Am Fam Physician. 2024;109(1):19-29

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that can involve any organ. Ongoing dyspnea and dry cough in a young to middle-aged adult should increase the suspicion for sarcoidosis. Symptoms can present at any age and affect any organ system; however, pulmonary sarcoidosis is the most common. Extrapulmonary manifestations often involve cardiac, neurologic, ocular, and cutaneous systems. Patients with sarcoidosis can exhibit constitutional symptoms such as fever, unintentional weight loss, and fatigue. The early recognition and diagnosis of sarcoidosis are challenging because there is no diagnostic standard for testing, initial symptoms vary, and patients may be asymptomatic. Consensus guidelines recommend a holistic approach when diagnosing sarcoidosis that focuses on clinical presentation and radiographic findings, biopsy with evidence of noncaseating granulomas, involvement of more than one organ system, and elimination of other etiologies of granulomatous disease. Corticosteroids are the initial treatment for active disease, with refractory cases often requiring immunosuppressive or biologic therapies. Transplantation can be considered for advanced and end-stage disease depending on organ involvement.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous inflammatory disease that can affect any organ. Sarcoidosis commonly affects the lungs and lymph nodes, but the etiology is unknown. This disease is challenging to diagnose and treat due to limited high-quality, evidence-based data. This article discusses the current evidence on the evaluation and treatment of sarcoidosis.

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis affects people of all ages and races. The average age at diagnosis is between 44 and 56 years, with children rarely affected.1–4 Females are up to twice as likely to have sarcoidosis than males.2,5,6 In the United States, the annual incidence and prevalence are 8 to 11 and 60 to 100 per 100,000, respectively. Incidence and prevalence are higher in Black people for complex reasons requiring further study.5 The western United States has significantly lower rates of disease than the Northeast, Midwest, or South.5 Globally, incidence and prevalence estimates have been challenged, but they are reportedly highest in Sweden, the United States, and Canada and lowest in Asian countries.4,5,7–9 There is an estimated 60% to 70% heritability based on heterogenous studies across populations, suggesting a combination of genetic and environmental factors.10

Pathogenesis

The etiology of sarcoidosis is unknown. Leading theories suggest that sarcoidosis develops after exposure to a foreign antigen, such as bacteria or environmental agents (e.g., insecticides, silica, mold), in an individual with a genetic predisposition that triggers an inflammatory process.11 Suspected infectious agents include Propionibacterium acnes and Mycobacterium.12 The interaction between the innate and adaptive immune cells creates an influx of cytokines, triggering an aberrant immune response that leads to the formation of noncaseating granulomas in tissues and organs.13 Clearance of the antigen leads to remission, whereas the body's failure to clear the antigen leads to chronic disease.

Natural History

The disease course of sarcoidosis is variable. Approximately one-half of patients experience spontaneous remission after two years, with lower remission rates in later disease stages.14,15 One-third of patients may experience sarcoidosis progression at three years, as measured by deterioration in radiographic findings or pulmonary function. The patient's age at the time of diagnosis is associated with disease progression, with one study showing an increased risk of 4% for each additional year after diagnosis. The likelihood of progression was 20% in patients 50 years and older.14

Overall mortality in patients with sarcoidosis is similar to the general population.2 According to a large U.S. mortality database evaluating sarcoidosis as an underlying cause of death, the overall age-adjusted mortality rate is 3.1%.16 Predictors of mortality include stage 4 disease on chest radiography, pulmonary hypertension, or greater than 20% fibrosis on high-resolution computed tomography (CT).17 Mortality is higher in Black patients, particularly females; however, the influence of genetics and modifiable risk factors are not adequately understood to report race as an independent predictor of mortality.16–18

Clinical Presentation

The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis varies. Common presenting symptoms are outlined in Table 1.19,20 Pulmonary symptoms, including shortness of breath, dry cough, and chest pain, occur in 50% of symptomatic patients.19 Constitutional symptoms, including fatigue, unintentional weight loss, and fever, may occur in up to one-third of patients. One-third of patients with systemic sarcoidosis develop skin lesions. Cutaneous sarcoidosis generally presents as red-brown papules and plaques but can have many variations.19 Sarcoidosis can mimic other conditions, such as discoid lupus erythematosus (Figure 1A), lichenoid dermatitis (Figure 1B), infection (Figure 1C), and psoriasis (Figure 1D), or appear as deep subcutaneous nodules (i.e., Darier-Roussy sarcoid; Figure 1E). Other common extrapulmonary symptoms depend on organ involvement, including visual disturbance (e.g., anterior uveitis), sensory changes, palpitations, right upper quadrant pain, and jaundice. Up to 50% of patients are asymptomatic, with bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy identified incidentally on chest radiography.21

| Organ system | Occurrence (%) | Clinical findings | Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lungs and lymph nodes | > 90 | Dyspnea Fibrosis Nonproductive cough Pulmonary infiltrates Restrictive lung disease Lymphadenopathy (enlarged hilar and or paratracheal lymph nodes) | Chest radiography High-resolution chest CT Pulmonary function tests that include diffusion lung capacity for carbon monoxide Transbronchial biopsy Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration |

| Musculoskeletal | 25 to 39 | Arthritis Intramuscular lesions Myalgias and proximal muscle weakness | Creatine kinase MRI Muscle biopsy Radiography |

| Skin | 20 to 30 | Erythema nodosum Lupus pernio Papules, nodules, plaques | Skin biopsy as needed |

| Eyes | 20 to 25 | Conjunctivitis Dacryoadenitis Sicca symptoms Uveitis | Annual ophthalmologic examination |

| Heart | 10 to 20 | Cardiomegaly Conduction abnormalities Congestive heart failure/arrhythmias Palpitations Pulmonary hypertension Sudden death | Electrocardiography Echocardiography Holter monitor Cardiac MRI Fluorodeoxyglucose positron-emission CT Right heart catheterization |

| Kidney | 5 to 10 | Decreased kidney function nephrolithiasis/hypercalciuria | Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine 24-hour urine for calcium excretion Referral to nephrology |

| Liver and spleen | 10 to 20 | Cirrhosis Consequences of splenic enlargement Hepatosplenomegaly Transaminitis | Liver function tests Abdominal/pelvic CT Liver biopsy |

| Nervous system | 10 to 25 | Neuropathies: cranial, spinal cord, peripheral, small fiber | Brain MRI Lumbar puncture Nerve conduction studies Referral to a neurologist |

| Endocrine | 5 to 10 | Hypercalcemia Pituitary or thyroid dysfunction | Thyroid function tests Expanded hormone testing when clinically indicated |

| Upper respiratory tract | 5 to 10 | Nasal congestion Parotitis Sinusitis Stridor | Referral to otolaryngologist and/or dedicated imaging |

| Hematologic | 4 to 40 | Eosinophilia Hypergammaglobulinemia Lymphopenia | Complete blood count Serum protein electrophoresis Bone marrow biopsy |

Diagnosis

| Organ system | Infectious differential diagnoses | Noninfectious differential diagnoses |

|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system | Bacteria: tuberculosis, Brucella Fungi: Aspergillus, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis Parasites: amoeba, toxoplasmosis, schistosomiasis, Taenia solium, Echinococcus, paragonimiasis Viruses: varicella zoster, herpes simplex | IgG4-related disease Chronic variable immunodeficiency Rosai-Dorfman disease Histiocytosis: Erdheim-Chester, histiocytosis X Lymphomatoid granulomatosis Granulomatosis with polyangiitis Rheumatoid nodules Amyloidosis Cholesterol granuloma Foreign body Drugs/toxins/heavy metals Sarcoid-like reaction to tumor CNS malignancies ranging from glioblastoma to lymphoma |

| Eyes | Parinaud oculoglandular syndrome: Bartonella, Francisella Bacteria: tuberculosis, syphilis Viruses: cytomegalovirus. varicella zoster, toxoplasmosis | Inflammatory bowel disease ANCA vasculitides Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease Blau syndrome |

| Sinonasal | Bacteria: tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteria, Klebsiella rhinoscleromatis, syphilis Fungi: Aspergillus flavus, histoplasmosis Parasites: leishmaniasis, rhinosporidiosis | Granulomatosis polyangiitis Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis Cholesterol granuloma NK/T-cell lymphoma Foreign body Drugs/toxins: cocaine, narcotics |

| Parotid/salivary/lacrimal glands | Bacteria: tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteria | Granulomatosis polyangiitis Ductal obstruction Crohn's disease |

| Heart | Bacteria: tuberculosis, syphilis, Tropheryma whipplei Fungi: Aspergillus | Giant cell myocarditis Acute rheumatic heart disease Granulomatosis with polyangiitis Erdheim-Chester Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia Foreign body Drugs/toxins Granulomatous lesions of unknown significance |

| Spleen | Bacteria: tuberculosis Fungi: histoplasmosis Parasites: leishmaniasis | Chronic variable immunodeficiency Sarcoid-like reaction to tumor |

| Kidney | Bacteria: tuberculosis Fungi: histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis Viral: adenovirus | Granulomatosis polyangiitis Chronic lymphocytic leukemia Drugs: allopurinol, antivirals, anti-convulsants, beta-lactams, diuretics, erythromycin, fluoroquinolones, NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors, rifampin, sulfonamides, vancomycin |

| Muscle | Bacteria: tuberculosis, syphilis, Brucella Fungi: Pneumocystis jirovecii, cryptococcosis Pneumocystis jirovecii Virus: human T-lymphotropic virus 1 | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma Crohn's disease Thymoma-myasthenia gravis Foreign body Primary biliary cirrhosis (primary biliary cholangitis) Cryofibrinogenemia |

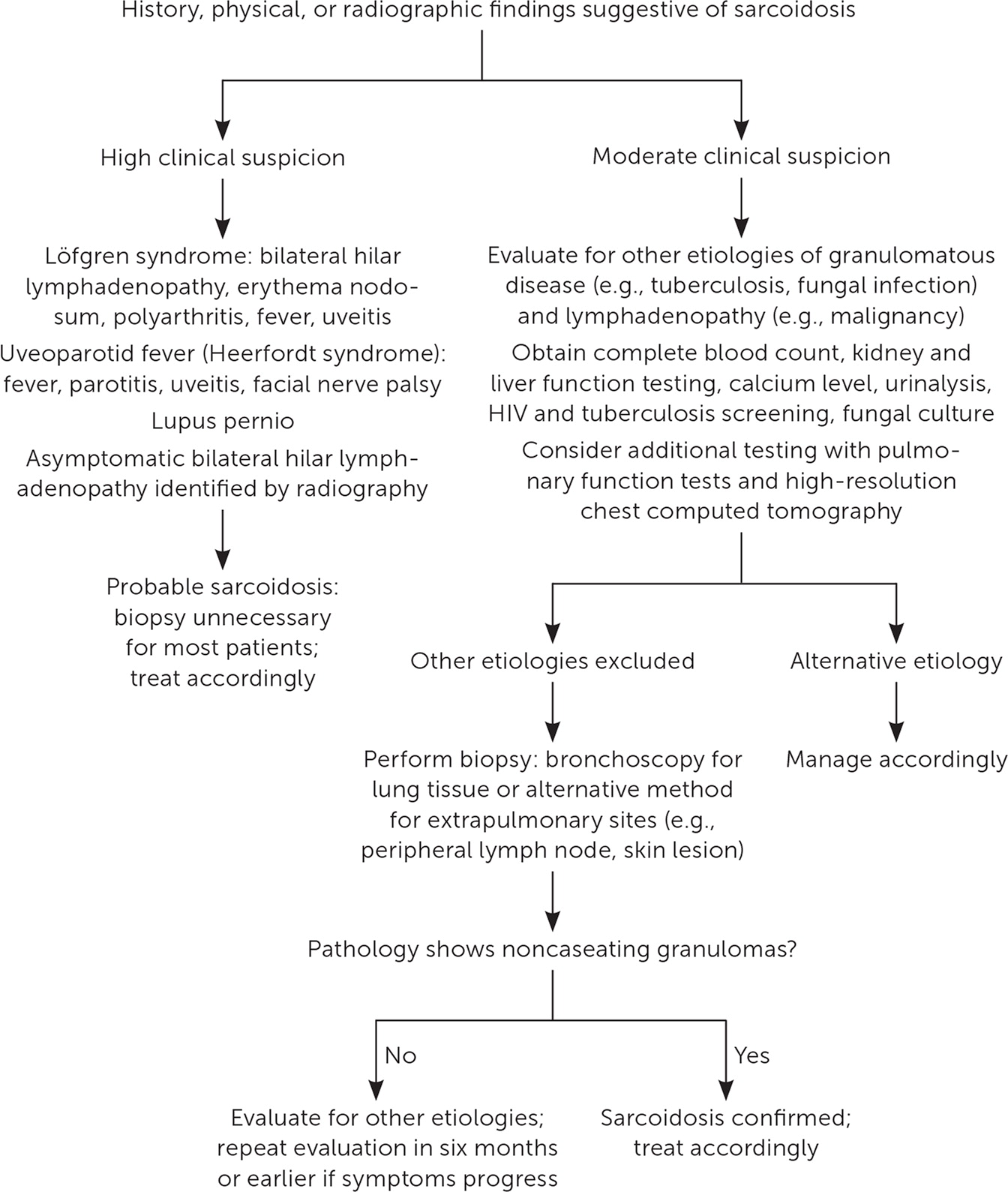

Sarcoidosis is a diagnostic challenge because there is no diagnostic standard for testing, the potential exists for an asymptomatic state, multiple organ systems can be affected, and clinical presentation can overlap with other pulmonary processes.21,23,24 Consensus guidelines suggest a holistic diagnostic approach, including elements of clinical presentation and radiographic findings, biopsy-proven noncaseating granuloma, involvement of more than one organ system, and exclusion of other etiologies of granulomatous disease.22,25,26 Figure 2 is an algorithm for the evaluation of patients with suspected sarcoidosis.19,22,24,25

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Baseline laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count, kidney function testing, liver function testing, electrolyte levels (including calcium), and urinalysis to screen for extrapulmonary involvement and exclude other etiologies.19,23,27 Additional testing may include tuberculosis screening, HIV, and fungal culture depending on patient-specific risk factors (e.g., exposure, travel, geographic location). Approximately 3% to 12% of patients with sarcoidosis have hypercalcemia secondary to increased circulating levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol) from macrophages within granulomas.27,28 Serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) concentrations are elevated in 50% to 60% of patients with sarcoidosis but have limited use in the diagnosis due to a lack of specificity, failure to correlate with radiographic disease severity, and genotypic interindividual variability.25,29,30 Elevated ACE levels have also been reported in infectious processes (e.g., leprosy, tuberculosis, pneumoconiosis), Hodgkin lymphoma, environmental exposures (e.g., asbestosis, berylliosis), and endocrine disorders (e.g., diabetes mellitus, hyperthyroidism).27,31

PULMONARY SARCOIDOSIS

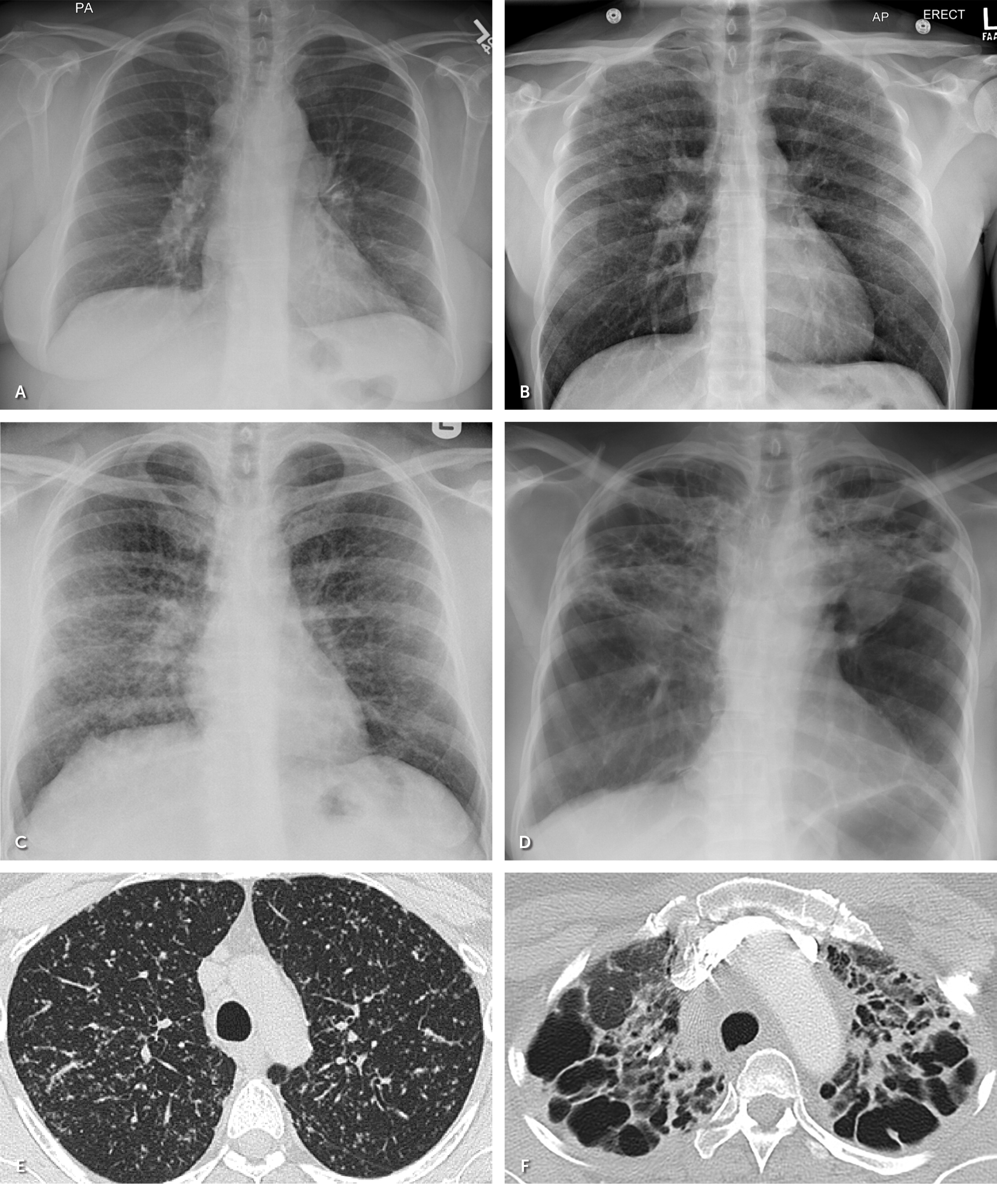

Approximately 80% to 90% of patients with biopsy-confirmed pulmonary sarcoidosis have abnormalities on radiography, most commonly bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy.24,27 The Scadding staging system was developed based on chest radiographic features for prognostic purposes 23,32,33 (Figure 3). High-resolution CT typically shows upper lobe lymphatic and peribronchovascular nodules and subcarinal and hilar lymphadenopathy.23,24 Unlike chest radiography, high-resolution CT closely inspects lung parenchyma to aid in quantifying lung fibrosis, which can affect treatment decisions and prognosis. High-resolution CT can identify the best peripheral lymph nodes for tissue sampling if a diagnosis is uncertain.23,27

Pulmonary function testing has normal findings in approximately 80% of patients without parenchymal infiltrates on imaging.27 Abnormal pulmonary function test patterns vary in sarcoidosis, depending on the distribution of airway inflammation, and include obstructive (commonly found in fibrotic disease), decreased diffusing capacity, and restrictive.23,24,34

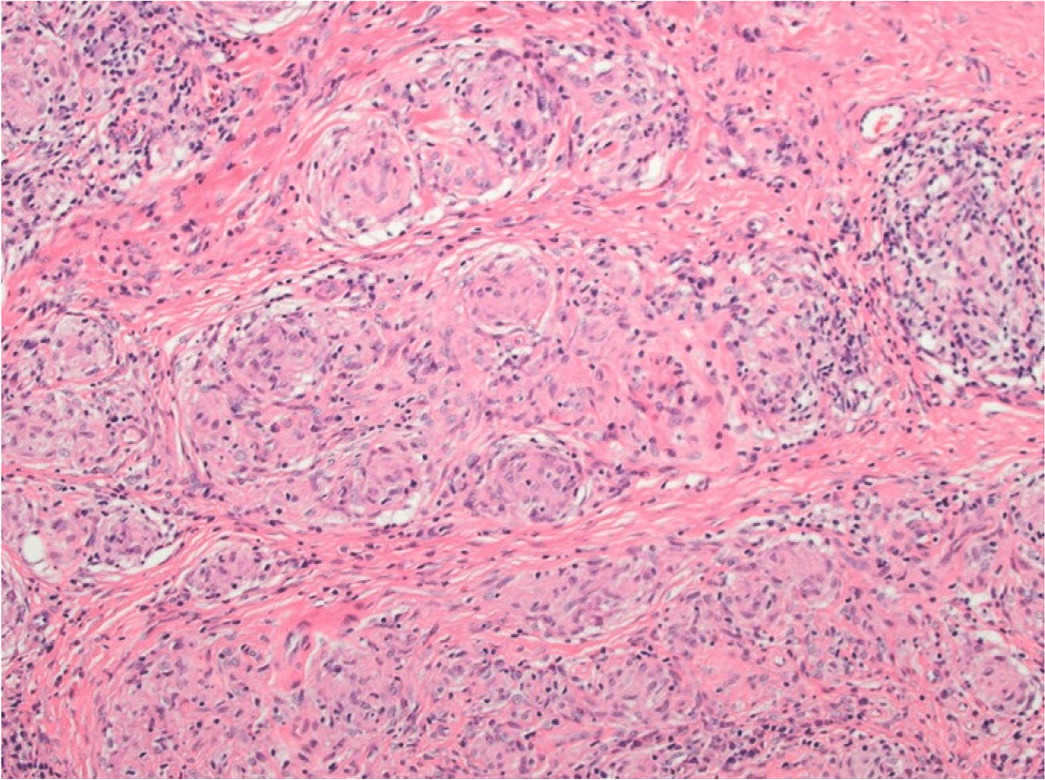

A tissue biopsy of cutaneous lesions or peripheral lymph nodes is the least invasive and safest option for diagnosis. Histopathologic findings of sarcoidosis are characterized by noncaseating granulomas consisting of aggregates of epithelioid histiocytes, giant cells, and mature macrophages35 (Figure 4). Lymphocyte composition is primarily CD4 T cells and a few CD8 lymphocytes. Patients without peripheral lesions may require bronchoscopy procedures such as transbronchial biopsy and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration, which is 80% to 90% sensitive, with complication rates of less than 1%.23,27,36 Bronchoalveolar lavage shows lymphocytosis and a CD4: CD8 T-cell ratio greater than 3.5 but low sensitivity (53% to 59%).24

EXTRAPULMONARY SARCOIDOSIS

All patients with a sarcoidosis diagnosis should undergo baseline 12-lead electrocardiography to screen for cardiac involvement.22,25,37 Abnormal findings, such as a higher degree heart block, right bundle branch block, or arrhythmias, should prompt additional evaluation with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or cardiac fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT. Advanced cardiac imaging usually provides sufficient diagnostic information, avoiding the need for endomyocardial biopsy.37 Additional cardiac testing includes a Holter monitor, echocardiography, and right heart catheterization if there is a concern for sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension.24

If neurosarcoidosis is suspected, a brain MRI and cerebrospinal fluid analysis with lumbar puncture should be performed. Cerebrospinal fluid findings are often nonspecific but support an inflammatory process consistent with sarcoidosis.38 Clinical guidelines recommend a baseline eye examination for a ll patients with sarcoidosis, and ongoing visual changes should prompt further evaluation.22,39 Under diascopy, in which pressure induces blanching, cutaneous lesions are yellow-orange. Dermoscopy of sarcoidosis shows multiple linear and branching vessels over translucent yellow-orange globular structures.40 Scar-like depigmented areas can also be seen on dermoscopy.

Several clinical syndromes are pathognomonic for sarcoidosis and do not require a confirmatory tissue biopsy.22 Lupus pernio is a type of cutaneous sarcoidosis associated with a poor prognosis and lung involvement (Figure 5). Lupus pernio rarely resolves spontaneously and may cause disfigurement, nasal obstruction, and fibrotic pulmonary complications due to extensive involvement of the nasal cavity and maxillary sinus.41 Löfgren syndrome is associated with a favorable prognosis and is characterized by erythema nodosum, uveitis, fevers, polyarthritis, and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy. Uveoparotid fever (Heerfordt syndrome) is characterized by uveitis, parotitis, fever, and occasionally facial nerve palsy.42

Treatment

PULMONARY SARCOIDOSIS

Patients with no symptoms or mild disease should be observed without treatment because spontaneous resolution is common.26 Oral corticosteroids are considered first-line therapy, and the decision to administer them should consider the patient's quality of life, degree of disability, and extent of lung involvement.43 A Cochrane review of 13 studies (n = 1,066 participants) found that patients treated with corticosteroids had improvements in chest radiograph appearance, symptoms, and spirometry over three to 24 months.44 However, corticosteroids do not appear to improve mortality, lung function, or disease progression.26,43

The optimal dosage of corticosteroids has not been established; dosing requires balancing the disease response vs. the risk of adverse effects.45 An initial prednisone dosage of 0.5 to 1.0 mg per kg per day (usually 20 to 40 mg per day) can be considered. An international consensus statement recommends a starting dosage of 20 to 40 mg of prednisone per day for four to six weeks. After one to three months of treatment, patients should be assessed every three to six months to evaluate the clinical response and disease progression by symptoms, pulmonary function testing, and chest radiography.26,46 Patients who do not respond to steroid therapy by three months are unlikely to benefit from a longer course of therapy. For disease responsive to steroid treatment, the dosage is slowly tapered to 5 to 10 mg per day or every other day for at least 12 months. There are no reliable biomarkers to aid in assessing treatment response.26

Corticosteroid-related adverse effects should be regularly assessed. Disease relapse following the cessation of corticosteroid treatment is not uncommon and most often occurs within the first two to six months following treatment.

Methotrexate is a second-line medication for patients with symptomatic pulmonary sarcoidosis who are thought to be at higher risk of future mortality or permanent disability.43,46 Methotrexate is indicated for patients with continued disease despite corticosteroid treatment or with unacceptable adverse effects from corticosteroid therapy.43 Azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and hydroxychloroquine have been used as alternative treatments.26 However, a Cochrane review evaluating these immunosuppressive and cytolytic agents in the treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis did not recommend the use of these medications and noted the potential for life-threatening adverse effects.47 Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, such as infliximab, are recommended in patients with persistent symptoms despite treatment with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents.48,49

In severe and progressive pulmonary sarcoidosis, prompt referral for possible lung transplantation is appropriate.50–52 Disease recurrence is possible in the transplanted lung, although it is usually asymptomatic and may not affect the patient's overall survival.53,54 Patients undergoing lung transplantation because of sarcoidosis have similar survival compared with patients undergoing lung transplant for other indications, with a reported 10-year posttransplant survival rate of 53%.55,56

EXTRAPULMONARY SARCOIDOSIS

The treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis involves the management of any left ventricular dysfunction, following established guidelines for heart failure with or without reduced ejection fraction. Corticosteroids may improve long-term clinical outcomes, including decreased all-cause mortality, symptomatic arrhythmias, and heart failure admissions.57,58 Corticosteroids may resolve atrioventricular block in patients with cardiac sarcoidosis. The addition of methotrexate to corticosteroids may improve cardiac function.59,60 Surgical options include an implantable cardioverterdefibrillator, pacemaker, radiofrequency catheter ablation, and heart transplantation; however, recurrence is possible after a transplant.61–63

Corticosteroids are considered first-line treatment for clinically significant neurosarcoidosis. Methotrexate can be added to corticosteroids for patients who continue to have symptoms of the disease.43,64 In patients with significant symptoms of disease despite treatment with a corticosteroid and the addition of methotrexate or other second-line agent (e.g., azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil), the addition of infliximab can be considered.43,48,49,65–67 Surgical intervention may be effective for hydrocephalus.68 Radiation can be considered, although variable outcomes are reported.69

Erythema nodosum usually resolves in six to eight weeks with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or a course of corticosteroids.26 Antimycobacterial therapy may reduce the size of chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis lesions.70 Topical corticosteroids are generally considered beneficial for limited skin lesions of mild disease, although evidence for their use is lacking.43,71–73 Intralesional corticosteroid injections may be an effective alternative for limited disease.74–76 In patients with cutaneous skin lesions that do not respond to topical treatments, oral corticosteroids can be considered. However, steroid-sparing regimens should be considered for chronic lesions such as lupus pernio.43 Antimalarial therapy (e.g., hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine), methotrexate, tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, thalidomide, and Janus kinase inhibitors are immunosuppressive therapies that can be considered in the treatment of cutaneous sarcoidosis.77–81

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Soto-Gomez, et al.19; Wu and Schiff82; and Belfer and Stevens.83

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms sarcoidosis and granulomatous disease alone and combined with extrapulmonary, pulmonary, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, cutaneous, cardiac, and neurosarcoidosis. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, DynaMed, and the Cochrane database. We critically reviewed studies that used patient categories such as race or gender but did not define how these categories were assigned, stating their limitations in the text. Reference lists of retrieved articles were also searched. Search dates: October 2022 to January 2023, and October 2023.

Figure 1B to 1D and Figure 5A courtesy of Penn State Health Department of Dermatology.

Figure 1E courtesy of Mikael Horrissian, MD, Penn State Health Department of Dermatology.

Figure 3 courtesy of Rekha A. Cherian, MBBS, Penn State Health Department of Radiology.

Figure 5B courtesy of Payvand Kamrani, DO, Penn State Health Department of Dermatology.