Am Fam Physician. 2024;109(1):34-42

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is defined as reduced blood flow to the coronary myocardium manifesting as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction or non–ST-segment elevation ACS, which includes unstable angina and non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Common risk factors include being at least 65 years of age or a current smoker or having hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, a body mass index greater than 25 kg per m2, or a family history of premature coronary artery disease. Symptoms most predictive of ACS include chest discomfort that is substernal or spreading to the arms or jaw. However, chest pain that can be reproduced with palpation or varies with breathing or position is less likely to signify ACS. Having a prior abnormal cardiac stress test result indicates increased risk. Electrocardiography changes that predict ACS include ST depression, ST elevation, T-wave inversion, or presence of Q waves. No validated clinical decision tool is available to rule out ACS in the outpatient setting. Elevated troponin levels without ST-segment elevation on electrocardiography suggest non–ST-segment elevation ACS. Patients with ACS should receive coronary angiography with percutaneous or surgical revascularization. Other important management considerations include initiation of dual antiplatelet therapy and parenteral anticoagulation, statin therapy, beta-blocker therapy, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor therapy. Additional interventions shown to reduce mortality in patients who have had a recent myocardial infarction include smoking cessation, annual influenza vaccination, and cardiac rehabilitation.

Each year, acute coronary syndrome (ACS) affects more than 7 million people globally.1 ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is responsible for 30% of cases, whereas non–ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTE ACS) accounts for the remaining 70%.2 Common risk factors include being at least 65 years of age or a current smoker or having hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, a body mass index greater than 25 kg per m2, or a family history of premature coronary artery disease (CAD).3 The most common symptom of ACS is acute chest pain, which accounts for approximately 1% of primary care visits and 5% of emergency department visits each year.4,5

| The 2021 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines no longer recommend classifying chest pain as atypical or typical, because this classification is not useful for identifying the cause and has been misused to classify chest pain as benign. Instead, the guidelines now recommend that chest pain be classified as cardiac, possibly cardiac, or noncardiac. |

| A systematic review of home-based cardiac rehabilitation studies demonstrated higher patient adherence to home-based cardiac rehabilitation, and that home-based and outpatient cardiac rehabilitation achieved similar improvement in functional capacity, quality of life, and coronary artery disease risk factor control after 12 months. |

| Despite the high prevalence of depression in patients with acute coronary syndrome, evidence suggests that there is minimal benefit to screening for depression in patients who have had a myocardial infarction within the past 12 months. |

Pathophysiology

Definitions

STEMI is heart muscle damage confirmed with elevated troponin levels and ST-segment elevation on electrocardiography (ECG). NSTE ACS includes unstable angina (chest pain at rest with possible changes on ECG but without an elevated troponin level) and non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, which is heart muscle damage confirmed diagnostically using elevated troponin levels and ECG changes without ST-segment elevation.

Initial Evaluation

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Crushing, substernal chest discomfort is the typical presentation of ACS. The pain may spread to one or both arms or the jaw. It may be caused by exertion and associated with nausea, emesis, and diaphoresis. Men and women report symptoms with a significant overlap in presentation, and chest discomfort is the most common symptom for both.2,8 However, women may be more likely to experience accompanying nausea, pain that spreads to the shoulders, and shortness of breath.2,9,10 Studies comparing symptom presentations of men and women did not explicitly state how participant sex was identified. It should be noted that any disparities observed between men and women are likely driven by bias, or other factors aside from the symptom profile. Patients who are at least 65 years of age or have diabetes mellitus may be more likely to report shortness of breath instead of chest pain as their initial symptom6 and may also report vague abdominal pain.8

Symptoms most predictive of ACS include classic symptoms of crushing, substernal chest pain (likelihood ratio [LR] = 1.9; 95% CI, 0.9 to 2.9) and pain spreading to the arms (LR = 2.6; 95% CI, 1.8 to 3.7). Having a prior abnormal stress test result (LR = 3.1; 95% CI, 2.0 to 4.7) indicates higher risk of ACS. The likelihood of ACS is reduced when the patient reports chest pain that varies with breathing or position (LR = 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4 to 0.6) or pain that can be reproduced with chest palpation (LR = 0.3; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.5).7,11

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS FOR CHEST PAIN

Chest pain is the most commonly reported symptom for ACS, but the condition is only diagnosed in 2% to 4% of patients who present with this symptom.12,13 Other common causes of chest pain include stable angina (10%), chest wall pain or costochondritis (20% to 50%), gastroesophageal reflux (10% to 15%), and somatic discomfort (7.5%).12 Other emergent or life-threatening etiologies to consider include pulmonary embolism, aortic dissection, esophageal rupture, and tension pneumothorax.2,8

The 2021 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association guidelines no longer recommend classifying chest pain as atypical or typical, because this classification is not useful for identifying the cause and has been misused to classify chest pain as benign.8 Instead, the guidelines now recommend that chest pain be classified as cardiac, possibly cardiac, or noncardiac.

RISK ASSESSMENT

There is no validated clinical decision tool with sufficient sensitivity to safely rule out ACS in the outpatient setting.14 However, outpatient clinicians can use the Marburg Heart Score to assess the likelihood of cardiac origin for intermittent chest pain15 (Table 18,11,16,17). This tool can help triage patients with intermittent chest pain who need more urgent evaluation in the emergency department. The tool uses a combination of age, sex, risk factors, and patient history to determine the likelihood that CAD is causing the patient's chest pain. ECG results are not considered.

| Category | Marburg Heart Score (outpatient) | Points | HEART Score (inpatient) | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indications | Intermittent chest pain in primary care patients | — | Acute chest pain in emergency department | — |

| Clinical history | Increased pain with exercise Pain not reproduced on chest wall palpation Patient assumes pain is of cardiac origin | 1 1 1 | Highly suspicious for ACS based on clinical judgement Moderately suspicious for ACS Slightly or not suspicious for ACS | 2 1 0 |

| Electrocardiography | NA | — | Significant ST depression Nonspecific repolarization Normal | 2 1 0 |

| Age | Women ≥ 65 years; men ≥ 55 years | 1 | ≥ 65 years 45 to 64 years < 45 years | 2 1 0 |

| Risk factors | Known vascular disease | 1 | ≥ 3 risk factors* 1 or 2 risk factors No known risk factors | 2 1 0 |

| Troponin levels | NA | — | > 3 times the normal limit 1 to 3 times the normal limit ≤ normal limit | 2 1 0 |

| Total points ___________ | Total points ___________ | |||

| Risk interpretation | ||||

| Low risk (at 6-month evaluation, LR of 0.04 that patient's chest pain is caused by underlying CAD) | 0 to 1 | Low risk (1.7% risk of MACE within 6 weeks) | 0 to 3 | |

| Intermediate risk (at 6-month evaluation, LR of 1 that patient's chest pain is caused by underlying CAD) | 2 to 3 | Intermediate risk (17% risk of MACE within 6 weeks) | 4 to 6 | |

| High risk (at 6-month evaluation, LR of 11 that patient's chest pain is caused by underling CAD) | 4 to 5 | High risk (50% risk of MACE within 6 weeks) | 7 to 10 |

A low Marburg Heart Score (0 to 2) correlates with a 3% likelihood of CAD being the cause of the patient's chest pain. A score of 3 or more correlates with a 23% likelihood of CAD being the cause of the patient's chest pain, and they should be transferred to the emergency department for more urgent evaluation. Compared with other outpatient clinical decision aids, the Marburg Heart Score has been shown to have increased sensitivity and specificity for identifying CAD as the cause of chest pain compared with clinical judgement alone.14

Several clinical decision tools estimate cardiac risk and mortality in the emergency department or inpatient setting; two common examples are the HEART Score and the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction risk score. The HEART Score is a clinical prediction tool designed to identify patients who warrant further workup for ACS based on their risk of major adverse cardiac events.11,16,18,19 For patients diagnosed with NSTE ACS, the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction risk score determines the pooled risk of subsequent ischemic events or death.11

Diagnostic Studies

ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHY

Electrocardiography should be performed in patients with possible cardiac chest pain.2,8 If ACS is suspected based on clinical judgement, priority should be given to transferring the patient immediately to the nearest emergency department over performing ECG. When ECG is performed in the outpatient clinical setting, it should be compared with the patient's baseline ECG results, if available, to assess for changes. For patients presenting to the emergency department, ECG should be performed within 10 minutes of arrival and followed with serial ECG tests, because 5% of patients with ACS may initially present with normal ECG results.20 Evidence of ischemia on ECG that predicts ACS includes T-wave inversions (LR = 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.7), presence of Q waves (LR = 3.6; 95% CI, 1.6 to 5.7), ST depression (LR = 5.3; 95% CI, 2.1 to 8.6), and ST elevation (LR = 3.6; 95% CI, 1.6 to 5.7).7,11,21 ECG findings that may obscure electrical changes signifying ischemia include the presence of a left bundle branch block, delta wave, or ventricular pacing.8

HIGH-SENSITIVITY CARDIAC TROPONIN

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin is an organ-specific, not disease-specific, biomarker. Measurement is typically ordered in the emergency department and is repeated because the level may not increase until several hours after the initial ACS event.22 Obtaining a creatinine kinase-myoglobin binding level with the high-sensitivity cardiac troponin level has little diagnostic use for confirming acute myocardial ischemia.23

IMAGING STUDIES

Physicians can consider using imaging studies, such as radiography of the chest, computed tomography of the chest, and point-of-care ultrasonography, if an alternative diagnosis to ACS is suspected.8 The use of point-of-care ultrasonography for echocardiography before coronary angiography as a diagnostic tool remains preliminary.24

STRESS TESTING AND CORONARY ANGIOGRAPHY

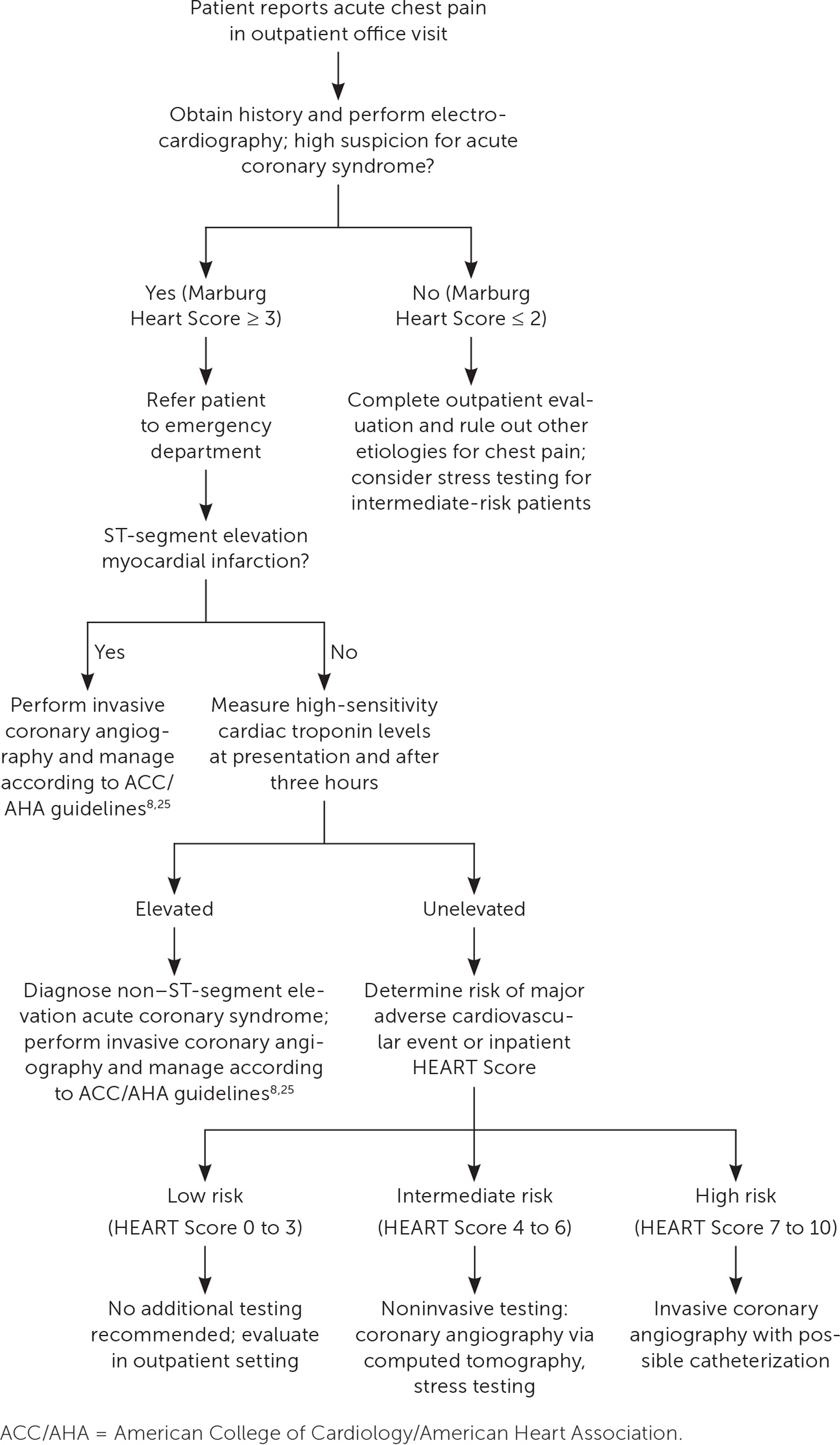

Once ACS is diagnosed, the next step is invasive coronary angiography for patients with STEMI, non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, or suspected NSTE ACS with high-risk indicators (Figure 18,13,14,25). Risk stratification can determine further testing for patients with suspected NSTE ACS without diagnostic ECG findings or elevated troponin levels. High risk warrants invasive angiography; intermediate risk warrants noninvasive testing (such as coronary computed tomography angiography or stress testing); and low risk does not warrant any further testing.2,6,8

Initial Management Steps

OUTPATIENT SETTING

If there is clinical suspicion of ACS in the outpatient setting, the patient should be immediately transferred by ambulance to the emergency department.

OUTSIDE OF THE HOSPITAL

Patients en route to the emergency department with suspected ACS should be placed on cardiac monitoring and receive 162 to 325 mg of aspirin. Supplemental oxygen should be administered for patients with a pulse oximetry reading less than 90%. Sublingual nitroglycerin, 0.4 mg as needed up to once every five minutes, should be given for relief of chest pain if no contraindications are present (e.g., hypotension, suspicion of posterior myocardial infarction).7

STEMI

Patients with STEMI should receive coronary angiography, followed by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with a drug-eluting stent within 120 minutes of presenting to the emergency department.2,25–27 If PCI cannot be performed within 120 minutes of diagnosis, fibrinolytics should be administered if there are no contraindications.26,28 Fibrinolytics have maximal benefit if administered within 120 minutes. After fibrinolytics are administered, patients should be transferred to a center capable of performing PCI.28

NSTE ACS

Patients with NSTE ACS should typically undergo coronary angiography. Following angiography, 60% of patients will receive PCI, 10% will undergo bypass surgery, and 30% will be managed with medical therapy alone.29 Patients who receive early invasive treatment have lower mortality, with high-risk patients receiving the largest mortality benefit.2,6,8,25,30

PHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

Antithrombotic therapy should be initiated in all patients presenting with ACS2,31–37 (Table 22,32). In the hospital, patients are usually started on aspirin, a P2Y12 inhibitor, and a parenteral anticoagulant (e.g., unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparin, direct thrombin inhibitors, or factor Xa inhibitors) and subsequently discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy. Patients on antithrombotic therapy should be monitored for bleeding, particularly gastrointestinal bleeding, in inpatient and outpatient settings. Dual anti-platelet therapy is typically continued for at least one year. Patients at high risk of bleeding may be eligible for a shorter duration; however, this determination should be made with cardiologist consultation.32

| Agent | Drug classification | Onset of action | Adverse effects | Maintenance dose per day* | Duration of therapy | Perioperative considerations | Contraindications | Common medication interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | Cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitor | < 1 hour without enteric coating 3 to 4 hours with enteric coating | Bleeding, gastrointestinal ulcers | 81 mg | Ongoing | Continue medication | Aspirin allergy; consider providing desensitization | ACE inhibitors, anticoagulants, CCBs (nondihydropyridine), loop diuretics, multi-vitamins, NSAIDs, SSRIs, steroids |

| Clopidogrel | P2Y12 inhibitor | 2 to 4 hours | Bleeding, rash, diarrhea | 75 mg | 1 year† | Hold 5 days before surgery | Severe bleeding | Anticoagulants, bupropion, CCBs, morphine, multivitamins, NSAIDs, PPIs, P2Y12 inhibitors, SSRIs |

| Prasugrel (Effient) | P2Y12 inhibitor | 30 to 60 minutes | Bleeding, hypertension, headache | 10 mg | 1 year† | Hold 7 days before surgery | History of stroke or transient ischemic attack | Anticoagulants, multivitamins, NSAIDs, P2Y12 inhibitors, SSRIs |

| Ticagrelor (Brilinta) | P2Y12 inhibitor | 30 minutes | Bleeding, bradyarrhythmia, dyspnea | 90 mg twice daily | 1 year† | Hold 5 days before surgery | Use with caution in patients with baseline dyspnea | Anticoagulants, multivitamins, NSAIDs, P2Y12 inhibitors, statins, SSRIs |

Approximately 5% to 10% of patients with ACS have concomitant atrial fibrillation. Long-term oral anticoagulation medication is typically required in these patients, which increases the risk of bleeding when combined with a P2Y12 inhibitor and aspirin. Based on two randomized-controlled trials, it is recommended that patients with atrial fibrillation take aspirin with oral anticoagulation medication and a P2Y12 inhibitor for up to four weeks after PCI, then discontinue aspirin. One year after PCI, patients should take only oral anticoagulation medication to reduce the risk of future bleeding events without increasing the risk of future ischemic events.8,38

Other pharmacologic management considerations for ACS are listed in Table 3.2,39–48 Patients with a recent myocardial infarction may be eligible for statin therapy, beta-blocker therapy, and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor therapy. Although the optimal duration of beta-blocker therapy after ACS is unknown, studies suggest that it can be reevaluated in two to three years if there are no other indications for beta-blocker therapy and patients are experiencing adverse effects.39

| Medication | Special indications | Target daily dose* | Contraindications | Adverse effects | Monitoring and testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statins | Recommended for all patients | High-intensity dosing: atorvastatin 40 or 80 mg; rosuvastatin 20 or 40 mg | Active liver disease or severely elevated liver transaminase levels (> 3 to 5 times the normal limit) | Arthralgia, elevated liver transaminase levels, gas-trointestinal symptoms, headache, myalgias | Obtain LFTs and lipid panel before initiation, consider creatine kinase levels in patients with symptoms of myopathy |

| Ezetimibe | Consider in patients already on maximally tolerated statin dose with low-density lipoprotein > 70 mg per dL (1.81 mmol per L) | 10 mg | Active liver disease | Elevated hepatic enzymes | Obtain LFTs and lipid panel before initiation |

| Beta blockers | Recommended for all patients; consider strongly if reduced LVEF | Various; consider stopping after 2 to 3 years if patient has adverse effects and no other indications | Second- or third-degree heart block, severe bradycardia | Bronchospasm, decreased heart rate, depression, fatigue, hypoglycemia, sexual dysfunction | Monitor heart rate, consider discontinuation in patients with symptomatic bradycardia |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | Consider if patient has reduced LVEF or diabetes mellitus; ARB/neprilysin inhibitor may be preferred if LVEF < 40% | Various | History of anaphylaxis or angioedema | Cough/angioedema (more common with ACE inhibitor), hyperkalemia, hypotension, reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate | Monitor blood pressure, recommend obtaining BMP before initiation and while on therapy; consider complete blood count for patients with underlying chronic kidney disease |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | Consider if LVEF < 40% | Spironolactone 12.5 or 25 mg; eplerenone 25 or 50 mg | Potassium level > 5.5 mEq per L (5.5. mmol per L) or CrCl < 30 mL per minute | Decreased libido, fatigue, gynecomastia, headache, hyperkalemia, menstrual irregularities | Monitor blood pressure and hydration status; obtain BMP and uric acid measurement before initiation and while on therapy |

| SGLT2 inhibitor | Consider for all patients; consider strongly for those with diabetes or heart failure regardless of LVEF | Empagliflozin (Jardiance) 10 or 25 mg; dapagliflozin (Farxiga) 5 or 10 mg | CrCl < 45 mL per minute for dapagliflozin; CrCl < 30 mL per minute for empagliflozin | Acute kidney injury, euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis, genitourinary tract infections, hypotension | Monitor blood pressure and hydration status, obtain BMP before initiation and while on therapy |

| GLP-1 agonist | Consider if patient has diabetes | Various | Medullary thyroid cancer, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2, pancreatitis | Acute kidney injury, gastrointestinal discomfort, gallbladder disease, pancreatitis | Consider obtaining BMP and A1C level before initiation and while on therapy |

NONPHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

For patients who cannot participate in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation services, home-based cardiac rehabilitation may be an option. A systematic review of home-based cardiac rehabilitation studies demonstrated that patient adherence is higher at home, but home-based and outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programs achieved similar improvement in functional capacity, quality of life, and CAD risk factor control for patients after 12 months.53 Evidence did not consistently show benefits of home-based cardiac rehabilitation beyond 12 months.53 Third-party reimbursement discrepancies represent a major barrier to implementation of home-based cardiac rehabilitation.

Approximately 10% of patients with ACS will subsequently experience symptoms that are consistent with major depressive disorder.54 Despite the high prevalence of depression in patients with ACS, evidence suggests that there is only minimal benefit in screening for depression in patients who have had a myocardial infarction within the past 12 months.55

Recurrent cardiac events are common; up to 20% of patients experience a future ACS event within four years.2

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Switaj, et al.,56 Barstow, et al.,57 Achar, et al.,58 and Wiviott and Braunwald.59

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms unstable angina, acute coronary syndrome, NSTEMI, and STEMI. The search included meta-analyses, randomized-controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports, the Cochrane database, DynaMed, and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. We critically reviewed studies that used patient categories such as race and/or gender but did not define how these categories were assigned, stating their limitations in the text. Search dates: April 18 and November 29, 2023.