Am Fam Physician. 2024;109(1):43-50

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Asthma exacerbations, defined as a deterioration in baseline symptoms or lung function, cause significant morbidity and mortality. Asthma action plans help patients triage and manage symptoms at home. In patients 12 years and older, home management includes an inhaled corticosteroid/formoterol combination for those who are not using an inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting beta2 agonist inhaler for maintenance, or a short-acting beta2 agonist for those using an inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting beta2 agonist inhaler that does not include formoterol. In children four to 11 years of age, an inhaled corticosteroid/formoterol inhaler, up to eight puffs daily, can be used to reduce the risk of exacerbations and need for oral corticosteroids. In the office setting, it is important to assess exacerbation severity and begin a short-acting beta2 agonist and oxygen to maintain oxygen saturations, with repeated doses of the short-acting beta2 agonist every 20 minutes for one hour and oral corticosteroids. Patients with severe exacerbations should be transferred to an acute care facility and treated with oxygen, frequent administration of a short-acting beta2 agonist, and corticosteroids. The addition of a short-acting muscarinic antagonist and magnesium sulfate infusion has been associated with fewer hospitalizations. Patients needing admission to the hospital require continued monitoring and systemic therapy similar to treatments used in the emergency department. Improvement in symptoms and forced expiratory volume in one second or peak expiratory flow to 60% to 80% of predicted values helps determine appropriateness for discharge. The addition of inhaled corticosteroids, consideration of stepping up asthma maintenance therapy, close follow-up, and education on asthma action plans are important next steps to prevent future exacerbations.

Asthma is a major public health problem that affects as many as 262 million children and adults globally and causes significant morbidity, mortality, and economic burden.1 Approximately 40% of patients with asthma have an exacerbation in their lifetime. Asthma exacerbations are responsible for more than 1.8 million emergency department visits and nearly 170,000 hospital admissions per year.2 Risk factors for exacerbations include poor symptom control, an exacerbation in the past year, poor medication adherence, incorrect inhaler technique, chronic sinusitis, and smoking.3–5 These risk factors can be appropriately managed in a primary care setting.6 Evaluation and management of asthma exacerbations vary across settings, including at home, in the office, in the emergency department, and during hospitalization. Physicians should provide careful postdischarge planning and follow-up. Recommendations for the evaluation and management of acute asthma exacerbations are based on the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) and National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) guidelines.

| Single maintenance and reliever therapy (SMART) is the preferred choice for moderate to severe asthma in adults and adolescents because it reduces the risk of exacerbations. Guidelines recommend the use of an ICS/LABA for SMART therapy, with formoterol as the preferred LABA for this approach. |

| A 2018 systematic review of nine studies found that school-based, supervised asthma intervention programs in urban areas improved multiple asthma-related outcomes, including fewer exacerbations requiring treatment with oral corticosteroids and decreased use of rescue inhalers. |

| A 2014 Cochrane review demonstrated that magnesium sulfate infusion modestly reduces hospitalizations in adults with severe asthma exacerbations. |

Diagnostic Criteria

An asthma exacerbation is a deterioration in baseline symptoms or lung function in patients with asthma. An exacerbation can be diagnosed based on subjective criteria, such as dyspnea, chest tightness, cough, and wheezing, and on objective information, such as decreased pulmonary function tests and oxygen saturation. Table 1 outlines the commonly used National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute definitions of asthma exacerbation severity, which are based on dyspnea and decreases in peak expiratory flow (PEF) or the forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1).7 An asthma task force recommendation, however, highlights the need for ongoing prospective research in the clinical setting, taking into account individual responses to treatment, because deterioration of symptoms, frequency of exacerbations, and lung function can vary among patients.8

| Severity | Symptoms and signs | Initial PEF (or FEV1) |

|---|---|---|

| Mild | Dyspnea only with activity (assess tachypnea in young children) | ≥ 70% of predicted or personal best |

| Moderate | Dyspnea interferes with or limits usual activity | 40% to 69% of predicted or personal best |

| Severe | Dyspnea at rest; interferes with conversation | < 40% of predicted or personal best |

| Life-threatening | Dyspnea prevents patient from speaking; perspiration | < 25% of predicted or personal best |

Early Recognition and Risk Reduction

The most successful strategy for prevention of acute asthma exacerbations includes early recognition, management, and treatment. It is important to identify patients at high risk. Exacerbations are typically triggered by viral upper respiratory tract infections and occur more often in patients with certain comorbid conditions, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease. Patients who have a history of asthma exacerbations are more likely to have another exacerbation.9 All patients with asthma should be educated on the risks, signs, symptoms, and management of exacerbations.10,11 Two of the most effective ways to facilitate early intervention and treatment of an acute asthma exacerbation are asthma action plans and school-based asthma management programs.12

ASTHMA ACTION PLANS

The goal of home asthma management is to control symptoms and reduce the risk of asthma-related morbidity (including exacerbations) and mortality. Guidelines recommend that all children and adults with asthma have a written asthma action plan so that they are prepared to act in response to worsening asthma. This is especially important for patients with moderate to severe asthma. According to a 2001 study, asthma action plans are associated with a 70% reduction in the risk of death.13 Asthma action plans for adults should include standard and individualized written instructions. They should address the use of inhaled and oral corticosteroids and include a minimum of two action points. Individualized instructions are based on personal best (i.e., signs and symptoms that are the most reliable indicators of impaired control or exacerbation for that patient or PEF).12 More information on asthma action plans is available at https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/actionplan.html and https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/asthma/treatment-action-plan.

SCHOOL-BASED APPROACH

A 2018 systematic review of nine studies found that school-based, supervised asthma intervention programs in urban areas improve multiple asthma-related outcomes, including fewer exacerbations requiring treatment with oral corticosteroids and decreased use of rescue inhalers.14 A 2013 randomized controlled trial that assessed 1,316 children in 130 public schools found that school-based asthma education programs decreased the use of urgent health care for asthma-related concerns.15

MEDICATIONS TO PREVENT EXACERBATIONS

Single maintenance and reliever therapy (SMART; also called MART) is the preferred choice for moderate to severe persistent asthma in adults and adolescents 12 years and older because it reduces the risk of exacerbations.16 Both GINA and NAEPP recommend the use of an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) combination for SMART, with formoterol as the preferred LABA because it has been studied the most.11,17,18 However, NAEPP limits the use of ICS/LABA combinations to steps 3 and 4 of treatment (moderate to severe persistent asthma) and recommends a short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA) as rescue medication for the other steps of treatment.19

A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis showed that, compared with dual therapy (ICS/LABA), triple therapy (ICS/LABA/long-acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA]) is associated with fewer severe asthma exacerbations (27.4% vs. 22.7%) in patients six years and older with moderate to severe asthma, although there was no difference in overall mortality.11,20

Management of Asthma Exacerbations

AT HOME

In patients 12 years and older who have mild asthma and are not using an ICS/LABA inhaler for maintenance, ICS/formoterol is the most studied option for acute symptoms, although this may be cost-prohibitive for some patients.11,22–24 Although a SABA may be used as a reliever inhaler, ICS/formoterol has been shown to reduce the risk of severe exacerbations.22–24 For adults and adolescents using an ICS/LABA inhaler that does not include formoterol, a SABA is the preferred choice for relief of acute symptoms.11 If asthma medications are used only sporadically, the physician should ensure the prescriptions are maintained and up-to-date.

There are no data to support using ICS/formoterol as a reliever inhaler for children younger than 12 years.18 However, in children four to 11 years of age with moderate to severe, persistent asthma, ICS/formoterol, up to eight puffs daily, can be used as SMART to reduce the risk of exacerbations.18 In patients with mild to moderate asthma, there is no evidence to suggest that increasing the use of ICS/formoterol decreases the use of oral corticosteroids.21

IN THE OFFICE

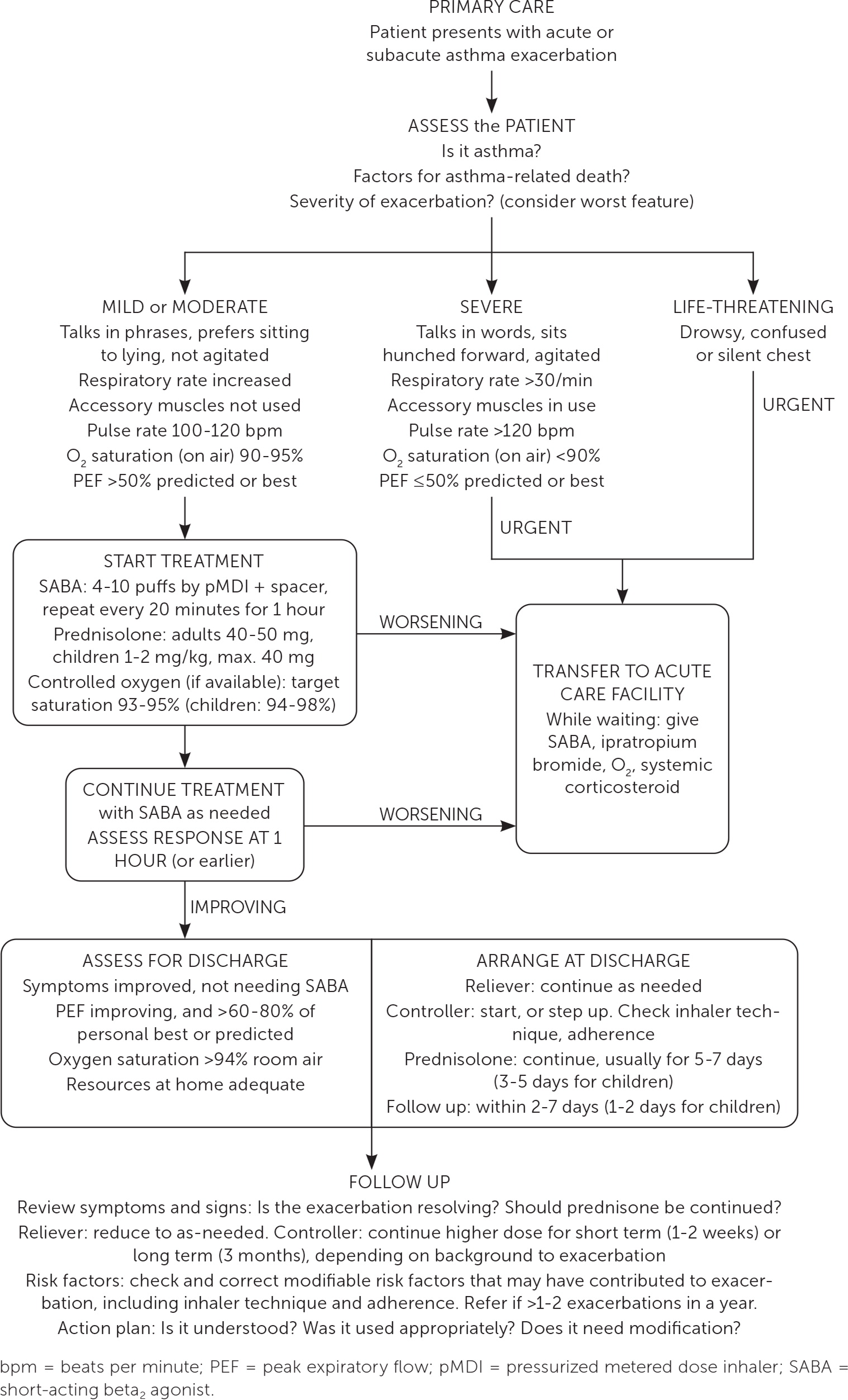

Managing an asthma exacerbation in the office setting begins with assessing the exacerbation severity, including dyspnea and vital signs, and starting a SABA and oxygen, if needed, to maintain oxygen saturations of greater than 93% in adolescents and adults and greater than 94% in children six to 12 years of age. Patients experiencing a severe asthma exacerbation should be transferred to an acute care facility, whereas patients with mild or moderate exacerbations should receive repeated doses of four to 10 puffs of a SABA every 20 minutes for one hour, with frequent evaluation of response to treatment.11 If available, oral corticosteroids should also be given. Figure 1 shows the pathway for the evaluation and management of in-office exacerbations.11

If symptoms improve and a SABA is no longer required, patients can be sent home with a regular controller or two to four weeks of current maintenance therapy at an increased dose. Adults and adolescents should follow up in the office within two to seven days and children within one to two working days.11

EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT

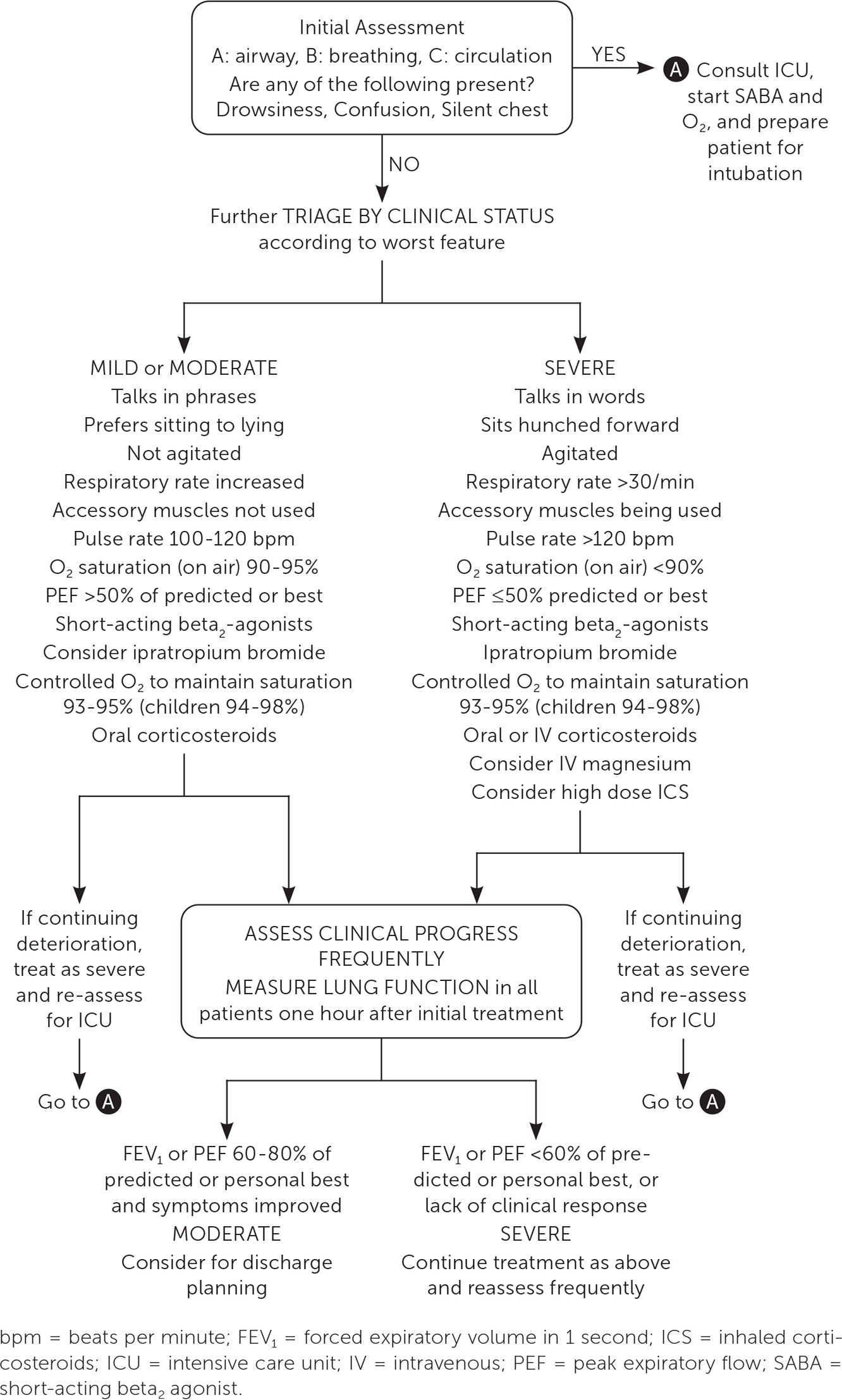

Severe or worsening asthma exacerbations may require treatment in the acute care setting (Figure 211). Assessment should include vital signs, oxygen saturation, cardiopulmonary examination, and PEF testing, even if completed before arrival in the emergency department.11 Initial assessment should also evaluate for severe features, such as hypoxia and drowsiness, or factors associated with an increased risk of asthma-related death (Table 211) that would warrant treatment in the acute care setting.25–30 Arterial blood gas measurements and chest radiography may be considered but are not routinely recommended.31,32 Alternative diagnoses, such as lower respiratory tract infections or foreign bodies, should be excluded.

| A history of near-fatal asthma requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation |

| Hospitalization or emergency care visit for asthma in the past year |

| Currently using or having recently stopped using oral corticosteroids (a marker of event severity) |

| Not currently using inhaled corticosteroids |

| Overuse of short-acting beta2-agonists (SABAs), especially use of more than one canister of salbutamol (or equivalent) monthly |

| Poor adherence with ICS-containing medications and/or poor adherence with (or lack of) a written asthma action plan |

| A history of psychiatric disease or psychosocial problems |

| Food allergy in a patient with asthma |

| Several comorbidities including pneumonia, diabetes and arrhythmias were independently associated with an increased risk of death after hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation |

Initial therapy includes oxygen administration to achieve saturation levels of 93% to 95% in adults and adolescents, which has been linked to better physiologic outcomes compared with achieving higher levels of oxygen saturation that may lead to hypercapnia.11,33 Inhalation therapy with a SABA should begin promptly, with repeated administration indicated by clinical response. Epinephrine should be administered if anaphylaxis or angioedema occurs. Oral corticosteroids should be administered within the first hour of presentation. Intramuscular or intravenous corticosteroids can be considered if the patient is unable to tolerate oral intake, but they are not superior to the oral route.34 Administration of high-dose ICS within the first hour of presentation may reduce the need for hospitalization.35 The addition of a short-acting muscarinic antagonist has also been associated with fewer hospitalizations.36 A 2014 Cochrane review demonstrated that magnesium sulfate infusions modestly reduce hospitalizations in adults with severe asthma exacerbations, and it can be considered in patients not responsive to initial therapies.11,37 Table 3 lists commonly used medications for asthma exacerbations in the acute care setting.7,11,35

| Medication | Dosage |

|---|---|

| Albuterol (nebulized) | Children |

| Initial: 0.15 mg per kg (minimum dose is 2.5 mg) every 20 minutes for three doses | |

| Subsequent: 0.15 to 0.3 mg per kg (up to 10 mg) every one to four hours as needed | |

| Adults | |

| Initial: 2.5 to 5 mg every 20 minutes for three doses | |

| Subsequent: 2.5 to 10 mg every one to four hours as needed | |

| Ipratropium (nebulized) | Children: 0.25 to 0.5 mg every 20 minutes for three doses and then as needed |

| Adults: 0.5 mg every 20 minutes for three doses and then as needed | |

| Oral corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone, methylprednisolone, prednisolone) | Children: 1 mg per kg in two divided doses (maximum dosage is 60 mg per day) |

| Adults: 40 to 80 mg per day in one or two divided doses | |

| Intramuscular epinephrine* (1 mg per mL) | Children: 0.01 mg per kg per dose every five to 15 minutes up to three doses (maximum dose for prepubertal children is 0.3 mg per dose; maximum dose for adolescents is 0.5 mg per dose) |

| Adults: 0.3 to 0.5 mg; may repeat every 20 minutes for three doses | |

| High-dose inhaled corticosteroids | If five years or older, 2 mg or greater of beclomethasone equivalent |

| Intravenous magnesium sulfate | 2-g infusion over 20 minutes |

Indications for hospitalization are based on clinical condition, spirometry, and medical history. Other factors to consider include the need for more than eight puffs of a bronchodilator in the past 24 hours, past hospitalization or intubation, and frequent emergency department or office visits.11,38 Continued oxygen requirements and inadequate response to bronchodilator therapy should prompt admission. A pretreatment FEV1 of less than 25% predicted value or posttreatment FEV1 of less than 40% predicted value is suggested as a threshold for admission criteria based on retrospective studies.39 Discharge criteria include improvement of symptoms and objective improvement in FEV1 or PEF to 60% to 80% of predicted values.

INPATIENT

Patients who warrant hospitalization require continued monitoring and systemic therapy. In general, the same treatments used in the emergency department are continued, with frequent reevaluation. Symptomatic improvement should be assessed and FEV1 or PEF measured one hour after administration of bronchodilator therapies. Improvement of more than 60% of predicted values or personal best is reassuring and should be a goal of treatment.

Therapy typically includes any combination of a SABA and short-acting muscarinic antagonist. Oxygen administration should maintain a saturation of 93% to 95% in adults and adolescents.11 Systemic corticosteroids should be administered. In cases of severe signs and symptoms, such as drowsiness, confusion, hypoxia, or absent breath sounds, the patient should be admitted to the intensive care unit and prepared for likely intubation. Some variables associated with an increased length of hospital stay include an elevated pulsus paradoxus, past intubation for asthma, and hospitalization for an asthma exacerbation in the past five years.40 Discharge criteria are similar to criteria for discharge from the emergency department.

POSTDISCHARGE CARE

Measures should be implemented before discharge to reduce the risk of rehospitalization for asthma exacerbations. Initiation of an ICS should occur before discharge, if not already prescribed. Patients on ICS therapy should be evaluated for the need for two to four weeks of step-up therapy and then reassessed. To ensure optimal outcomes, adherence and patient education should be addressed before discharge and on an ongoing basis. Adults should be discharged with oral corticosteroids at a dosage of 50 mg daily for five to seven days. Children should be treated with prednisolone, 1 mg per kg (up to 40 mg) daily for three to five days, which has been shown to be as effective as longer courses.41–43 Systemic corticosteroids have been shown to reduce hospitalizations, relapse of asthma symptoms, and use of SABAs.11,34,44

Close follow-up is recommended. During the follow-up visit, symptom control and risk of further exacerbations should be addressed. An asthma action plan should be reviewed, updated, or developed. All patients and caregivers should feel comfortable with the action plan, and a copy should be provided to schools or day care providers. Inhaler technique should be observed and adherence to medications assessed.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Pollart, et al.,10 and Higgins.45

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term acute asthma exacerbation. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and clinical trials. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports, Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and DynaMed were also searched. Whenever possible, if studies used race and/or gender as patient categories but did not define how these categories were assigned, they were not included in our final review. If studies that used these categories were determined to be essential and therefore included, limitations were explicitly stated in the manuscript. Search dates: November 18, 2021; November 4, 2022; January 9, 2023; May 23, 2023; and October 26, 2023.