Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(4):221-228

Patient information: See related handout on valley fever, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis (valley fever) is caused by inhaling airborne spores of the fungus Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii. Residing in or traveling to areas endemic for Coccidioides is required for the diagnosis; no person-to-person or zoonotic contagion occurs. The incidence of coccidioidomycosis is increasing in endemic areas, and it has been identified as the cause of as many as 17% to 29% of all cases of community-acquired pneumonia in some regions. Obtaining a travel history is recommended when evaluating patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis usually relies on enzyme immunoassay with immunodiffusion confirmation, but these tests may not be positive for one to three weeks after disease onset. Antifungal agents are not recommended for treatment unless the patient is at risk of or shows signs of complicated or disseminated infection. When antifungals are used, fluconazole and itraconazole are most commonly recommended, except during pregnancy. Treatment may continue for as long as three to 12 months, although lifetime treatment is indicated for patients with coccidioidal meningitis. Monitoring of complement fixation titers and chest radiography is recommended until patients stabilize and symptoms resolve. In patients who are treated with antifungals, complement fixation titers should be followed for at least two years. (Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(4):221–228. Copyright © 2020 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

Primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis, also known as valley fever, is an acute pulmonary infection that presents one to three weeks after a person inhales airborne spores of the fungus Coccidioides immitis or Coccidioides posadasii. These fungi normally grow in the soil, but when the soil is mechanically disturbed, airborne spores are released that can be inhaled and begin a parasitic existence in a human or animal host. Person-to-person or zoonotic contagion does not occur, and transplacental infection in humans has never been documented.1–3 There have been reports, however, of nonrespiratory spread via solid organ transplant or percutaneous transfer of infected fomites, but such cases are rare.4–7

Natural History

More than one-half of primary pulmonary Coccidioides infections are subclinical and resolve spontaneously.9 Infections generally impart lifelong immunity to reinfection and confer a positive delayed hypersensitivity skin test.10 Immunocompetent hosts usually overcome the acute infection without treatment but may form pulmonary granulomas containing dormant, noncontagious endospores that can potentially disseminate, particularly if the host later becomes immunocompromised.11–13 About 5% to 10% of infected people develop chronic pulmonary sequelae, such as nodules, cavitations, or chronic fibrocavitary pneumonia.14 In about 1% of cases, infection disseminates to bone, joints, or soft tissues within two years.9,14,15 Meningitis is a potential complication and is usually fatal if not treated appropriately.11,16

Epidemiology

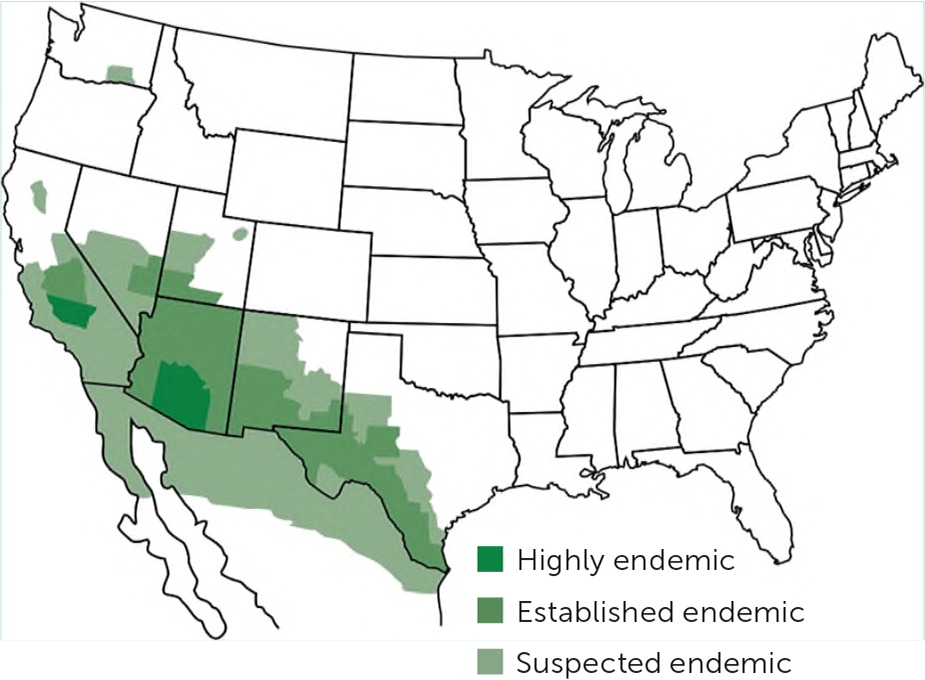

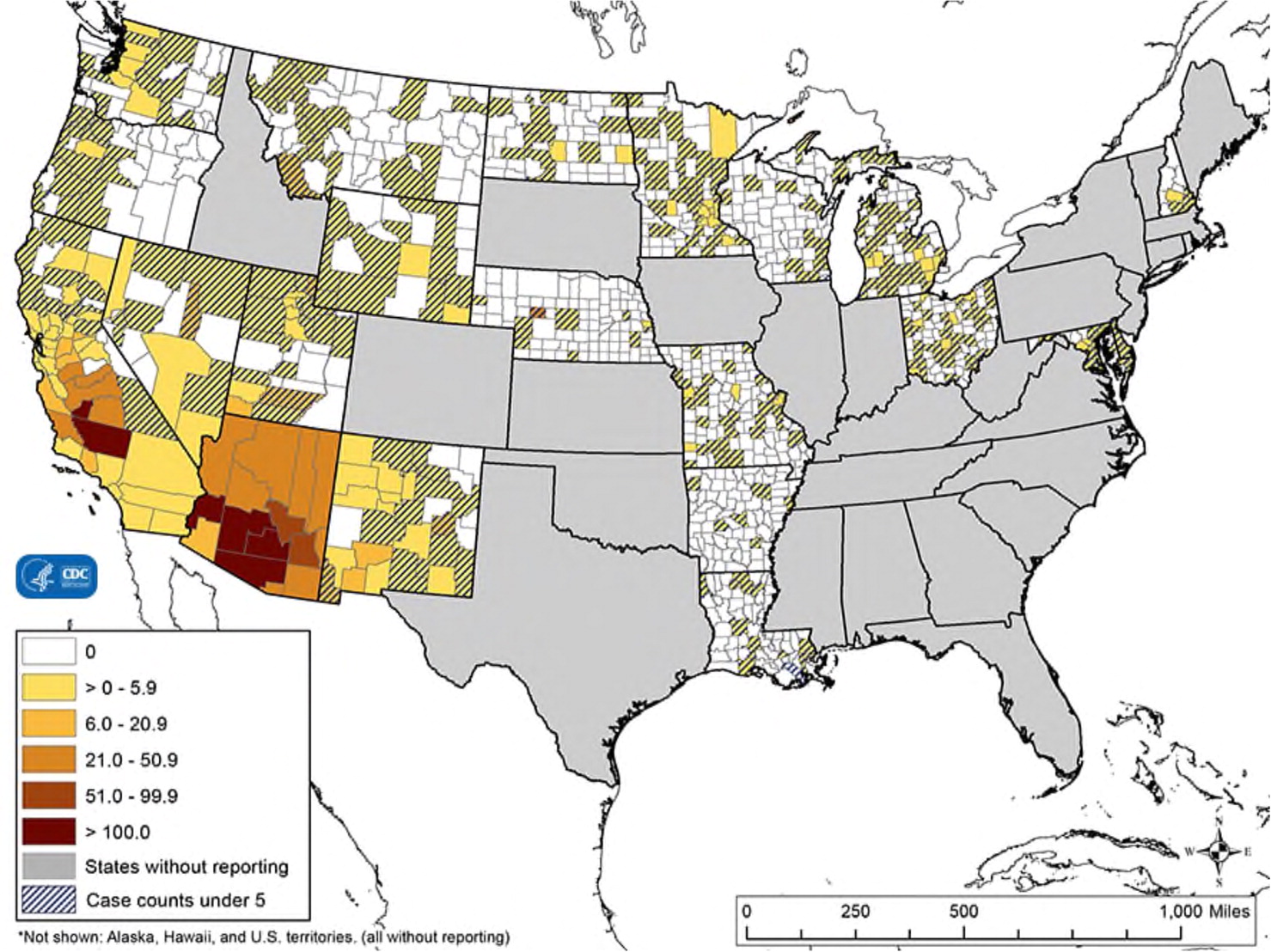

The incidence of coccidioidomycosis is increasing. From 1998 to 2011, the age-adjusted incidence in the endemic U.S. region increased by about 700% (from 5.3 to 42.6 cases per 100,000 people) because of factors such as weather, urban development, and changes in reporting methodology.1,17 The annual incidence in California more than tripled between 2014 and 2017 (from 6.0 to 18.8 cases per 100,000 people).18 The endemic range is also increasing and now includes areas in northeastern Utah, northern California, and south-central Washington.1,8 Data suggest that migration of infected wildlife is contributing to this expansion.19,20

Two studies conducted in 2000 to 2004 found that primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is a common cause of community-acquired pneumonia, accounting for 17% to 29% of cases in south-central Arizona during that time.21,22 Two-thirds of U.S. coccidioidomycosis cases occur in Arizona, and almost one-third occur in California.17 About 1% of cases present outside these endemic areas when infected travelers return home (Figure 28). Thus, family physicians throughout the country should be familiar with the evaluation and management of coccidioidomycosis.9,11,17,23

Primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis has a predilection for certain populations. Dusty outdoor activities within endemic areas, such as agriculture, construction, and archaeology, put participants at higher risk of infection. Some California correctional facilities have a disproportionate disease burden, although the reasons for this are not clear.24–26 People with deficiencies in cellular immunity are also at risk of disease dissemination, as are people with diabetes mellitus, older adults, blacks, and Filipinos.1,9,27,28 Women are particularly susceptible to complicated disease or dissemination during late pregnancy and in the immediate postpartum period.29

Clinical Presentation

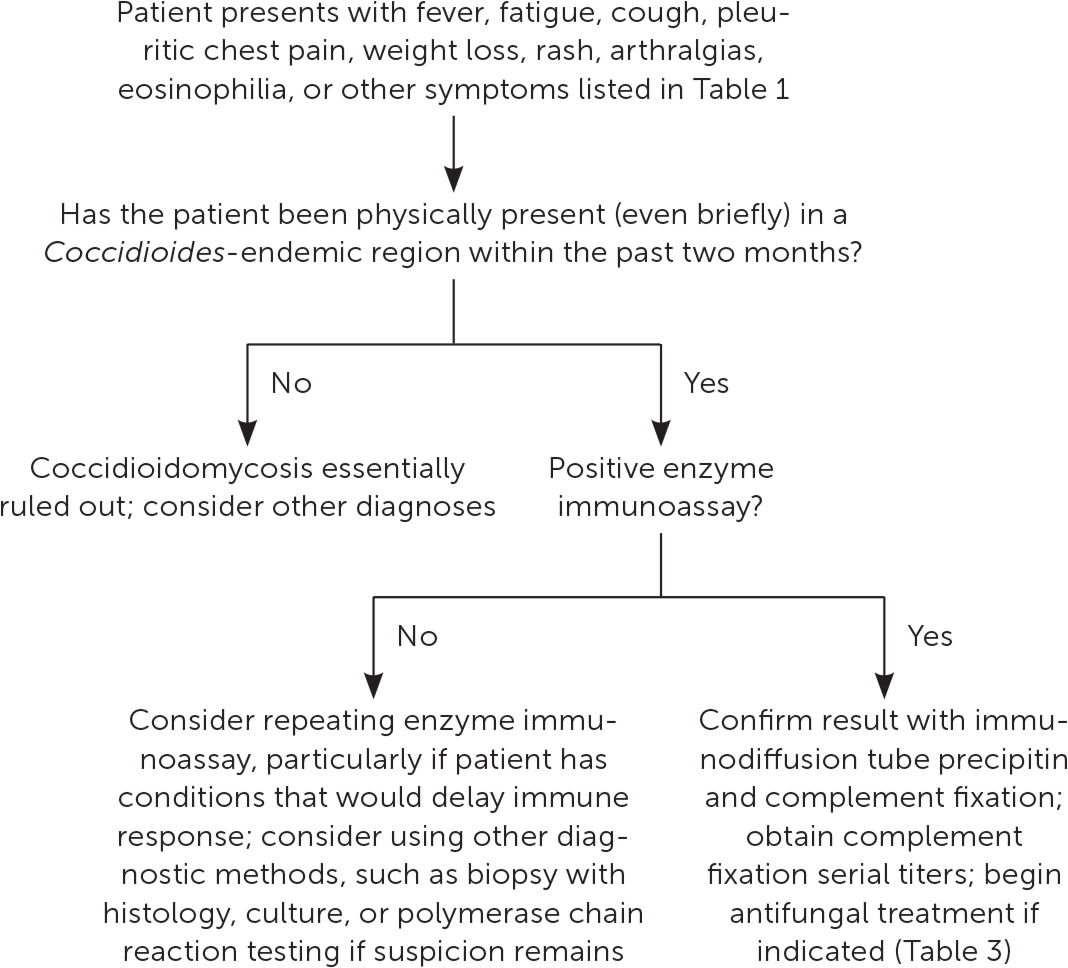

Primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis often goes unrecognized, and an estimated 60% to 80% of patients are initially treated with antibiotics before they are diagnosed with a fungal infection.8 The diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis should be considered in all patients presenting with community-acquired pneumonia if they live in or have traveled to an endemic area in the previous two months; the diagnosis can essentially be ruled out if the patient has no such travel history.9,30 A history of endemic travel accompanied by prolonged fever, lingering fatigue, weight loss, rash, arthralgias, or eosinophilia should also raise suspicion for coccidioidomycosis, or when usual testing offers no other plausible explanation for the patient’s symptoms.

SYMPTOMS

Primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis usually presents similarly to community-acquired pneumonia one to three weeks after exposure. It is occasionally associated with rheumatic symptoms. Common presentations are listed in Table 1 and include fatigue, cough, chest pain, headache, and fever, but symptoms are often diverse and nonspecific.8,15,31,32 Erythema nodosum, a manifestation of the patient’s immune response, is a nonspecific finding that indicates a favorable prognosis; its discovery can suggest the diagnosis.15,29,33

| Constitutional symptoms | Pulmonary symptoms |

|---|---|

| Arthralgias Erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, or a generalized exanthema Fatigue Fever Focal myalgia Headache Night sweats Weight loss | Cough Dyspnea Hemoptysis Pleuritic pain |

Diagnostic Approach

INITIAL STUDIES

On initial evaluation, the complete blood count is often normal, but eosinophilia greater than 5% should raise suspicion for coccidioidomycosis.25 The erythrocyte sedimentation rate may be mildly elevated.25,31 Chest radiography often appears normal but can show nonspecific findings such as pulmonary infiltrates, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, pneumothorax, or empyema.32,33 The differential diagnosis is shown in Table 2.9,35–37

| Condition | Differentiating characteristics and diagnostic tests |

|---|---|

| Bacterial | |

| Actinomycosis | Anaerobic culture from deep-needle or biopsy sample (which may require four weeks for growth); elevated CRP level and ESR; sulfur granules on tissue histology |

| Lung abscess | Blood, pleural fluid, or sputum culture; bronchoscopy with tissue histology; characteristic computed tomography or ultrasound findings |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection | Cold agglutinin titer > 1:16; enzyme immunoassay; mildly elevated hepatic transaminase levels or ESR; multiplex PCR respiratory panel; normal or mildly elevated white blood cell count; point-of-care serologic testing |

| Tuberculosis | Chest imaging; exudative pleural fluid showing normal or low glucose level, lymphocytic predominance, and elevated adenosine deaminase level; sputum analyses and culture; tuberculin skin testing or interferon-gamma release assay |

| Typical community-acquired pneumonia | Blood or sputum culture; chest imaging; multiplex PCR respiratory panel; travel history; urine antigen testing |

| Fungal | |

| Aspergillosis | Characteristic histology on tissue biopsy; chest imaging; elevated galactomannan level in bronchoalveolar lavage; elevated serum immunoglobulin E level; serology; sputum fungal culture |

| Blastomycosis | Blood or urine antigen testing; histology; sputum or bronchoscopy culture on specialized media (which may require four weeks for growth); travel history |

| Cryptococcosis | Association with HIV-infected or other immunocompromised hosts; blood, bronchoscopy, cerebrospinal, sputum, or urine fungal cultures; serologic and antigen testing |

| Histoplasmosis | Characteristic histopathologic findings on lung tissue or mediastinal lymph node biopsies; enzyme immunoassay on urine, blood, or bronchoalveolar lavage samples; fungal cultures; serologic testing; travel history |

| Paracoccidioidomycosis | Histology; serology; travel history |

| Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia | Association with HIV-infected or other immunocompromised hosts; PCR; respiratory histology; serum beta-D glucan assay |

| Sporotrichosis | Histopathologic findings of pyogenic granuloma; radiographic findings (may mimic tuberculosis); sputum culture |

| Neoplastic | |

| Lung cancer | Histology on any clinical sample |

| Lymphoma | Chest imaging; lymph node and/or bone marrow biopsy; peripheral blood analysis |

| Parasitic | |

| Loeffler syndrome | Larvae in respiratory secretions or gastric aspirate; peripheral eosinophilia |

| Paragonimiasis | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on serum sample; history of exposure to undercooked seafood; leukocytosis with eosinophilia; trematode ova in bronchoalveolar lavage, 24-hour sputum, stool, fine-needle aspiration, thoracoscopy, or transbronchial biopsy |

| Viral | |

| Influenza pneumonia | Antigen testing; chest imaging; multiplex PCR respiratory panel; reverse transcriptase–PCR; serology |

| Other | |

| Collagen-vascular lung disease | Assays for various autoantibodies |

| Eosinophilic pneumonia | Bronchoalveolar lavage cell count showing > 25% eosinophils; exposure and travel histories; lung biopsy |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis) | Abnormal findings on antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody testing, complete blood count, histology, or peripheral blood smear; elevated CRP level and ESR; hematuria |

| Sarcoidosis | Characteristic findings on pulmonary imaging; histopathology showing noncaseating granulomas Confirmatory tissue diagnosis should be obtained before administering glucocorticoids, which may trigger dissemination of an undiagnosed endemic mycosis |

CULTURE AND SEROLOGIC TESTING

Laboratory testing is required for a definitive diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis. The detection of Coccidioides in any clinical specimen by culture or microscopy is the diagnostic standard, but these results are not instantly available, and obtaining samples can be problematic.25 Therefore, the diagnosis is usually made serologically, although serologic results can be falsely negative while the immune response develops or in patients who are immunocompromised.25,38 Serologic results also may take several days to obtain.

Enzyme immunoassay is the most commonly used initial serologic test, and it is usually positive one to three weeks after disease onset.25 Immunodiffusion is also typically performed to confirm the diagnosis and allay concerns about false-positive results. 9,34,39,40 Immunodiffusion is more specific but less sensitive than enzyme immunoassay.9,11,34,41 Negative results may warrant retesting if suspicion for coccidioidomycosis remains.

OTHER TESTS

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing has proved clinically helpful in rapidly detecting elusive pathogens, and multiplex PCR respiratory panels are often used in the emergency department and hospital settings to detect respiratory pathogens. However, their use in coccidioidomycosis has been limited.42–46 Several sensitive and specific PCR assays have been developed to detect Coccidioides, and PCR testing is available at reference laboratories as an additional diagnostic option.8,25,46–48 Its effectiveness as a rapid initial diagnostic method for primary pulmonary coccidioidomycosis is currently being evaluated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.48

Management

UNCOMPLICATED CASES

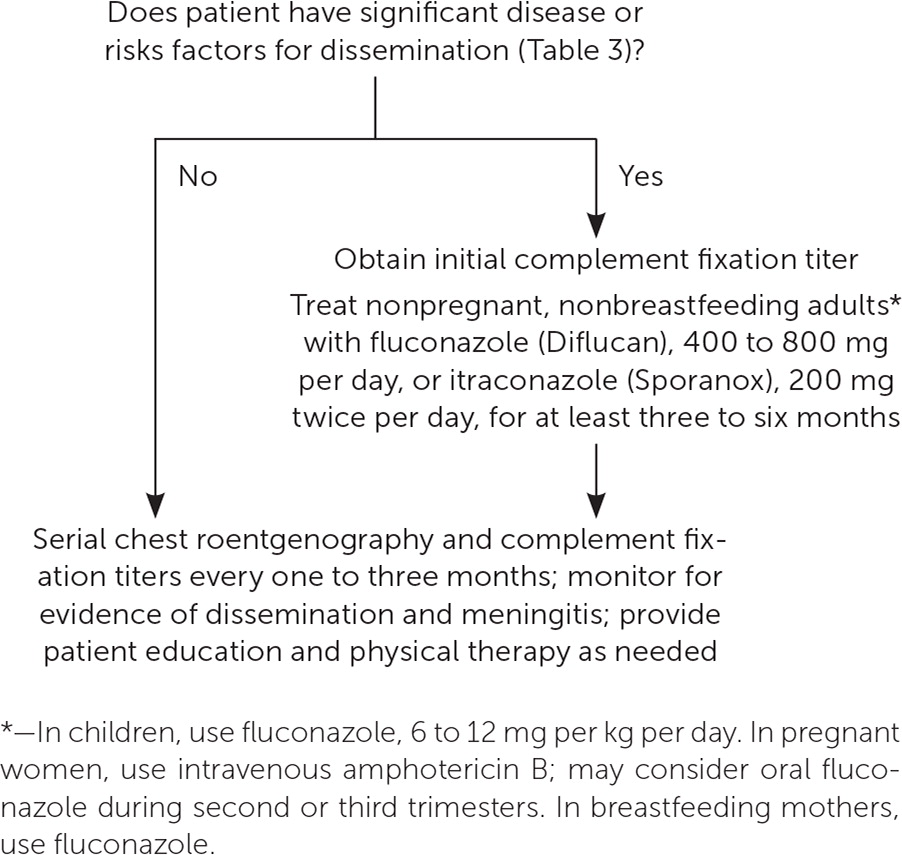

No prospective, randomized, double-blind trials have evaluated whether antifungal treatment improves outcomes in uncomplicated cases of coccidioidomycosis. Most untreated infections resolve without sequelae, so antifungal treatment is typically not recommended.9,49 However, patients should receive education and physical therapy as needed, and they should be monitored for chronic pulmonary residua or dissemination, which is clinically evidenced by unresolving respiratory symptoms or new focal symptoms such as skin lesions, joint pain, or unusual headache.9,30

Serial complement fixation titers should be obtained from the same laboratory every one to three months for one year or until they become negative.30,34 As a control, repeated testing of the original serum sample should be performed concurrently, and results should be compared with the newly tested serum. A titer that decreases over time is reassuring, whereas one that increases or is more than 1:32 raises concern for dissemination and a poor prognosis.9,25,32,36 Chest radiography is also typically repeated at intervals of one to three months for at least one year to document radiographic residua or resolution.9,30

ANTIFUNGAL TREATMENT

Antifungals are recommended for symptomatic patients who have clinically significant disease or an elevated risk of dissemination (Table 3).9,27–30,36,37,50,51 Nonpregnant, nonbreastfeeding adults are typically treated with oral fluconazole (Diflucan) or itraconazole (Sporanox).9 Children are usually treated with oral fluconazole.9 Pregnant women are normally treated with intravenous amphotericin B, although fluconazole can be considered during the second and third trimesters.9,29,36,37 Fluconazole—but not itraconazole—is recommended for breastfeeding women.9,29

| Manifestations of clinically significant disease |

| Anti-Coccidioides complement fixation antibody titers > 1:16 |

| Bilateral pulmonary infiltrates |

| Fever lasting more than one month |

| Hospitalization |

| Inability to work |

| Night sweats lasting longer than three weeks |

| Pulmonary infiltrates involving more than one-half of one lung |

| Symptoms lasting longer than two months |

| Weight loss > 10% |

| Risk factors for dissemination |

| Advanced age |

| Black race or Filipino ethnicity |

| Certain genetic mutations of immunity |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Hematologic malignancy |

| High-dose steroid therapy |

| Immunosuppressive chemotherapy |

| Inflammatory rheumatic disease |

| Lymphoma |

| Pregnancy and peripartum period |

| Thymectomy |

| Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor therapy |

| Uncontrolled HIV infection |

If antifungals are given, serial complement fixation titers should be monitored for at least two years because antifungal treatment has been associated with delayed dissemination.9,30,49 Antifungal therapy is often discontinued after three to 12 months if complement fixation titers stabilize, chest radiography shows stabilization, and symptoms resolve.9 Normal serologic results are not always required before discontinuing antifungal treatment in lower-risk patients.9

Pregnant women with a history of coccidioidomycosis should have complement fixation titers checked every six to 12 weeks to monitor for any elevation, which would suggest recrudescence.9,29 Serologic screening should be considered for all women in endemic areas at their first antenatal visit.29 Antifungal therapy should be considered if symptoms develop during pregnancy.9,30,36

SPECIAL SITUATIONS

Coccidioidal meningitis is a serious complication that presents insidiously.52 Unusual or frequent headaches, altered mental status, meningismus, nausea, vision changes, or vomiting in a patient with coccidioidomycosis warrants investigation. If coccidioidal meningitis is confirmed, lifelong antifungal therapy is indicated.9,52 Expert recommendations for less common clinical situations are available from the Infectious Diseases Society of America.9

Prevention

Preventive strategies for coccidioidomycosis are being explored. Data suggest that respirator use by construction workers in endemic areas may reduce disease risk.53 Prophylactic use of antifungals, although not generally recommended, is supported in specific clinical situations, such as organ transplant recipients.9,54 Despite a significant and ongoing effort, development of a vaccine for general use has not been successful.55

Data Sources: Essential Evidence Plus and PubMed searches in Clinical Queries were conducted and included combinations of the terms coccidioidomycosis, Coccidioides, valley fever, incidence, therapy, diagnosis, polymerase chain reaction, prognosis, natural history, prevention, and clinical decision rules. The search included prospective studies, statistical analyses, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and reviews. Also searched were websites of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, UpToDate, and Medscape. Further sources were drawn from the bibliographies of these articles. Search dates: October 2018 through August 2019.

The authors thank Jacinta Leyden, MD; McShirley Tran, PA-C; and Ngoc-Tuyen Tran, PA-C, for editorial assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.