Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(10):628-635

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Academic underachievement, such as failing a class and the threat of being held back because of academic issues, is common. Family physicians can provide support and guidance for families as they approach their child's unique academic challenges. Specific learning disabilities are a group of learning disorders (e.g., dyscalculia, dysgraphia, dyslexia) that impede a child's ability to learn. Understanding standard educational terms; looking for medical, family, and social risk factors associated with academic underachievement; and investigating the medical differential for academic underachievement can help direct the family to appropriate care. The physician can provide medical documentation to support an individualized education program evaluation and address risk factors that schools may not be aware of or cannot assess. The family physician can support children and families by understanding the connection between risk factors, medical and educational evaluations, and educational resources.

Many school-aged children experience academic underachievement by not being able to maintain average grades, failing a single class, performing below their grade level in one or more subjects, or receiving below-average scores on state or classroom tests. The number of public school students in the United States who receive special education support increased from 8.3% in 1976 to 1977 to 13.8% in 2004 to 2005. A large portion of the overall increase is attributed to the number of students who are now eligible for services because of a specific learning disability (currently 4.6% or 2.3 million persons).1 This article outlines an approach to the evaluation of academic underachievement with a focus on specific learning disabilities.

Specific Learning Disabilities

Specific learning disabilities are a group of disorders that impede a child's ability to learn and include dyscalculia, dysgraphia, and dyslexia. The overall prevalence of specific learning disabilities for children in the general population is 4% to 9%.2 A specific learning disability is not considered an intellectual disability.2 Many medical and psychosocial conditions should be considered risk factors for specific learning disabilities(Table 1).2–20 Medical conditions that can result in learning problems with similar features or symptoms as a specific learning disability, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), are listed in Table 23,5,9,10,12–16,21–25 and Table 3.3,4,11,13,17,21,23,24,26–28 Some of these conditions, such as visual impairment, can be ameliorated, which can resolve the associated learning problem. Early identification of the specific learning disability and treatment that begins by the third grade at the latest lead to the best outcomes.29 Later identification has a poorer prognosis, such as an ongoing failure to achieve grade-level standards and subject fluency. The primary intervention for a specific learning disability is academic based around the child's specific needs with special education supports that can be used with individualized, targeted medical support.

This article focuses on the physician working with the family to obtain appropriate medical and educational evaluations. Physicians can investigate risk factors and comorbidities, and help families work with the school to determine appropriate educational supports.

| Family history |

| Specific learning disability3–5 |

| Special education services or educational supports2,6 |

| Level of parental education6 |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder or attention diagnosis3,7 |

| Not reading for pleasure8 |

| Neurocutaneous disorder or other genetic disorders9 |

| Medical |

| Premature birth10 |

| Low or very low birth weight10,11 |

| In utero substance exposure (e.g., tobacco, alcohol)12–14 |

| Medical conditions (e.g., recurrent otitis media, asthma)3 |

| Genetic syndromes or metabolic disorders5,15,16 |

| Early speech-language delay17 |

| Neurologic conditions or insults (e.g., traumatic brain injury, seizures)3,9,16 |

| Social |

| Poverty8 |

| Cultural considerations or environmental disadvantage11,18 |

| Domestic violence or unsafe home environment (e.g., parental substance abuse)18 |

| Adverse childhood experiences19 |

| Lack of adequate instruction20 |

| Developmental delays* (global developmental and specific delays)3,13,21,22 |

| Genetic syndromes or metabolic disorders5,15,16 |

| Hearing impairment*23 |

| In utero substance exposure12–14 |

| Intellectual disability (formerly mental retardation)3,10,21,22 |

| Neurocutaneous disorders (e.g., neurofibromatosis, Sturge-Weber syndrome, tuberous sclerosis)9 |

| Neurologic conditions or insults (e.g., traumatic brain injury, seizures)9,16 |

| Seizure disorder (e.g., absence, partial, partial-complex)3 |

| Sleep disorders24 |

| Visual impairment*25 |

| Anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder)23 |

| Behavioral disorders (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder)11,26 |

| Bullying27 |

| Depressive disorders (e.g., major depressive disorder)23,26 |

| Headaches3,24 |

| Motor delays or disorders26 |

| Neurodevelopmental disabilities (e.g., attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder)11,23,26 |

| Second specific learning disability4 |

| Social-emotional problems (e.g., social skill deficits)11 |

| Speech-language delays or disorders3,13,17,21 |

| Substance abuse28 |

School Evaluations

INITIAL EVALUATION

Physicians should be aware of standard terms used in public education law that allow for better communication with schools (Table 4).20,22,30–33 Schools in many states use a response-to-intervention protocol as an early intervention for school underachievement and identification of children with specific learning disabilities before beginning an evaluation for special education services.20,31,32 The goal of a response to intervention is to decrease the number of children automatically evaluated for special education services by giving additional support to all underachieving children through a tiered academic support program in general education. Children with more intensive needs move through minimal, moderate, and maximal supports. Families do not have to wait until a response to intervention is completed to request an individualized education program (IEP) evaluation; however, many families are unaware of their child's enrollment in response-to-intervention supports.34

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Section 504 plan (part of the Americans with Disabilities Act) | Provides accommodations for general education students with disabilities to ensure equal access to the standard curriculum; physician support can help obtain a 504 plan for a child who does not qualify for an IEP but has any issue that inhibits learning |

| Education, general | Programs provided or available to all children |

| Education, special | Individual instruction and related services to meet the unique needs of eligible children |

| Free appropriate public education | Free education programming that meets the needs of the learner in the public school is a right of all children under federal law |

| IEP | Document delineating special education services for an eligible child required by state or federal laws; created by a multidisciplinary team, discussed during a conference; the child must be found eligible on psychoeducational evaluation by demonstrating a need for specialized instruction in one of 13 categories to receive services |

| Individuals with Disabilities Education Act | A federal law that provides educational services for children with disabilities |

| Least restrictive environment | Children with disabilities are educated, as much as possible, in the general education setting |

| Psychoeducational testing or evaluation | Means of assessing a child's strengths or weaknesses based on the child's classroom and educational needs |

| Response to intervention | Program to prevent children from falling behind academically using three-tier educational services (e.g., whole class, small group, intensive intervention); failure to adequately progress in tier 3 leads to an IEP assessment20,31,32 |

| Specific learning disability | Academic challenges in a subject area compared with peers despite appropriate instruction; separate from cognitive disability or intellectual disability; includes a variety of learning difficulties with eligibility determined through psychoeducational assessment; treated with modified educational programming; dyslexia is served under the specific learning disability eligibility33 |

ELIGIBILITY DETERMINATION

Following a response to intervention or if there is a significant lack of progress moving through the three tiers of the response to intervention, the school may evaluate the child for an IEP. Schools determine eligibility for special education services based on the needs of the student that are impacting academic work.21,22,30 This process is unlike making a medical diagnosis, which is based on the presence of specific symptoms meeting diagnostic criteria35 (e.g., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.). The following outcomes for children with academic underachievement who have been assessed by a school and a physician are possible.

Medical Diagnosis and School Eligibility. A child is found to have a cognitive disability that is causing academic difficulties in school. The physician diagnoses the child with an intellectual disability.

Medical Diagnosis Only. The physician diagnoses the child with a mild visual impairment, which is corrected with prescription glasses.

School Eligibility Only. The school determines the child is eligible for special education services under the category of specific learning disability. In most cases, students do not receive medical treatment for a specific learning disability; as such, a medical diagnosis may be unnecessary.

Schools provide educational evaluations using a multidisciplinary team approach that is based on concerns from school staff, such as poor academic performance, when determining special education eligibility.22 Schools may have a differential with several eligibility categories for academic underachievement depending on the child's challenges in school. The differential can include a specific learning disability, cognitive disability (i.e., intellectual disability), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), developmental delay, or other health impairment.1,22,30

A child who qualifies for an IEP is found eligible under a primary eligibility category designation. A secondary category may also be found. Some categories may be used simultaneously (e.g., specific learning disability with ASD, intellectual disability with ASD), whereas others are mutually exclusive (e.g., specific learning disability, intellectual disability). The “other health impairment” category can be confusing and may be appropriate for a variety of medical diagnoses (e.g., ADHD, epilepsy, asthma) that cause absenteeism, result in impaired attention (e.g., cognitive slowing because of certain antiepileptic medications), or inhibit the child's ability to perform in the classroom in other ways.

Medical Evaluations

EVALUATION OF A CHILD WITH A POTENTIAL LEARNING DISABILITY

Physicians can watch for several early risk factors for specific learning disabilities before academic underachievement starts.36 They are often the first people that families approach with academic problems in the school setting. These concerns should prompt the physician to evaluate the child for issues with learning. If a child presents with behavior problems at school, the physician should also ask about academic underachievement because early academic underachievement or failure may be the cause or a significant contributor to the development of challenging behaviors.11,21

The family physician plays a vital role in medical evaluation, coordination, interdisciplinary communication, and generalized support for the family and school after the academic or school behavior problems have been identified.35

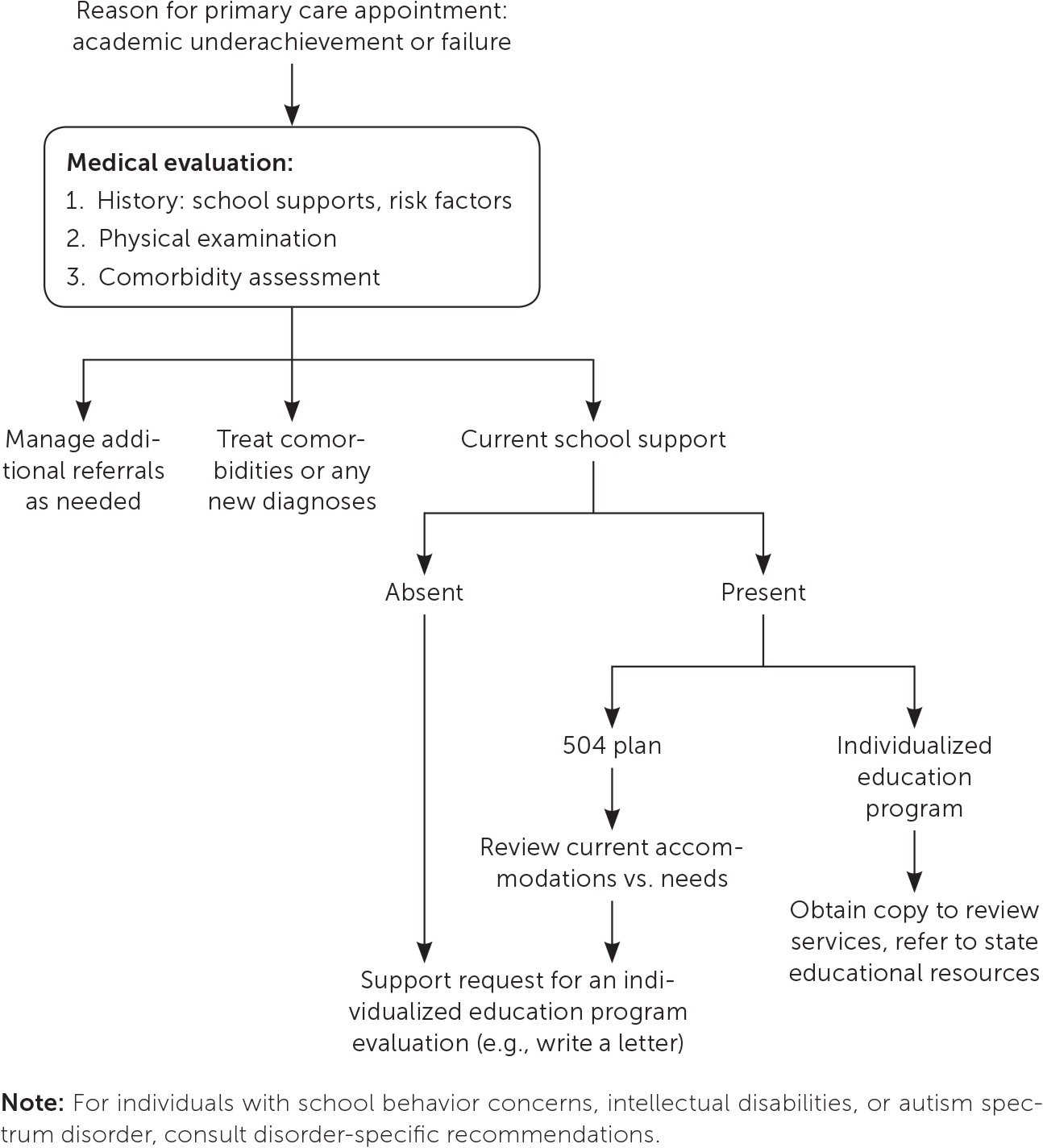

Figure 1 outlines an approach to the first appointment with a child who is underachieving or who has an academic failure concern.

A medical examination should involve a detailed history, including a review of medical risk factors (e.g., premature birth, very low birth weight; Table 12–20) and current comorbidities (e.g., speech-language delay or disorder; Table 33,4,11,13,17,21,23,24,26–28 ) that are associated with specific learning disabilities.The evaluation should also include appropriate parent- and child-completed screening based on age (e.g., annual adolescent depression screening according to the American Academy of Pediatrics37 and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force38), chart review, and hearing and vision assessment if not recently assessed.23,25 The physician should be attentive to relevant physical examination findings (e.g., head circumference, birthmarks, facial morphology; Table 5). Most importantly, the physician should consider key differential items that may contribute to academic underachievement or where treatment within the medical field (e.g., cognitive behavior therapy, antiepileptic medication) will help with educational needs (Table 2).3,5,9,10,12–16,21–25 Table 6 lists symptom identification and screening resources for specific learning disabilities.

| Dermatologic | |

| Birthmarks: focus on neurocutaneous findings such as café au lait macules, axillary or inguinal freckling, shagreen patches, portwine stains | |

| Sacral pit or dimple | |

| Dysmorphology | |

| Digit morphology | |

| Facial morphology (e.g., fetal alcohol syndrome) | |

| Other abnormalities (e.g., pectus excavatum) | |

| General neurologic | |

| Cranial nerve examination: focus on pupillary reflex, eye, and facial movements | |

| Mental status examination, including speech and conversation | |

| Motor function and balance: focus on gait, tone, limb, and movement symmetry | |

| Reflexes | |

| Growth parameters | |

| Head circumference measurement: plot with tools such as the World Health Organization charts for boys and girls; microcephaly is always a cause for concern | |

| Height and weight | |

| Handwriting | |

| Handedness | |

| Spelling, spacing, legibility of letters | |

| Sensorium | |

| Hearing screening | |

| Vision screening |

| Resource | Website |

|---|---|

| Mental health | |

| ProjectTEACH rating scale library | https://projectteachny.org/rating-scales/ |

| Child Mind Institute Symptom Checker | https://childmind.org/symptomchecker/ |

| American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Mental Health Screening and Assessment Tools for Primary Care | https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Mental-Health/Documents/MH_ScreeningChart.pdf |

| Development | |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Developmental Milestones (includes a downloadable milestones app) | https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html |

| AAP Screening Technical Assistance & Resource Center (young children only) | https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Screening/Pages/default.aspx |

| Combination | |

| University of Washington Medicine and Seattle Children's Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics Screening & Surveillance | https://depts.washington.edu/dbpeds/Screening%20Tools/ScreeningTools.html |

Children with neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., ASD) may not be able to participate in office-based screenings fully and might require an evaluation by a subspecialty office (e.g., audiology) to complete otherwise routine testing. Children with more complicated medical disorders (e.g., seizures) or concerning risk factors (e.g., family history of neurofibromatosis) may need to be treated by pediatric subspecialists. This would include children with phenylketonuria who have academic underachievement when phenylalanine levels are high and require ongoing subspecialty treatment through metabolic genetics or pediatric neurology.

For parents who are concerned that their child may have a specific learning disability, there are two main options for evaluation22,30: a public school team evaluation or an external evaluation with a nonschool psychologist. The school district may not accept the information produced by an external psychological evaluation. Insurance companies often do not pay for psychological evaluations for purely educational reasons; therefore, external evaluations for specific learning disabilities are often self-pay, which should be discussed before referring families to a nonschool psychology evaluation for a specific learning disability.

The physician can assist families by writing a school evaluation letter of support to introduce open communication between the family, the physician, and the school when an evaluation has not yet been initiated or when information was missing from a previous evaluation.30,35 Many family support websites provide example letters for reference (Table 7). The physician can alternatively produce a summary of identified medical needs or medical evaluation steps to be shared with the school to support the family's evaluation request and school determination of eligibility. When writing a medical summary letter, the physician should again identify and describe the child's known medical needs that may impact the academic setting and any ongoing or intended medical evaluation.22,30,35 The information is used by the school as a component of assessment and to develop the overall education evaluation and plan at school.22

| Organization | Website | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Center for Parent Information & Resources | https://www.parentcenterhub.org/ | Information about state-based parent resource centers |

| Individuals with Disabilities Education Act | https://sites.ed.gov/idea/parents-families/ | Family legal rights |

| Learning Disabilities Association of America | https://ldaamerica.org/ | Support for parents |

| National Center for Learning Disabilities | https://www.ncld.org/ | Leaders advocating for equal rights and opportunities |

| Response to Intervention Action Network | http://www.rtinetwork.org/ | Targets educators; provides information about response to intervention methods, supports, and benefits |

| State Departments of Education | State specific | Information for parents and educators about state laws and practices |

| Understood | https://www.understood.org/en (English) https://www.understood.org/es-mx (Spanish) | Targets parents; provides support around learning and attention issues |

EVALUATION OF A CHILD WITH A SCHOOL EVALUATION IN PROGRESS

The physician should perform a medical assessment that includes a detailed history, a review of medical risk factors, a physical examination, and the identification of underlying and contributory medical conditions. The evaluation should also include appropriate parent- and child-completed screening based on age and needs. When requested by the parents or school with a family-signed release of information, the physician can provide medical documentation that supports evaluation and IEP planning or addresses risk factors3,10,11,17 that schools may not be aware of or cannot assess. A standard release-of-information form is adequate for school communication.

A medical summary letter can be solicited directly by the school or family when a medical evaluation is already in process. Medical information is a requirement for some eligibilities (e.g., other health impairment) and a school evaluation and special education services will not proceed without this.

Some children with learning and attention needs may not qualify for an IEP based on the school's criteria under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; however, they may receive lower intensity accommodations through the use of a 504 plan,30 such as preferential seating or a supplemental note set.

CHILDREN WITH AN IEP

For children who already have an IEP but whose parents are concerned about academic underachievement, the physician should request a copy to review key elements, focusing on eligibility category, current special education services, and the educational setting.35

IEP information is essential because the IEP communicates t he school 's current understanding of the child's needs, which may or may not align with what is known in the medical record about the child's physical, psychological, and developmental needs. The physician can help families understand why and what the child currently receives as school supports, incorporate school information into the medical plan as appropriate, or share relevant medical information back to the school. School eligibility does not automatically transfer from the school to the medical setting; therefore, reviewing the IEP allows the medical chart to be updated. The responsibility of performing any appropriate medical evaluation is up to the physician. Additionally, as children grow, academic and medical needs often change as the disorder is treated, requiring ongoing, individualized medical care.

The physician can share educational resources related to special education law and classroom supports for their state with families (Table 7). If the family has IEP questions, this information will give them a reference point for exploration. Many states have advocacy groups that work directly with families to interface with schools in pursuing IEP changes or further evaluation.

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key terms learning disability, specific learning disability, learning disorder, and dyslexia, with modifiers including reading, medical problems, risk factors, and differential diagnosis. The search included meta-analyses and reviews. A Medline search was completed using the key terms learning disability, specific learning disability, learning disorder, and dyslexia, with modifiers including comorbidities, differential diagnosis, risk factors, medical evaluation with developmental disabilities/alcohol-related disorders/adolescent, prenatal exposures, in utero exposures, neurocutaneous syndromes, genetic diseases, genetic syndromes, metabolic disease, metabolic syndromes, nutrition disorders, malnutrition, brain disease metabolic, and congenital, hereditary, and neonatal diseases and abnormalities. A Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews search was completed using the key terms learning disability, specific learning disability, learning disorder, dyslexia, academic underachievement, and academic success. Search dates: January 2 and August 16, 2019.