Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(3):150-156

Related letter: Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Is Typically Not an Urgent Condition

Related letter: Long-Term Benefits of Manipulation for Neck Pain

Related letter: An Osteopathic Approach to Neck Pain

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Neck pain is a common presenting symptom in the primary care setting and causes significant disability. The broad differential diagnosis requires an efficient but global assessment; therefore, emphasis is typically placed on red flags that can assist in the early recognition and treatment of more concerning diagnoses, such as traumatic injuries, infection, malignancy, vascular emergencies, and other inflammatory conditions. The critical element in appropriate diagnosis and management of these conditions is an accurate patient history. Physical examination findings complement and refine diagnostic cues from the history but often lack the specificity to be of value independently. Diagnostic tools such as imaging and electrodiagnostic tests have variable utility, especially in chronic or degenerative conditions. Treatment of mechanical or nonneuropathic neck pain includes short-term use of medications and possibly injections. However, long-term data for these interventions are limited. Acupuncture and other complementary and alternative therapies may be helpful in some cases. Advanced imaging and surgical evaluation may be warranted for patients with worsening neurologic function or persistent pain.

Neck pain is a common presenting symptom in primary care, with an incidence of 10.4% to 21.3% per year.1 It is the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide.1 The prevalence of neck pain is higher in older adults because of degenerative changes in facet joints and the collapse of intervertebral disks.2 It is estimated that only one in five people with neck pain seeks medical care.3 The differential diagnosis is broad and includes common conditions such as muscular strains and arthritis, as well as more dire conditions such as fractures, spinal cord and nerve injuries, neoplastic disorders, infections, and inflammatory conditions. Family physicians must be able to recognize when neck pain signals a potentially serious condition and should be able to generate an accurate diagnosis through findings from the patient's history, physical examination, and appropriate testing.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Myelopathic signs and symptoms such as lower extremity weakness, balance problems, and bowel and bladder irregularities should be evaluated and treated urgently.5 | C | Expert consensus |

| Patients with neck pain should be assessed for comorbidities because underlying inflammatory or rheumatologic conditions increase the risk of cervical spine injury.6,8 | C | Consensus, usual practice, expert opinion, disease-oriented evidence, and case series |

| Electrodiagnostic studies should not be used routinely in the evaluation of isolated neck pain without peripheral neuropathic symptoms.20 | C | Consensus guideline, expert opinion, and disease-oriented evidence |

| Narcotic pain medications have no benefit for cervical pain and should be used with caution.26 | B | Systematic review |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not do nerve conduction studies without also doing a needle electromyogram for testing for radiculopathy, a pinched nerve in the neck or back. | American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic Medicine |

Focused History

Obtaining an accurate clinical history is critical in the initial evaluation of neck pain. Acute vs. chronic timing of symptoms and the presence of neuropathic vs. nonneuropathic symptoms can help determine the urgency of the evaluation.

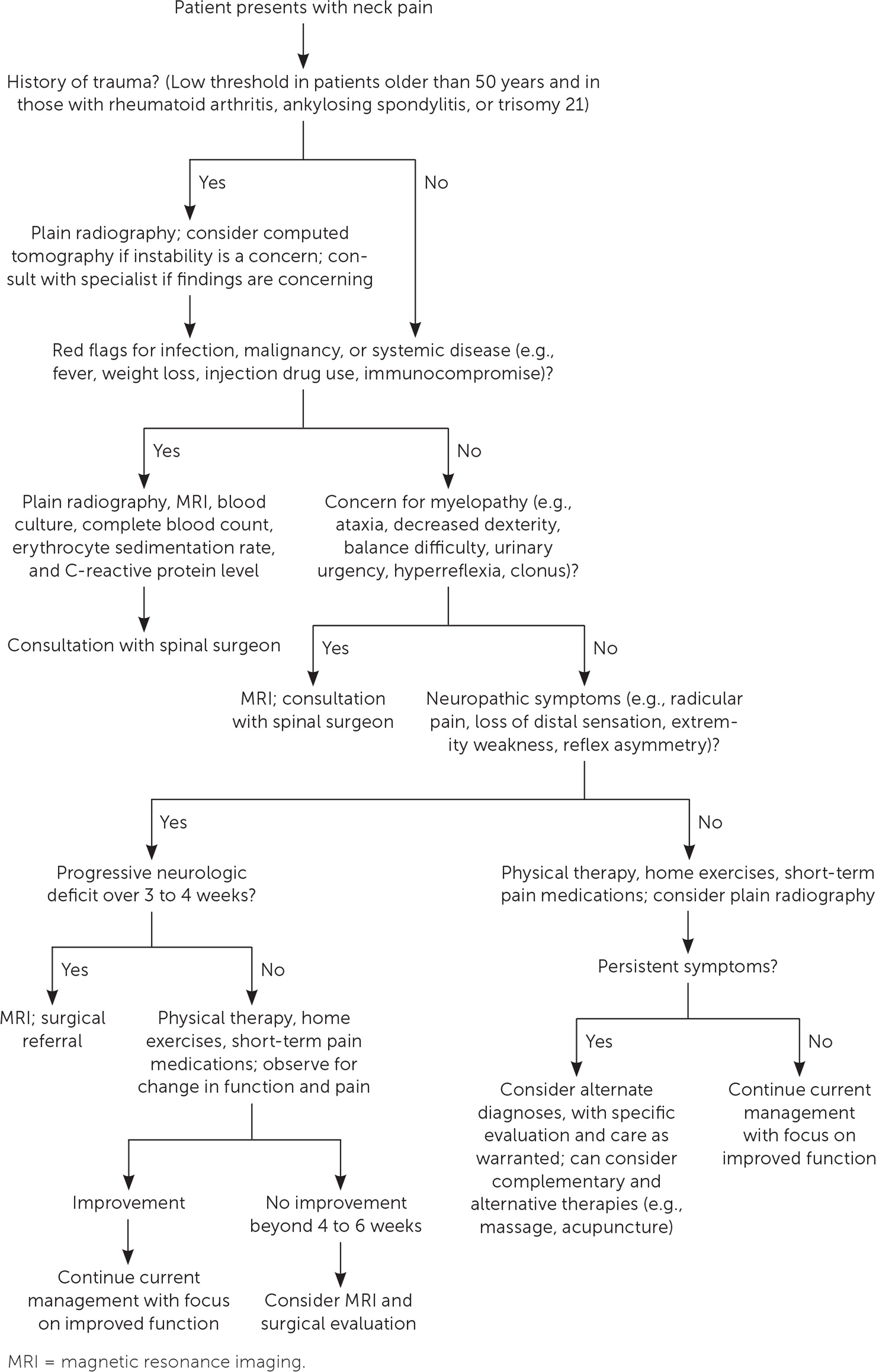

When evaluating a patient with neck pain, the physician must be alert for red flags in the history and physical examination that may indicate the need for urgent testing and intervention. Similar to guidelines for the evaluation of lower back pain, a systematic approach that maintains vigilance for severe pathology in the neck is recommended.4 Table 1 summarizes some of the more serious diagnoses and their associated clinical findings, as well as recommended diagnostic tests. Figure 1 is a recommended approach to patients with neck pain. This article does not focus on acute traumatic injuries or vascular emergencies, but these elements warrant consideration based on the presentation.

| Condition | Historical findings | Physical examination findings | Next steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection (e.g., diskitis, epidural abscess, herpes zoster, meningitis, osteomyelitis) | Fever, meningism, night sweats, photophobia | Kernig sign, nuchal rigidity, photophobia | Antibiotics, CRP, ESR, lumbar puncture, MRI with or without contrast, white blood cell count |

| Inflammatory condition (e.g., ankylosing spondylitis, polymyalgia rheumatica, rheumatoid arthritis) | Generalized joint pain, morning stiffness that improves with exercise | Other joints affected | CRP, ESR, radiography, rheumatoid factor testing |

| Malignancy (e.g., chordoma, metastasis, multiple myeloma, spinal cord tumor) | Anorexia, fever, history of malignancy, intractable night pain, pain not relieved at rest, weight loss | Significant bony tenderness, other signs similar to myelopathy | MRI |

| Myelopathy (e.g., amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cervical cord compression, transverse myelitis) | Ataxia, bowel and bladder dysfunction, deep aching neck pain, gait changes, tremor, possible radicular symptoms or weakness | Babinski reflex, clonus, fasciculations, Hoffmann sign, hyperreflexia, increased muscle tone, Lhermitte sign | Electromyelography, MRI, urgent neurosurgical consultation |

| Thoracic outlet syndrome | Intermittent paresthesias, pain worsened by use, unilateral symptoms; may be confused with cervical radiculopathy | Positive Roos test, tenderness to palpation over distal arm veins or at insertion of pectoralis minor | MRI or ultrasonography (duplex or arterial) |

| Vascular emergency (e.g., arterial dissection, vertebrobasilar insufficiency) | Ripping or tearing sensation in neck, diplopia, drop attacks, headache, syncope, transient ischemic attack symptoms, vertigo, vision changes | Kernig sign, unilateral decrease in sensation, unilateral weakness | Urgent referral and imaging (CT or CT angiography) |

Rapidly progressive neuropathic symptoms warrant more aggressive evaluation. Injury to the central spinal cord or nerve roots may be the result of degenerative changes, trauma, mass effect, infection, or other inflammatory or demyelinating conditions. Even without an acute presentation, physicians should be mindful of myelopathic signs and symptoms.4 Myelopathy refers to neurologic compromise resulting from a disturbance of spinal cord tracts within the spinal canal. Initial symptoms include deep, aching neck pain with possible radicular symptoms and muscle weakness; these can quickly progress to gait changes, ataxia, and bowel and bladder dysfunction.5 Physical examination findings associated with a myelopathic disease process include increased muscle tone, fasciculation, clonus, hyperreflexia, the Babinski reflex, and the Lhermitte and Hoffmann signs.

Concurrent systemic symptoms of fever, fatigue, or rash could indicate an infectious etiology. These symptoms in a patient with neck stiffness, photophobia, or other focal neuropathic findings should raise concern for meningitis, epidural abscess, or diskitis (i.e., a bacterial infection of the intervertebral disk tissue). Similarly, neck pain in the setting of described or observed weight loss, significant lymphadenopathy, unexplained fever, or fatigue may signal malignancy or an underlying inflammatory condition.

Certain comorbid disorders and patient factors increase the risk of cervical spine conditions (Table 2). Cervical spine pathology is present in more than one-half of patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and the long-term risk of severe pathology in these patients is higher than in unaffected people.6 Individuals with trisomy 21 are at risk of atlanto-occipital instability, which should prompt concern for complications of even mild trauma, as well as for advanced or premature degenerative changes.7 Ankylosing spondylitis can cause neck stiffness and pain. Patients with this condition also have an increased risk of complications from mild trauma.8 Numerous other processes and conditions can be considered in the differential of neck pain, including herpes zoster, angina, endocrine and compressive tumors, fibromyalgia, and psychogenic pain. Many of these conditions can overlap and be part of multifactorial presentations. One study estimated that 43% of neck pain cases are nonneuropathic, 7% are neuropathic, and 50% are mixed.9

| Condition/patient factor | Potential pathology |

|---|---|

| Age > 50 years | Degenerative changes that narrow the spinal canal, potentially leading to myelopathy |

| Chronic inflammation, Marfan syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis | Frailty fracture |

| Diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, injection drug use, kidney failure, liver failure, long-term steroid use | Infection |

| Previous or current malignancy | Spinal metastasis vs. primary malignancy |

| Previous trauma | Bony or ligamentous disruption, whiplash-associated disorder |

| Trisomy 21 | Subluxation from atlantoaxial ligament laxity |

The remainder of the patient history should focus on specific descriptions of any injury, including potential mechanism, inciting and relieving factors, and pain patterns throughout the day.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should target concerns revealed in the history and distinguish between mechanical and neuropathic symptoms. Localized bony tenderness or prominence is an indication for imaging, whereas soft tissue tenderness may represent myofascial pain, infection, or lymphadenopathy. Although range of motion measurements are widely referenced, their diagnostic relevance is limited and nonspecific.10,11 Range of motion can be more useful in identifying asymmetry or provocation of local or radiating symptoms (e.g., shooting pain down the spine with neck flexion or extension).

| Test | Description | Clinical relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Babinski reflex | Dorsiflexion of the big toe when the plantar aspect of the foot is stimulated with the blunt end of a reflex hammer (typically lateral to medial from heel to metatarsal) | Limited stand-alone value, but can be more specific when evaluating compressive upper motor neuron conditions (e.g., myelopathy) |

| Hoffmann sign | Thumb adduction and flexion at the distal phalanx with possible finger flexion after flicking the distal tip of the third or fourth finger | Upper motor neuron test; has low positive predictive value for localizing spinal vs. brain lesions |

| Lhermitte sign | Electric shock sensation down the spine or into the limbs with neck flexion or extension | Suggests nonspecific central cord compression or provocation; can be positive in patients with cervical myelopathy, multiple sclerosis, intraspinal masses, or certain acute infections |

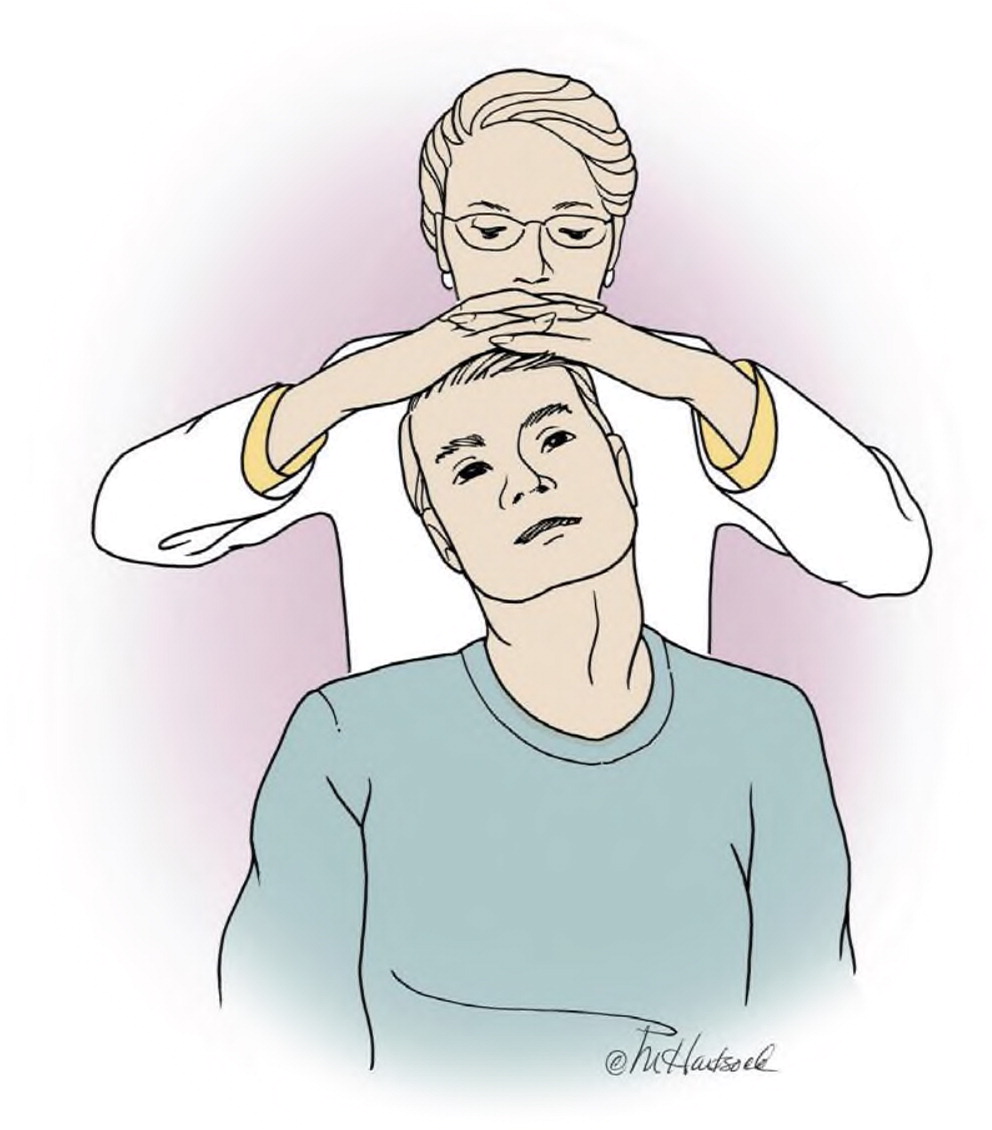

| Spurling test (Figure 2) | Passively move the patient's neck into lateral flexion and extension, then apply gentle downward axial compression; a positive result is pain radiating to the upper limb ipsilateral to the rotation position | Well-established specificity and sensitivity for cervical radiculopathy |

| Upper limb tension test (Figure 3) | With patient supine and the shoulder in a neutral position with the elbow flexed, depress the shoulder, abduct it to 90 degrees, extend the elbow and fingers, then extend and supinate the wrist while the patient flexes the neck to the contralateral and then ipsilateral sides; a positive result is reproduction of pain at any step | Highest sensitivity for cervical radiculopathy; recommended for combined use with the Spurling test in patients with suspected cervical radiculopathy |

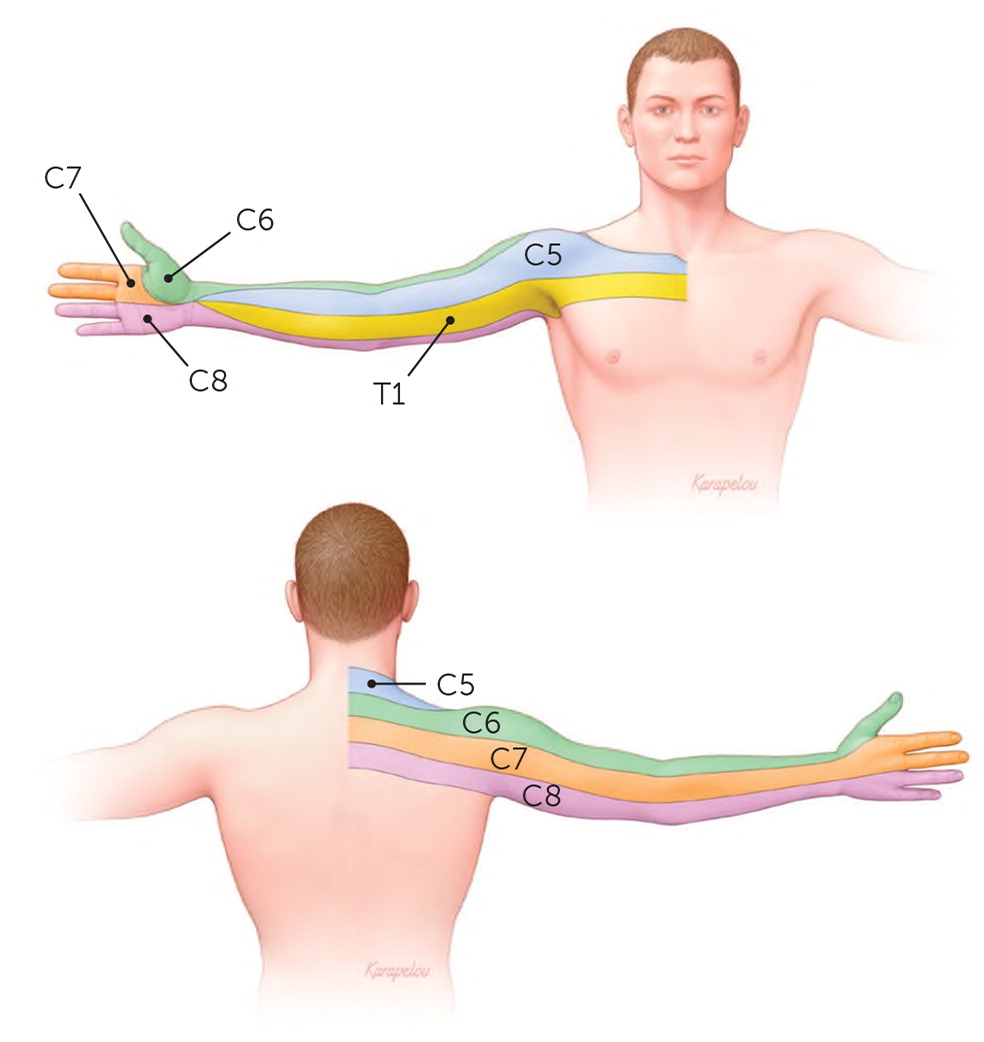

Further examination should include upper and lower extremity strength and deep tendon reflexes if neuropathic conditions are suspected. Radiculopathy is manifested by dermatomal-based upper extremity pain (Figure 412), changes in sensation, and weakness. In contrast, myelopathy at similar levels in the neck can provoke less overt lower extremity findings, such as balance difficulties, spasticity, and weakness. Examination may reveal atrophy of the hands, hyperreflexia, and the Lhermitte sign.5

Imaging and Other Diagnostic Tests

The American College of Radiology recommends plain radiography as the initial imaging modality in patients with new or increasing nontraumatic neck pain who do not have red flag symptoms.17 Validated clinical tools such as the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study criteria and the Canadian C-Spine Rule can help determine when radiography may be helpful.17,18 Immediate radiography does not improve patient-oriented outcomes in those who do not have recent trauma or red flag symptoms.18 In addition, imaging can detect abnormalities even in asymptomatic patients; for example, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) detects degenerative cervical disks in 15% of asymptomatic patients in their 20s, increasing to more than 85% of asymptomatic patients older than 65.19

The time to diagnosis and intervention can be critical when serious conditions are suspected. MRI is recommended for patients with suspected infection, overt neurologic compromise, or progressive neurologic symptoms; it may be appropriate for patients with moderate to severe neck pain that lasts longer than six weeks and does not resolve with standard treatment.20 Computed tomography may be useful in trauma cases, when bony disruption is suspected, or when MRI is contraindicated.

Electromyography and nerve conduction studies are not recommended for patients with neck pain unless they also have numbness, weakness, or pain in the arms or legs. There is insufficient evidence for electrodiagnostic testing, even in cases of suspected radiculopathy.20 Electromyography may be useful when peripheral neuropathy of the upper extremity is a suspected alternative diagnosis.20

Treatment Principles

In the absence of red flag findings that require urgent care, treatment can generally focus on the patient's level of pain and function. Many patients will improve over time, regardless of treatment or whether the cause is neuropathic or nonneuropathic. For example, most patients with cervical radiculopathy will improve with nonsurgical care: 80% to 90% have significantly improved pain and resolution of weakness or reflex deficits within four weeks.21,22

Conservative care for patients with neck pain often includes medications for pain relief. Although practice patterns may prompt the use of specific agents, there is little evidence to support the long-term use of these medications in most patients with neck pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and oral muscle relaxants are commonly recommended for patients with nonneuropathic pain. Data on the effectiveness of these medications for neck pain are limited; however, these agents are not effective for similar musculoskeletal conditions, such as low back pain.23 Although there is some evidence that oral corticosteroids provide short-term pain relief in patients with acute radiculopathy,24 there is little evidence that any medication affects recovery. Tramadol may have some benefit, but only in the short term.25 Narcotics can provide modest short-term pain relief, but there is no evidence of sustained benefit, and the risks of cognitive impairment and abuse limit their use.26 Inflammatory conditions may briefly respond to steroids or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, but there is minimal evidence that these medications provide lasting benefit in degenerative conditions, despite their widespread use.4 Similarly, injections of anesthetics, corticosteroids, or botulinum toxin have shown little or no long-term benefit in acute or chronic neck pain.27,28 There is limited evidence for the short-term use (one to two months) of radiofrequency ablation in patients with persistent cervical pain.29

Given the broad range of potential neck pain etiologies and the variety of complementary and alternative treatment options, it is challenging to determine the value of these treatments for neck pain. They generally provide modest benefit compared with medication alone or no therapy.30 Acupuncture has modest benefit in patients with mechanical neck pain.31 Isolated manipulation and mobilization may provide temporary pain relief but not consistent long-term benefit.32 Treatments such as dry needling, low-level laser therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, and compression therapy have some potential for short-term pain relief, but no reliable long-term data exist to offer specific guidance for these options.33,34

Surgical referral is warranted in cases of progressive neurologic deficit. For persistent but nonprogressive cases, appropriate thresholds and timing for referral are unclear. There is some evidence to support surgical referral after four to eight weeks of ongoing pain, but long-term data are limited.35

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term neck pain in combination with the following varied strings: diagnosis, evaluation, and differential diagnosis. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports, the Cochrane database, DynaMed, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: May 1 and July 18, 2019, and May 16, 2020.