Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(7):411-417

Related letter: Oral and Dental Injury Prevention in Children and Adolescents

Patient information: See related handout on preventing accidental injuries in children, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Unintentional injury accounts for one-third of deaths in children and adolescents each year, primarily from motor vehicle crashes. Children younger than 13 years should be restrained in the back seat, and infants and toddlers should remain rear-facing until at least two years of age. Infants should be positioned on their backs in a crib, on a mattress with only a fitted sheet to avoid suffocation, and all items that could potentially entrap or entangle the child should be removed from the sleep environment. Fencing that isolates swimming pools from the house is effective in preventing drownings. Swimming lessons are recommended for all children by four years of age. Inducing vomiting after toxic ingestions is not recommended. Installing and maintaining smoke detectors, having a home escape plan, and teaching children how to respond during a fire are effective strategies for preventing fire-related injuries or death. The most effective way to prevent gun-related injuries in children and adolescents is the absence of guns from homes and communities. Family physicians should counsel patients with guns in the home to keep them locked, unloaded, and with ammunition stored in a separate locked location. Fall injuries can be reduced by avoiding walkers for infants and toddlers. Consistent helmet use while bicycling reduces head and brain injuries. Although direct counseling by physicians seems to improve some parental safety behaviors, its effect on reducing childhood injuries is unclear. Community-based interventions can be effective in high-risk populations.

Unintentional injury is the leading cause of death in children and adolescents one to 19 years of age, accounting for about one-third of deaths in this population each year.1 Motor vehicle crashes are the most common cause of fatal injuries, followed by drowning and poisoning. Unintentional injury is the fifth leading cause of death in children younger than one year; 85% of these deaths are due to suffocation.1 Boys are nearly twice as likely as girls to have fatal injuries,1 and there are also significant racial disparities. In 2017, Black and American Indian/Alaska Native children were 1.7 and 1.4 times, respectively, more likely than White children to die from unintentional injury, whereas Asian/Pacific Islander children were about half as likely as White children to have a fatal unintentional injury.1 Nonfatal injuries account for significant morbidity among children, with falls being the most common, followed by contact injuries (i.e., being struck by or against an object).1 Physicians have a pivotal role in preventing unintentional injuries in children. There are many evidence-based strategies that, when implemented, are proven to reduce morbidity and mortality from injuries (Table 1).2–13

| Cause of injury | High-risk groups | Prevention strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Bicycling | All children | Helmets should be worn at all times2 |

| Bicycles should be checked regularly for brake malfunction or loose parts | ||

| Drowning | All children | Pool fences should completely enclose and isolate the pool from the home3 |

| Swimming lessons are recommended for all children by four years of age and may be considered as early as one year of age4 | ||

| All adults and caregivers should be trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation5 | ||

| Coast Guard–approved life jackets should be worn at all times while boating5 | ||

| Falls | Infants and toddlers | Children should be taught not to climb on objects6 |

| Infant or toddler walkers should not be used7 | ||

| Safety gates should be used, and stairs should be carpeted8 | ||

| Fires | Children younger than five years | Smoke detectors should be installed and maintained regularly9 |

| Families should have a fire escape plan and conduct home fire drills9 | ||

| Smoking should not be allowed in the home9 | ||

| A fire extinguisher should be kept in the home9 | ||

| Guns | Toddlers and teenagers | Guns should be stored unloaded and in locked locations, with ammunition in a separate locked location10 |

| Motor vehicle crashes | All children | Children should be restrained with age- and size-appropriate restraints and remain rear-facing until at least two years of age11 |

| Children younger than 13 years should ride in the back seat of the vehicle11 | ||

| Poisoning | Toddlers and teenagers | Poison control or emergency services should be called for any potential ingestion or exposure12 |

| Vomiting should not be induced (including with syrup of ipecac) if a potential ingestion is suspected12 | ||

| Suffocation and strangulation | Infants | Infants should sleep on their backs in a crib13 |

| Infants should sleep on a mattress with a fitted sheet and no additional bedding or toys13 | ||

| Infants should sleep in the same room as a caregiver for the first six to 12 months of life13 |

Motor Vehicle Crashes and Pedestrian Injuries

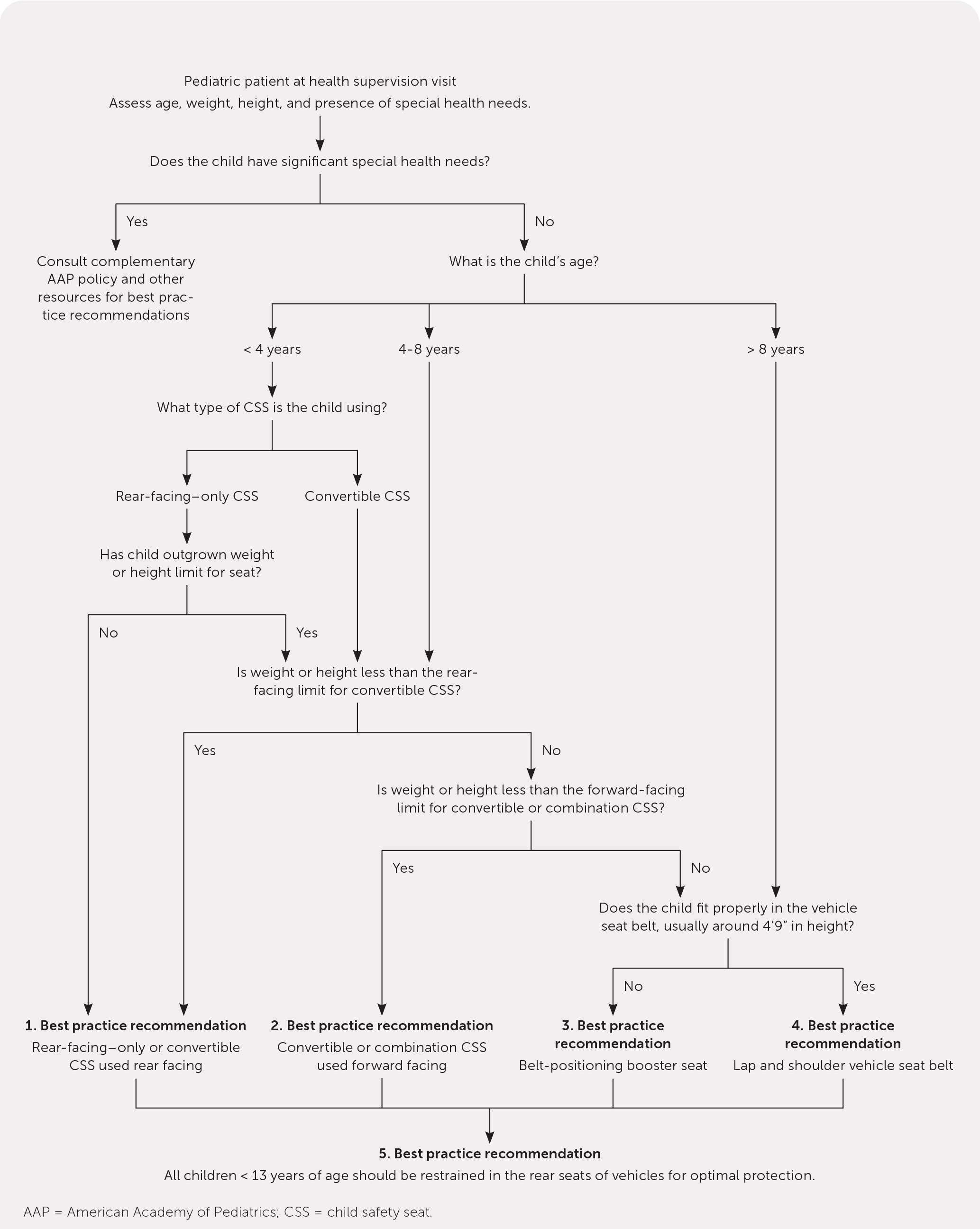

Motor vehicle crashes account for nearly 50% of all fatal injuries in children and adolescents.1 In the United States, an average of three children 14 years or younger are killed in traffic-related crashes each day.14 Child safety seats reduce mortality from motor vehicle crashes by 71% in infants younger than one year, 54% in children one to four years of age, and 45% in those five years and older.14 Figure 1 is an algorithm to guide implementation of child safety seat recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) based on the child's age, height, and weight.11 Infants and toddlers should ride in a rear-facing seat for as long as the seat's manufacturer specifies, generally until at least 24 months of age.11 Children younger than 13 years should be properly restrained in the back seat.11 Unrestrained children are at much greater risk of death in a crash. Compliance with proper child safety restraints is reported to be 90%; however, 35% of children 12 years and younger who were killed in motor vehicle crashes in 2017 were unrestrained.14 Newborns born at or before 37 weeks' gestation should be directly observed in their car seat for 90 to 120 minutes before hospital discharge.15 The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration's website allows caregivers to register car seats so that they receive safety updates, as well as resources for safety technicians (including Spanish speakers) to evaluate for proper car seat installation (https://www.nhtsa.gov/equipment/car-seats-and-booster-seats).

Distracted driving is another significant cause of traffic-related injury. The risk of a crash or near-crash is increased in novice drivers (16 to 17 years of age) who are dialing a cell phone, sending or receiving text messages, or reaching for a phone or other object.16 Nearly 50% of teenagers report that they have texted while driving, and those who have are less likely to wear a seat belt and more likely to drink and drive or ride with a driver who has consumed alcohol.17 States with strict alcohol laws have lower rates of motor vehicle– related fatalities in children.18 The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) recommends counseling teenagers about distracted driving during all preventive health care visits.19

The incidence of pedestrian injury is significantly higher in children vs. adults, and those who live in low-income urban areas are at greatest risk.20 The Safe Routes to School program allocates federal funds for improved sidewalks, signage, safe crossings, and bicycle lanes throughout the United States; one study found that this program reduced pedestrian injuries by 44% during school-travel hours in New York City.21

Suffocation and Strangulation

The infant mortality rate from accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed (ASSB) has increased significantly in recent decades, from an average of 12.4 deaths per 100,000 infants in 1999 to 28.3 per 100,000 infants in 2015.22 Although the reason for this increase is unclear, it is thought that the use of unsafe products and improved differentiation between ASSB and sudden infant death syndrome may have contributed.22 Sudden infant death syndrome is death that is unexplained after a thorough investigation; however, there are no universally accepted definitions for what autopsy findings define death from ASSB.23 The most common cause of suffocation is soft bedding, followed by overlay (i.e., caregiver rolls onto infant during sleep) and wedging of a child between the bed and mattress.24 Nearly 50% of suffocation deaths involving soft bedding occurred in an adult bed.24 The AAP recommends that infants sleep on their backs, in their own crib, on a mattress with only a fitted sheet, and in the same room as a caregiver for the first six to 12 months of life.13 Additional bedding (e.g., pillows, nonfitted sheets), toys, and stuffed animals should be kept away from the sleep area, and the mattress should fit into the crib without a gap.13 One study showed that only 55% of caregivers reported receiving correct advice about safe sleep during health care visits, and 20% reported receiving no advice at all.25 Counseling about prevention of ASSB should occur at every visit during the first year of a child's life.

Drowning

Drowning is the second leading cause of death in children and adolescents one to 19 years of age.1 Black children have the highest rates of death from drowning, followed by American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic children.1 One study found that nearly 60% of Black and Hispanic children cannot swim or are not comfortable swimming, compared with 30% of White children.26 Barriers to swimming proficiency may include cultural factors, discriminatory experiences, and lack of access to affordable swimming lessons and places to swim.27 The AAP recommends that all children receive swimming lessons by four years of age and that parents consider lessons as early as one year of age based on an individualized evaluation of the child's physical and emotional capacity and exposure to water.4 A recent cohort analysis showed that bystander training in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) significantly improved neurologically favorable survival after cardiac arrest from drowning.28 The AAFP recommends that all adults and caregivers be trained in CPR.5 A Cochrane review found that pool fences significantly reduce the risk of drowning, and fences without direct access to the home are preferred.3 While boating, all passengers should wear Coast Guard–approved life jackets at all times.5 Physicians are encouraged to screen for swimming ability in children and connect those in need with community resources.

Poisoning

U.S. poison control centers receive more than 1 million calls each year regarding potential exposures in children.29 The most commonly ingested substances include medications, cleaning products, and personal care products.29 Opiates and benzodiazepines are the most common prescription medications ingested by children younger than six years, and 27% of these ingestions result in hospitalization.30 Poison control centers managed more than 5,000 cases of exposure to electronic cigarette devices and liquid nicotine in 2019.31 Since marijuana was legalized in Colorado in 2014, calls to state poison control centers regarding marijuana exposure in children younger than eight years more than doubled.32 Accidental poisonings can be prevented by keeping potential poisons out of children's reach, not transferring medications to an alternate container, not referring to medicine as candy, and ensuring appropriate disposal of all unused medications.12 If a potential ingestion is suspected, the item should be taken away from the child, and the caregiver should have the child spit out any substance remaining in the mouth. Inducing vomiting with or without use of ipecac is not recommended.12 A poison control center or emergency services should be called immediately. Contact information for poison control centers should be provided during well-child examinations.

Fires

Residential fires are the most common cause of fire-related mortality in children, and more than one-half of these fires result from cooking.33 Absence of smoke detectors is a significant risk factor for fire-related death, as are impairment from alcohol use and fires that occur in mobile homes.34 Community-delivered fire prevention education is effective in preventing fires35; recommendations from the AAP include keeping a fire extinguisher in the home, installing smoke detectors in all bedrooms and rooms with furnaces, conducting home fire drills, having a fire escape plan, and not smoking in the home.9

Guns

In 2017, a total of 117 children died of gun-related injuries.1 Although an estimated 29% of gun-related injuries are unintentional,1 assault is the most common reason for these injuries.36 Children younger than four years and teenagers 15 to 19 years of age are the most likely age groups among children to be killed unintentionally by guns. The AAP states that the most effective way to prevent unintentional gun-related injuries in children and adolescents is to keep guns out of their homes and communities.37 Strategies recommended by the AAFP include safe storage of guns, screening for intimate partner violence, and screening for and treating depression.38 A 2016 systematic review showed that when laws were implemented restricting the purchase of and access to guns, unintentional gun-related deaths in children declined.39 Similar decreases in fatal shootings occurred when safe storage laws were enacted.40 Regardless of the laws in place, separation and locked storage of guns and ammunition have been independently shown to reduce gun injuries in children.10 Physicians should ask patients whether there are guns in the home and counsel them about the risk of gun-related injury and about safe storage practices. Finally, physicians should consider contacting legislators if local gun laws are not in the best interest of children's safety.41

Falls

Falls are the leading cause of unintentional injury in children, although these injuries are less likely to be fatal.1 Approximately 5,000 falls occur from windows (usually from the first three floors) each year.42 Interventions associated with a protective effect include the use of safety gates and carpeted stairs, and teaching children not to climb on objects.6,8 Falls are more likely when children's diapers are changed on a raised surface, when their car seat or bouncer is set on a raised surface, and when walkers are used.6,7

Bicycle, Skateboard, and Scooter Injuries

A 2016 systematic review showed that rural location, lower socioeconomic status, and sidewalk riding are significant risk factors for bicycle-related injuries.43 A Cochrane review showed that helmets reduce the risk of bicycle-related head and brain injuries by 63% to 88% in people of all ages.2 Mandatory helmet-use laws significantly decrease rates of bicycle-related head injury.44 Neither the type of bicycle nor whether the child rides with a companion is associated with injury risk.43 Bicycles should be checked frequently for brake malfunction or loose parts.

The most common injuries associated with skateboarding and motorized scooters are arm fractures and head injury, respectively.45,46 Wearing wrist and elbow pads significantly reduces the risk of skateboarding injury. The AAFP recommends consistent helmet use as well as appropriate helmet legislation.47

Effectiveness of Counseling and Intervention

Anticipatory guidance from family physicians is a fundamental part of the well-child examination. Physicians are uniquely positioned to advocate for their patients regarding access to community resources and legislation to improve childhood safety. In a review of national injury data, only 15% of children presenting with injuries were counseled about prevention before the incident.48 There is evidence that office-based counseling increases adherence to recommendations, specifically those related to fire safety, fall prevention, and motor vehicle safety.49 However, more evidence is needed to determine whether counseling reduces overall injury rates. A Cochrane review showed that when parent training programs were implemented, childhood injury rates decreased, specifically in populations with lower socioeconomic status.50 There has been an effort to use new technology such as computer kiosks and smart-phone apps in health care settings to deliver childhood injury–prevention information.51 The use of innovative tools and efforts to connect patients in need with community resources should be considered during all well-child visits to lessen the significant burden that unintentional injury poses to children.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Theurer and Bhavsar,52 and by Schnitzer.53

Data Sources: The Cochrane database was searched using the term injury prevention with the terms child, infant, and adolescent. Policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians were reviewed. A Google Scholar search was performed using the terms child, infant, and adolescent in combination with the terms accident prevention, poisoning, falls, injury prevention, burns, fire safety, motor vehicle crash prevention, helmets, unintentional gun, drowning, suffocation, sudden infant death syndrome, gun violence, bicycling, and accidental falls. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, guidelines, case studies, policy statements, mortality data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and recommendation statements from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Search dates: November 15, 2019, to July 19, 2020.