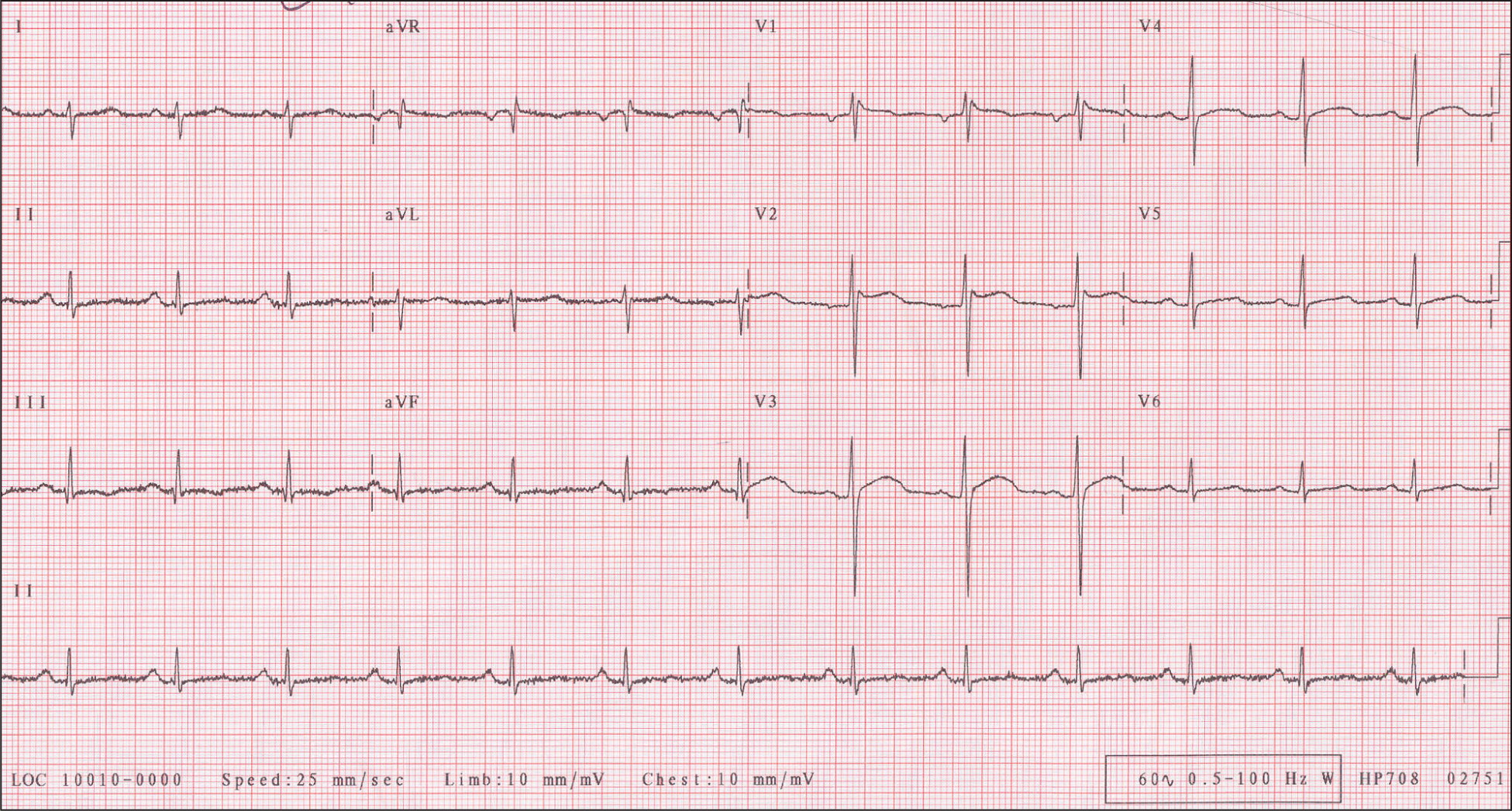

Brugada syndrome is a disorder of the sodium channel. ECG findings are ST-segment elevation in V1 through V3 and/or right bundle branch block (Figure 2).29 Symptomatic Brugada syndrome has a high rate of malignant arrhythmias and a two-year mortality rate of 30 percent.30 An ICD is recommended to protect against fatal arrhythmias.

OLDER PATIENTS

The incidence of syncope increases sharply after 70 years of age and poses special consideration in light of multiple comorbid conditions, age-related changes, atypical presentation, and concomitant medication use. The most common causes of syncope in this population are orthostatic hypotension (often occurring in the morning after taking medications), carotid sinus hypersensitivity, and cardiac causes.

Syncope in older persons generally has more than one etiology, making the diagnosis more difficult. Pertinent information includes medication history in relationship to syncope, level of cognitive impairment, and physical frailty. The observation of a gait disturbance or balance instability places patients at increased risk of falls, irrespective of a syncopal event. The approach to syncope remains the same in this population but with a lower threshold for hospitalization.

Data Sources: The following sources were searched for this article: National Guideline Clearinghouse, Essential Evidence Plus, European Society of Cardiology Clinical Practice Guidelines, American College of Cardiology: Statements and Clinical Practice Guidelines, American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee, and UpToDate. Key terms included the following: syncope (epidemiology, etiology, history, mortality), clinical guidelines, echocardiography (utilization, standards), vasovagal, tilt-table test, orthostatic syncope, Brugada syndrome, ICD, electrophysiologic monitoring, carotid sinus massage, mortality, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, vasovagal (neurocardiogenic), orthostatic hypotension, carotid sinus hypersensitivity, and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Search date: October 19, 2010.