A more recent article on sarcoidosis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(10):840-850

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown etiology characterized by the presence of noncaseating granulomas in any organ, most commonly the lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes. A diagnosis of sarcoidosis should be suspected in any young or middle-aged adult presenting with unexplained cough, shortness of breath, or constitutional symptoms, especially among blacks or Scandinavians. Diagnosis relies on three criteria: (1) a compatible clinical and radiologic presentation, (2) pathologic evidence of noncaseating granulomas, and (3) exclusion of other diseases with similar findings, such as infections or malignancy. An early and accurate diagnosis of sarcoidosis remains challenging, because initial presentations may vary, many patients are asymptomatic, and there is no single reliable diagnostic test. Prognosis is variable and depends on epidemiologic factors, mode of onset, initial clinical course, and specific organ involvement. The optimal treatment for sarcoidosis remains unclear, but corticosteroid therapy has been the mainstay of therapy for those with significantly symptomatic or progressive pulmonary disease or serious extrapulmonary disease. Refractory or complex cases may require immunosuppressive therapy. Despite aggressive treatment, some patients may develop life-threatening pulmonary, cardiac, or neurologic complications from severe, progressive disease. End-stage disease may ultimately require lung or heart transplantation for eligible patients.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology that most often affects the lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes but can involve any organ of the body (Table 1).1,2 The paucity of randomized controlled trials has led to limited evidence-based data for clinicians caring for patients with sarcoidosis. This article reviews the epidemiology, etiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and current evidence on the treatment of pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Consider sarcoidosis in patients with unexplained cough, shortness of breath, or constitutional symptoms, especially in groups with a higher prevalence, such as blacks or Scandinavians. | C | 1 |

| Diagnosis of sarcoidosis relies on three criteria: (1) a compatible clinical and radiologic presentation, (2) pathologic evidence of noncaseating granulomas, and (3) exclusion of other diseases with similar findings, such as infections or malignancy. | C | 1 |

| Cardiac or neurologic sarcoidosis can result in irreversible or life-threatening disease and often requires aggressive treatment with high-dose corticosteroids. | C | 39–42 |

| Treatment is not indicated for patients with asymptomatic stage I or II sarcoidosis because spontaneous resolution is common. | C | 1 |

| Treatment with corticosteroids should be considered for patients with significant symptomatic or progressive stage II or III pulmonary disease or serious extrapulmonary disease. | B | 1, 47, 48 |

| Patients with refractory or complex cases of sarcoidosis may require additional immunosuppressive therapy. | C | 1, 51, 52 |

| Organ system | Prevalence (% of patients) | Clinical manifestations | Diagnostic workup |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediastinal lymph nodes | 95 to 98 | Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy | Chest radiography, chest CT, endoscopic ultrasonography with needle aspiration (endobronchial or esophageal), gallium scan, 18F-FDG PET (in select patients) |

| Lungs | > 90 | Cough, dyspnea | Chest radiography, chest CT (may be necessary) |

| Hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy | Chest radiography, chest CT, endoscopic ultrasonography with needle aspiration (endobronchial or esophageal), gallium scan, 18F-FDG PET (in select patients) | ||

| Pulmonary hypertension | Brain natriuretic peptide, six-minute walk test, echocardiography, right heart catheterization | ||

| Interstitial lung disease and pulmonary fibrosis | Chest radiography, chest CT, bronchoscopy, surgical lung biopsy (if needed) | ||

| Liver | 50 to 80 | Mostly asymptomatic, mild elevation in liver function tests | Liver biopsy if significant laboratory abnormalities |

| Spleen | 40 to 80 | Splenomegaly, rarely pain or cytopenias | Abdominal ultrasonography and abdominal CT |

| Eyes | 20 to 50 | Uveitis, retinal vascular changes, conjunctival nodules, lacrimal gland enlargement | Ophthalmologic evaluation, lacrimal gland biopsy (if necessary), gallium scan (in select patients) |

| Musculoskeletal | 25 to 39 | Proximal muscle weakness, myalgias, intramuscular nodules | Creatine kinase, MRI, 18F-FDG PET, possible muscle biopsy |

| Peripheral lymphadenopathy | 30 | Peripheral lymph nodes, most commonly cervical and supraclavicular nodes | Biopsy of most accessible and safest site, if needed to clarify diagnosis |

| Hematologic | 4 to 40 | Anemia, leukopenia | Complete blood count with differential, bone marrow biopsy in select patients |

| Skin | 25 | Papules, nodules, plaques, erythema nodosum, lupus pernio | Skin biopsy as needed, except for erythema nodosum and lupus pernio, which can usually be diagnosed clinically |

| Nervous system | 10 | Cranial nerve palsies | Brain MRI |

| Optic neuritis | Ophthalmologic evaluation | ||

| Hypopituitarism | Hormonal studies | ||

| Cognitive dysfunction | Brain MRI, cerebrospinal fluid studies | ||

| Small fiber neuropathy | Electromyography, nerve conduction studies | ||

| Heart | 5 | Conduction abnormalities, arrhythmias (including ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation), congestive heart failure, sudden death | Electrocardiography, echocardiography, Holter monitoring (depending on symptoms), cardiac MRI, 18F-FDG PET, thallium scan (in select patients) |

| Hypercalcemia | 2 to 10 | Nephrocalcinosis, renal stones, and renal failure | Biopsies, renal ultrasonography and CT urography |

| Parotid glands | < 6 | Isolated or associated with Heerfordt syndrome (uveoparotid fever) | Biopsy, gallium scan (in select patients) |

Epidemiology

Although sarcoidosis may affect anyone, it is most common in certain age groups, races, geographic regions, and families. More than 80% of cases occur in adults between 20 and 50 years of age.1 There is a second peak incidence between 50 and 65 years of age, especially among women in Scandinavia and Japan.3 Children are rarely affected.4 The lifetime risk of sarcoidosis in the United States is greater in blacks (2.4%) than whites (0.85%).5 Sarcoidosis is also more common in Swedes, Danes, and African-Caribbeans.1 Approximately 4% to 10% of patients have a first-degree relative with sarcoidosis.6

Pathogenesis and Etiology

Sarcoidosis is the result of noncaseating granuloma formation due to ongoing inflammation that causes the accumulation of activated T cells and macrophages, which then secrete cytokines and tumor necrosis factor-α.1 The precise cause of sarcoidosis is unknown. However, most studies suggest that it is the result of an exaggerated immune response in a genetically susceptible individual to an undefined antigen, such as certain environmental factors,7–9 microbes (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis,10–12 Propionibacterium acnes13), or partially degraded antigens. According to family-based and case-control association studies, there is strong evidence of a genetic predisposition to develop sarcoidosis.6,14

Natural History and Prognosis

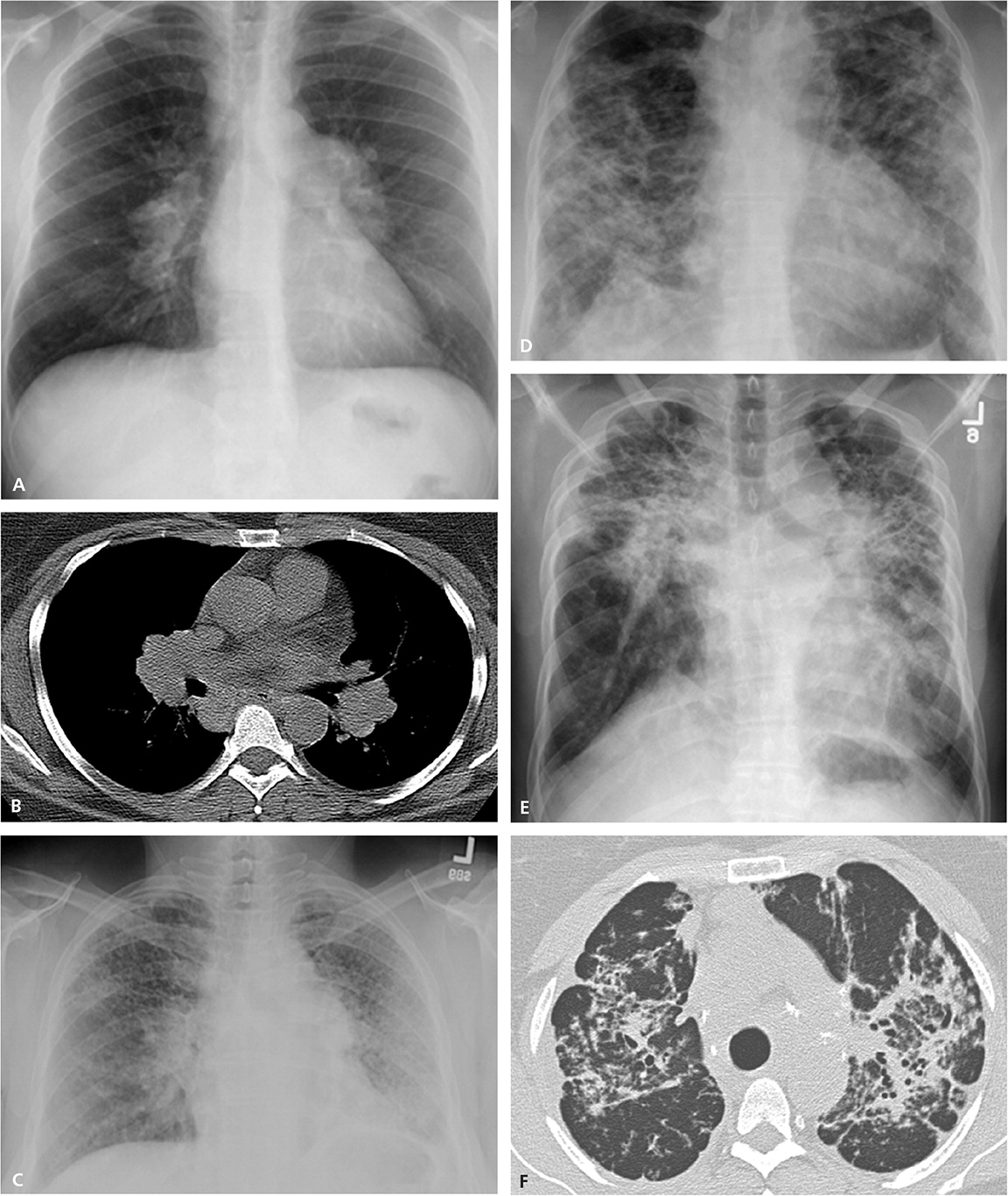

Although spontaneous remission may occur in nearly two-thirds of patients, between 10% and 30% of patients with sarcoidosis experience a chronic or progressive course.1 Early in the course of the disease, the prognosis for remission is more favorable, with spontaneous remission observed in 50% to 90% within the first two years of diagnosis, depending on disease stage.1 Patients who present with Löfgren syndrome have an excellent prognosis, with spontaneous remission in up to 80% of patients, usually within several months.1,15 Blacks are more likely to have a more symptomatic, severe, and chronic disease than whites.1,16 Radiologic stage by chest radiography at presentation is inversely correlated with the likelihood of spontaneous resolution (Table 21,2; Figure 1). Clinical staging systems predicting the risk of mortality have been proposed, but require further prospective validation in broader cohorts of patients.17

| Stage | Chest radiography results | Rates of spontaneous resolution | Suggested follow-up timeline* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Normal | — | — |

| I | Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy | 55% to 90% | Initially every six months, then annually if stable |

| II | Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates | 40% to 70% | Every three to six months indefinitely for stages II, III, and IV |

| III | Pulmonary infiltrates without bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy | 10% to 20% | |

| IV | Pulmonary fibrosis | 0% to 5% |

Overall lifetime sarcoidosis-related mortality is less than 5%.1 In the United States, mortality is usually associated with progressive respiratory or heart failure,1,18 especially in blacks and women, whereas in Sweden and Japan, the leading cause of death is predominantly myocardial involvement.19

Diagnosis

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Sarcoidosis should be considered in young or middle-aged adults presenting with unexplained cough, shortness of breath, or constitutional symptoms, especially in high-prevalence groups such as blacks or Scandinavians. A considerable percentage of patients are asymptomatic at presentation, and the diagnosis is based on incidental bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy on chest radiography. Common presenting symptoms are outlined in Table 1.1,2 Constitutional symptoms, such as fever, unintentional weight loss, and fatigue, occur in about one-third of patients.1 Up to 50% of patients present with respiratory symptoms, such as shortness of breath, dry cough, and chest pain.1 The acute onset of erythema nodosum associated with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy, fevers, polyarthritis, and, commonly, uveitis is known as Löfgren syndrome. Another classic sarcoidosis syndrome is Heerfordt syndrome, or uveoparotid fever. It is characterized by uveitis, parotitis, fever, and, occasionally, facial nerve palsy.20 Other presenting findings depend on the extent of specific organ involvement.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND INITIAL EVALUATION

The differential diagnosis for sarcoidosis is broad because of the nonspecific symptoms and diverse clinical presentations. Many other diseases present with similar clinical, radiologic, and pathologic findings (Table 3).1 Infections (e.g., tuberculosis, histoplasmosis) and malignancy (e.g., lymphoma) should be ruled out if suspected. The initial evaluation starts with a history and physical examination, specifically focusing on risk factors for infectious, occupational, and environmental exposures. Laboratory studies should include a peripheral white blood cell count, serum chemistries (including calcium and creatinine levels, and liver function tests), urinalysis, and human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis tests.1 Because reduced skin reactivity is common in patients with sarcoidosis,21 an interferon gamma release assay may be more sensitive than tuberculin skin testing for identifying latent tuberculosis infection.22,23 Additional recommended testing should include baseline chest radiography, pulmonary function testing, and electrocardiography.1 Further testing should be based on specific organ involvement.

| Category | Specific disease |

|---|---|

| Exposures/toxins | Drug-induced hypersensitivity (e.g., adalimumab [Humira], etanercept [Enbrel], infliximab [Remicade], methotrexate) |

| Foreign body granulomatosis (aspiration or intravenous injection of foreign materials) | |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis | |

| Pneumoconioses (aluminum, beryllium, cobalt, talc, titanium, zirconium) | |

| Immunodeficiency | Chronic granulomatous disease |

| Common variable immunodeficiency | |

| Infections | Bacterial (brucellosis, nontuberculous mycobacteria, tuberculosis) |

| Fungal (aspergillosis, blastomycosis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly known as Pneumocystis carinii) | |

| Parasitic (echinococcosis, leishmaniasis, schistosomiasis, toxoplasmosis) | |

| Viral (human immunodeficiency virus) | |

| Inflammations | Bronchocentric granulomatosis (usually associated with asthma and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis) |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis (pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis) | |

| Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis | |

| Malignancy | Lymphoma |

| Lymphomatoid granulomatosis | |

| Sarcoid-like granuloma reactions (primary tumors, regional lymph nodes) | |

| Vasculitis | Churg-Strauss syndrome |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) |

CONFIRMATION OF THE DIAGNOSIS

According to an international consensus statement, there are three criteria for diagnosing sarcoidosis: (1) a compatible clinical and radiologic presentation, (2) pathologic evidence of noncaseating granulomas, and (3) exclusion of other diseases with similar findings (Figure 2).1 Certain sarcoidosis-specific syndromes, such as Löfgren and Heerfordt syndromes, can be diagnosed based on clinical presentation alone, avoiding the need for tissue biopsy.24 An asymptomatic patient with stage I sarcoidosis (i.e., bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy on chest radiography) without suspected infection or malignancy does not require invasive tissue biopsy because the results would not affect the recommended management approach (i.e., monitoring). If there would be an indication for treatment with a confirmed diagnosis (eTable A), pathologic evidence of noncaseating granulomas should be obtained from the most accessible and safest biopsy site. In addition to chest radiography, various imaging studies, such as computed tomography of the chest and 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET), are useful to support the diagnosis (Table 4).1,25,26 Reliable biomarkers for diagnosis do not currently exist for routine clinical practice, although some show promise.27,28 The serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level may be elevated in up to 75% of untreated patients.29 However, the ACE level lacks sufficient specificity,29 has large interindividual variability,30 and fails to consistently correlate with disease severity,31,32 which limits its clinical utility.

| Topical therapy |

| Skin lesions |

| Anterior uveitis |

| Cough or airway obstruction |

| Nasal polyps |

| Systemic therapy |

| Pulmonary compromise with symptomatic stage II to III disease, persistent infiltrates, decline in lung function |

| Cardiac disease |

| Neurosarcoidosis |

| Ocular disease not responding to topical therapy |

| Symptomatic hypercalcemia |

| Lupus pernio |

| Study | Findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Chest computed tomography | Useful particularly for the differential diagnosis of diffuse interstitial changes in lung parenchyma and pulmonary fibrosis | |

| Chest radiography | Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy and interstitial changes, necessary for staging | |

| 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography | Useful for finding areas to biopsy | |

| May aid in the diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis | ||

| May correlate with active inflammation and disease activity | ||

| Gallium scan | Lambda sign: increased uptake in the bilateral hilar and right paratracheal lymph nodes | |

| Panda sign: increased uptake in the parotid and lacrimal glands | ||

| Combined lambda and panda signs may be specific for sarcoidosis | ||

| Magnetic resonance imaging | Central nervous system: useful for identification of lesions | |

| Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging: | ||

| Findings include focal intramyocardial zones of increased signal intensity due to edema and inflammation | ||

| Delayed gadolinium enhancement is a predictor of ventricular arrhythmias and poor outcomes | ||

| Thallium scan | In cardiac sarcoidosis: | |

| Nonspecific areas of decreased myocardial uptake, not delimited by coronary artery distribution | ||

| Improvement or reverse distribution following dipyridamole (Persantine) administration allows differentiation from coronary artery disease | ||

Because the lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes are commonly affected, flexible bronchoscopy with biopsies have high diagnostic yields and low risk of complications. These include transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA), endobronchial biopsy, transbronchial lung biopsy, and, more recently, endosonography with nodal aspiration, either endobronchial ultrasound-guided TBNA or esophageal ultrasonography with fine-needle aspiration.33–35 Bronchoalveolar lavage with cell count may support a diagnosis of sarcoidosis if there is lymphocytosis of at least 15% and a CD4:CD8 T-lymphocyte ratio greater than 3.5.36 If less invasive tests are inconclusive, surgical biopsy of the mediastinum through mediastinoscopy of the lung via thoracoscopy or thoracotomy may be necessary. However, these procedures are associated with increased morbidity.37

Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis

Although the skin and eyes are the most common extrapulmonary organs to cause clinical manifestations, the heart and nervous system are the most serious.1,38 Monitoring extrapulmonary organs is essential because early recognition and treatment may prevent irreversible or life-threatening disease.1 Cardiac or neurologic sarcoidosis can result in irreversible or life-threatening disease and often requires aggressive treatment with high-dose corticosteroids.39–42

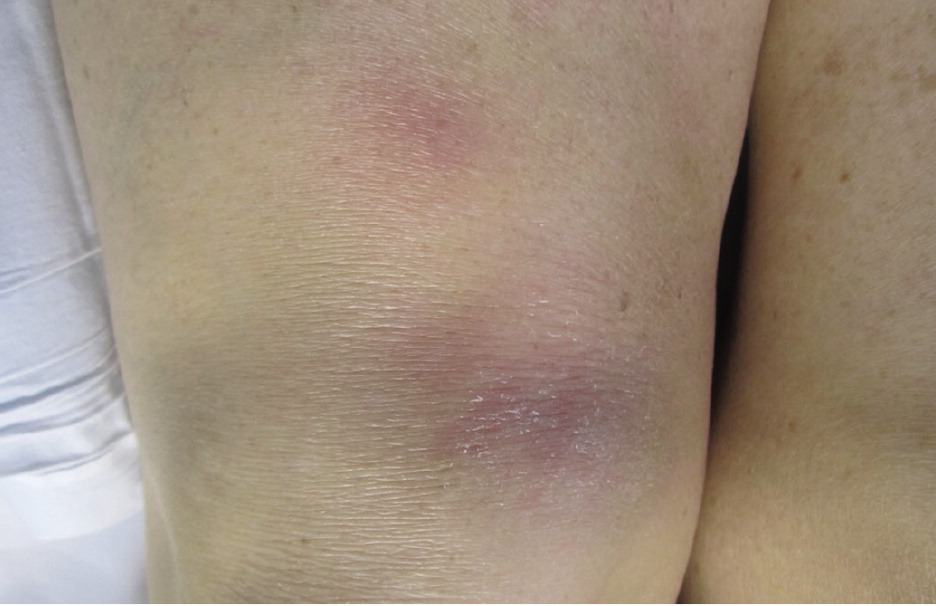

Cutaneous involvement occurs in about 25% of patients and is often an early finding; although usually asymptomatic, pruritus and pain have been reported.1 Skin lesions include macules, papules, plaques, ulcers, pustules, erythroderma, or hypopigmented lesions. Most lesions can be treated with topical agents, except in diffuse or unresponsive disease. The two most clinically important skin lesions are erythema nodosum (eFigure A), a nonspecific, nongranulomatous panniculitis that usually occurs in acute sarcoidosis, and lupus pernio (eFigure B), disfiguring red-to-purple plaques and nodules affecting the nose and cheeks that represent chronic sarcoidosis and require systemic treatment.

Because asymptomatic inflammation of the eye can result in permanent impairment, patients require yearly examinations and additional monitoring when the disease flares. Ocular involvement occurs in 20% to 50% of patients and is the presenting symptom in 5%.1 The most common manifestations are anterior uveitis (red, painful eye with photophobia or blurred vision) and keratoconjunctivitis (dry eye).43 These disorders can be treated with topical corticosteroids. Severe anterior or posterior uveitis requires systemic therapy. The most serious ocular complication is optic neuritis, which can result in rapid, irreversible loss of vision.

Although cardiac sarcoidosis is noted in 25% to 70% of autopsies, symptomatic cardiac involvement occurs in only about 5% of patients.39 Granulomas often infiltrate the conducting system, leading to arrhythmias and heart block, but cardiac involvement can also lead to dilated cardiomyopathy.40,41 Progressive heart failure and sudden death are the most serious complications of cardiac sarcoidosis. It is essential to evaluate palpitations and syncope or near syncope, and perform baseline electrocardiography. Any suggestion of cardiac involvement requires echocardiography and prompt referral to a cardiologist. Further cardiac imaging with magnetic resonance imaging or 18F-FDG PET should be considered if a diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis remains uncertain.44 Although cardiac sarcoidosis often responds to corticosteroids and immunosuppressant therapy, heart transplantation has been required in patients with end-stage cardiomyopathy.

Neurologic involvement occurs in about 10% of patients with sarcoidosis.42,45 Cranial neuropathy, particularly palsy of the seventh cranial nerve, is the most common neurologic complication. Sarcoidosis can result in mass-like lesions with focal symptoms or seizures, as well as acute or chronic meningitis and peripheral neuropathies. There is a predilection for the involvement of the pituitary gland and the hypothalamus, resulting in adrenal or pituitary failure, diabetes insipidus, and hypogonadism.

Calcium metabolism may also be dysregulated, resulting in hypercalciuria, hypercalcemia, and nephrolithiasis with possible renal insufficiency.1 Granulomatous inflammation activates vitamin D and leads to increased absorption of calcium from the gastrointestinal tract. Based on expert opinion and pathophysiologic reasoning, patients with active sarcoidosis are advised to reduce dietary calcium and calcium supplement intake, avoid sunlight, and drink adequate amounts of fluids.46

Treatment of Pulmonary Sarcoidosis

Treatment is not indicated for patients with asymptomatic stage I or II sarcoidosis because spontaneous resolution is common.1 Treatment with corticosteroids should be considered for patients with significant symptomatic or progressive stage II or III pulmonary disease or serious extrapulmonary disease. A meta-analysis identified 13 studies with 1,066 patients treated with systemic corticosteroids for six to 24 months. The authors found improvements in chest radiography findings, and limited data showed improvements in a global score incorporating symptoms and lung function in patients with stage II or III disease.47 However, there is no evidence that oral corticosteroids improve patient-oriented outcomes, such as mortality, or that they have any effect on long-term symptoms, lung function, radiologic findings, or disease progression. Nevertheless, corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment based on expert opinion and usual practice for patients with significant symptomatic or progressive stage II or III disease, or serious extrapulmonary disease.1,47,48

In addition, there are no validated protocols or algorithms for oral corticosteroid therapy. An international consensus statement recommended prednisone (or its equivalent) at a starting dosage of 20 to 40 mg per day for four to six weeks.1 If the patient's condition is stable or improved, the dosage should be tapered slowly to approximately 5 to 10 mg per day. If there is no clinical response after three months of steroid therapy, a response to longer courses is unlikely. Treatment should be continued for a minimum of 12 months before tapering off. Every-other-day dosing may be effective in some patients, but not all. There are limited data about the effectiveness of inhaled corticosteroids for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Some studies have found an improvement with endobronchial symptoms, such as cough, whereas others have not found a significant benefit.1,49,50

Patients should be monitored for clinical response and disease progression by symptoms, pulmonary function, and chest radiography after one to three months of treatment and every three to six months thereafter.1 There are no consistently reliable biomarkers (including serum ACE level) to aid in determining treatment response.1 Corticosteroid-related adverse effects (e.g., excessive weight gain, osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, gastritis, myopathy, opportunistic infections) should be assessed. Relapses after treatment are not uncommon and most often occur two to six months after corticosteroid withdrawal, but rarely after three years without symptoms.1

Second- and third-line therapies for pulmonary sarcoidosis,51,52 including methotrexate,51–55 azathioprine (Imuran),55,56 leflunomide (Arava),57 biologic agents,58–60 and corticotropin (H.P. Acthar) gel61 are reserved for patients with corticosteroid-refractory disease, intolerable adverse effects, or toxicity from corticosteroids, as well as patients who choose not to take corticosteroids. Corticosteroid refractory disease is defined as disease progression despite moderate dosages of prednisone (e.g., 10 to 15 mg per day) or frequent relapses. Second-line therapies are most often used in combination with prednisone, although data to guide the initiation, dosage, and duration of therapy are limited51,52 (eTable B). A Cochrane review of immunosuppressives and cytotoxic therapy for pulmonary sarcoidosis was unable to recommend the use of any of these agents.51 Among a group of sarcoidosis experts, methotrexate was the preferred second-line drug.54

| Medication | Dosage | Indication by organs involved | Significant adverse effects | Monitoring | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prednisone | 20 to 40 mg per day initially; 5 to 10 mg per day for long-term therapy | Pulmonary, cardiac, neurologic, ocular, cutaneous,† renal‡ | Weight gain, diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, hypertension, infections | Weight, glucose level, bone density, blood pressure | $10 for 20 mg per day |

| $15 for 40 mg per day | |||||

| Methotrexate | 10 to 15 mg per week | Pulmonary, cardiac, neurologic, ocular, cutaneous† | Nausea, leukopenia, liver/pulmonary toxicity, infections | Complete blood count, renal/liver indices every 1 to 3 months | $25 for 10 mg per week |

| $30 for 15 mg per week | |||||

| Azathioprine (Imuran) | 50 to 200 mg per day | Pulmonary, renal,‡ neurologic | Nausea, leukopenia, liver toxicity, infections | Consider thiopurine methyltransferase level and phenotype before initiation; complete blood count and liver function tests every 1 to 3 months | $30 ($200) for 50 mg per day |

| $100 ($900) for 200 mg per day | |||||

| Leflunomide (Arava) | 10 to 20 mg per day | Pulmonary, ocular, cutaneous | Nausea, diarrhea, liver toxicity, rash, peripheral neuropathy | Liver function tests every 1 to 3 months | $100 ($1,200) for 10 mg per day |

| $100 ($1,200) for 20 mg per day | |||||

| Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) | 200 to 400 mg per day | Cutaneous,† pulmonary, cardiac, neurologic, renal‡ | Retinopathy, rash, neuromyopathy | Eye examination every 6 to 12 months | $30 ($200) for 200 mg per day |

| $60 ($400) for 400 mg per day | |||||

| Infliximab (Remicade) | 5 mg per kg intravenously at weeks 0, 2, and 6, then monthly thereafter | Pulmonary, neurologic, cutaneous,† renal‡ | Infections (especially reactivation of TB), allergic reactions, antibody formation | TB assessment at initiation; close monitoring during infusions | NA ($1,000) per infusion for an average patient |

| Adalimumab (Humira) | 40 mg subcutaneously every 1 to 2 weeks | Pulmonary, neurologic, cutaneous,† renal‡ | Infections (especially reactivation of TB), allergic reactions | TB assessment at initiation; close monitoring during injections | NA ($6,800 per week or $3,400 every 2 weeks) |

Severe and progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis warrants prompt referral for possible lung transplantation.62 Posttransplantation outcomes for sarcoidosis are similar to outcomes for other lung diseases, and a median survival benefit may be achieved for appropriately selected patients with high risk of short-term mortality.63–65 Although there have been reports of recurrent noncaseating granulomas in some lung allografts, these findings usually are not clinically relevant.66,67

Additional information about sarcoidosis is available from the Foundation for Sarcoidosis Research (https://www.stopsarcoidosis.org), a nonprofit organization dedicated to finding a cure, improving care for patients, and providing high-quality educational materials for patients, families, and physicians.

Data Sources: The terms sarcoid, sarcoidosis, and granulomatous diseases were searched alone and combined with the words lung, cardiac, eyes, extrapulmonary, therapy, and epidemiology in PubMed, Cochrane, the National Guideline Clearinghouse, Ovid, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: July 3, 2015, and February 2, 2016.

eFigure A courtesy of Dr. Sandra Osswald.