Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(9):562-569

Author disclosure: Drs. Wipperman and Bragg have no financial affiliations. Dr. Litzner does not have a formal relationship with any commercial company to disclose, but a public database revealed food and beverage listings for several of the drugs mentioned in this article. None of these involved cash payments, and they are not considered a violation of our conflict-of-interest policy.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic folliculitis affecting intertriginous areas. Onset generally occurs in young adulthood to middle adulthood (18 to 39 years of age). Females and blacks are more than twice as likely to be affected. Additional risk factors include family history, smoking, and obesity. Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with several comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus and Crohn disease. The clinical presentation of hidradenitis suppurativa ranges from rare, mild inflammatory nodules to widespread abscesses, sinus tracts, and scarring. Quality of life is often affected, and patients should be screened for depression. Treatment includes wearing loose-fitting clothes, losing weight if overweight, and smoking cessation. Topical clindamycin alone can be effective for patients with mild disease. Patients with moderate disease can be treated with oral antibiotics, such as tetracyclines, in addition to topical clindamycin. Adalimumab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor, is effective for patients with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa. Surgical procedures are often necessary for definitive treatment and include local procedures, such as punch debridement and unroofing/deroofing. Wide excision is indicated for patients with severe, extensive disease and scarring.

Hidradenitis suppurativa, also known as acne inversa, is a chronic folliculitis that causes deep scarring and impacts quality of life.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence Rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking cessation and weight loss should be encouraged to decrease disease severity and improve response to treatment.3,4,11,12 | B | Consistent results from lower-quality cohort studies |

| Topical clindamycin and oral tetracycline antibiotics are effective for patients with mild to moderate hidradenitis suppurativa.15,19,27 | B | Evidence from limited-quality RCTs |

| Adalimumab (Humira) is effective for patients with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa.24,25,27 | A | Consistent evidence from high-quality RCTs |

| Wide excision is the definitive treatment for severe hidradenitis with extensive involvement and scarring.34,35 | B | Systematic review and meta-analysis of lower-quality clinical trials |

Epidemiology

The prevalence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States is approximately 0.1%, with increasing incidence over the past 10 years.1,2

Onset of hidradenitis suppurativa occurs in young adulthood to middle adulthood (18 to 39 years of age).1

Nonmodifiable risk factors include family history, female sex (incidence of 16.1 and 6.8 per 100,000 for females and males, respectively), and black race (incidence of 30.6 and 11.7 per 100,000 in blacks and whites, respectively).1

Modifiable risk factors include cigarette smoking and obesity.3,4

Hidradenitis suppurativa is associated with several systemic conditions, including diabetes mellitus and Crohn disease (Table 1).5,6

| Arthritis and spondyloarthropathy |

| Crohn disease |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Metabolic syndrome |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum |

| Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) |

Pathophysiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa is mediated by inflammatory and immunomodulatory factors affecting the folliculopilosebaceous unit in intertriginous areas with terminal hair and apocrine glands.

Increased cytokine and chemokine secretion results in hyperkeratosis, follicular occlusion, and cyst development.7,8

Eventual rupture of the folliculopilosebaceous unit triggers further inflammatory response leading to pain, abscess formation, and sinus tracts between lesions.

A cycle of scarring, fistulas, contractures, and systemic inflammation can occur.

Clinical Features

Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa present on a disease spectrum ranging from rare, mild inflammatory nodules to widespread abscesses, sinus tracts, and scarring. The disease can affect different parts of the body (Table 29).

Defining features include painful, deep-seated nodules (Figure 1) of varying size (0.5 to 2 cm) lasting days to months; abscesses (typically sterile) with malodorous, purulent drainage; open double “tombstone” comedones resulting from damage to the folliculopilosebaceous unit and loss of sebaceous glands (Figure 1 and Figure 2); interconnecting sinus tracts; scarring, fissures, and contractures in severe disease; and chronic, bilateral disease with a recurrent course.

| Areolae and inframammary areas |

| Axillae (most common) |

| Gluteal folds |

| Groin (prepuce/scrotum in males and mons pubis/labia minora in females) |

| Perianal area |

| Perineum |

DIAGNOSIS

Hidradenitis suppurativa is diagnosed clinically and usually can be differentiated from other conditions based on clinical presentation (Table 3).

On average, diagnosis is delayed seven years from symptom onset, possibly because of delays in seeking treatment or incorrect initial diagnoses.10

Bacterial cultures are not routinely indicated but can exclude primary or secondary infection if needed.

Skin biopsy can help differentiate hidradenitis suppurativa from other diagnoses, such as cutaneous Crohn disease in those with perianal involvement.

| Condition | Distinguishing features |

|---|---|

| Acne conglobata | Severe nodular acne on the back, chest, face, and neck; predominantly affects men |

| Cutaneous Crohn disease | Perianal lesions with extension of fistulous tracts past the dentate line |

| Granuloma inguinale | Genital ulcerations and subcutaneous granulomas |

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | Unilateral groin adenopathy; proctocolitis in men who have sex with men |

| Pilonidal cyst | Sacrococcygeal cyst or abscess; occurs more often in men |

| Primary bacterial abscess | No accompanying nodules, superficial rather than deep, nonchronic |

| Recurrent furunculosis | Absence of open comedones in inguinal areas |

STAGING

The Hurley classification system is used to define severity and guide treatment.

Stage I: single or multiple abscesses without sinus tracts or scarring

Stage II: abscess recurrence with sinus tracts and scarring; widely separated lesions

Stage III: diffuse skin involvement with multiple sinus tracts and widespread abscess formation

Treatment

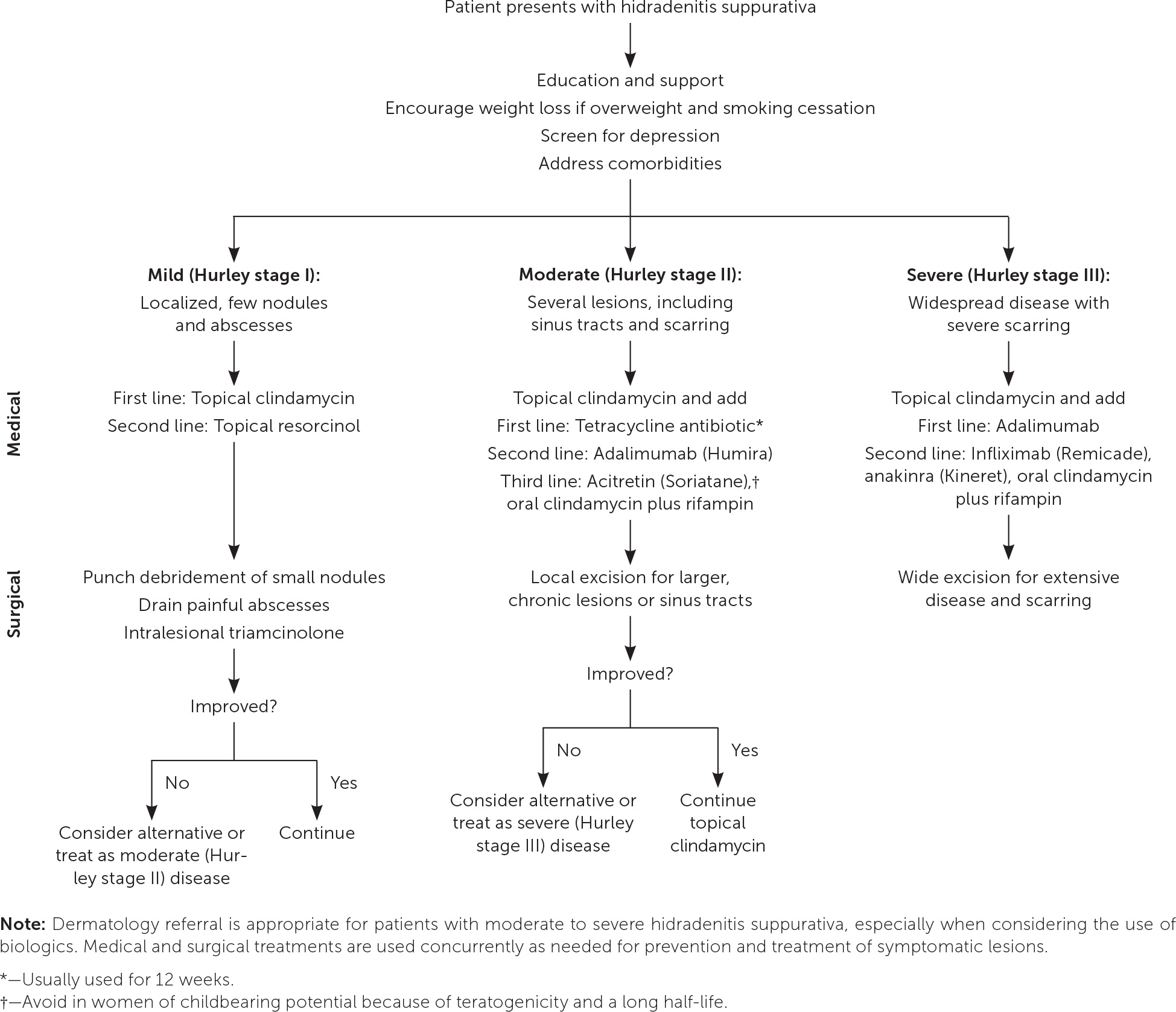

Figure 3 is an algorithm for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. The evidence for these treatments is mostly limited to observational studies with few high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

NONPHARMACOLOGIC

Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa should be counseled on ways to prevent worsening symptoms or flare-ups, including wearing loose-fitting clothes to prevent friction, although evidence for this is limited; weight loss if overweight; and smoking cessation. A 15% weight loss is associated with significant improvement in disease severity.11 Patients who smoke are twice as likely to develop hidradenitis suppurativa compared with nonsmokers, and smoking is associated with decreased response to treatment.3,12

Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa should be screened for associated conditions, including depression and diabetes mellitus, and these conditions should be appropriately addressed.

Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have lower disease-related quality of life compared with other chronic skin conditions. Pain, disfigurement, and odor can result in lower self-esteem, increased social isolation, and higher rates of anxiety and depression compared with the general population.13 The risk of suicide among patients with hidradenitis suppurativa is nearly 2.5 times that of the general population.14 Patients should be directed to support groups (see https://www.hs-foundation.org/support).

TOPICAL TREATMENTS

One small RCT (n = 30) demonstrated significant improvement in symptoms and abscess burden with topical clindamycin 1% applied directly to active lesions twice daily for 12 weeks.15 Topical clindamycin may be combined with systemic treatments.

Limited data suggest topical resorcinol 15% applied to painful nodules and abscesses once or twice daily as needed hastens resolution and improves pain, but it can cause skin irritation.16

Chlorhexidine (Peridex) and benzoyl peroxide washes are often recommended, although there are no studies examining their use for hidradenitis suppurativa.17

ORAL ANTIBIOTICS

Oral antibiotics may be more useful for their immunomodulatory rather than antimicrobial effects in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa.18

One small RCT (n = 46) of patients with mild to moderate hidradenitis suppurativa showed that tetracycline, 500 mg twice daily for three months, resulted in fewer abscesses and nodules but was not superior to topical clindamycin.19 Doxycycline, 100 mg once or twice daily, is an alternative.

Observational data suggest that combining clindamycin, 300 mg twice daily, and rifampin, 300 mg twice daily, for 10 to 12 weeks is effective. However, gastrointestina l adverse effects and drug-drug interactions limit the use of this treatment.20,21

HORMONAL THERAPIES

Female patients with cyclic flare-ups associated with menstruation may benefit from antiandrogenic therapies.22

In a retrospective study of 63 female patients, spironolactone, 25 to 200 mg daily, decreased inflammation and pain with no difference between smaller (less than 75 mg) and larger (more than 100 mg) doses.23

BIOLOGICS

Recent evidence supports the use of biologics for patients with moderate hidradenitis suppurativa that is not responsive to tetracycline antibiotics and for initial treatment of severe disease. Dermatology referral is appropriate for patients with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa, especially when considering the use of biologics.

TUMOR NECROSIS FACTOR ALPHA INHIBITORS

Adalimumab (Humira), which is given as a self-administered weekly subcutaneous injection, has the highest-quality evidence among the treatments for hidradenitis suppurativa. It is the only medication currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Two double-blind RCTs including more than 300 patients with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa found that those taking adalimumab had significant improvement compared with those taking placebo, with a number needed to treat of 3 to 6 for at least 50% improvement after 12 weeks of treatment.24 An open-label extension study found sustained response after three years of continued treatment.25

One small RCT (n = 38) found that infliximab (Remicade) is effective in improving pain, disease severity, and quality of life in patients with moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa.26 Infliximab is given as an intravenous infusion.

Etanercept (Enbrel) is not effective for hidradenitis suppurativa.27

Adverse effects of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors include serious infection (predominantly mycobacteria), neutropenia, autoimmune conditions, heart failure, and lymphoma.

INTERLEUKIN-1 RECEPTOR ANTAGONISTS

One small RCT (n = 20) found that anakinra (Kineret) is an effective treatment for moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa, including a prolonged time to new exacerbation after cessation of the medication.28 Anakinra is given as a daily subcutaneous injection that is self administered.

OTHER

In a case series of 36 patients with acute nodules or abscesses smaller than 2 cm, treatment with triamcinolone, 10 mg per mL (average dose was 0.75 mL) injected into the lesion, demonstrated a significant reduction in pain after one day and signs of inflammation within one week.29

Apremilast (Otezla) is an oral phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor that inhibits inflammatory response. A placebo-controlled RCT (n = 20) found a number needed to treat of 2 for at least 50% improvement after 16 weeks of apremilast therapy, and the medication was well tolerated.30

A case series of 23 patients with mild hidradenitis suppurativa treated with metformin for six months showed improvement in disease severity and quality of life.31

Acitretin (Soriatane) and isotretinoin are oral retinoids occasionally used to treat hidradenitis suppurativa based on limited evidence.32

SURGICAL TREATMENT

The goal of surgical procedures in the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa is to control inflammation by removing the diseased folliculopilosebaceous unit, sinus tracts, and associated debris to prevent further progression and scarring. Local procedures include punch debridement, unroofing/deroofing, skin-tissue sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling, and laser excision (Table 433).

Incision and drainage may be necessary for acutely inflamed, painful abscesses but should not be routinely performed, because it does not remove the folliculopilosebaceous unit and lesions usually recur.34 Punch debridement is preferred, because it relieves pain and removes the folliculopilosebaceous unit.

Local excisional procedures should heal by secondary intention, because primary closure is associated with higher recurrence rates.35

In a prospective within-patient controlled trial of 22 patients with symmetrical, moderate hidradenitis suppurativa, one affected side was treated with four monthly sessions of neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd: YAG) laser therapy plus topical benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin daily, and the other affected side of the same patient was treated with topical benzoyl peroxide and clindamycin alone. The side treated with Nd:YAG laser therapy showed 73% greater improvement on a clinical severity scale compared with a 23% greater improvement on the side not treated with Nd:YAG laser therapy.36

Carbon-dioxide laser excision may help patients with more extensive involvement and has high patient satisfaction; however, it has been studied only in patients with Hurley stage II disease and has higher recurrence rates compared with wide excision.37

Local excision has fewer complications, such as infection, delayed healing, scarring, and contracture formation, compared with wide excision but has higher recurrence rates.35 Wide excision is the definitive treatment for patients with extensive involvement and scarring.34,35

Combining biologic agents with surgical treatment is associated with decreased recurrence compared with surgery alone.38,39

| Procedure | Indication | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Punch debridement (“mini-unroofing”) | Acutely inflamed, small nodules and abscesses | 5- to 8-mm punch biopsy at the center of the lesion removes the folliculopilosebaceous unit; debridement with manual expression and gauze curettage removes any underlying inflammatory exudate; healed by secondary intention |

| Nd:YAG laser therapy | Chronic abscesses, nodules, and sinus tracts | Laser treatment of affected areas that is directed at destroying hair follicles in the superficial and mid-dermis; may be combined with carbon-dioxide laser therapy; healed by secondary intention |

| Unroofing/deroofing | Chronic abscesses, nodules, and sinus tracts | Overlying “roof” of the lesions is excised and underlying cavities exposed with sharp scissors, carbon-dioxide laser, or electrosurgery and curetted until normal underlying tissue remains; healed by secondary intention |

| Skin-tissue sparing excision with electrosurgical peeling | Chronic abscesses, nodules, and sinus tracts | Subsequent tangential transections remove diseased skin while preserving as much normal skin as possible; healed by secondary intention |

| Wide excision | Extensive disease and scarring | Entire area of involved skin with margins extending beyond the affected area is excised; healed by secondary intention; local flaps or skin grafting may be needed depending on size and location |

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term hidradenitis suppurativa. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and systematic reviews. Also searched were the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, DynaMed, http://choosingwisely.org , and UpToDate. Search dates: October 1 to December 20, 2018, and July 21, 2019.