Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(2):89-94

Related letter: Importance of Appropriate Diagnosis Before Prescribing Corticosteroids

Published online December 16, 2019.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

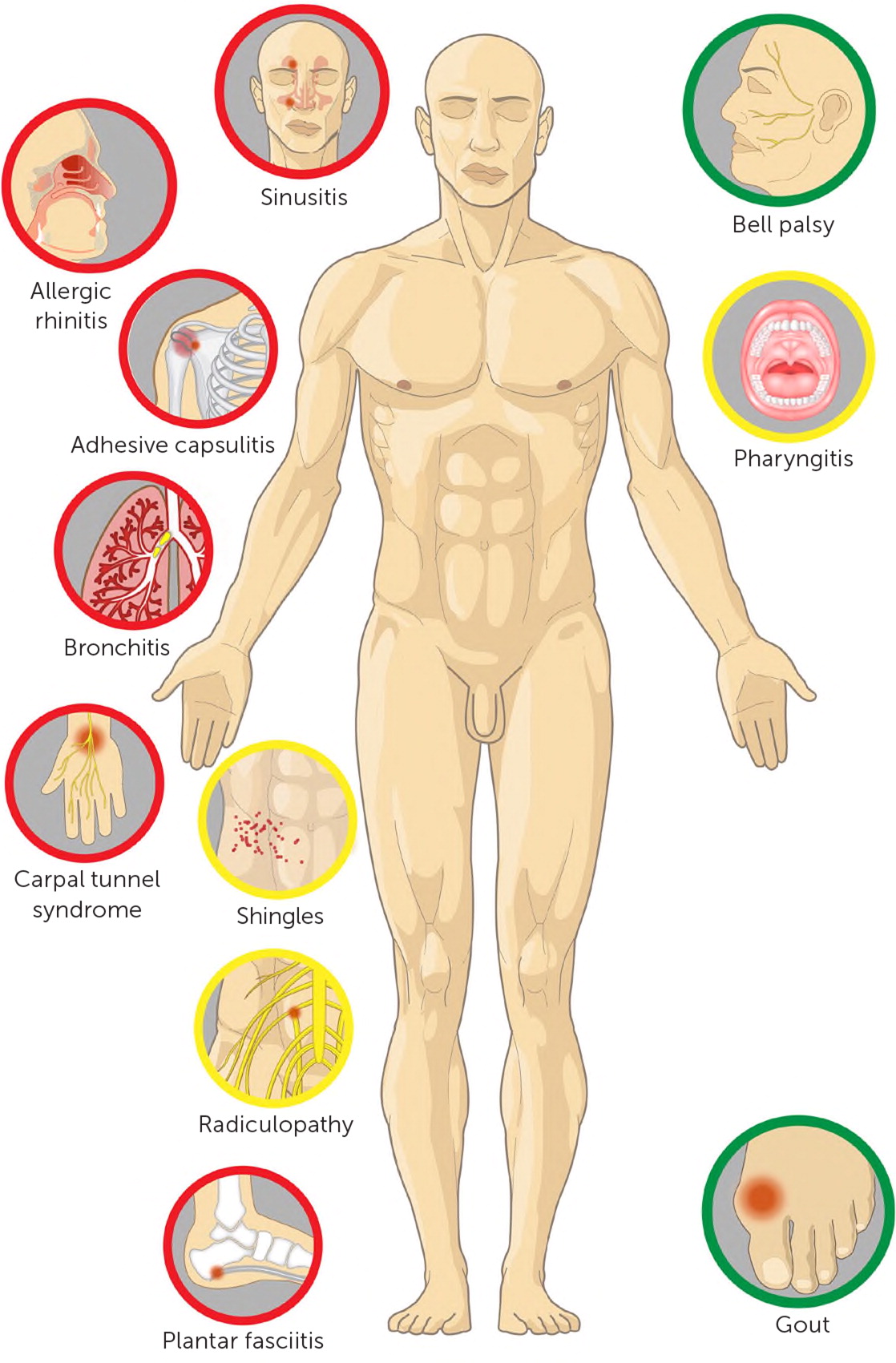

Short-term systemic corticosteroids, also known as steroids, are frequently prescribed for adults in the outpatient setting by primary care physicians. There is a lack of supporting evidence for most diagnoses for which steroids are prescribed, and there is evidence against steroid use for patients with acute bronchitis, acute sinusitis, carpal tunnel, and allergic rhinitis. There is insufficient evidence supporting routine use of steroids for patients with acute pharyngitis, lumbar radiculopathy, and herpes zoster. There is evidence supporting use of short-term steroids for Bell palsy and acute gout. Physicians might assume that short-term steroids are harmless and free from the widely known long-term effects of steroids; however, even short courses of systemic corticosteroids are associated with many possible adverse effects, including hyperglycemia, elevated blood pressure, mood and sleep disturbance, sepsis, fracture, and venous thromboembolism. This review considers the evidence for short-term steroid use for common conditions seen by primary care physicians.

An analysis of national claims data found that 21% of adults received at least one outpatient prescription for a short-term (less than 30 days) systemic corticosteroid over a three-year period, even after excluding patients who had asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cancer, or inflammatory conditions for which chronic steroids may be indicated. The most common diagnoses associated with outpatient prescribing of short-term corticosteroids included (from most frequent to least frequent) upper respiratory infection, spine conditions, allergic rhinitis, acute bronchitis, connective tissue and joint disorders, asthma, and skin disorders.1 Most of these short courses of corticosteroids were prescribed by family medicine and internal medicine physicians.1 Several recent studies have confirmed high rates of prescribing systemic corticosteroids for patients with acute respiratory tract infections, ranging from 11% of all outpatient respiratory infections in a national study 2 to 70% of patients with at least one week of cough in a small study at two urgent care clinics.3 Prescribing oral corticosteroids in short courses may seem to be free from significant adverse effects; however, a large national data set of private insurance claims, which included approximately 1.5 million people, showed that a short course of oral steroids was associated with an increased risk of sepsis (relative risk [RR] = 5.3), venous thromboembolism (RR = 3.3), and fracture (RR = 1.9) in the five to 30 days after steroid initiation compared with those who had not received a short course of steroids.1 The estimated number needed to harm after a short course of steroids was 140 for fracture, 454 for venous thromboembolism, and 1,250 for sepsis. There are also case reports of avascular necrosis developing after even one course of systemic steroids.4,5 It is well understood that short-term systemic steroids can cause hyperglycemia, elevated blood pressure, immunocompromised state, mood and sleep disturbance, and fat necrosis when injected. This review summarizes the evidence base for the effectiveness of short-term systemic (either oral or injected intramuscularly) steroid use in adults in the outpatient primary care setting (Figure 1). This review does not address the role of systemic corticosteroids for conditions where there is a clear consensus supporting effectiveness, such as for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. This review also does not address localized steroid use, as with joint injection, and topical and inhaled formulations.

Acute Bronchitis

Short-term systemic corticosteroids are often prescribed for patients with acute bronchitis.1–3 This may be appropriate for bronchitis associated with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; however, it is not appropriate for most other patients with acute bronchitis. The Oral Steroids for Acute Cough trial was a multicenter, randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 401 adults with acute cough,6 including approximately one-third with audible wheeze at baseline; patients who had asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease were excluded. Patients were randomly prescribed prednisolone (40 mg once daily) or placebo for five days and followed for up to 28 days. There was no improvement on any clinical parameters, including the duration of cough, severity of cough, use of medications, or patient satisfaction.6 Approximately 40% had a peak flow rate less than 80% of predicted at study entry, but even in this subgroup, those receiving corticosteroids had no greater improvement in any outcomes compared with placebo, including duration of abnormal peak flow.6 This study's strengths include patient selection, recruitment from primary care setting, blinding, and patient-centered outcomes.6

Acute Pharyngitis

Short-term systemic corticosteroids may provide some benefit for patients with peritonsillar abscess7 or severe sore throat.8 A meta-analysis concluded that there was a small benefit in children with sore throat; however, this analysis included studies that covered a range of severity, that were generally small, and that were at high risk of bias.9 The most rigorous study evaluating the effectiveness of systemic corticosteroids for nonsevere sore throat comes from a large RCT of 565 adults in the primary care setting with mild to moderate sore throat.10 The adults were randomized to receive one dose of oral dexamethasone (10 mg) or placebo. The primary outcome—the proportion of patients with resolution of symptoms at 24 hours—was not found to be different between treatment groups. Thus, steroid use for adults with mild to moderate pharyngitis is not supported by evidence.

Acute Sinusitis

Regarding treatment of clinically diagnosed acute sinusitis, a Cochrane review identified five randomized trials comparing a corticosteroid to placebo.11 In one trial, no benefit was seen when the steroid was used as monotherapy. The other four trials compared antibiotic plus steroid with neither and found greater symptom resolution or improvement at 3 to 7 days in the active therapy group (72.4% vs. 54.4%). Most patients were seen by an otolaryngologist and had symptoms less than 10 days.11 It is not possible to know what specific role steroids may have had beyond antibiotics in the included trials. A Cochrane review examining short-term oral steroids for chronic sinusitis does not show sufficient evidence to support its routine use.12

Allergic Rhinitis

One study compared the effectiveness of oral and intranasal steroids for allergic rhinitis and found no difference between the two routes of administration.13 Current allergy society guidelines do not recommend systemic corticosteroids for the treatment of allergic rhinitis, especially because nasal steroids are effective for this condition and do not have systemic side effects.14,15 Before the wide adoption of nasal steroid use, a group in Denmark found a higher rate of diabetes mellitus and osteoporosis in patients who had received repeated steroid intramuscular systemic injections (at least one injection per year for at least three years) for allergic rhinitis compared with those who received allergy immunotherapy.16 In summary, a short course of systemic steroids is not recommended for allergic rhinitis.

Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Short-term systemic steroids have not been studied in RCTs for allergic contact dermatitis, including poison ivy and poison oak.17 However, expert opinion recommends systemic corticosteroids for allergic contact dermatitis involving more than 20% of body surface area or significant reactions involving the face, hands, feet, or genitalia (locations where strong topical corticosteroids may be contraindicated). Concern has been raised that too short of a course (one week or less) can cause rebound for poison ivy; expert opinion recommends a 14-day course.17

Lumbar Radiculopathy

A systematic review of three studies with 171 patients found no significant pain difference two weeks after randomization with systemic steroids (mean difference in pain scale −1.8, [95% CI, −11.1 to 7.5]; P = 0.71).18 However, patients receiving steroids had more adverse effects, including epigastric symptoms, mood changes, and hyperglycemia.18 After that systematic review, an RCT identified 269 patients with acute lumbar radiculopathy attributable to a herniated disk; the patients were randomly prescribed prednisone (tapering from 60 mg to 20 mg daily over 15 days) or placebo.19 There were mixed results regarding possible benefit for the corticosteroid group vs. placebo. Three weeks after randomization, there was a small statistically significant, but not clinically significant, improvement in a disability index score (the predefined clinically significant outcome for disability index was set at a 7/100-point improvement, and the steroid group showed a 6.4/100-point improvement in disability index) and no difference in pain, with similar results at one year. No significant improvement occurred in the rate of those who eventually underwent spine surgery at one-year follow-up. One important limitation of this steroid trial is difficulty with blinding: At three weeks, significantly more patients in the prednisone vs. placebo group believed they had received the active drug (75% vs. 53%). In summary, in this study a 15-day course of steroids improved functional symptoms but not pain.19 Given the lack of consistent supporting evidence, short-term systemic corticosteroids should not be routinely offered for patients with lumbar radiculopathy. To date, there is no high-quality evidence evaluating the use of systemic steroids for cervical radiculopathy or for patients with nonradicular, noncancer-related back or neck pain.

Acute Gout

Short-term systemic corticosteroids for acute gout have not been evaluated in placebo-controlled trials,20 but they have been shown to have similar effectiveness as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. A study was performed for 416 patients presenting to an emergency department in Hong Kong who were clinically diagnosed with gout (nearly three-fourths of those enrolled had recurrent gout; joint aspiration was not required).21 Patients were randomized to take 50 mg of indomethacin three times daily for five days or to take 30 mg of prednisolone daily. The results showed equivalence of pain control at rest and with activity for the study's 14 days of follow-up. No serious adverse effects occurred in either group, but nausea and vomiting were significantly more common in patients who were prescribed indomethacin, whereas skin rash was more common in patients who were prescribed prednisolone. Similar findings were seen in a smaller primary care study comparing prednisolone and naproxen.22 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and steroids are equivalent treatments when treating gout. When a septic joint has been reasonably excluded, physicians can confidently prescribe corticosteroids for patients with acute gout.

Tendinitis/Periarticular Syndromes

In general, short-term systemic steroids have not been well studied for the treatment of most tendinopathy and/or periarticular syndromes, including plantar fasciitis, rotator cuff, elbow, and patellar tendinopathy syndromes. Systemic steroid use has been studied in patients with adhesive capsulitis.23 A recent systematic review and network meta-analysis show support for intra-articular corticosteroid therapy but not for systemic oral therapy.23

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

A systematic review and meta-analysis for carpal tunnel syndrome showed possible evidence after two to four weeks that oral short-term steroids are more effective than placebo, but there was no evidence of effectiveness beyond four weeks.24 In this review, only studies that excluded patients with systemic diseases were included. A study not included in this analysis (the study did not exclude patients with systemic diseases) included 77 patients, with a mean age of 49, randomly assigned to take oral steroids or to receive acupuncture.25 No difference was found between the two groups at two and four weeks, although the acupuncture group showed significantly improved results at seven and 13 months. The acupuncture group had a significantly better improvement in the global symptom score (ascertaining patient-reported pain, numbness, tingling, weakness or clumsiness, and nocturnal awakening), distal motor latencies, and distal sensory latencies when compared with the steroid group throughout the one-year follow-up period.25 There is moderate evidence that corticosteroid injections are more effective than oral steroids in the short term (after eight weeks).26 Taken together, oral steroids should not be viewed as the first-line treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome.

Bell Palsy

Two large well-designed RCTs with 551 and 829 patients, respectively, showed effectiveness of a 10-day oral prednisolone course for Bell/facial nerve palsy.27,28 Current guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation recommend short-term oral steroids for idiopathic facial nerve palsy within three days of symptom onset.29

Herpes Zoster

Two RCTs from the 1990s studied the effectiveness of systemic steroids for herpes zoster. Both studies randomized patients to acyclovir with or without a 21-day taper of corticosteroids. The studies excluded patients with hypertension, diabetes, or cancer. After randomization, patients had a median age of 61. The first trial randomized 208 patients to receive acyclovir with prednisone or placebo,30 whereas the second trial randomized 400 patients to receive acyclovir with prednisolone or placebo.31 In both studies, healing of rash, acute pain, and development of postherpetic neuralgia were assessed. In one study, prednisone did not help decrease time for rash healing, but it did help decrease acute pain level at one month.30 In the other study, prednisolone may have helped with rash healing and acute pain at seven and 14 days but not beyond.31 Neither study showed that steroids decreased the risk for postherpetic neuralgia.32 Adverse effects of corticosteroids were reported, including gastrointestinal symptoms, and edema. Corticosteroids could potentially increase the risk of secondary bacterial skin infection, which is a possible complication of herpes zoster.33,34 Steroids should not be used without antivirals, may help decrease acute pain for zoster when used concomitantly with antivirals, and do not reduce the incidence of postherpetic neuralgia. Research is needed to determine whether there is a role for steroid use after antiviral therapy in those with recalcitrant symptoms. Given the lack of clear effectiveness for steroids and possible adverse effects, routine steroid use for zoster is not supported by evidence.

Data Sources: A Medline search was completed using the key terms corticosteroids and each of the specific diagnoses reviewed (acute pharyngitis, acute sinusitis, acute bronchitis, lumbar radiculopathy, cervical radiculopathy, allergic rhinitis, allergic contact dermatitis, acute gout, carpal tunnel syndrome, Bell's palsy, herpes zoster, shingles, tennis elbow, adhesive capsulitis, frozen shoulder, rotator cuff tendinitis, and plantar fasciitis). The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and UpToDate were also searched. Search dates: December 8, 2018, and September 20, 2019.

Editor's Note: Dr. Ebell is deputy editor for Evidence-Based Medicine for AFP.